Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

SEX IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Egyptians believed that radishes were aphrodisiacs. Lettuce has been described a the Viagra of the Egyptian era. The sexual genitalia of animals was believed to promote youth and sexual vigor. Body paste and facial creams were made of calf penises and vulvas. Men and women shown embracing on tomb murals and the like were regarded as married or having sexual relations and there was an understanding their erotic life would continue in the afterlife.

Egyptians believed that radishes were aphrodisiacs. Lettuce has been described a the Viagra of the Egyptian era. The sexual genitalia of animals was believed to promote youth and sexual vigor. Body paste and facial creams were made of calf penises and vulvas. Men and women shown embracing on tomb murals and the like were regarded as married or having sexual relations and there was an understanding their erotic life would continue in the afterlife.

The ancient Egyptians performed circumcisions and had an initiation ritual after it was done and had erotic dancing. There are some references to fetishism and masochism in Egyptian writings. Nose kissing appears to have been popular. In some reliefs Ramses II is pictured with a big dick and strong erection.

The earliest known prescriptions for contraceptives came from Egypt (between 2000 and 1000 B.C.) and were written on papyrus scrolls. To keep from having babies, Egyptian women were advised to inset a mixture of honey and crocodile dung in their vagina. The honey may have acted as a temporary cervical cap but the most effective agent was acid in the dung that acted as the world's first spermicide. Methods of birth control mentioned in the Petri Papyrus (1850 B.C.) and Eber Papyrus (1550 B.C.) included coitus interruptus and coitus obstructus (ejaculating into a bladder inserted in a depression at the base of urethra).

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “Bodily associations also permeate the realm of objects and images used in offering rituals. Model phalli and vulvae are attested as votive offerings, as are figurines of naked women and nursing women. Censers were made in the form of a human hand and offering tables could have pouring spouts in the shape of the glans penis. The action of pouring an offering (stj; water and water- related determinatives) is homologous with the word used for both ejaculation and impregnation (stj; phallus determinative), setting up a punning relationship between the body and the bodily act of prayerful libations. This link between sexuality and religious practice underscores the important role the body played in constructions of gender and sexual relations (see Hare 1999: 106 - 124; Meskell and Joyce 2003: 95 - 119).” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: The Egyptians were the first who made it a point of religion not to lie with women in temples, nor to enter into temples after going away from women without first bathing: for almost all other men except the Egyptians and the Hellenes lie with women in temples and enter into a temple after going away from women without bathing, since they hold that there is no difference in this respect between men and beasts: for they say that they see beasts and the various kinds of birds coupling together both in the temples and in the sacred enclosures of the gods; if then this were not pleasing to the god, the beasts would not do so. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Erotica: The Essence of Ancient Egyptian Erotica in Art and Literature”

by Joseph Toledano El-Qhamid, et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“Sex and Gender in Ancient Egypt: 'Don Your Wig for a Joyful Hour'

by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2008) Amazon.com;

“Sacred Sexuality in Ancient Egypt: The Erotic Secrets of the Forbidden Papyri”

by Ruth Schumann Antelme , Stéphane Rossini, et al. (2001) Amazon.com;

“Sex and the Golden Goddess I: Ancient Egyptian Love Songs in Context”

by Renata Landgráfová and Hana Navratilova (2010) Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“Sacred Luxuries: Fragrance, Aromatherapy, and Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt”

by Lise Manniche and Werner Forman (1999) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ceremonies of Love Wedding Traditions in Ancient Egypt” by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“Love Poetry and Songs from the Ancient Egyptians” by Gilbert Moore (2015)

Amazon.com;

“Blood Is Thicker Than Water’ – Non-Royal Consanguineous Marriage in Ancient Egypt: An Exploration of Economic and Biological Outcomes” by Joanne-Marie Robinson (2020) Amazon.com;

“An Incestuous and Close-Kin Marriage in Ancient Egypt and Persia: Examination of the Evidence” by Paul John Frandsen (2009) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Circumcision in Ancient Egypt

