Home | Category: Art and Architecture

OBELISKS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

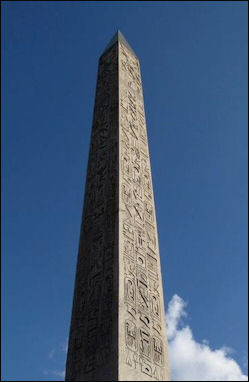

Obelisk de la Concorde A symbol of Egypt, second only to the pyramid, an obelisk is a four-sided pillar hewn from a single block of stone. Resembling the Washington Monument, they have highly polished surfaces carved with hieroglyphics and were originally capped with gold, copper or electrum, which shimmered in the sun light. "Obelisk" is a Greek word that means "meat skewer." They were known in Egyptian as tekhenu, which means “to pierce.” [Source: Evan Hadingham, Smithsonian]

Obelisks are believed to be advanced versions of pointed stones known as “ beneben” , which the Egyptians worshipped in prehistoric times as primordial mounds that arose from chaos. They rose high into the Egyptian sky, symbols of the pharaoh's power and served as fetishes honoring the sun-god Ra. They were often raised to mark important victories or the opening of a temple, or celebrated a coronation or other important event. Great care was taken making them, transporting them and raising them. Pliny the Elder wrote about kings names Ramses who roped his son to the top of an obelisk while it was being raised to drive home the point that special care was need to raise it.

Scores of obelisks were once found along the Nile. They were generally set up in pairs in front of temples; their inscriptions crowing the achievements of the pharaohs with lines like he will “exercise enduring kingship throughout eternity.” Less than half a dozen obelisks remain in Egypt. There are more in Rome (13) than in all of Egypt. Others are scattered around Europe and North America. Some of them were taken by Romans. Others were sold off by modern Egyptians to pay off debts.

According to Archaeology magazine: As the center of the worship of Ra, Heliopolis at one time boasted dozens of obelisks, only one of which remains in its original position. However, not all of Heliopolis’ obelisks have been lost. At least seven were taken from Egypt and raised in metropolitan centers across the world. One goal of the Heliopolis Project, a joint Egyptian-German excavation, is to determine where the obelisks originally stood in the sacred city and how they functioned as part of its religious rituals. [Source: Andrew Curry, March-April 2019]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Obelisks of Egypt: Skyscrapers of the Past” by Labib Habachi (1977) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra’s Needles: The Lost Obelisks of Egypt” by Bob Brier PhD, Christopher Douyard, et al. Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Statues” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Great Sculpture of Ancient Egypt” by Kazimierz Michalowski (1978) Amazon.com;

“Sphinx: History of a Monument” by Christiane Zivie-Coche and David Lorton (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Statues: Their Many Lives and Deaths” by Simon Connor (2022) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Egyptian Art” by Émile Prisse d'Avennes (1991) Amazon.com;

Making Obelisks

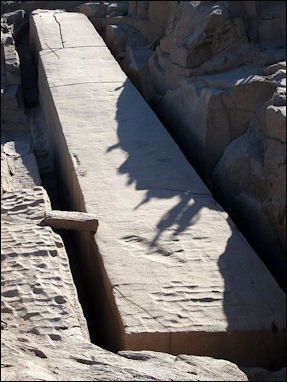

Unfinished Obelisk Most of the obelisks — and all the large ones — were hewn from the same granite quarry near the first cataract Aswan, where the delicate mottled pink granite, used to make statues, columns, bathtubs and sarcophagi, as well as obelisks, was found. Bronze and copper tools were too soft to chisel out the granite.

The obelisks were hammered in situ out of the stone. The quarry today is a collection of obelisk-shaped pits and shafts used to examine the quality of the rock. Much of what is known about obelisk making has been gleaned from the unfinished obelisk still in Aswan. Weighing over 1,000 tons it would have been the largest one ever made but cracked while being freed from the quarry bed. It was about 75 percent finished.

No chisel marks were found on the unfinished obelisk. It appears they removed by bashing channels in the rock with dolerite balls, weighing about eight pounds each. Dolerite is a stone that is harder than granite. Pits have been found with thousands of dolerite balls. The balls are believed to have been dropped repeatedly by rows of workers along the lines of the obelisk. The jobs was obviously arduous and cracking the rock was the biggest problem.

