Home | Category: Art and Architecture

GLASS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

glass and bronze grapes

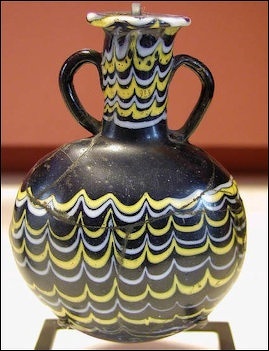

Glassmaking was known in ancient Egypt as far back as 2500 B.C. The bottle was invented sometime around 1500 B.C. by Egyptian artisans. The Egyptians created lovely glassware. They made delightful tiny glass vases, tall-rim jars adorned with flamingos. Before glassblowing was developed in the 1st century B.C. “core glass” vessels were made by forming the glass around a solid metal rod that was taken out as the glass cooled.

Some of the most beautiful works of Egyptian art are blue pear-size hippopotami made of faience of clay and glazed in vivid blue glass. One of these hippos is upside down and has a broken leg, these were talisman placed with the dead. Their aim is scare off attacks by hippos in the journey in the afterlife. Scarab beetles were not just decorative items. One their undersides were written short tributes or accounts. A potato-size scarab produced under Amenhotep III commemorated the pharaohs skill as a hunter and describes how he killed “102 fearful lions: during the first 11 years of his reign.

The Egyptians created lovely glassware. They made delightful tiny glass vases, tall-rim jars adorned with flamingos. Before glassblowing was developed in the 1st century B.C. “core glass” vessels were made by forming the glass around a solid metal rod that was taken out as the glass cooled. Some have suggested that the bottle was invented sometime around 1500 B.C. by Egyptian artisans.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Glass: An Interdisciplinary Exploration” by Julian Henderson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Treasures of Ancient Egypt” by Nigel Fletcher-Jones (2019) Amazon.com;

Tutankhamun's Trumpet: Ancient Egypt in 100 Objects from the Boy-King's Tomb

by Toby Wilkinson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry: 50 Masterpieces of Art and Design” by Nigel Fletcher-Jones (2020) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Highlights of the Egyptian Museum” by Zahi Hawass (2011) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum”

by Edna R. Russmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt At The Louvre” by Guillemette & Marie-Helene Rutschowscaya & Christiane Ziegler (trans Lisa Davidson). Andreu (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egypt and the Ancient Near East”

by New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Peter F Dorman, et al. (1988) Amazon.com;

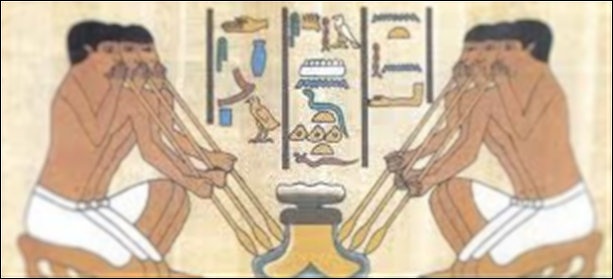

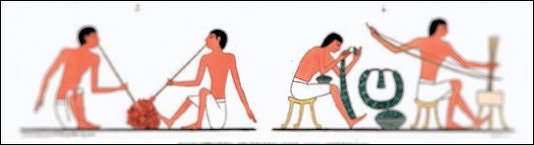

First Appearance of Glass in Ancient Egypt

Glassmaking — in the form of making beads — was known in ancient Egypt as far back as 2500 B.C. Whether this is real glassmaking is a matter of debate. A small glass vase in the British Museum bearing the name of Thutmose III (reigned 1479 to 1425 B.C.) is considered one the oldest example of glassmaking known. Two pictures which in all probability represent glass-blowing belong to the time of the Middle and the New Kingdom. The older of the two represents two men sitting by a fire blowing into tubes, at the lower end of which is seen a green ball — the glass which is being blown. In the later picture two workmen are blowing together through their tubes into a large jug, whilst a third has the green ball at the end of his tube. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The pictures of the time of the Old Kingdom, on the other hand, which have been supposed to represent glass-blowing, may probably be otherwise explained. In these representations five or six men are seated round a curious object which may be a small clay furnace; they are blowing through tubes which are provided with a point in front. In the inscriptions we read that the melting of a certain substance. The blowing is to fan the glow of the furnace. The pictures of working in metal to which we must now turn, show us that this explanation is probably accurate.