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “Although most of the mummies thought to be those of kings were not circumcised, male circumcision was practiced (probably around the onset of puberty) to some extent. There is no clear evidence for female circumcision (excision) during the Pharaonic Period, though there may be some indications for the practice, in particular from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. Male circumcision was one of a number of practices related to priestly service, all of which were concerned with purity. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

The Offering of Uha, (c. 2400 B.C.) contains a passage related to male and female circumcision in Egypt. It reads: “An offering which the king and Anubis, Who is Upon His Mountain, He Who is in Ut, the Lord of the Holy Land, give: An invocation-offering to the Count, Seal-Bearer of the King of Rekhyt [Lower Egypt], Sole Companion, and Lector Priest, honored with the great god, the Lord of Heaven, Uha, who says: I was one beloved of his father, favored of his mother, whom his brothers and sisters loved. When I was circumcised, together with one hundred and twenty men, and one hundred and twenty women, there was none thereof who hit out, there was none thereof who was hit, there was none thereof who scratched, there was none thereof who was scratched. I was a commoner of repute, who lived on his own property, plowed with his own span of oxen, and sailed in his own ship, and not through that which I had found in the possession of my father, honored Uha.” [Source: D. Dunham, Naga-ed-Der Stelae of the First Intermediate Period, (London, 1917), pp. 102-104, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University].

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: the Colchians, Egyptians, and Ethiopians alone of all the races of men have practised circumcision from the first. The Phoenicians and the Syrians who dwell in Palestine confess themselves that they have learnt it from the Egyptians, and the Syrians about the river Thermodon and the river Parthenios, and the Macronians, who are their neighbors, say that they have learnt it lately from the Colchians. These are the only races of men who practise circumcision, and these evidently practise it in the same manner as the Egyptians. Of the Egyptians themselves however and the Ethiopians, I am not able to say which learnt from the other, for undoubtedly it is a most ancient custom; but that the other nations learnt it by intercourse with the Egyptians, this among others is to me a strong proof, namely that those of the Phoenicians who have intercourse with Hellas cease to follow the example of the Egyptians in this matter, and do not circumcise their children. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Ancient Egyptian Gods and Sex

Nut was the sky-goddess. She was the great mother who held up the canopy of the sky. From her breast poured the Milky Way. In one tomb painting she is shown with her legs spread and her lover Geb, with an erect penis, reaching for her. Pharaohs often claimed to be the offspring of Nut and Geb, or as Pepi II put it from "between the thighs of Nut." In the Heliopolitan creation myth, Atum was considered to be the first god, having created himself, sitting on a mound from the primordial waters. Early myths state that Atum created the god Shu and goddess Tefnut by spitting them out of his mouth after masturbating, with his hand representing the female principle inherent within him.

Min, the god of sexual fertility, appeared in both human form and as an erect phallus. It was no surprise that he was worshiped by a fetish cult similar to the one that honored Dionysus (Bacchus) in Greece. Closely associated with Amun, he was originally the primeval god of Coptos and was represented as an ithyphallic human statue, holding a flagellum. Geb was the Earth god. He is sometimes depicted with an erect penis and was sometimes represented by a crocodile.

According to legend Osiris was originally a local fertility god in southern Egypt. He was slain by his evil brother Seth and had his body parts scattered all over the world. In one version of the story his body was torn into 14 pieces and all of them were found except one piece — Osiris’s penis.

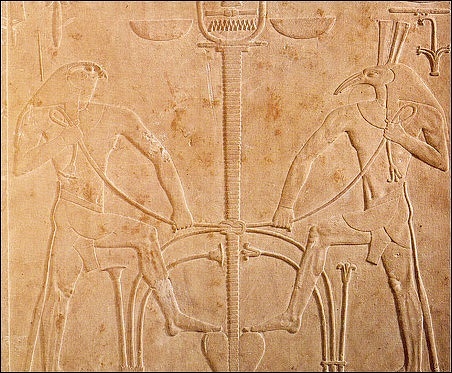

Confrontation Between Seth and Horus and Their Sperm

Seth and Horus

“One evening, as the gods Seth and Horus lay together resting, Seth inserted his penis between the thighs of Horus. Horus, however, unknown to the Dark Lord of Storm, had caught Seth's semen in His hand. With the help of His mother, Isis, He placed His own semen upon lettuce growing in a garden; lettuce that Seth was to eat. Seth spake unto Horus, "Come, let us go, that I may contend with you in the Court." Within the Court, Seth declared, "Let the office of Ruler be given to Me, for as regards Horus who stands here, I have done a man's deed to Him." [Source: Theology WebSite]

