Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

BEAUTY IN ANCIENT EGYPT

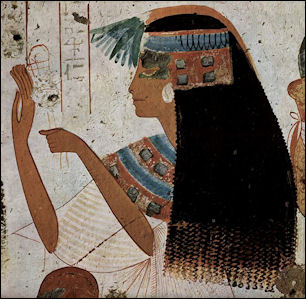

modern painting of an Ancient

Egyptian woman applying cosmetics Egyptians appeared to care a great deal about the way they looked. Pharaohs had their own hairdressers and manicurists and cosmetics was big business. Archaeologists have unearthed mirrors, hairpins, make up containers, brushes and other items. Egyptians took a lot of cosmetics and beauty aids with them to the grave which is why we have so much of the stuff today. Apparently they wanted to look good in the afterlife.

Cosmetic surgery was present. The Papyrus Ebers provided tips on fixing up noses, ears and other body parts disfigured by warfare or accidents. Childhood skull shaping was practiced by Egyptians as it was by Minoans, ancient Britons, Mayas and New Guinean tribes. A number of anti-wrinkle remedies were available.

Make-up was applied daily to statues of gods along with offerings of food. Sometimes people painted their entire face green or black to resembled the protective eye of the god Horus. On special occasions ancient Egyptians wore greasy cones of fragrance on their head that melted in the heat and dripped perfume on their wigs.

Alastair Sooke wrote for the BBC: “Ancient Egyptians of both sexes apparently went to great lengths to touch up their appearance. Moreover, this was just as true in death as it was in life: witness the smooth, serene faces, with regular features and prominent eyes emphasised by dramatic black outlines, typically painted onto cartonnage mummy masks and wooden coffins. “The more I try to understand what the Egyptians themselves understood as ‘beautiful’”, says Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley, “the more confusing it becomes, because everything seems to have a double purpose. When it comes to ancient Egypt, I don’t know if ‘beauty’ is the right word to use.” [Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016. Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph |::|]

“To complicate matters further, there are eye-catching exceptions to the general rule whereby elite ancient Egyptians presented themselves in a stereotypically ‘beautiful’ fashion. Consider the official portraiture of the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senusret III. Although his naked torso is athletic and youthful – idealised, in line with earlier royal portraits – his face is careworn and cracked with furrows. Moreover his ears, to modern viewers, appear comically large – hardly an attribute, you would think, of male beauty. |::|

“Yet, in ancient Egypt, the effect wouldn’t have been funny. “In the Old Kingdom, kings were god-kings,” explains Tyldesley, who is a senior lecturer at the University of Manchester. “But by the Middle Kingdom, kings [such as Senusret] recognised that things could crumble and go wrong, which is why they look a bit worried. The big ears are telling us that this king will listen to the people. It would be wrong to take his portrait literally and say he looked like this.” |::|

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

"Nefertiti's Face: The Creation of an Icon" by Joyce Tyldesley (Harvard University, 2018) Amazon.com;

“Sacred Luxuries: Fragrance, Aromatherapy, and Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt”

by Lise Manniche and Werner Forman (1999) Amazon.com;

”A Catalogue of Egyptian Cosmetic Palettes in the Manchester University Museum Collection” by Julie Patenaude and Garry J. Shaw (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume” by Mary Galway Houston (1920) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry” by Carol Andrews (1991) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“Construction of an Ancient Egyptian Wig in the British Museum” by J.Stevens Cox Amazon.com;

“Historical Wig Styling: Ancient Egypt to the 1830s” by Allison Lowery (2019) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Appearance in Ancient Egypt