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Glass in ancient Egypt appeared in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.). It was a novel and highly prized material, which quickly found favor with the elite. The first known glass sculpture in the round depicted the Egyptian ruler Amenhotep II. The purposes for which glass was used overlap with those traditionally known for objects made in faience, and both materials can be regarded as artificial versions of semiprecious stones, notably turquoise, lapis lazuli, and green feldspar. The techniques by which glass was worked in the Pharaonic period fall into two broad groups—the forming of vessels around a friable core, which was subsequently removed, and the casting of glass in molds to make solid objects. The vessels produced by core forming were almost invariably small, a matter of a few centimeters in height, and were mainly used for precious substances such as unguents. Cast items included sculpture as well as inlays and small amulets. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Although there are reports of examples of glass dating before the New Kingdom, most of these are unconfirmed or uncertain, and one must distinguish between glass, which was intentionally produced, and that arrived at “accidentally.” To this latter category should be assigned small objects of glass, which were actually intended as faience but which have lost their silica core and so become glass. Since the basic ingredients of glass and faience are the same (silica, lime, and soda), it is not surprising to find some blurring of the groups when particular heating conditions occur.

“As a new material in Egypt, glass of the New Kingdom seems to have enjoyed a relatively high status. Indeed, some of the earliest pieces we know about bear the names of Hatshepsut (clear colorless name beads) and of Thutmose III (vessels); it seems to have been regarded as a material suitable for royal gifts, such as shabtis. Apparently glass sculpture in the round is an Egyptian innovation. It is commonly suggested that glass might have been a royal monopoly during the New Kingdom. However, this is an oversimplification, and Barry Kemp has pointed out that we know of no such concept nor of sumptuary laws for Egypt at this time. Nonetheless, it does appear that the actual making of raw glass might have been under state control at least until the end of the 18th Dynasty. That individuals of lower status gradually gained increasing access to glass should not be surprising. As the material became more common, it was used for a greater range of items and spread beyond the upper echelons of society.

Libyan Desert Glass — From a Meteor

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: Among the treasures discovered in King Tut’s tomb is an elaborate pectoral with a central scarab carved from a canary-yellow material called Libyan Desert glass. Found in the sand dunes of Egypt’s western desert, the glass was formed about 29 million years ago when a quantity of quartz melted at a temperature in excess of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which is hotter than the inside of a volcano. Scholars have long debated whether the yellow glass was created by a meteor that exploded aboveground or by a meteorite impact. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

“To test these hypotheses, geologist Aaron Cavosie of Curtin University searched glass samples for grains of the mineral zircon that hadn’t broken down under the intense heat that formed the glass. He identified a small number of preserved zircon grains whose crystal orientation indicated that they had transformed from reidite, a mineral that can only be formed by a meteorite strike. “This provides the first bulletproof evidence that Libyan Desert glass was formed by a meteorite impact,” says Cavosie. No impact crater resulting from such an event has ever been located, he explains, though it may lie beneath shifting dunes or may have eroded to such a degree that it’s no longer distinguishable on the landscape.

Faience in Ancient Egypt

faience hippo

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Faience has been described as “the first high-tech ceramic”, which aptly describes its artificial nature. Unlike conventional, clay-based ceramics, the raw material of faience is a mixture of silica (quartz), alkali (soda), and lime reacted together during firing to make a new medium, quite different in nature to its constituents. The Egyptians referred to the material as THnt (tjehenet) “that which is brilliant, scintillating, or dazzling,” in view of its reflective qualities, which they associated with the shiny surfaces of semiprecious stones. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Faience derives its modern name from its bright colors, which reminded early travelers to Egypt of “Fayence,” a colorful tin-glazed pottery that they knew from late medieval times and that took its name from the town of Faenza in northern Italy (confusingly, this pottery is itself now usually called majolica). The color most associated with the material is blue or blue-green and was probably produced in imitation of semiprecious stones such as turquoise and green feldspar, as well as lapis lazuli. The Egyptian name for the material was THnt (tjehenet), meaning “brilliant” or “dazzling” in reference to its brilliant shine, like that of the stones it was imitating.

“The origin of faience is probably to be sought in the Egyptian desire for semiprecious stones, not least those with the reflective blue color of the sky. It may have been the wish to replicate these that led to the glazing of steatite (soapstone, which hardens to become enstatite on firing) and quartz. The glazing of these stones developed as early as Predynastic times, when a soda-lime-silicate glaze was applied over the carved stones. Peltenburg has made the point that faience glazing was an essentially “cold working” technology, unlike glass, which was “hot worked.” By this is meant that the faience worker prepared his object and glazing materials cold, the firing of the object being done at a later stage. This technique also applies to the glazing of stone and indicates a clear link between craftsmen in semiprecious stones and glazing in the earliest phase of the production of glazed materials.