“Horus laughed and said, "What Seth has said is false. Let the semen of Seth be called, and let us see from where it will answer."And so Thoth, the Self Created, called upon the semen of Seth. The answer came from a far-away marsh, where Isis had long since deposited it. Horus said, "Let mind be called, and let us see from where it will answer." Then Thoth laid His hand on the arm of Seth and said, "Come out, semen of Horus!" And it spake unto Him, "Where shall I come out?" Thoth said to it, "Come out of His ear." It replied to Him, "Should I come out of His ear, I who am Divine Seed?" Then it came out as a Golden Sun Disk upon the head of Seth. Seth became very angry, and He stretched forth His hand to seize the Golden Disk. In desperation, Seth demanded one more contest with Horus. Before the whole Ennead he declared, "Let both of us build a ship of stone. We shall race them down the Nile. Who-so-ever wins the race shall wear the Crown of Osiris." Horus agreed to the contest at once.

Pornography and Adultery in Ancient Egypt

A series of pornographic pictures, drawn and annotated by a caricaturist were found in the 20th Dynasty tomb, indicating that even the deceased were supplied with such literature for the eternal journey. There is also an ancient sacred book describing the life of the deceased Pharaoh in bliss, assuring him, with the addition of some words we cannot quite understand, that in heaven he will “at his pleasure take the wives away from their husbands. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Egyptian gender categories seem rigid....the genitals of elite males are always hidden, although the pubic triangle of elite women is often outlined under their clothing. Moers stresses the social power of the representations of the normative, elegant, well-ordered body in visual and written media: feelings of shame are attributed to people when they fail to conform to this image, such as the young woman in the love poems who worries that “people” will describe her as “one fallen through love” because, distracted by daydreams of her beloved, her heart beats violently and she is neglecting her appearance. Moers also makes the interesting argument that this socially constructed normative body is male: women would always be considered slightly at a disadvantage.” [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “In ancient Egypt, villages were insular and quite xenophobic, and adulterous relationships were seen as threatening the family alliances within the village. The Egyptians considered both males and females as responsible for adultery. Egyptian literary texts suggested that the punishment for adultery for both parties was death at the hands of the betrayed party. However, there is little evidence that this punishment was used, and legal texts suggested that the usual punishment for a guilty male was some form of fine and for the woman most likely a divorce. It is unclear (but it is unlikely) whether an aggrieved wife could divorce an adulterous husband. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Ancient Egyptian Love

_and_queen.jpg)

King Menkaura and queen Her hair lapis lazuli in its glitter.

The hieroglyphic for "love" consists of a hoe, a moth and a man with a hand in his mouth. It literally meant "to want, choose, or desire." Lovers in poems often address each other as brother or sister.

Archaeologists have found 55 anonymous love poems, dated around 1300 B.C., on papyri and vases. One of them goes:

” More lovely than all other womanhood.

luminous perfect.

A star coming over the sky-line at new year.

a good year.

Splendid in colors.

with an allure in the eye's turn.

Her lips are enchantment.

her neck the right length.

and her breasts a marvel;

her arms more splendid that gold.

Her fingers make me see petals.

the lotus' are like that.

Her flanks are modeled as should be.

her legs beyond all other beauty.