Queen Nodjmet

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote:“Bodily modifications, appearance, and grooming were part of the social construction of identity. The ideal elite adult body was clean, well cared for, and scented, with firm musculature for men and slender yet fecund proportions for women. The king’s own body exemplified the ideal male form at all periods. Although most of the mummies thought to be those of kings were not circumcised, male circumcision was practiced (probably around the onset of puberty) to some extent. There is no clear evidence for female circumcision (excision) during the Pharaonic Period, though there may be some indications for the practice, in particular from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. Male circumcision was one of a number of practices related to priestly service, all of which were concerned with purity. Other requirements included washing, cleaning the mouth, shaving body hair, abstaining from sexual activity, and adhering to dietary restrictions. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In art, men were depicted as slightly larger than women of equal status, and women tended to be depicted with proportions different from those of men, with a shorter spinal column in relation to the buttocks and legs. Signs of status and age could be depicted through the body in limited ways, according to accepted conventions: thus older men might have lined faces or thickened bellies, while women’s bodies tended to retain their ideal, slender shape. Both sexes dressed their hair in braids or covered it with wigs and hairpieces. Hairstyles changed with fashion over time, and men sometimes wore trimmed facial hair, such as a thin mustache or a short goatee beard. In some Ramesside tomb paintings, older men and women have white hair . Elite women’s hair was usually long and full, and often worn in tight braids.

“In the vast majority of visual representations, only lower-status figures are shown with paunches, poor posture, creased or snub-nosed faces, or (for men) receding hairlines. Lower-status female figures such as musicians and dancers may bear tattoos and are almost nude, with distinctive hairstyles that set them apart from elite women. Their bodies may likewise adopt more informal postures and gestures, sometimes incorporating rear or frontal views. The same holds true for male and female mourners, whether members of the deceased’s family, household dependants, or paid performers; their gestures, disarrayed hair and clothing, and (for men) unshaven heads and faces mark them out. For both the elite and lower-status figures, expressive gestures were important carriers of meaning, and may be identified in pictorial representation through poses of prayer and begging or supplication.

"Figures with dysmorphic bodies—achondroplastic dwarves, or people with signs of illness or injury—appear in a few more elite instances, representing named individuals. In the Old Kingdom, the dwarf Seneb is one of a number of such individuals represented in art, attesting to the symbolic and social roles attached to dwarfism. The New Kingdom stela of a minor official named Roma represents him leaning on a staff with a withered leg, perhaps evidence of an injury or an illness such as poliomyelitis . The “queen of Punt” relief from Deir el-Bahri depicts a morbidly obese woman, which may reflect the appearance of an actual individual but also fits the trope of assigning stereotypical features to the faces and bodies of non-Egyptians.”

"Figures with dysmorphic bodies—achondroplastic dwarves, or people with signs of illness or injury—appear in a few more elite instances, representing named individuals. In the Old Kingdom, the dwarf Seneb is one of a number of such individuals represented in art, attesting to the symbolic and social roles attached to dwarfism. The New Kingdom stela of a minor official named Roma represents him leaning on a staff with a withered leg, perhaps evidence of an injury or an illness such as poliomyelitis . The “queen of Punt” relief from Deir el-Bahri depicts a morbidly obese woman, which may reflect the appearance of an actual individual but also fits the trope of assigning stereotypical features to the faces and bodies of non-Egyptians.”

Women's Beauty in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian women had make-up tables and a variety of application spoons, vases, flacons, unguents and boxes of eye shadow. They massaged themselves with scented oils, anointed their bodies with animal fat mixed with frankincense, cinnamon and juniper; whitened their faces with cerussite; painted their lips with a brush;

Beauty shops and perfume factories existed in ancient Egypt. The use of make up was common as early as 4000 B.C. The favorite color of eye make-up was green; the favorite shade of lipstick was blue-black. Cheeks were rouged and lips, nails, fingers and feet were stained with henna. No one has yet found an samples of ancient lipstick.

Women also had their fingernails manicured, shaved their eyebrows, applied false eyebrows and red cheek rouge, painted their nails and toenails ruby red, washed their hair, and used kohl (black eye paint). Some adorned their nipples with gold and outlined the veins on their breasts with blue.

