Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ART

.jpg)

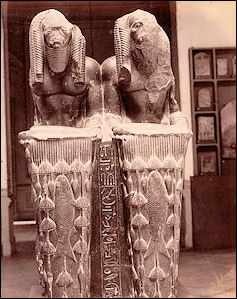

11th Dynasty funerary statue Although the ancient Egyptians had no word for “art” they revered beauty and produced architecture, reliefs, paintings, murals, statues, decorative arts, and a variety of crafts. Subjects in Egyptian art included gods, pharaohs, the Nile, gardening and everyday urban and rural life. Human figures, whether they were kings in battle, fishermen catching fish or village women washing clothes are presented in a kind of idealized form: healthy, young and contented.

So many splendid works of Egyptian art have come down to us today because they were made of durable materials like stone and clay and the hot desert air of Egypt has been ideal for preserving them. Most objects were excavated from the tombs of kings, queens and nobility.

The best collections of Egyptian art are found at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Egyptological Museum in Leiden, and the Fondazione Museo delle Antichita Egize di Torino in Turin, Italy. There is so much ancient Egyptian art out there that many museums have fine collections and lots more have at least a few pieces and a lot of art is in the hands of private collectors. Much of the art and artifacts housed in the British Museum came to Britain in the 19th century and were part of the booty of returning diplomats and aristocrats.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James (2025) Amazon.com;

"Artists of the Old Kingdom: Techniques and Achievements" edited by Naguib Kanawati, Alexandra Woods, and Effy Alexakis Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Egyptian Art” by Émile Prisse d'Avennes (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Statues: Their Many Lives and Deaths” by Simon Connor (2022) Amazon.com;

“Highlights of the Egyptian Museum” by Zahi Hawass (2011) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum”

by Edna R. Russmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt At The Louvre” by Guillemette & Marie-Helene Rutschowscaya & Christiane Ziegler (trans Lisa Davidson). Andreu (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egypt and the Ancient Near East”

by New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Peter F Dorman, et al. (1988) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Art, Death and Unchanging Egypt

Much of the ancient Egyptian art that has made it to us today was oriented towards death, the dead and the quest for the afterlife. The Egyptians believed that artistic renderings of images placed in tombs would become real and accompany the deceased to the afterlife. Some scholars say the Egyptian belief in the afterlife is what helped ancient Egypt survive even after the empire had died.

Plato once said that Egyptian art has not changed in 10,000 years although scholars prefer to use the word "enduring" and "continuous" there is some truth to Plato's remark. One dimensional figures with their left foot forward surrounded by symbols like falcons, papyrus reeds appeared around by 3000 B.C., and endured until about A.D. 500 with few changes.

The earliest wall paintings in tombs which date back to 3200 B.C. looked like glorified stick figures. By 3000 B.C., Egyptian art was in form were are familiar with today.

While ancient Egyptian art is regarded as static there have been some developments over time, with artists findings modes of expression within strict rules. While poses are often the same, faces and expressions can be highly individualized. It can be argued that Christian art was equally static. There are many images of Jesus on the Cross with individual works having their own modes of expression. See Expression Below

Mesopotamian Influences in Ancient Egyptian Art Seen in King Tut’s Grave Goods

Statues of Shepherd Kings In the 2010s a German-Egyptian project analyzed hundreds of embossed decorative gold items from King Tutankhamun (King Tut’s) grave for the first time. The fragmented gold pieces were boxed up shortly after they had been discovered and remained in museum storage until recently. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2018]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Experts have painstakingly reassembled the ornamental applications, which would have been attached to objects in the pharaoh’s tomb, such as quivers, bow cases, and bridles. They were surprised to detect decorative motifs foreign to Egyptian art at the time. Scenes such as fighting animals and goats at the tree of life were typical of Mesopotamian art, and their presence on the objects from Tutankhamun’s grave demonstrates how Egyptian artists were cognizant of and influenced by outside cultural styles that had seemingly passed to Egypt through the Levant.

Although chemical analyses of the gold artifacts with Egyptian motifs and those with foreign motifs showed that they had different chemical compositions and sources, it is not thought that the eastern-style objects were imported. Instead, they were likely created in workshops specializing in Mesopotamian styles.