See Separate Article: FAIENCE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Glass-Making in Ancient Egypt

Joel R. Siebring of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “Glass-making technology initially began in Egypt with the manufacture of small beads in the pre-dynastic era. There is little or no evidence of glass technology until the XVIII Dynasty. The technology was a result of the process of firing clay pots. The sand and slag utilized in making clay pots melted together to make glass. Early examples of glass manufacture were in the form of beads made from the glass nuggets. It was determined that when metal oxides were added to the glass nuggets, various color hues resulted. The foundattion for this technology may have been in the development of bronze technology, adding different elements to copper to make bronze. There is also early evidence for glass blowing.” [Source: Joel R. Siebring, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Egyptian glass jar

Andrew Shortland of Cranfield University wrote: “Glass production starts in the second half of the sixteenth century B.C.. Glass was produced from the combination of quartzite pebbles with a plant ash flux, usually with the addition of copper, cobalt, antimony or manganese colorants, and opacifiers. The earliest surviving glassmaking workshop is a subject of debate since archaeological evidence for glass production is rare and often equivocal. No glassmaking factories have yet been found in Mesopotamia or Northern Syria, but several candidates are known from ancient Egypt, including the sites of Malqata, Amarna, and Qantir. This is still very much a topic of current research, both through archaeological investigation and scientific analysis. [Source: Andrew Shortland, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Objects of glass first appear in the archaeological record of Egypt in the reign of Thutmose III. The origin of the invention of glass is not clear, with both Egypt and Mesopotamia being proposed. However, the earliest datable glass and hence glass production seems to come from Mesopotamia in the last half of the sixteenth century B.C.. It seems to be imported into Egypt for the first time in quantity as tribute following the successful campaigns of Thutmose III in the early years of his reign. Evidence for the production of glass is rare in the archaeological record of any period, but especially of the earliest eras. There may be several reasons for this rarity—perhaps there were initially a very small number of factories and perhaps of limited extent. However, one of the major reasons for their rarity has probably to do with the difficulty of identifying such facilities. The production of glass objects can be divided into two clear stages: glassmaking and glassworking. “Glassmaking” is the production of glass from the raw materials, whereas “glassworking” is the transformation of raw glass into finished objects. Theoretically, these could both be done in the same place, but in practice, in the ancient world, they seem to have often been split into two different sites. Long range trade in raw glass is supported by the late fourteenth century B.C. Uluburun shipwreck. Its cargo included at least 175 glass ingots; judging from their chemical composition, many, but not all, of them were manufactured in Egypt. To date, no glassmaking factory has been found in Mesopotamia at all, but there are several proposed in Egypt, as discussed below.

Raw Materials for Making Glass in Ancient Egypt

Andrew Shortland of Cranfield University wrote: “The main raw material for glass production is silica, thought to be in the form of quartzite pebbles in the case of Egyptian glasses. These pebbles have a very high melting temperature, around 1700°C. In order to produce a glass from them, a plant ash flux is added. This lowers the temperature for the production of glass to around 1100°C, which was achievable in an ancient furnace. Almost all of the glass in Egypt was colored and frequently opacified. Light and mid-blue glasses were produced from copper in the form of bronze or copper scale, which was added to the melt. Lead isotopic analysis suggests that the copper colorant has the same source as the copper used in Egyptian tools and weapons. [Source: Andrew Shortland, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Darker blue glasses were often made with a cobalt colorant; this colorant has a particular pattern of trace element impurities (high alumina, manganese, nickel, and zinc), which has enabled the cobalt colorant to be sourced to cobalt bearing alums of the Western Oases of Egypt. The blues are the most common colors in the glasses and frequently form the body glass for the core formed vessels. The opacifier calcium antimonate occurs in white glasses, which is formed by adding antimony to the glass melt and allowing it to cool.

“The source of the antimony is unknown, but it is a rare element, and it is possible that the source might be as far away as the Caucasus. The lead antimonate opacifier has been identified in yellow glasses. Once again, the Caucasus may be the source of the antimony, but it is likely that the lead comes from local Egyptian mines, most notably Gebel Zeit on the Red Sea coast, which was exploited in the New Kingdom for the lead sulphide galena for use in eye pigments or kohl. Mixing blue glasses and these opacifiers gives opaque blue and green colors, respectively. The final colors in glass are pink, purple, and black—all colored with manganese of unknown source—and red, which again uses copper.”