Nobel her walking

My heart would be a slave should she enfold me. “

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN POEMS: LIMERICKS, LOVE AND SAME SEX LOVE africame.factsanddetails.com

Sekhemka and Henutsen — Together Forever

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: During excavations at the necropolis of Abusir, Egyptologists discovered an unusual funerary monument embedded in an Old Kingdom mudbrick mastaba tomb dating to the 4th Dynasty (ca. 2575–2465 B.C.). The recently uncovered stela, however, dates to the first half of the 5th Dynasty (ca. 2465–2323 B.C.) and memorializes a scribe of the treasury named Sekhemka and his wife Henutsen. “Sekhemka was probably a rather low-level official and died much younger than expected,” says Egyptologist Martin Odler of Charles University. This may be why an older tomb was reused. [Source:Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

The white limestone stela is 3. 5 feet tall and 1. 5 feet wide and depicts the couple standing in a doorway. In a relief atop the doorway, the pair is seated at an offering table covered with 12 loaves of bread. Hieroglyphic inscriptions around the table indicate that Sekhemka and Henutsen should fare well in the afterlife. These inscriptions suggest they would ideally be buried with lighted incense, 1,000 pieces of alabaster, 1,000 pieces of linen, 1,000 loaves of bread, and 1,000 jars of beer, as well as seven sacred oils, including the “best cedar oil” and other, less easily identifiable substances such as “festive oil. ”

The offering scene, doorway, and hieroglyphs surrounding the figures were all once painted in rich shades of red, yellow, blue, green, and black. A surprising amount of the pigment survives. Aside from the rarity of preserved paint, Odler explains that the stela is significant because it combines well-known elements of funerary monuments in a completely unique way. “The stela shows that our knowledge of the Old Kingdom is limited,” he says. “We can still find unexpected artifacts that make Old Kingdom Egyptians more human and more creative than expected. ”

Gender in Ancient Egypt

Pharaoh and Queen Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Masculinity, femininity, and possibly other (intersexual) genders in ancient Egypt were expressed in, and simultaneously shaped by, many different contexts, such as material culture, artistic representation, burial equipment, texts, and the use of space. Ideally, gender should be investigated in combination with other factors, such as social standing, ethnicity and/or age, focusing on specific periods, places, professions, and/or social settings to avoid over- generalization. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Meskell has argued that we should not separate sex from gender since the Egyptians did not. In many cases the two coincide: the representation of men and women in two or three dimensions is strongly gender-bound, with conventions of skin coloring, body posture, hairstyle, and clothing used to differentiate between women and men. However, although we should study Egyptian categories, we, today, are not necessarily bound by them.

“Gender never operates in isolation, but overlaps with many other factors, such as social standing, age, ethnic background, and so on. Egyptologists have tended to investigate these intersecting factors by looking at specific groups of men or, usually, women, who have a common social background or similar status.

“Alternatively, one might approach the intersection of gender and other factors such as ethnicity, social standing, or age, by investigating how the representation of gender is affected by the context of representation, the intended audience, or the specific topic under discussion. For example, at times in monumental records, the enemies of Egypt are “othered” to an even greater degree by inverting their gender, so that enemy males are represented in female terms. For instance, Ramesses III is said to look upon the Nubian bowmen as Hmwt (women). However, this gender inversion is applied in varying degrees depending on the Egyptians’ attitudes to that particular enemy, so that the Libyans tended to be feminized to a greater degree than, say, the Hittites or the Mitannians. The feminization of Egypt’s enemies in this way is also restricted specifically to royal contexts: it is not a normal feature of the contacts of other Egyptians with foreigners. In his role as Egypt’s defender, the semi-divine king is hyper-masculinized: the conventions of decorum that would be appropriate for other men do not apply to him.”

Duality and Gender Construction in Ancient Egypt

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “The Egyptians often classified in dualities. Dualities are highly problematic for much current feminist thought, because a binary way of thinking often leads to the exaltation of one category at the other’s expense; alternatives might be to regard the categories as fuzzy-boundaried rather than rigid, to set up multiple categories, to think in terms of “both/and”, or to regard the dualities as part of a complementary whole; for instance, Troy has shown that kingship in ancient Egypt was an androgynous concept where both king and queen played essential and complementary roles. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“For the Egyptians, however, dualities might be opposed, but were ultimately to be reconciled; for instance, the king unites Horus and Seth, deriving his power from the fusion of justice and loyalty with wildness. Troy, moreover, argues that the polarity of Seth’s ultra-masculinity is presented negatively as unfruitful, whereas Osiris, a male god with female aspects, and Isis, a goddess with masculine aspects, ultimately have a fruitful partnership.

