Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

EVERYDAY LIFE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

beer making Herodotus devoted nearly all of Book 2 of “History to describing the achievements and the curiosities of the Egyptians. On the Egyptian customs Herodotus reported "In any home where a cat dies" the residents "shave off their eyebrows" and “sons never take care of their parents if they don’t want to, but daughters must whether they like it or not." He also noted “Women urinate standing up, men sitting down.”

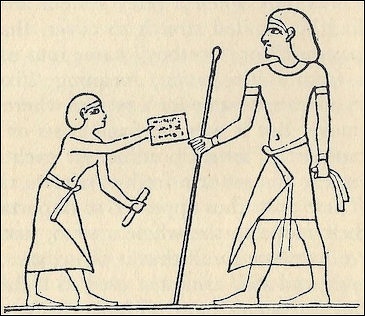

The Egyptians built canals and irrigation systems. They didn’t make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. In 2300 B.C. the ancient Egyptians built channels through the first cataract of the Nile, where the Aswan Dan stands today. This helped open the way for trade between the Pharaohs and Africa. Messages were sent along the Nile. Seals were the equivalent of signatures. They were applied on wet mud with a paint-roller like cylinder.

In his book “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” Toby Wilkinson paints a sobering portrait of what daily life was like for ordinary Egyptians. In a review of the book Michiko Kakutani wrote in New York Times, “Foot soldiers (who actually fought barefoot) were subject to frequent beatings and had to subsist on meager rations, which were supposed to be supplemented “by foraging and stealing.” And peasants, who did not have access to the doctors and dentists available to the wealthy, suffered from a range of debilitating diseases like tuberculosis and parasitical infections. To make matters worse, high taxes, the uncertain nature of agriculture in the Nile Valley (either too much water or too little) and the constant threat of famine combined to make daily life feel perennially precarious.” [Source: Michiko Kakutani, New York Times March 28, 2011]

Small wonder, then, Mr. Wilkinson says, that fervent belief in an afterlife — once largely the preserve of the ruling class, who regarded mummification and pyramids as vehicles for overcoming death — spread gradually to the population at large. The nature of an afterlife changed too. Whereas the wealthy, Mr. Wilkinson writes, “had been content to look forward to an afterlife that was essentially a continuation of earthly existence,” Egyptians increasingly came to hope for “something better in the next world,” to believe in the idea of “transfiguration and transformation” — an idea that “would echo through later civilizations and ultimately shape the Judeo-Christian tradition.”

Texts like “The Story of Sinuhe,” “The Eloquent Peasant,” “The Report of Wenamun , “The Tale of Woe,” and The Teaching of Ankhsheshonq” are interesting stories in their own right but also offer invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian society and the daily life or ordinary Egyptians.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

See Food, Labor

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Jon Manchip White (2012) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Egypt: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Donald P. Ryan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Daily Activities in Ancient Egypt

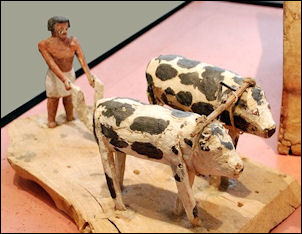

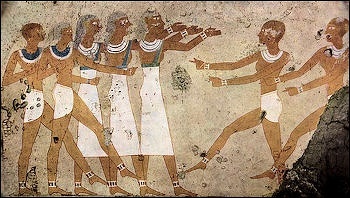

Modern Egyptians have many of the same daily chores and habits as their ancient ancestors. Bricks are still made by mixing river silt with straw and then shaping the muck into blocks and baking them in the sun; flax is still harvested by hand by pulling up the plants up by their roots; alabaster bowls are still shaped and polished with a drill weighted by stones and twisted by hand; men still tell folk tales while recreating a battle with a stick dance; women still supplicant themselves to the dead; and women winnow grain by tossing it into the wind after the grain has been still threshed by oxen going round and round with a sled over a pile of stalks. [Source Live Science]