Glass Production in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian glass vessel

Andrew Shortland of Cranfield University wrote: ““Little is known about the way glass was produced. It is not a subject that was written about in Egyptian texts and, unusually, does not seem to be depicted in any of the fairly common tomb scenes, which show metal, pottery, or stone production. However, there is evidence in the form of texts from the Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, the information of which is thought to date to the second millennium B.C.. These detail recipes and furnace conditions; however, many of the words used are difficult to translate and some have strong magical and religious elements, which makes interpretation of the texts difficult. The best evidence therefore comes from analysis of the glass itself and rare archaeological finds of glassworking or glassmaking factories.” [Source: Andrew Shortland, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The treatment of glass must be divided into two parts: the making of glass from its raw materials and its working from already processed glass. The introduction of glass blowing in the first century B.C. and the incorporation of Egypt into the economy of the Roman state radically altered the production, distribution, and status of glass. Processed glass may be in the form of ingots, newly made from the raw materials (or possibly from recycled materials), or in the form of scrap glass, known as cullet. Our present knowledge of early Egyptian glass does not usually allow us to differentiate glass made from new materials from that made from cullet. However, because vessel glass was frequently polychrome, it would be difficult to recycle, unless vessels and other products were first separated by color (such as some inlays, beads, etc.). A glass ingot from Amarna, now in the collection of the Liverpool University Museum, may be the result of remelting/recycling of glass, but this is by no means certain—recycled glass is not necessarily obvious in macroscopic examination. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The earliest glass in Egypt was probably imported from elsewhere in the Near East, and since much of that production was for polychrome vessels, it is unlikely that it was recycled. Similarly, the very earliest local production in Egypt would have used freshly produced glass, though we should not rule out limited recycling of single color glass, particularly since this was a precious raw material. By the time the beakers of Neskhons (wife of Pinedjem II) of the 21st Dynasty were produced, it is possible that recycled glass, albeit of a new natron-based composition, may have been in use. However, although the Neskhons pieces lack the quality of earlier vessels, analysis of their composition has not suggested recycling.”

Glassworking Production in Ancient Egypt

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “While glass itself was a new material in Egypt and as such seems to have enjoyed a high status, it was not used in the creation of innovative forms. Glass seems rather to have been regarded as an extension of faience and, perhaps by implication, of semiprecious stones such as turquoise, lapis lazuli, and green feldspar. The connection between these materials is probably through color and brilliance. Faience was regarded as a substitute for semiprecious stones, not necessarily inferior to them but of a different and artificial material. All carried connotations of the heavens and the brilliance of the skies. Since the body color of much of the earliest glass is also blue, it seems to have been regarded as yet another representation of this heavenly blue brilliance. That such was the case is probably reflected in the term “Menkheperura (i.e. Thutmose III) lapis lazuli” for a material believed to be glass, given in the Annals of Thutmose III at Karnak and sharing the color of the semiprecious stone. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“It is possible that the association with precious stones might have led to the production of vessels in shapes that were already produced in faience, itself imitating forms known in stone. In other words, artificial stones such as faience and glass were used to make traditional stone vessel shapes. However, these shapes are not ones normally found in turquoise, lapis, or feldspar, but more commonly in travertine/calcite (Egyptian “alabaster”) or hard stones, and one must consider why this should be.

“A possible answer may be found in the history of these materials. Once faience started to be developed, one of the means by which it could be shaped was by abrasion, essentially “carving” from a block of material, albeit often a partly shaped block. From small vessels, the kind of things which lapidaries (gemstone cutters) may have produced in semiprecious stone, to larger vessels is a relatively small step. These larger faience imitations of stone were being made in the typical blue color, so it would be logical for glass vessels, also usually in blue base glass, to follow this tradition.

“Further support for the idea that glass followed the traditions established by faience makers may come from the way in which glass first arrived in Egypt. Both Petrie and Oppenheim believe that its making may have been introduced by glassmakers brought to the country as captives from the Near East. If this was so, and they were induced to establish a new industry, it is most likely that they would be integrated among Egyptian specialists who worked on material that shared some of the properties and technology of glass—the makers of the artificial precious stone: faience. The work of Petrie at Amarna makes it clear that faience and glassmaking/glassworking activities went on in close proximity to one another, a finding confirmed by the recent work by the Egypt Exploration Society. Part of this technological link is probably the use of heat in the final stage of production.