“Notable examples of gender construction in Egypt are the female kings Neferusobek and Hatshsepsut, who had to negotiate between their female sex and their kingship, which was socially defined as male. Neferusobek was sometimes represented wearing a royal kilt and nemes-headdress over a dress. Although early in her rule, Hatshepsut was represented with a combination of male and female elements, she rapidly adopted the image of a male king, whereas in the texts that accompany her male images, she is often described with female nouns and pronouns. On the other hand, Robins (1999) has demonstrated how Hatshepsut’s kingly titulary capitalizes upon her female sex to build identifications with goddesses that would have been impossible for male kings.

Gender Concepts Expressed in Ancient Egyptian Material Culture

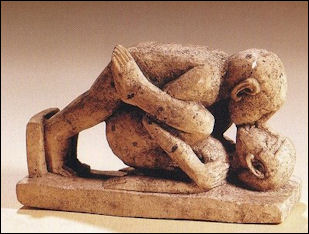

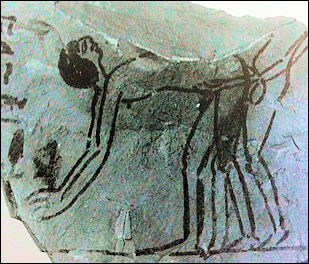

from the Book of the Dead, looks like oral sex but actually a form of worship

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Gender is often expressed via, and simultaneously shaped by, material culture. Smith’s study of ethnicity in Nubia (2003) is an excellent example, because the way ethnicity is played out in material culture often involves gender- associated artifacts. From the presence of Nubian domestic cookpots and Nubian fertility figurines in household shrines at the fortress of Askut, both of which tended to be associated with women in Egyptian culture, Smith suggests that during the Second Intermediate Period the Egyptians living in the fortresses were marrying local women, who maintained their ethnic identity, among other things, via Nubian foodways. On the other hand, the (male) commander of the fortress, who would have entertained (male) emissaries sent by the ruler of Kerma and other Nubian dignitaries, used elegant Nubian serving vessels to honor his guests, so that interpretive issues pertaining to ceramics, gender, and ethnicity intersected differently in different social settings. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Places where certain people might be admitted and others not, or where certain people would find it easier to go than others, also shaped various aspects of identity in ancient Egypt, such as status, membership in or exclusion from a given group, and sometimes gender. Domestic space, shared by both sexes on relatively equal terms of status, may have been particularly important for the expression and shaping of gender. Meskell argues that in the tomb-builders’ village of Deir el-Medina, the first room of the house, often equipped with a domestic altar, was associated with a domestic cult strongly associated with fertility and female themes, whereas the more imposing second room with divan and emplacements for stelae was associated with male activities, including socializing on the weekends. Meskell’s views have been somewhat simplified elsewhere, and it is important to retain her original nuances: the second room was also used by women, particularly during the week when the men were away at work; men could also have participated in cultic activities in the first room; and the first room could also have been used for everyday activities such as spinning or food preparation. On the other hand, Kleinke has argued convincingly that use of the rooms cannot have been restricted to one sex or the other and points out that the domestic ancestor cult and fertility were concerns of both sexes. Similarly, Koltsida makes an excellent case for the use, by both men and women, of the second room in Deir el- Medina houses. We could thus envisage domestic spaces and areas that were associated more with one sex but did not exclude the other, or were the focus of special activities by one sex but where other activities by both sexes also took place.

“Both women and men underwent the same journey through the afterworld and the same judgement at the end, and people were integrated into the community of Osiris regardless of gender. However, McCarthy and Cooney point out that certain aspects of the entrance to the afterlife, such as having intercourse with the Goddess of the West in order to be reborn from her in the next world, required the dead person to be male. Lacking a penis, women might have had difficulty with this aspect of regeneration. McCarthy suggests that Queen Nefertari is represented in her tomb undergoing a fragmentation of her gender identity at death, which allowed her to be identified with Osiris and Ra in order to be regenerated.