Nefertiti’s Bust and Egyptian Beauty

Nefertiti's bust

Nefertiti is perhaps the best known queen of Egypt. She is depicted in more sculpture and artwork than her husband, King Akhenaten. Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Akhenaten's 'great king's wife' was Nefertiti and they had six daughters. There were also other wives, including the enigmatic Kiya who may have been the mother of Tutankhamun." Nefertiti is thought to have been a princess from Mitanni (a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia). She initially encouraged and supported her husband in with his revolutionary religious views but later appeared to have a falling out with him perhaps over the same views. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

The famous bust of Nefertiti is shown above. Joyce Tyldesley, professor at the University of Manchester and author of a biography about Cleopatra, told the BBC: Nefertiti’s bust is not typical of ancient Egyptian art: “It’s an unusual statue in that it’s got all the plaster on and it’s colourful – a lot of the artwork we have is more stereotyped and less personal-looking than that.”[Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016. Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph |::|]

Alastair Sooke wrote for the BBC: “The moment when the bust was unveiled in Berlin – in 1923 – was crucial to its reception. ‘Egyptomania’ was in the air, following the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun the previous year, and Nefertiti’s angular, geometric appearance chimed with fashionable taste. “She’s very modern-looking, very Art Deco,” says Tyldesley. “So everybody seemed to like her. It’s hard to find anybody who didn’t think that Nefertiti was beautiful.” |::|

“During the ’20s, the bust of Nefertiti also benefited from the power of the mass media to turn her into a star. “A hundred years earlier, without newspapers or the cinema, that wouldn’t have happened,” says Tyldesley. “She would have gone into a museum and nobody would have made the fuss they did. I wonder whether the fact that Nefertiti was put on display in Berlin as a major find actually influenced what we saw. After all, beauty, as we know, is in the eye of the beholder.” “|::|

Cleopatra and Beauty

Since ancient times, Cleopatra has been regarded as a paragon of beauty. Plutarch wrote: "Her beauty was not incomparable” but “the attraction of her conversation...was something bewitching...The persuasiveness of her discourse and her character...had something stimulating about it. It was a pleasure merely to hear her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to the next...Plato admits four sorts of flattery but she has a thousand." Another historian described her countenance as "alive rather than beautiful."

Cleopatra

The 2nd century Greek historian said that Cleopatra seduced men because she was "brilliant to look upon...with the power to subjugate everyone." She would later become "a woman of insatiable sexuality and insatiable avarice" (Dio), "the whore of the eastern kings" (Boccaccio). She was a carnal sinner for Dante, for Dryden a poster child for unlawful love. A first-century A.D. Roman would falsely assert that "ancient writers repeatedly speak of Cleopatra's insatiable libido." Florence Nightingale referred to her as "that disgusting Cleopatra." Offering Claudette Colbert the title role in the 1934 movie, Cecile B. DeMille is said to have asked, "How would you like to be the wickedest woman in history?" [Source: Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010, Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff]

Images close to her time contradict the notion that she a great beauty. The pictures of Cleopatra depicted on Roman coins shows a woman with a large hooked Semitic nose, sharp chin, boney face, narrow forehead and large eyes. Stacy Schiff wrote in her book Cleopatra: A Biography, “If the name is indelible, the image is blurry. She may be one of the most recognizable figures in history, but we have little idea what Cleopatra actually looked like. Only her coin portraits — issued in her lifetime, and which she likely approved — can be accepted as authentic." Cleopatra herself claimed pickles made her beautiful

Joyce Tyldesley, professor at the University of Manchester and author of a biography about Cleopatra, told the BBC: “Cleopatra has given us the idea that ancient Egyptian women were all beautiful, but we don’t actually know what she looked like.” In her coinage, “Cleopatra had a big nose, a protruding chin, and wrinkles – not what most people would call beautiful. You could argue that she appeared on her coins like that on purpose, because she wanted to look stern, and not particularly feminine. But even Plutarch, who never met her either, said that her beauty was in her vivacity and her voice, and not in her appearance. Yet we have decided that she was beautiful and that she has to look like Elizabeth Taylor. I think that the idea of Cleopatra, rather than Cleopatra herself, has influenced us.” [Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016]

Men's Beauty in Ancient Egypt

Many Egyptian men, including pharaohs and ordinary fishermen, wore make up. Men also painted their nails and wore earrings and anklets. A relief from 2400 B.C. in the tomb of the nobleman Ptahhotep, showed him getting a pedicure.