“It is interesting to note also that some of the earliest glass vessels were treated as though they were of stone in that, after casting, they were drilled to make them hollow. These pieces seem to belong to the phase in which glass was coming into Egypt perhaps in the form of ingots from the Near East, or was first being made locally at a time when its properties were still not fully understood. Thus we have an artificial, high-tech material being treated as though it were stone. This combination of working practices and the embedding of a new craft into an old established one is an area that requires further research.”

Cold Working Glassworking in Ancient Egypt

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “However the earliest raw glass arrived in Egypt, be it as ingots or as locally made glass, the earliest stages in its manufacture into objects require heat at some stage. In order to make useful objects, raw glass would have been reheated and cast, probably into blocks with the approximate shape of the desired object. The glass would then have been annealed, an essential process in glassworking involving the slow cooling of the glass object, be it glass block or glass vessel. This cooling process allows the stresses developed in the hot glass to be gradually reduced and released so that the cooled object will not shatter. A piece of glass, which is simply put aside to cool in the workshop, would quickly crack or explode. Annealing may take place in a chamber to the side of, or above, the main furnace or might be carried out in a separate structure. It may take several days to anneal large pieces. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The earliest glass, once it had been annealed, was worked cold. The interior of a vessel might thus have been drilled out using a bow drill, probably with a copper cylinder as the drill bit just as Stocks has demonstrated for stoneworking. This practice would have to have been carried out with great care because glass, like other siliceous materials such as flint, will fracture conchoidally (shell shaped), and glass spalls around the drill would be difficult to disguise. It is notable that the edges of rims and feet on early glass vessels including a kohl pot, which was made in this way, are often covered in sheet gold, perhaps covering areas where the glass was prone to chipping in use or where it had been damaged during the polishing stage of the operation.

“The casting and cold working of glass was not confined to the earliest phases of Egyptian glass history. However, its use in the manufacture of hollow forms seems to have been limited to its earliest phase. In the later reign of Tutankhamen, the technique of casting and cold working was used to produce two headrests. One of these, in dark blue glass and with an incised inscription, had the edge of the upper part covered by sheet gold, while that in light blue glass was made in two parts joined by a wooden dowel, the join being covered by a band of gold foil. Both would have required very careful working by skilled lapidaries after the form was cast in glass.”

Hot Working Glassworking in Ancient Egypt

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The other main branch of the glassworking technique is to use heat in the active shaping of the object, that is to “hot work” it. Gathering. At its simplest, this involved gathering a small blob of glass from the furnace and then piercing it to form a bead. This was most easily achieved simply by gathering the glass around a rod so that it was ready-pierced. The shape of the bead was manipulated with tools and by rolling it on a flat surface known as a marver. Thus beads of spherical, cylindrical, or faceted shapes could be produced. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“A hot thread of molten glass could also be drawn out from the furnace, allowed to solidify, and then be gently reheated in order to be shaped. In this way the simple earrings of the New Kingdom might have been produced, along with items such as applicator rods for kohl vessels and similar straightforward/plain pieces. Like all glass objects, once shaped and, in the case of beads, removed from their rod, they would need to be annealed.

“Molding/Slumping. In Pharaonic Egypt, molding or slumping was used to produce open form vessels, represented by the conglomerate glass pieces known from Malqata and elsewhere. Here fragments of glass of different colors were placed together and heated so that they fused together into a single continuous plane. They were perhaps first fused into a disc or oval shape and then reheated so that the fused disc slumped over a form or into a mold, forming a dish or bowl. Glass pieces could also be heated together in a mold, though this would be more difficult to achieve satisfactorily. A rim, in the form of a softened glass rod, was sometimes added to the vessel. This technique might be regarded as the origin of what was to become mosaic glass, a specialty of the Roman Period.The making of inlays and occasionally of amulets was apparently achieved by using open-face molds just as in the production of faience. The molds were probably made of fired clay or, more rarely, stone and have not been discerned with certainty from those used for faience.

“Lost wax. There remains the question of the manufacture of small items such as amulets and inlays other than those that may have been made in open-face molds. A few small pieces in the round exist and seem to have been made by the lost wax process. In this method, a wax image of the object was produced and had clay pressed around it. The object was then heated, which fired the clay and melted away the wax leaving a void in the shape of the object. The void was then filled with the intended medium for the object—in this case glass. The lost wax technique is best known for casting gold or copper alloy, where the medium is very fluid, and would not be particularly well suited to glass, where the medium is quite viscous. It may be that powdered glass was continually added to the heated mold until it was filled, in this way small items can be produced without the risk of trapping large air bubbles. Whatever means was used, the finished object would require considerable retouching. Shabtis made in glass might have been produced by the lost wax process, but this is uncertain, and Cooney states that they were extensively reworked after casting in whatever kind of mold was used.”