“Similar arguments are made by Cooney for women in general in the New Kingdom. Cooney demonstrates how this redefinition of women’s gender on entering the afterlife was reflected in the gender- neutral or masculine representation of women in certain kinds of burial equipment, such as (most) shabtis and coffins. Once she had successfully passed the judgement of the dead, a woman would attain the status of akh (glorified spirit), and would thus be depicted as a woman, adoring the gods of the afterworld and enjoying the pleasures of the blessed realm. By contrast, during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, deceased women were identified with the goddess Hathor, and their coffins represented them explicitly as female.

“On the other hand, inequalities from this world could also be perpetuated in the tomb. Meskell’s work on burials at Deir el-Medina shows that in this community, elite women’s burial goods were often fewer and cheaper than those of their husbands; this tendency increased in proportion to the couple’s status, whereas poorer couples had relatively egalitarian simple burials (possibly, I suggest, because the woman was generating proportionally more of the household income by weaving cloth). By combining material about both genders with status, this third-wave style analysis gives a richer and more nuanced picture than the enumeration of women’s burial equipment alone would have done.

Masculinity in Ancient Egypt

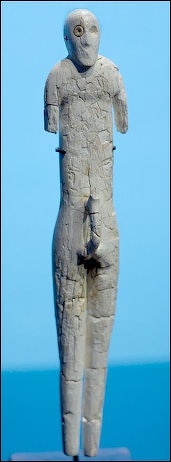

Pre-Pyramids Naqada culture figure

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “The study of masculinity involves analyzing how different sectors of society promote certain ideals of “what it is to be a man,” but also how people live with these ideals, conforming to them, resisting them, or adapting them. In Egypt, different masculinities emerge for different social groups and people: “being a (real) man” would have had different implications to some extent for a soldier, for a scribe working in a government department, and for a tomb- builder at Deir el-Medina. Appropriate male behavior would also have been tailored to the interpersonal context (towards one’s superiors, subordinates, or peers, at home with one’s family, towards women, when addressing the gods, and so on). [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The masculinity of the king was especially heightened, and it differed to some extent from that of his male subjects. For instance, Englund notes that while ordinary people were normally supposed to avoid the unruly behavior associated with Seth, the king was supposed to integrate the powers of both Horus and Seth. Royal masculinity was strongly adversarial, opposing the enemies of Egypt as manifestations of the chaos that threatened to engulf the created world . Yet the king could also be portrayed as lovable, even affectionate; dominance and grace were both essential elements of his rule.

“In a recent ground-breaking article, Parkinson outlines key features of elite masculinity in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), which includes elements of dominance (including the assertion of sexual potency), competition, and self-valorization for the admiration of other elite males. Peer rivalry was probably a fact of bureaucratic life. Examples include Papyrus Anastasi VI, where one official appropriated the weavers working for another just as the latter had finished his official quota of cloth, thus depriving him of his personal profit but creating a situation where the authorities were unlikely to intervene; or the mayors of Eastern and Western Thebes under Ramesses IX, who turned an inquiry into tomb-robbing in Western Thebes into a personal power struggle. On the other hand, normative texts such as the wisdom teachings helped shape the professional approach of scribes—a hierarchical one, aimed at gaining the favor of superiors and at times (as in the Satire of the Trades) looking down on subordinates and craftsmen.

“Masculinity for the inner elite, and the sub- elite scribes and administrators who surrounded them, can be traced in more general terms through the prescriptions of the wisdom teachings, which are primarily addressed to men; the (male) addressee is advised how to behave towards women (one’s wife, one’s colleagues’ wives, women in general) and a context of bureaucratic activity is supposed, which is again a male setting. On the other hand, norms such as acting according to maat plainly applied to men beyond the elite, and to both sexes, as did ideals such as looking after one’s aged parents. For example, the woman Naunakht, at Deir el-Medina, plainly expected her daughters as well as her sons to aid her in her old age and disinherited her offspring—both male and female—when they failed to do so.

“Even within a specific social setting, masculinity was not necessarily understood in the same way or expressed to the same extent by everyone: Parkinson highlights that the misuse of aggression was debated, that the boundaries between homosocial friendship and homoerotic attachment were ambiguous, and that other “ways of being masculine” beyond potency and dominance were also available to men in ancient Egypt.