Artists in Ancient Egypt

In most cases we have no idea who the artists were. Artists did not sign their names to works and objects tended to be created by teams who worked in workshops or on site. Stone cutters carved the hieroglyphics. Gem cutters and metal workers inserted precious stones and other objects into the eyes. And painters added the vivid colors. Often artists were employees of the state and their main duty was to make the pharaoh and those who employed him look good. The status of skilled artisans was a little bit below that of scribes.

During the Old Kingdom the high priest of Memphis bore the title of “chief leader of the artists," and really exercised this office. It is quite explicable that the duties of this high ecclesiastic comprehended the care of art, for as his god was considered the artist amongst the gods, so the chief servant of Ptah would also necessarily be the chief artist, just as the priests of the goddess of truth were at the same time the guardians of justice. The artists of lower rank during the Old Kingdom also gladly called themselves after their divine prototype. If we could deduce any facts from the priestly titles of later times, we might conclude that this was also the case at all periods, for aslong as there existed a high priest of Ptah, he was called the “chief leader of the artists. " We can scarcely believe however that this was so; the artists were differently organised in later times, although Ptah of Memphis still remained their patron genius. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In the Middle Kingdom, under the eleventh dynasty, we meet with Mertesen, “superintendent of the artists, the painter, and sculptor, who boasts of his special artistic power. He was “an artist, wise in his art, and appearing as first in that which he knew; he understood how to indicate that his figures were walking or standing still, and was possessed of secrets of technical skill." In addition to Mertesen, we hear of several painters of about this period," for instance, a special “painter in the royal house," and another who calls himself the superintendent of the necropolis of Abydos; this place was therefore probably the sphere of his work.

During the New Kingdom we find a “superintendent of all the artists of the king," and in his tomb are represented all the workshops in which all the necessary architectural parts were carved and painted “for all the buildings which were under his superintendence. " As a rule, the artists of this time belonged to the department of the treasury," and the chief royal “superintendent of the house of silver “reckoned amongst his officials two “deputies of the house of silver," and with them also two “deputies of the artists of the house of silver," also a “superintendent of the works in the place of such as in the necropolis) — who was at the same time “superintendent of the sculptors, — a “scribe of the painters," a “chief of the painters," and an “architect in the royal house of silver."

The administration of the great temple of Amun comes forward prominently by the side of that of the state; in this department, as in all others, the Theban god had his own “painters," and “chief of the painters," '' “sculptors," and “chief of the sculptors," and a crowd of other artists, who, as we have seen above, were under the supervision of the second prophet.

Many artists belonged to the upper classes; at the beginning of the 18th dynasty two “painters of Amun “were members of the distinguished nomarch family of El Kab, and under the twentieth dynasty a painter was father-in-law to a deputy-governor of Nubia. ' It is also interesting to see how tenaciously many families kept to the artistic profession. The office of “chief of the painters of Amun “remained for seven generations in one family, and that of his “chief sculptor “was certainly inherited from the father by the son and the grandson; ' in both cases the younger sons of the family were also painters and sculptors.

The inheritance of a profession was specially an Egyptian custom.It cannot be purely accidental that the oldest of the long genealogies that we possess belongs to a family of artists; the members of this family evidently attached importance to the fact that such as the art described above, the art of rigid tradition — was hereditary in their family.

Individuality and Ordinary Life in Ancient Egyptian Art

Souren Melikian wrote in New York Times the remarkable show “Haremhab, the General Who Became King” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the summer of 2011"which zooms in on the time of Haremhab, the military chief who wielded immense power before ruling as a pharaoh from around 1316 to 1302 B.C.”dispels the long-held myth that ancient Egypt was a culture solely concerned with timeless icons of gods and kings in postures dictated by canon even if that is not the purpose of the show. Viewers discover that images of humans lost in their private thoughts and beset by anxiety already appeared in Egypt by the mid-third millennium B.C. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, May 20, 2011]

Among a few works serving as an introduction to Haremhab’s lifetime, the small figure of a scribe, probably from Saqqara in the area of ancient Memphis, is seen seated cross-legged, holding a papyrus scroll unrolled on his lap. The hieroglyphic inscription engraved on the scroll states his name, Nikare, and his title, scribe, one of the highest offices in the ancient Egyptian administration.