Core Forming Glass in Ancient Egypt

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Core forming. A process known as core forming was the most widely used method for producing glass vessels from the New Kingdom into Hellenistic times. It was a more difficult and time consuming operation than simple gathering and became the common process for making glass vessels once the properties of glass were better understood and confidence in its use had been achieved. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“In this method a core made from clay mixed with dung and plant fiber was shaped in the form of the vessel interior. It was formed around a handling rod, which allowed the piece to be manipulated. This core was then dried and coated with glass. The exact means of coating has been subject to much debate, with some researchers suggesting that the core was rolled in powdered glass or covered by the application of chunks of softened glass. It has also been suggested the core was dipped into a pot of molten glass or that molten glass was trailed onto the core. Whatever means was used, the glass was then rolled on a marver (smooth stone slab) to give it a more even thickness over the core and get the basic shape of the vessel exterior. This process required many reheatings of the core and the glass surrounding it and much work at the marver.

“Once the core had been covered and a fairly uniform thickness of glass achieved, decorative trails might have been added to the vessel body. This was done by softening rods of glass and marvering them into the body. By using a blade to draw the trails up or down the body, it was possible to form them into chevrons or swags, common patterns on Egyptian glass vessels. Rims were added to core formed pieces by using pincers to draw glass from the vessel wall or by adding rings of glass to the top of the vessel. Such rims were sometimes embellished by adding a trail of glass in a contrasting color. The same technique could be used for adding a foot to a vessel, while handles were made by adding a gather of glass to the vessel wall.

“The whole object, still containing its core, would then be allowed to anneal slowly. This did not, of course, complete the process and some skill was still required in order to remove the core. Removal of the handling rod, probably at the point when the piece was placed in the annealing oven, left a void at the axis of the core, and this could gradually be enlarged by abrading the friable material inside the vessel away. By careful abrasion most of the core could be broken up and tipped out through the neck of the vessel. The contact zone between the vessel and the core inevitably preserved part of the core; this can regularly be observed under the shoulders of broken vessels. While most ancient Egyptian glass is opaque or translucent rather than transparent, this lack of clarity is no doubt added to by the remains of the core.

“It is possible that the need to use a core, and the knowledge that it could not be fully removed, may have encouraged the use of strongly colored body glasses rather than the development of transparent colorless glass. The name beads of Hatshepsut and Senenmut indicate that such glass could be made in the ancient world at an early date, but did not find use in vessels.”

Glass Use and Discard in Ancient Egypt

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The purpose of glass objects has already been touched upon, namely as items of personal adornment, inlays, and containers. For small items of adornment the use of glass was essentially identical to that of faience and even stone—serving as beads or amulets whose color and shape had particular symbolic or decorative importance. However, at least in its earliest phases, glass was a new material, apparently conjured up from unlikely raw materials, which alone shared few if any of the properties of the finished item. The seemingly miraculous quality of this rare new material may have given glass a status above that of faience, making it a prestige product destined for the use of the high elite of Egyptian society. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The only items of glass sculpture in the round, which are known from ancient Egypt, were associated with pharaoh or his highest officials. That figures of the king or shabtis for his nobles were made in the material emphasizes its importance as well as its acceptance as a substitute, though not an inferior one, for faience or stone. Glass had a status, which rendered it suitable for the afterlife as well as the earthly one. This view is further reinforced by the use of glass inlays in the gold mask of Tutankhamen rather than lapis lazuli and the manufacture of head rests for his tomb in glass. The use of materials in the ancient world cannot be judged by the value we place on them today—just as the iron in Tutankhamen’s tomb was a novel, high-tech material, so glass seems to have enjoyed royal approval as a new and fascinating product.

“The use of glass containers was associated with expensive contents. Vessels served to hold perfumes, oils, and unguents rather than common items. Indeed, the use of glass simply as a convenient and quickly produced container is a result of glassblowing, a technique introduced in Roman times from the first century B.C.. The time taken to produce a glass vessel by the core forming technique meant that each was an individually crafted work of art, whose form and appearance may well have been as important and as valued as the contents.