Modern Egyptians have many of the same daily chores and habits as their ancient ancestors. Bricks are still made by mixing river silt with straw and then shaping the muck into blocks and baking them in the sun; flax is still harvested by hand by pulling up the plants up by their roots; alabaster bowls are still shaped and polished with a drill weighted by stones and twisted by hand; men still tell folk tales while recreating a battle with a stick dance; women still supplicant themselves to the dead; and women winnow grain by tossing it into the wind after the grain has been still threshed by oxen going round and round with a sled over a pile of stalks. [Source Live Science]

Juan Carlos Moreno García wrote: Microhistory is a rather ambiguous term, usually referring to the lives, activities, and cultural values of common people, rarely evoked in official sources. In the case of ancient Egypt, both the urban and village spheres provide some clues about the existence, social relations, spiritual expectations, and life conditions of farmers, craftspersons, and “marginal” populations (such as herders), and also about “invisible” elites that played so important a role in the stability of the kingdom. In some instances, exceptional archives (the Ramesside tomb-robbery papyri, Papyrus Turin 1887, recording the “Elephantine scandal,” and the thousands of ostraca recovered at Deir el-Medina) cast light on the realities of social life, in which crimes and reprehensible practices appear quite common. In other cases, structural archaeological evidence reveals the harsh conditions under which many Egyptians lived and died. Finally, small private archives, often associated with temple activities, reveal how some individuals managed to thrive and to follow personal strategies that enabled them to accumulate moderate wealth. Microhistory clearly has a role to play in Egyptology in balancing the information provided by official texts, with their biased perspectives of the social order and cultural values prevailing in the Nile Valley. [Source Juan Carlos Moreno García, University of Paris IV-Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018; escholarship.org ]

Documents cast light on the community’s conflicts and social practices, from gifts among ladies to the promotion of royal cults by local scribes, from theft to pious donations, from literacy and the possession of private libraries to strikes and small economic operations involving donkeys, credit, or transfers of slave-days. Mention should additionally be made of the Middle Kingdom Egyptian fortresses in Nubia and of the Old Kingdom settlement at Balat, in the Dakhla Oasis. We observe that administrative practices and formal hierarchies were quite visible in these specialized communities when the central government was strong, and that, moreover, when the central government collapsed, these communities continued to thrive, revealing that, beyond their official function, their inhabitants enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, irrespective of any central instruction or support.

More elusive communities comprised Egyptians who settled and lived in the Levant following the imperial expansion of the New Kingdom. A number of these individuals may have constituted an Egyptian “trading diaspora” involved in commerce and other activities. In other cases they were soldiers, administrators, or simply settlers whose culinary tastes (such as the consumption of Nile perch) and toilette customs make them visible in the archaeological record and distinguishable from the local, Levantine populations. The Story of Sinuhe and The Tale of Woe, whether fictional in nature, reveal nevertheless the anxieties and expectations of exiles living outside the Nile Valley and the importance they attached to the precise adherence to Egyptian customs regarding food and the care of the body. The adaptability exhibited by the inhabitants of the Nubian fortresses, surely related to the non-institutional nature of their activities (mainly trade), explains why the fortress dwellers thrived both when the Egyptian monarchy was strong and centralized and when it collapsed. This could also explain why the fortresses were often surrounded by non-walled settlements in which a mixed population of Nubians and Egyptians lived and traded: Egyptian “colonists” apparently hadlittle to fear from their Nubian neighbors.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Microhistory by Juan Carlos Moreno García escholarship.org

Individuality and Ordinary Life in Ancient Egyptian Art

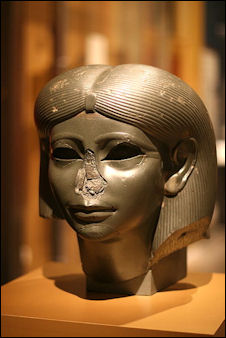

Souren Melikian wrote in New York Times the remarkable show “Haremhab, the General Who Became King” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the summer of 2011 — which zooms in on the time of Haremhab, the military chief who wielded immense power before ruling as a pharaoh from around 1316 to 1302 B.C.”dispels the long-held myth that ancient Egypt was a culture solely concerned with timeless icons of gods and kings in postures dictated by canon even if that is not the purpose of the show. Viewers discover that images of humans lost in their private thoughts and beset by anxiety already appeared in Egypt by the mid-third millennium B.C. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, May 20, 2011]