At first glance, the granite statue follows the canonical representation of the official who mastered the difficult art of hieroglyphs. On closer inspection, a personalized portrait can be made out. The man, no longer in his prime, is hunched, as if bending under the weight of his concerns. Light furrows come down from his nose. No smile lights up his face. Subtle as it may be, the suggestion of weariness is unmistakable in Nikare’s three-dimensional likeness.

About four centuries later, an artist carving scenes on the limestone walls of a funerary chamber in ancient Thebes, depicted another scribe with his reed brush stuck behind his ear. A tiny fragment, 10.9 by 9.2 centimeters, or 4 5/16 by 3 5/8 inches, is preserved, showing part of the head in profile. Excavated by a Metropolitan Museum team around 1911-12, it is believed to date from 2000 B.C., give or take 20 years. The tomb was that of a pharaoh’s vizir called Dagi who may have employed the scribe. The man stares glumly. His raised eyebrow suggests incredulity. If the sculptor meant to convey the shock of a man who has suddenly been made aware of his mortality, he could not have done it better.

At rare intervals, the private life of ancient Egyptians and the feelings that they experienced moved artists to stray away from the beaten path. An intriguing sculptural group of two men at different stages of life and a young boy at their side was probably carved during the reign of Akhenaten, the pharaoh who revolutionized Egyptian thinking by proclaiming that there is only one God, some time between 1349 and 1332 B.C. On the low reliefs that depict him, Akhenaten is seen with a smile of mystical illumination. But when looking at the father and son, the anonymous artist portrayed ordinary humans.The father, who stands in the middle, embraces his son in a protective gesture, with his hand coming down over the boy’s shoulder. A sense of harmonious intimacy emanates from the happy family scene.

But, even when they set out to portray the great and the good, the ancient Egyptian artists sometimes took note of the sitters’ frame of mind. Idealized as it is, the famous Metropolitan Museum’s statue of Haremhab as a scribe, carved when he was still a general, betrays a certain weariness: hardly surprising in a man who had a full hand — as the commander in chief of the Egyptian army, he organized campaigns against the Hittites in faraway Anatolia to the northeast and Nubia on the southern front.

Lesser characters were prone to be depicted in a more individualized fashion. The small granite figure of an unidentified scribe carved between 1295 and 1070 B.C. shows a man looking alert and concerned. Eyes wide open, with his eyebrows slightly raised, the scribe presses his lips as if he had just been given an admonition about his performance.

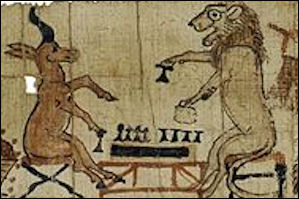

Humor, Sarcasm and Prejudice in Ancient Egyptian Art

“A strong sarcastic strain comes out here and there, mostly in very small pieces,” Souren Melikian wrote in New York Times. “The ancient Egyptians were not above expressing their dislike of foreigners. Warfare repeatedly pitched the pharaohs against the Semitic states of the Near East. The unknown artist who engraved an ivory plaque destined to adorn a piece of furniture clearly did not have much sympathy for the Assyrians.A prisoner wearing the Assyrian princely attire is depicted raising his arms, tied around the wrists. He seems to be wriggling in a curious quasi-dancing posture. The Assyrian’s goggle-eyed stare makes him a figure of fun. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, May 20, 2011]

“A strong sarcastic strain comes out here and there, mostly in very small pieces,” Souren Melikian wrote in New York Times. “The ancient Egyptians were not above expressing their dislike of foreigners. Warfare repeatedly pitched the pharaohs against the Semitic states of the Near East. The unknown artist who engraved an ivory plaque destined to adorn a piece of furniture clearly did not have much sympathy for the Assyrians.A prisoner wearing the Assyrian princely attire is depicted raising his arms, tied around the wrists. He seems to be wriggling in a curious quasi-dancing posture. The Assyrian’s goggle-eyed stare makes him a figure of fun. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, May 20, 2011]

Relations between the ancient Egyptians and the Nubians who lived south of their territory were not the best either. A small limestone trial piece was dug up at Tell el-Amarna by William Flinders Petrie during his 1891-92 excavation campaign. The sculpture in sunken relief portrays a man with curly hair and exaggerated protruding lips. This is a caricature, definitely not meant to flatter the model.