Femininity in Ancient Egypt

Naqada female

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Femininity tended to be represented in terms of a woman’s role as her husband’s spouse and support, and mother of his children. Since the early 1990s Egyptologists have stressed the hegemonic yet partial nature of this representation. Religious and business activities undertaken by women can be traced by careful reading of the textual material, archaeological record, and representational material. Insights from gender archaeology, especially task distribution, can be very useful here. For instance, Wegner has used the distribution patterns of women’s seal impressions at the Middle Kingdom town of Abydos to demonstrate the scope of their sealing practices as mayor’s wife, female head- of-household (nbt-pr), or domestic administrator (jrjt-at) in and around various buildings in the town. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“On the other hand, many of the salient themes of masculinity (status, rivalry) are extremely difficult to find in material about women due to the partial nature of the record—for instance, Egyptian literary texts rarely represent women speaking to one another, which is clearly counterfactual. By contrast, women from the Egyptian royal house are relatively well known through the monumental record and their burials, even though their lives were atypical for Egyptian women and strongly imprinted by the ideology of kingship. Recent work on Egyptian queenship has highlighted the role of the women who were closest to the king. This particular form of femininity was far more closely integrated with the role of spouse than any other: it is almost impossible to imagine an Egyptian queen without a king. Even as queen regent for a minor son, the queen nonetheless stood in relation to the king.

“Queenship also had a far more heightened connection to deity than other forms of femininity. Ideologically, the queens fulfilled the role of various goddesses who nourished and supported the sun god, with whom the king was equated: the daughter who defended him, and the consort who regenerated him by giving birth to him after making love with him. If queens were represented in temple reliefs, they were normally depicted playing a supportive role, accompanying the king when he made offerings and chanting and playing the sistrum to appease the deity. During the Amarna Period, however, queens took a more active part: Nefertiti is represented offering sacrifices in her own right. The Hwt-bnbn, one of the temples Akhenaten built at Karnak in the early years of his reign, features Nefertiti alone making offerings, without any remembrance of Akhenaten. During Akhenaten’s reign, and that of his father, Amenhotep III, the chief queens adopted certain features of the masculine aspects of royal iconography: for instance, both Tiy and Nefertiti are represented attacking and subduing the female enemies of Egypt.

Homosexuality in Ancient Egypt

There are few references to homosexuality in Egyptian writing and art. In The “ Egyptian Book of the Dead” there is one passage in which a deceased man said he had sex with a boy. There are some reference to homosexuality in myths of certain gods, with the suggestion it was not normal and certainly was not as accepted as it was in ancient Greece.

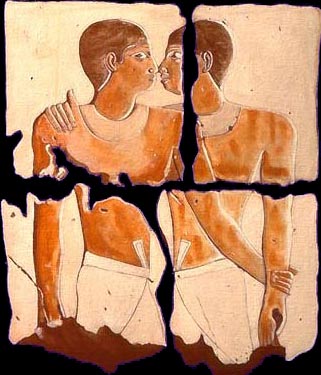

In 1964, an unusual image of two men embracing in a tomb for two men — Nianhkhnum and Khnumhotep — was found in the necropolis of Saqqara. Most scholars think the two men were twins. Some think they may have been Siamese twins. Others think they were gay. Evidence for the latter includes the fact that it was rare for men to be buried like this (most individuals were buried with the spouses and families) and other scenes show them holding hands and nose-kissing.

Nianhkhnum and Khnumhotep were chief manicurists for the pharaoh — relatively high status jobs — sometime between 2380 and 2320 B.C. Greg Reeder, an independent scholar, is one of the leading advocates of the belief they were gay. He told the New York Times that in the image in which they are embracing: “they are so close together that not only are they face to face and nose to nose, but so sloe that the knots of their belts are touching, linking their lower torsos. If fthis scene were composed of a male-female couple instead of the same-sex couple we have her there would be little question concerning what it is we are seeing.”

John Baines at Oxford University thinks the twin explanation is best. He told the New York Times, “The gay-couple idea is essentially derived from imposing modern pre-occupations on ancient materials and not attending to the cultural context.”