Souren Melikian wrote in New York Times the remarkable show “Haremhab, the General Who Became King” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the summer of 2011 — which zooms in on the time of Haremhab, the military chief who wielded immense power before ruling as a pharaoh from around 1316 to 1302 B.C.”dispels the long-held myth that ancient Egypt was a culture solely concerned with timeless icons of gods and kings in postures dictated by canon even if that is not the purpose of the show. Viewers discover that images of humans lost in their private thoughts and beset by anxiety already appeared in Egypt by the mid-third millennium B.C. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, May 20, 2011]

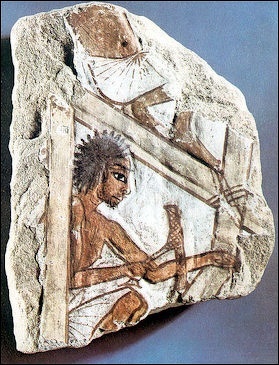

Among a few works serving as an introduction to Haremhab’s lifetime, the small figure of a scribe, probably from Saqqara in the area of ancient Memphis, is seen seated cross-legged, holding a papyrus scroll unrolled on his lap. The hieroglyphic inscription engraved on the scroll states his name, Nikare, and his title, scribe, one of the highest offices in the ancient Egyptian administration.

At first glance, the granite statue follows the canonical representation of the official who mastered the difficult art of hieroglyphs. On closer inspection, a personalized portrait can be made out. The man, no longer in his prime, is hunched, as if bending under the weight of his concerns. Light furrows come down from his nose. No smile lights up his face. Subtle as it may be, the suggestion of weariness is unmistakable in Nikare’s three-dimensional likeness.

About four centuries later, an artist carving scenes on the limestone walls of a funerary chamber in ancient Thebes, depicted another scribe with his reed brush stuck behind his ear. A tiny fragment, 10.9 by 9.2 centimeters, or 4 5/16 by 3 5/8 inches, is preserved, showing part of the head in profile. Excavated by a Metropolitan Museum team around 1911-12, it is believed to date from 2000 B.C., give or take 20 years. The tomb was that of a pharaoh’s vizir called Dagi who may have employed the scribe. The man stares glumly. His raised eyebrow suggests incredulity. If the sculptor meant to convey the shock of a man who has suddenly been made aware of his mortality, he could not have done it better.

At rare intervals, the private life of ancient Egyptians and the feelings that they experienced moved artists to stray away from the beaten path. An intriguing sculptural group of two men at different stages of life and a young boy at their side was probably carved during the reign of Akhenaten, the pharaoh who revolutionized Egyptian thinking by proclaiming that there is only one God, some time between 1349 and 1332 B.C. On the low reliefs that depict him, Akhenaten is seen with a smile of mystical illumination. But when looking at the father and son, the anonymous artist portrayed ordinary humans.The father, who stands in the middle, embraces his son in a protective gesture, with his hand coming down over the boy’s shoulder. A sense of harmonious intimacy emanates from the happy family scene.

But, even when they set out to portray the great and the good, the ancient Egyptian artists sometimes took note of the sitters’ frame of mind. Idealized as it is, the famous Metropolitan Museum’s statue of Haremhab as a scribe, carved when he was still a general, betrays a certain weariness: hardly surprising in a man who had a full hand — as the commander in chief of the Egyptian army, he organized campaigns against the Hittites in faraway Anatolia to the northeast and Nubia on the southern front.

Lesser characters were prone to be depicted in a more individualized fashion. The small granite figure of an unidentified scribe carved between 1295 and 1070 B.C. shows a man looking alert and concerned. Eyes wide open, with his eyebrows slightly raised, the scribe presses his lips as if he had just been given an admonition about his performance.