The museum label dates the small plaque to the reigns of Akhenaten or Tutankhamun, adding that it is “reminiscent of the images of Nubians and West Asians found in Haremhab’s tomb at Saqqara.” At that time Haremhab was still the commander of Tutankhamun’s army. Apparently, the dour general wasted no love on his foes. This was an ethnocentric culture that took an unfavorable view of outsiders.

It is only fair to add that the ancient Egyptians’ sense of fun could sometimes be turned on the sacred symbols of their own religion.Toth, the god of writing, accounting and other intellectual pursuits, was associated with two animals, the baboon and the ibis. A marvelous group on loan from the Louvre, which was carved under Amenhotep III (1389-49 B.C.), portrays the royal scribe Nebmerutef. The official reads a scroll with the faintest smile of concentrated attention. This is a man aware of his power to get things done. Perched on a pedestal next to him, a baboon with bushy eyebrows frowns, creating an irresistibly comical effect.

Artists retained their sense of fun right down to the end of ancient Egypt. A small turquoise faience baboon, 8.8 centimeters high, is a masterpiece of understated irony, so discreetly wielded that one cannot be absolutely sure that mockery was intended. Seated with its hands resting on its thighs and its penis delicately rendered, the animal stares ahead, with a suggestion of defiance and amusement all at once.

Their humor did not desert Egyptian masters when they portrayed themselves. A wooden statuette of Kery, who was active under Ramesses II (1304-1237 B.C.), hails him as the “great craftsman in the place of truth.” Kery was one of the artists chosen to decorate the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. The master proudly marches on, carrying the standard of “Horus son of Isis, Lord of the desert” on the staff. His happy expression suggests that his prayer for “a good life, combined with health, gladness and rejoicing every day” inscribed on the base had been fulfilled. With his puffed-up cheeks, the craftsman seems about to laugh, despite the solemn tone of his religious invocation that ends “my two eyes seeing, my two ears hearing, my mouth filled with truth.”

Portraits in Ancient Egyptian Art

Thutmose III

Dimitri Laboury of the University of Liège in Belgium wrote: “Ancient Egyptian art’s concern with individualized human representation has generated much debate among Egyptologists about the very existence of portraiture in Pharaonic society. The issue has often—if not always—been thought of in terms of opposition between portrait and ideal image, being a major topic in the broader question of realism and formal relation to reality in ancient Egyptian art. [Source: Dimitri Laboury, University of Liège, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The ideal image comprises many important and problematic issues of ancient Egyptian art history and of the history of the discipline. “Portrait” means a depiction, in any kind of medium, of a specific individual, i.e., an individualized representation of a recognizable person. As opposed to “ideal (or type) image,” portrait implies a pictorial individualization and relates to the notion of realism as an accurate and faithful rendering of objective reality, which stands in contrast to idealization. Even if it is traditionally accepted and used as a fundamental concept in art history as a whole, this key-opposition between realism and idealization (or idealism) is far from being unproblematic from a theoretical point of view.”

“As Sally-Ann Ashton and Donald Spanel have noted, portraiture in ancient Egyptian art “was limited almost exclusively to sculpture”; three- dimensional portraits allow more detailed and subtle rendering, and this is probably why they appear to have influenced two- dimensional representations, and not the reverse; in quantity, as well as in quality, royal iconography is much better documented than private portraiture and often impacted the latter; and finally, as the portrait of an individual and at the same time of an institution—the very central one in ancient Egyptian civilization.”

Thus, “Portraiture in ancient Egyptian art can be defined as a vectorial combination, a tension, or a dialectic between an analogical reference to visual perception of outer or phenomenological reality and a consciously managed departure from this perceptual reality, in order to create meaning or extra- meaning, beyond the simple reproduction of visual appearances and sometimes, if necessary, despite them. As such, portraiture is nothing but the application of the very essence of the ancient Egyptian image system to the individualized human representation.”