Looking for Evidence of Homosexuality in Ancient Greece

Nianhkhnum and Khnumhotep The Book of Ani, or the Egyptian Book of the Dead, contains passages related

homosexual activity is the "Negative Confession" — the judgement after death. Search for "lain with men". The Contendings of Horus and Seth — which describes the struggle between the two gods after Seth murderer Horus's father Osiris — has distinct homosexual overtones-based on who was dominating whom. The Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep may house the remains of earliest homosexual couple known to history. The A.D. 6th century Coptic Spell — For a Man to Obtain a Male Lover, Egypt — may have its roots in ancient Egypt.

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Probably some people in ancient Egypt engaged in same-sex sexual acts, and some may have preferred same-sex partners. Parkinson argues, however, that sexual preferences were not used to categorize people in ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, given the overwhelming heterosexual consensus, and the importance for a man to produce an heir, same-sex sexual behavior tended to be depicted as irregular and antisocial; allegations of being the passive partner in same-sex relations were used as an insult, as in the boundary stela erected by Senusret III at the fortress of Semna, where Egypt’s Nubian enemies are categorized as “back- turners.” [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Same-sex couples are difficult to trace, though this possibility has been suggested for various same-sex pairs buried together or sharing a stela. Depictions in the 5th Dynasty tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep show the two men with iconography similar to that of a married couple—iconography that has been variously interpreted as that of a same-sex couple, a pair of twins, and Siamese twins. Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep’s iconography is extreme, since they are depicted kissing, which is unusual at that period; even Old Kingdom scenes of king and goddess embracing represent them with lips not quite touching. Although tomb depictions show that both Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep had wives and children, the ample textual material provided in the tomb does not mention that they are brothers or name their parents, which might point in the direction of their being a couple.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN POEMS: LIMERICKS, LOVE AND SAME SEX LOVE africame.factsanddetails.com

Intersex Individuals in Ancient Egypt

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “The Egyptians were aware that beings might be both male and female, such as deities described as both father and mother. In texts from the temple of Esna, Neith is said to be 2/3 male and 1/3 female. In the creation narrative from the same temple, she gives birth to the god Ra. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The creator god was believed to have produced the first sexually differentiated pair of gods, by either spitting or masturbating; the hand with which he masturbated can be hypostatized as feminine, but he is not said to have a womb; his hand or his mouth, depending on the version of the story, functions as a magical substitute for a womb. The goddess Mut is occasionally portrayed in Book of the Dead vignettes with a phallus as a sign of power, possibly regenerative power, given the mortuary context. A faience statuette of Thoth from the sixth century B.C. represents him with an ibis head and female body, which prompts Stadler to identify him as a creator god, although there is a faint possibility that it might represent an ibis-headed goddess. Hapi, god of the inundation, has been thought to be androgynous, due to his breasts, penis sheath, and protruding (pregnant?) stomach, but Baines has shown that Hapi’s iconography is derived from representations of stout, successful officials and connotes maturity, not androgyny.

“Texts occasionally mention intermediate human categories between male and female. The execration texts (lists of the enemies of Egypt on bowls and figurines, ritually broken to neutralize the enemies’ power) mention “all people (rmTw), all the elite (pat), all the commoners (rxyt), all the men (TAy), all the sxtjw, all the women (Hmwt)….” This juxtaposition might suggest that sxtjw were a third sex, but Vittmann notes that the term sxtj is also used in the Pyramid Texts, in reference to Seth, who was castrated. Castrates are certainly attested at various points, the clearest example being the unpublished Demotic narrative Papyrus Carlsberg 448.2, in which someone was taken to the doctor and castrated in order to become “a man of the (royal) bedchamber”. Depauw and Vittmann have also noted persons of intermediate category who are depicted as female or determined as female—that is, textually, with the hieroglyphic determinative for “woman”—but are referred to with male pronouns and described as aor (castrate) or aHAwtj sHmt (literally “man-woman”), although some might be transgender, rather than transsexual, people. One might argue that the sxtjw could be a social category rather than a sexual one, listed here because of their special closeness to the king, but the juxtaposition of sxtjw, between men and women rather than associated with pat and rxyt, is probably significant.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024