Hieroglyphics That Offer a Glimpse Into Ancient Egyptian Life

model of a farm scene Toby Wilkinson, an Egyptologist at the University of Cambridge, produced a book, called “Writings From Ancient Egypt“, which is comprised of texts from poets, scribes, priests, storytellers and everyday citizens spanning some 2,000 years of Egyptian civilization that offer an interesting glimpse into ancient Egyptian life and society. “It’s always struck me that people think of Egypt as a civilization that produced great art and great architecture, the pyramids, the temples and so forth, but we’re missing a huge dimension of that society if we fail to engage with the writing that the ancient Egyptians left behind,” Wilkinson told Discover magazine. [Source: Nathaniel Scharping, Discover, September 22, 2016 =]

Nathaniel Scharping wrote in Discover: “The texts gathered in the book, which comprise merely a fraction of what they put to papyrus, include samples authored by characters from all levels of society, providing a counterpoint to the god-kings in museum exhibits that often stand in for the entirety of Egyptian society today. =

“We have been able to read the Egyptians’ writing ever since the translation of the Rosetta Stone in 1803, but most of it has remained the purview of scholars. Wilkinson says that most texts dealing with their writing are kept in university libraries, written dryly and meant for academics. He aims to introduce the writings to a broader audience and hopefully illustrate an oft-overlooked fact about Egyptians: that they were people too. “It turns them into real people, rather than just the inhabitants of a long [ago], far-off and sort of remote civilization, they really shine through these writings as people like you and me with the same sort of hopes and fears and interests,” says Wilkinson. =

“There is, for example, the tale of a sailor trapped on a desert island with a giant snake possessing eyes of lapis lazuli that bears similarities to more modern fairy tales and mythical journeys. On a more prosaic level, the collection includes a letter from a minor landowner to his steward, conveying instructions about a misbehaving servant: “Now have that housemaid Senen thrown out of my house – see to it – on whatever day Sahathor reaches you. Look, if she spends a single day (more) in my house, act! You are the one who lets her do bad things to my wife. Look, how have I made it distressful for you? What did she do against you (to make) you hate her? And greetings to my mother Ipi a thousand times, a million times. And greetings to Hetepet and the whole household and Nefret. Now what is this, bad things being done to my wife? Enough of it! Are you given equal rights with me? It would be good if you stopped.”“ =

Life of the Pyramid Builders

Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester: “To the south of the pyramid town lay an industrial district, a gigantic, cohesive complex divided into blocks or galleries separated by paved streets equipped with drains, and including some workers' housing.” There “Lehner has already discovered a copper-processing plant, two bakeries with enough moulds to make hundreds of bell-shaped loaves, and a fish-processing unit complete with the fragile, dusty remains of thousands of fish. This is food production on a truly massive scale, although as yet Lehner has discovered neither storage facilities nor the warehouses. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|] Lehner told National Geographic, "I'm less interested in how the Egyptians built the pyramids than in how the pyramids built Egypt...Imagine yourself as a 15-year-old kid in some rural village of about 200 people in the 27th century B.C. One day the pharaoh's men come. They say, 'You and you, and you.' You get on a boat and sail down the Nile." "Eventually you came around a bend and you see this huge geometric structure, like nothing you've ever known. there are hundreds of people working on it. They put you to work. And someone keeps track of you: your name, your hours, your rations. All this was a profoundly socializing experience . You might go back to your village, but you would never be the same."[Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

Lehner told PBS: “You're rotated into this experience, and you serve in your respective crew, gang, phyles, and divisions, and then you're rotated out, and you go back because you have your own large household to whom you are assigned on a kind of an estate-organized society. You have your own village, maybe you even have your own land that you're responsible for. So you're rotated back, but you're not the same. You have seen the central principle of the first nation-state in our planet's history—the Pyramids, the centralization, this organization. They must have been powerful socializing forces. Anyway, we think that that was the experience of the raw recruits.” [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

“But there must have been a cadre of very seasoned laborers who really knew how to cut stone so fine that you could join them without getting a razor blade in between. Perhaps they were the stone-cutters and-setters, and the experienced quarry men at the quarry wall. And the people who rotated in and out were those doing all the different raw labor, not only the schlepping of the stone but preparing gypsum.” [Ibid]