Ancient Egyptian View of Images and Identity

Dimitri, Laboury of the University of Liège in Belgium wrote: “The entire monumental culture of ancient Egypt manifests a profound desire to preserve individual identity, especially from a funerary perspective, and thus exhibits a rather strong self-awareness. In this sense, “Portraiture is by far the most important and productive genre of Egyptian art, just as biography is the most ancient and productive genre of Egyptian literature” . But, even with this fundamental principle of self- thematization—as Assmann proposes to characterize it—in order to validate the use of the notion of portrait, the two concepts that theoretically define it, i.e., individual identity and recognizability, have to be assessed in the context of ancient Egyptian art and thought. [Source: Dimitri, Laboury, University of Liège, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Queen Hatshephut as a sphinx

“As in many other civilizations, the word for image in the ancient Egyptian language, twt, implies the notion of likeness since it is related to a verbal root that means “resembling to, being like or in accord (with)”. Thus, the image is clearly conceived as a resembling pictorial transposition of its model. But the numerous usurpations of statues performed merely by the re-carving of the name and without any facial reshaping, the variability in the portraitures of a specific person (either royal or private), and the genealogies of some portraits, in which an individual iconographically and physiognomically associated himself or herself with a predecessor, demonstrate that the ancient Egyptian concept of resemblance was less constraining than in modern western cultures Assmann suggests defining this concept as a principle of non-confusability, i.e., a recognizability that could be fulfilled on multiple levels or just by the sole presence of the name of the depicted person. Furthermore, one cannot underestimate the metaphysical dimension of the concept of resembling image: what is it supposed to resemble? The physical and external—or phenomenological—appearance of its model or his or her actual reality, which could lie beyond appearances? Not to mention the close connection—and so perhaps some sort of permeability—that ancient Egyptian thought established between these two—very western—theoretical concepts of external appearance and inner reality, as is suggested by the customary complementarity between qd (“shape” or “external form”) and Xnw (“inside” or “interior”) and expressions that define inner or moral qualities by an outer description of the face, such as nfr-Hr, spd-Hr, etc.

“Just like “being Egyptian” was not primarily a question of ethnicity but of Egyptian-like or non-Egyptian-like behavior, the ancient Egyptian notion of individual identity appears to be fundamentally conceived as a personal behavioral or functional integration into the societal order. This is substantiated by the importance and persistence of comportment clichés in almost any kind of biographical texts. So, in other words, the individuality of a person with his or her own name, genealogy, and specific fate (SAy) is always defined within the social framework of ancient Egypt, i.e., according to social types or ideals, which shape and often overshadow or absorb the expression of uniqueness and singularity.

“In such a cultural context, the traditional pseudo-opposition or the dialectic portrait versus ideal image needs to be viewed and used as a vectorial combination (as suggested above) or as a tension, which structured and generated different forms of self- thematization, in representational arts as well as in literature.”

Representations of Pharaohs

In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, Pharaohs were represented as demigods, either as he stood making offerings before the gods of his country, or as he stabbed a prisoner, or seated conventionally on his throne under a canopy. During the New Kingdom artists emphasised in the pictures the Pharaoh’s human side. His wife and children are always around him even when he is driving to the temple or praying; they are by his side when he looks out of the window of his palace; they mix his wine for him as he rests on his seat. The children of the Pharaoh play together or with their mother, as if their divine origin were completely ignored. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The details of these pictures are still more remarkable. It is true that there may not have been much beauty in the royal family of Amenhotep, and the king and queen — who probably were brother and sister — may really have possessed consumptive faces and elongated necks, pointed elbows, fat bodies, thick ankles, and thin calves, but the artists who had to draw their figures need not have emphasised these unlovely peculiarities as so many of them have done. There was a happy medium between the old conventional royal pictures and these caricatures; it was a fatal misfortune that most of Chucn'ctcn's artists failed to find it.

They often overshot their mark also with regard to the positions in which they represented their figures. It was not necessary to represent individual figures in rapid movement without any reasonable cause, nor to make their limbs move in wavy lines. In the same way it was not necessary to represent the king and queen seated so close to each other, that the outlines of their figures are almost identical, and. it is only from the arms, which are placed round each other, that we can understand the meaning of the picture.