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “Extracted rock masses were dressed (trimmed) in the quarries with the same tools used to remove them. A new stone-dressing technology was introduced by the Romans in the Wadi Umm Shegilat quarry for pegmatitic diorite (var. 1). Here they used a toothless iron saw blade along with the locally available quartz sand as the abrasive to cut the sides of rectangular blocks and the ends of column drums. During all periods of Egyptian history, the quarry products were usually roughed out to something approaching their final form on site, and occasionally were carved to a nearly finished state. This not only reduced the weight of stone requiring transport, but also had the benefit of revealing any unacceptable flaws in the stone prior to its removal from the quarry. [Source: James A. Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Transporting Obelisks in Ancient Egypt

Making obelisks was obviously a difficult task but what was even more remarkable was moving and raising them. From the 16th century to the 13th century B.C., the obelisks were maneuvered to the Nile on logs or some other rollers or pulled on a sled lubricated with olive oil, and loaded on barges and transported to their destinations. How they were raised remains a mystery.

A rare view of an obelisk being moved is found in the walls of the temple of Queen Hatshepsut (ruled 1498-1483B.C.). It shows two obelisks being loaded end to end on a barge towed by 27 boats. The obelisks may have been put in place by hauling them up a ramp and then sliding them down the other side untilhe bottoms rested on their pedestals and then pulling them upright using ropes and scaffolding. The only thing holding the obelisks in place on their pedestals is gravity. They were tough. One in Alexandria was toppled by an earthquake in 1301 but it didn’t break.

Famous Obelisks

Obelisk in Rome Beginning with the Roman emperors Caligula and Nero, obelisks were greatly admired by world leaders and over the years they have been carted to many of the world's greatest cities, including Rome, Paris, Istanbul, and New York.

Obelisks are found in Central Park in New York, on the Thames embankment in London, and in Concorde Circle in Paris. The 220-ton, 69-foot-tall one in London was almost lost. The boat carrying it was hit by a storm and six men died after it was abandoned. The ship with obelisk was later found floating at sea. The obelisk was salvaged and sold to the British government for £2,000. The ones that ended up in New York were lowered using a special device — two iron saw horses with a pivit between them that clamped onto the obelisk’s center of gravity — developed by the engineers that built the Brooklyn Bridge. A wooden trestle was built to move it to its Central Park hilltop site.

Piazza San Giovanni in Laterno (Rome) contains the world's largest obelisk. Brought from Aswan, Egypt to Italy in A.D.357 by Emperor Constantius II and repositioned on the plaza in 1588, it was once 118 feet tall. Now it is 107½ feet tall and weighs 502 tons. The obelisk in St. Peter's Square was raised in 1586 with a 92-foot-high wooden tower outfit with pulleys by 900 men and 74 horses. The great obelisk at the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak is nearly 100 feet high and weighs about 323 tons — about the same as a 747 jumbo jet.

The world's largest unfinished obelisk is in Aswan. Probably commissioned by Queen Hatshepsut in 1490 B.C., it is 137 feet tall and weighs 1,287 tons. It was rendered unusable by a crack, and still is sitting in the quarry where it was hewn.

Raising an Obelisk

Obelisk in Luxor There are no historical records that show how the obelisks in ancient Egypt were raised. Possible methods include: 1) lowering the obelisk into a chamber filled with sand and removing the sand from below (this method was featured in Cecil B. DeMille's “Ten Commandments”); 2) placing the obelisk on a ramp and wedging it up and putting stones underneath it as it is raised. 3) dragging it up an incline and then easing it down to a pedestal with a hinge and pulling it upright.

In late summer 1999, Roger Hopkins and Mark Lehner teamed up with a NOVA crew to erect a 25-ton obelisk. This was the third attempt to erect a 25-ton obelisk; the first two, in 1994 and 1999, ended in failure. There were also two successful attempts to raise a 2-ton obelisk and a 9-ton obelisk. Finally in August–September 1999, after learning from their experiences, they were able to erect one successfully. [Source Wikipedia]

Initially, A team with 200 laborers, assembled by the NOVA public television series, attempted to raise a 43-foot-long, 40-ton granite obelisk without modern machinery. The team tested the sand method on a two-ton obelisk and found it didn't work very well because it was difficult to remove the sand evenly and maneuver the obelisk into place.

The NOVA team had the best luck with the hinge method. They slipped the obelisk down the ramp fairly easily so that it caught the hinge and slowly inched it upwards with levers and placed packing material underneath. The raised it to a 40-degree angle and found as the angle grew steeper, the supporting material became less stable. In the end the could not raise it with 200 men but felt that if they had 2,000 men they could do it.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024