A excavation near the Sphinx and underneath the Cairo suburb of Nazlat as Samman has revealed the first settlement occupied by the pyramid builders. As of 1992 the dig had reveled 159 tombs with the remains of an overseer and major craftsmen; a storage building, perhaps a granary; a massive bakery with a hearth and containers resembling egg cartons, which held the thousands of loaves of bread baked daily; and a huge wall with a 21 foot high gateway through which workmen passed to and from the Pyramids. [National Geographic Geographica, May 1992]

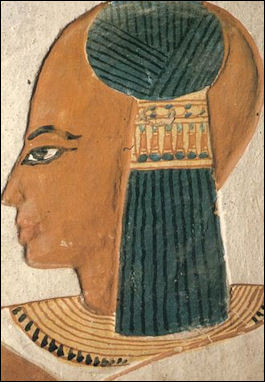

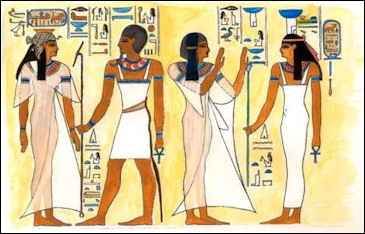

Ancient Egyptian Clothes

Egyptians wore kilt-like, tunic-like and robe-like garments like those pictured in tomb painting. In many cases the garments worn by pharaohs and nobles wasn’t all that different from those worn by ordinary Egyptians. Egyptian clothes had no buttons or zippers. They were either tied or tucked.

Egyptians wore kilt-like, tunic-like and robe-like garments like those pictured in tomb painting. In many cases the garments worn by pharaohs and nobles wasn’t all that different from those worn by ordinary Egyptians. Egyptian clothes had no buttons or zippers. They were either tied or tucked.

People generally didn't wear underwear. Men and women sometimes went topless. Ordinary men often wore loin clothes and went bare chested. Even when women wore tops breasts were visible in the thin fabric. Egyptian noblemen used parasols, carried by slaves for protection from the sun.

Egyptians didn't wear hats. They sometimes wore hair bands to keep their hair out of their face of wigs. The Egyptians didn't need gloves for warmth, but women wore soft linen gloves, sometimes embroideried with colored threads, as a decorative accessory.

Commoner men (pyramid builders) wore loin clothes and women dressed in long sheaths attached above the breasts with a shoulder strap. Women also wore ankle-length skirts. The pharaoh’s kilt was called a “shendyt”.

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “ The garments depicted in art do not correspond well to those discovered through archaeology, underscoring the idealization of pictorial representations. Clothing found in archaeological contexts is cut-to-shape or left in rectangular form from the loom, with long, loose tunics to be pulled on and off over the head, and many types of wraps, shawls, and mantles, which could be folded and knotted to yield different garment types. In art, tight-fitting dresses or diaphanous robes (for women), and kilts that mold to the buttocks but are voluminous in the front, hiding the genitals (for men), are more concerned with revealing and concealing parts of the body than accurately depicting the clothes that Egyptians wore. Similarly, the nudity of children and lower-status females is symbolic.” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Articles: CLOTHES AND JEWELRY IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Hygiene in Ancient Egypt

In the dry climates of Mesopotamia and Egypt, cleanliness, washing and bathing for some was not given a high priority. But those close to Nile had better access to water than those who were not near the river.

The Egyptians values cleanliness. The Nile and various oasis supplied them water and some scholars credit them with inventing the custom of bathing. Bas-reliefs and tomb paintings showed attendants pouring water over bathers. Bathing was an important aspect of some religious ceremonies. Priests were required to bath four times a day. By 1500 B.C. some homes of Egyptian aristocrats were outfit with copper pipes that carried hot and cold water.

Upper class Egyptians bathed with soda instead of soap and used waters scented with oils and alcohols of honeysuckle, hyacinth, iris, and jasmine. The oldest known image of washing cloth was found in the tomb of Beni Hasan in ancient Egypt. It dates to around 2000 B.C. Egyptians liked fresh linen and used body ointments and skin conditioners. The Ebers Papyrus describes the treatment of skin diseases with soaplike materials made from animal fats, vegetable oils and alkaline salts.