There is evidence that men shaved as far back as 20,000 years ago. The ancient Egyptians equated clean-shaven faces with nobility. Bronze razors have been found in the graves of high-status men.

In King Tutankhamun's tomb, dated at 1350 B.C., archaeologists found jars of skin cream, lip color, cheek rouge and still usable fragrances. Men used cosmetics such as sunscreen and skin lubricant.

Hairstyles in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian men were usually clean shaven and sported both long and short hair styles. Men wore their hair long; boys had their heads shaved except for a lock of hair above their ear. A male body from a working class cemetery in Hierakonpolis dated around 3500 B.C. had a well trimmed beard.

Ancient Egyptians sported curls, braids, waves, twists, wigs and extentions, They dyed their hair and cut it short like U.S. Marines. Kozue Takahashi of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “Egyptians threaded gold tubes on each tress, or strung inlaid gold rosettes between vertical ribs of small beads to form full head covers. The also used combs, tweezers, shavers and hair curlers. Combs were either single or double sided combs and made from wood or bone. Some of them were very finely made with a long grip. Combs were found from early tomb goods, even from predynastic times. Egyptians shaved with a stone blade at first, later with a copper, and during the Middle Kingdom with a bronze razor.” [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Women sometimes wore long things in their hair. A female body from a working class grave dated around 3500 B.C. had evidence of hair coloring (henna was used to color grey hair) and hair weaving (locks of human hair were tied to natural objects to produce an elaborate beehive hairdo). A grave in the worker’s cemetery at Hierakonpolis revealed a woman in her late 40s or early 50s with a Mohawk. Egyptians darkened grey hair with the blood of black animals and added false braids to their own hair.

See Separate Article: HAIRSTYLES, WIGS, FACIAL HAIR AND HAIR CARE IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

Beauty Aids in Ancient Egypt

Cheryl Dawley of Minnesota State University, Mankato, wrote: “Egyptians were vain in their appearance. Cosmetics, perfumes and other rituals were an important part of their dress. Red ochre mixed with fat or gum resin was thought to be used a lipstick or face paint. Mixtures of chalk and oil were possibly used as cleansing creams. Henna was used as hair dye and is still in use today. [Source: Cheryl Dawley, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Toilet box and various vessels “Oils and creams were very important against the hot sun and dry, sandy winds. The oils kept skin soft and supple and prevented ailments caused by dry cracked skin. Workers considered these oils and ointments to be a vital part of their regular wages such that when they were withheld, grievances were filed during the reign of Ramesses III. “ /+/

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “The adornment of the body through dress, cosmetics, jewellery, and ornaments was an extension of the bodily self...“The importance of grooming and adorning the body is reflected in the number of cosmetic preparations and utensils buried with the dead, along with jewelry and artifacts worn on the body. This pattern of grave goods is observed already in prehistoric times, when combs, pins, tags, beads, and cosmetic vessels dominate burial assemblages.” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

In 2016, an exhibition called Beyond Beauty — - focusing mostly on Egyptian beauty products— was organised by the charitable foundation Bulldog Trust at Two Temple Place in central London. On the 350 featured exhibits the,Alastair Sooke wrote for the BBC, “There are dinky combs and handheld mirrors made of copper alloy or, more rarely, silver. There are siltstone palettes, carved to resemble animals, which were used for grinding minerals such as green malachite and kohl for eye makeup. [Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016. Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph |::|]

“There are also pale calcite jars and vessels of assorted sizes, in which makeup, as well as unguents and perfumes, could be stored. Then there is a scrap of human hair that suggests the ancient Egyptians commonly wore hair extensions and wigs. And, of course, there are lots of striking examples of Egyptian jewellery, including a string of beads, decorated with carnelian pendants in the shape of poppy heads, found in the grave of a small child wrapped in matting.” |::|

Ancient Egyptian Cosmetics and Make Up

Duck-shaped kohl spoon In ancient Egypt cosmetics were widely used by both men and women. Black eyeliner was widely used. Ocher was applied for rouge. Oils and creams, often scented, kept skin moist in the dry climate. Sometimes cosmetics were even given as part of one’s wages.