“The questions of glass discard and recycling have not been studied for ancient Egypt. There has been little work on the question of discard of materials in general. What is clear is that the earliest glass had a considerable value, and most of our glass finds of vessels are from funerary contexts. Multi-colored glass was difficult to recycle because the colors become merged and yield a dirty opaque glass. While the addition of a strong colorant such as cobalt might alleviate this problem, it is more likely that only monochrome glass was recycled. It might be expected that with a newly established craft, whose practitioners were few and worked in a limited number of centers, the return of broken glass to the workshops would be very limited and difficult to achieve. More likely, broken fragments might have been treasured by more low ranking individuals, pierced as beads or kept as curios. Vessels or other items, which broke at the workshops, could of course be easily recycled. Scientific examination of early glasses from Egypt is not as yet sufficiently advanced for much to be said about the occurrence or scale of recycling.”

Discovery of Glass Factories in Amarna

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “In Egypt and the rest of the Middle East in the 13th century B.C., bronze was the heavy metal of power, and glass the rare commodity coveted by the powerful, who treasured glass jewelry, figurines and decorative vessels and exchanged them as prestige gifts on a par with semiprecious stones. But definitive evidence of the earliest glass production long eluded archaeologists. They had found scatterings of glassware throughout the Middle East as early as the 16th century B.C. and workshops where artisans fashioned glass into finished objects, but they had never found an ancient factory where they were convinced glass had been made from its raw materials. [Source:John Noble Wilford, New York Times, June 21, 2005 **]

"In 2005 two archaeologists reported finding such a factory in the ruins of an Egyptian industrial complex from the time of Rameses the Great. The well-known site, Qantir-Piramesses, in the eastern Nile delta, flourished in the 13th century B.C. as a northern capital of the pharaohs. Dr. Thilo Rehren of the Institute of Archaeology at University College London told the New York Times, "This is the first ever direct evidence for any glassmaking in the entire Late Bronze Age." **

"Other experts familiar with the research said the findings were important for reconstructing the ancient technology of glassmaking. But some questioned the claim that Qantir represented the first evidence of primary glass production, citing previous findings in Egypt at Amarna, which are dated a century earlier. Dr. Rehren and Dr. Edgar B. Pusch of the Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, said they had excavated cylindrical crucibles and remains of glass raw materials in various stages of production. The site yielded samples of quartz grains, thought to be the main silica source of glassmaking in the Bronze Age. **

"Archaeologists generally credit Mesopotamia as the original and primary source of glass, as early as the 16th century B.C.. But no factories have been uncovered there. More than a century ago, the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie discovered what he considered evidence of Bronze Age glass production at Amarna. The site is dated to the 14th-century reign of Akhenaten and therefore earlier than Qantir. But skeptics suspected that the Amarna glassworks was not a production plant, only a place where glass ingots were reworked into finished goods. And if it was a primary factory, why would records show Akhenaten requesting that glass be shipped to Egypt? **

Ancient Egyptian Glass Factories

Andrew Shortland of Cranfield University wrote: “Analysis of the glass has shown that there were at least two different factory sites operating in the fourteenth century B.C., at least one in Egypt and one in Mesopotamia or Northern Syria . Early glassmaking or glassworking factories have been identified at the sites of Malqata, Amarna, el-Lisht, and Qantir...Two further sites, Menshiyeh and Kom Medinet Ghurab, have been suggested as areas of glass production. However, there is considerable doubt as to the dating and function of the sites, and they “cannot feature significantly in discussions of New Kingdom glass production”. [Source: Andrew Shortland, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Malqata: The site of Malqata on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes was excavated by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Egyptian Expedition between 1910 and 1921. Here, within the workmen’s quarter of an extensive palace complex built by Amenhotep III, the earliest evidence for a glassmaking or glassworking site in the world was found. The excavators record finding crucible and glass slag, but the objects themselves were not retained by the museum and are thus not available for modern study. Glassworking debris, such as rods, drips, and trails, was abundant.

“Petrie stated that he had found “the sites of three or four glass factories, and two large glazing works… though the actual workrooms had almost vanished” at the site of Amarna in Middle Egypt in the late nineteenth century. Regrettably, he does not state where these workshops were, but later work has shown that they lay within the southern end of the city, amongst the poorer quality housing. An Egypt Exploration Society expedition led by Paul Nicholson was working on one of these factories, O45.1, through the 1990s. Two kilns 2 meters in diameter were uncovered; they were described as thick walled and highly vitrified, with a sacrificial, regularly replaced lining, and associated with a large amount of khorfush, the local word for black ‘slag’ (in this case, the melted clay lining of the furnace, which has solidified on cooling). A third smaller kiln was found apparently associated with the other two and of a type recognized by Nicholson to be a pottery kiln. Associated with the site were frit, melted glass, glass rods, and fragments of cylindrical vessels. All of this strongly suggests that this site designated O45.1 was used for the manufacture of vitreous materials although not necessarily glassmaking.