Immense Ancient Egyptian Battle Reliefs

Immense battle reliefs emerged during the middle of the New Kingdom and originated to celebrate the victories of Seti I. The composition in all is alike. At the side of the picture stands the gigantic form of the Pharaoh, on his chariot of war drawn by his prancing steeds. Before him is a wild confusion of little figures, fugitives, wounded men, horses that have broken loose, and smashed chariots, amongst which the monarch flings forth his arrows. Behind, on a hill, stands the fortress close to which the battle takes place. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The effect of this picture lies undeniably in the contrast between the powerful form of the victor, represented by the artist in all the splendour he could command, and the confused crowd of the conquered foe. The calm attitude of the Pharaoh by the side of the rapid movement of the enemy, illustrates in, I might almost say, an ingenious way, the irresistible power of the king, who drives the crowd of his feeble enemies before him as a hawk drives a swarm of sparrows.

Ramses II gave the artists who had to perpetuate his deeds a yet harder task to perform. They had not only to show in halfsymbolic manner the king and his foes, but faithfully and historically to portray for posterity special events in real battles. We cannot be surprised that the execution of these pictures is far behind the conception. Many details are however quite worthy of our admiration — for instance, there is a dying horse which is excellently drawn y a representation of camp-life that is full of humour, but there is no attempt at unity of composition. Again and again we may see soldiers marching and soldiers formed in square, enemies who have been shot and enemies drowning, chariots attacking and chariots at rest, yet no uniform picture. The fine contrast also between the Pharaoh storming forward, and the king of the Hittites hesitating in the midst of his troops, which occurs in the most extensive of these pictures,'' does not impress us much in the midst of all this confusion of detail.

Reuse and Restoration in Ancient Egyptian Art

Peter Brand of the University of Memphis wrote: “Like members of all pre-modern societies, ancient Egyptians practiced various forms of recycling. The reuse of building materials by rulers is attested throughout Egyptian history and was motivated by ideological and economic concerns. Reuse of masonry from the dilapidated monuments of royal predecessors may have given legitimacy to newer constructions, but in some cases, economic considerations or even antipathy towards an earlier ruler were the decisive factors. Private individuals also made use of the tombs and burial equipment of others—often illicitly— and tomb robbing was a common phenomenon. Ultimately, many monuments were reused in the post-Pharaonic era, including tombs. Restoration of decayed or damaged monuments was a pious aspiration of some rulers. In the wake of Akhenaten’s iconoclastic vendetta against the god Amun and the Theban triad, his successors carried out a large-scale program of restoring vandalized reliefs and inscriptions. Restorations of Tutankhamun and Aye were often usurped by Horemheb and Sety I as part of the damnatio memoriae of the Amarna-era pharaohs. Post-Amarna restorations were sometimes marked by a formulaic inscribed “label.” Restoration inscriptions and physical repairs to damaged reliefs and buildings were also made by the Ptolemaic kings and Roman emperors. [Source: Peter Brand, University of Memphis, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In ancient Egyptian society, as in all pre-modern societies, goods and materials were scare and valuable, and thus frequently recycled. Raw materials were expensive due to their relative scarcity (wood, metals, and semi-precious stones, being examples) or to the intense labor and expenditure of materials needed to obtain them, such as that required by the quarrying and transport of all types of stone, and metals. Spent, non-consumable goods were not simply disposed of when broken or obsolete if it was possible to harvest useful raw materials from them. The practice of recycling is attested in the archaeological record and in textual sources. Among the latter are the timber accounts from Memphis from the reign of Sety I. These constitute a city-wide inventory of wood, much of it old ship-parts, found in the possession of various officials. They attest to the value of timber as it was perceived by both the officials who collected it for their own use and by the royal administration, which saw it as a source of taxation. Even papyrus was recycled when texts written upon it became obsolete.

“The most intensively reused substances were metals, all of which were highly expensive and could be melted down and recast to make new objects. Metals were carefully weighed and their use and reuse tracked in administrative documents; the copper chisels used by the tomb workers from Deir el-Medina, for example, were collected and weighed for recasting once they had broken. The illicit recycling of precious metals is attested from sources such as the late Ramesside tomb- robbery papyri.”

See Separate Article: REUSE AND USURPATION IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ART africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024