Cosmetics were believed to be imbued with magical powers. Wearing green eye paint, or “ awadju”, was thought to summon the protection of Hathor, the goddess of beauty.

Even in death cosmetics were regarded as a key to maintaining a youthful appearance. Among the objects buried with he dead to meet their needs in the afterlife were cosmetics, cosmetic spoons, palettes for on which kohl and ocher could be ground into cosmetics using polished stones, tubes to store eyeliner, jars of moisturizer, ivory hair combs, fragrant cedar and juniper.

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: Scented and moisturizing preparations were widely used for skin and hair, along with cosmetics, in particular green and black eye make-up made from malachite and galena, respectively. Cosmetic lines extending the eyebrows and the outer eye corners can indicate elevated or other-worldly status in art, being applied, for instance, to the king, the gods, and the transfigured dead. Skin color also had symbolic aspects in art: reddish brown paint was typically used to represent men, and light red or yellow for women, although there are a number of exceptions to these general observations. Yellow and white skin color symbolized the shining, bright skin of the gods and the transfigured dead, while deities like Osiris could be shown with black or green skin.” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: COSMETICS AND MAKE UP IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Tattoos in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian women were also fond of tattoos. Singers, dancers and prostitutes wore them and some wore cones of unguent at parties that melted and covered their bodies with scent.

Cheryl Dawley of Minnesota State University, Mankato, wrote: “Tattooing was known and practiced. Mummies of dancers and concubines, from the Middle Kingdom, have geometric designs tattooed on their chests, shoulders and arms. In the New Kingdom, tattoos of the god Bes could be found on the thighs of dancers, musicians and servant girls.” [Source: Cheryl Dawley, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Alastair Sooke wrote for the BBC: “A fired clay female figure, depicting an erotic dancer, excavated at Abydos in Upper Egypt and now in the exhibition at Two Temple Place, is embellished with indentations that were meant to represent tattoos. Of course, in ancient Egypt, tattoos probably had a decorative purpose. But they may have had a protective function too. There is evidence that, during the New Kingdom, dancing girls and prostitutes used to tattoo their thighs with images of the dwarf deity Bes, who warded off evil, as a precaution against venereal disease.” [Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016. Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph |::|]

See Separate Article: TATTOOS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Perfume in Ancient Egypt

baboon-shaped perfume vessel

"Perfume" — a Latin word meaning "through smoke" — comes to us from the Mesopotamians and Egyptians, who used the burnt resin from desert shrubs such as myrrh, cassia, spikenard and frankincense for their aromatic fragrance. Pharaohs burned incense as an offering to the gods and were embalmed with cumin, marjoram and cinnamon. The ancient Egyptians believed that bad odors caused disease and good ones chased them away. Perfumes and fragrances were rubbed on the body for health reasons and to ward off curses. At parties men wore garlands of flower and perfume and spread powdered perfume on their beds so their bodies would absorb the scent during the night. Flower petals were scattered on the floor and perfumed water poured from orifices in statues.

The Egyptians developed ornate glass vessels to hold perfume and developed the process of effleurage (squeezing aromatics into fatty oils). Cedarwood was used to give house and mummies a fresh smell; incenses was used to protect papyrus from insects.

Lise Manniche of the University of Copenhagen wrote: “In ancient Egypt, scent was released in the form of incense, or it was prepared on a base of oils or fat. Although distillation appears to have been known in parts of the ancient world c. 2000 B.C., there is as yet no proof of its having been applied in Pharaonic Egypt... Perfume in Egypt was fat-based, and the ingredients most often mentioned in texts are frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon, cassia, and cardamom. Scent had an important role in temple and funerary ritual. Furthermore, perfume was a luxury item and a commodity traded in the Mediterranean. [Source: Lise Manniche, University of Copenhagen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: PERFUMES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo and Livescience (the mummy tattoo)

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024