“El-Lisht: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Egyptian Expedition also excavated the site of glass production at el-Lisht. This site was situated in a technological complex dated to 1295 - 1070 B.C., on the northern and eastern sides of the much earlier 12th Dynasty pyramid of Amenemhat I. Working between 1906 and the mid 1930s, they uncovered glass crucibles and slags, glass working debris in the form of rods, drips, and wasters, and a single large glass ‘ingot’. The factory seemed to be producing glass beads, rings, pendants, and inlays. Once again, significant amounts of the finds were not retained, making it difficult to interpret the function of the site.

“Qantir: A series of glass workshops have been hypothesized at Qantir-Pi-Ramesse in the eastern Nile Delta dating to 1250 - 1200 B.C.. This site is different to the others described above in that it has relatively little glassworking debris. Instead, it has a large number of cylindrical vessels or glass-coloring crucibles for which no domestic parallel is known. So far, about 1100 fragments have been recovered, representing a minimum of 250 to 300 vessels. One of these crucibles, 00/0344, inventory number 3108, is filled with a heavily corroded block of raw glass, which seems to represent a glassmaking charge that was abandoned before the batch material had fused completely—in effect, preserving much of the original raw material. The site seems to have specialized in the production of red glass, a color that is very rare at the other glass sites above.

“The Earliest Glass Factory? As discussed above, there is a distinction to be drawn between glassmaking factories and glassworking areas. Malqata, Amarna, and el- Lisht all contain significant amounts of glassworking debris, so this is what was obviously going on here. However, the presence of glassmaking is much harder to derive. It has been claimed that Qantir represents the earliest surviving glassmaking factory on the basis of the crucible described above, the only example of a glass batch preserved as a charge before being fully vitrified in the furnace. However, others have claimed that the Amarna workshop of O45.1 is a glassmaking facility on the basis of the presence of high temperature kilns and frits that appear to be colorants. Too many of the finds from el-Lisht and Malqata have been lost to enable them to be considered. This is still the subject of much research, and only further excavation and analysis is likely to resolve the issue for certain.”

Production at Ancient Egypt's Glass Factories

“One well-preserved crucible,” Wilford wrote, “contained a block of raw glass, and many other vessels held semifinished glass and some fragments that had been colored blue, red and purple. In the June 17, 2005 issue of the journal Science, the two archaeologists reported, "We could identify several hundred individual vessels used in glassmaking and coloring; more than 90 percent of these are crucibles, the rest being jars." [Source:John Noble Wilford, New York Times, June 21, 2005 **]

"The archaeologists concluded that this was a large-scale glassmaking operation. In the first step of production, a mixture of crushed quartz and plant ash was heated at a low temperature in ceramic vessels. Salt contaminants were then washed away from the semifinished glass. Next, the glass powder was mixed with coloring minerals and heated inside the crucibles. At the end, the containers would have been smashed to remove the glass ingots. Dr. Caroline M. Jackson, an archaeologist at the University of Sheffield in England, said the new finds "convincingly show that the Egyptians were making their own glass in large specialized facilities that were under royal control." **

"Writing in an accompanying journal article, Dr. Jackson noted that at Qantir, copper was used to color glass either red or blue, a relatively difficult process, and that glass ingots were the end product. This seemed to settle a dispute among scholars: whether the Egyptians at this time were able to produce and export glass, or only rework glass into luxury goods, like colorful beads and containers for perfumes. **

"Dr. Paul Nicholson, an archaeologist at Cardiff University in Wales, told the New York Times that new excavations at Amarna had yielded two large furnaces, "which I believe are for use in glass production." No such furnaces have so far been uncovered at Qantir, he noted. "It is likely that neither Amarna nor Qantir are actually the earliest in Egypt," Nicholson said but the Qantir evidence "is important and Thilo has reconstructed a possible technological sequence from it.” At least, archaeologists said, Amarna and now Qantir affirm that even if the technology probably began in Mesopotamia, the Egyptians seemed to acquire it in time and left direct evidence of how glass was made in the Late Bronze Age. **

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except glass making Saudi Aramco and Pinterest and the map, Science magazine

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024