See Separate Articles: HYGIENE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: SANITATION, TOILETS, DEODORANT, TOOTHPASTE africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Light and Energy

.jpg)

Bundles of wood In ancient times, olive oil was used in everything from oil lamps to religious anointments and to cook and prepare condiments and medicines. It was in great demand and traveled well and people like the Philistines grew rich trading it.

About 50,000 years ago pre-historic man used lamps made of a fibrous wick fueled by animal fat. Beginning around 1300 B.C., Egyptians used earthen oil lamps with papyrus wicks to light temples and homes. The lamps were fueled by edible olive oil or vegetable oil, and animal fats, which could be consumed in times of food shortages.

The main source of light in ancient Egypt were dim illuminations that came from wicks burning in a bowl of oil salted to reduce smoke. Wicks were cut to last eight hours.

Some of the earliest lamps were made from sea shells. These were observed in Mesopotamia. Lamps made from man-made materials such as earthenware and alabaster appeared between 3500 and 2500 B.C. in Sumer, Egypt and the Indus Valley. Metal lamps were rare. As technology advanced a groove for the wick was added, the bottom of the lamp was titled to concentrate the oil and the place where the flame burned was moved away from the handle. Mostly animal fats and vegetable and fish oils were burned. In Sumer, seepage from petroleum deposits was used. The wicks were made from twisted natural fibers.

The first references to oil were made on cuneiform tablets in Babylonia in 2000 B.C. It was referred to as naptu , which means "that which flares up." Mesopotamians were fascinated by naphtha especially since fire created with it could not be put out with water. At that time oil came primarily from seepages. Evidence from cuneiform tablets indicates that petroleum products were used for torches, lamps, mortars, pigments, textile finishes, magic fire tricks, medicines, and incendiary weapons. One tablet read: "If a certain place in the land naptu oozes out, that country will walk in widowhood. If the water of a river bears...oil, want will seize on the peoples." Another states: "May donkey urine be your drink, naptu your ointment." Naptu was used as a skin ointment.

Oils in Ancient Egypt

We can scarcely realize the importance of oil in ancient Egypt. Oil was a necessary of daily life, and the hungry unpaid workmen complain in the same breath that no food is given them to eat, and that no oil is given to them. These workmen had probably to be contented with native fat, but the soldiers demanded imported oil — oil from the harbor? [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

People of rank always obtained their oils and perfumes from foreign countries, in preference from the south coasts of the Red Sea, which supplied the precious ointment so often mentioned and so often represented, which was used under the New Kingdom for oiling the head. The oil was not used as we should naturally imagine. A ball about the size of a fist was placed in the bowl of oil; the consistency of the ball is unknown, but at any rate it absorbed the oil. The chief anointer, who was always to be found in a rich household, then placed the ball on the head of his master, where it remained during the whole time of the feast, so that the oil trickled down gradually into the hair.

Oil in Egypt was also symbolic; it was an emblem of joy. On festival days, when the king's procession passed, all the people poured “sweet oil on their heads, on their new coiffures. " “At all the feasts cakes of ointment were quite as necessary as wreaths, and if the king wished specially to honor one of his courtiers he ordered his servants to anoint him with oil, and to put beautiful apparel and ornaments upon him. " It was considered a suitable amusement at a feast for persons to perform their toilettes together, and while or put on new necklets and eating they would anoint themselves, exchange flowers.

Urban Life in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “A passage from “The Teaching for Merikara” warns against demagogues who agitate the spirits of citizens. While the setting of the narrative corresponds to the First Intermediate Period, the actual date of the text’s composition is still debated. However, many First Intermediate Period inscriptions reveal that cities and their “public opinion” had become important enough to have their role recognized and respected by local authorities. [Source Juan Carlos Moreno García, University of Paris IV-Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018; escholarship.org ]

Later, during the early centuries of the first millennium B. C. , Demotic sapiential texts evoke a world of villages and towns dominated by “big men. ” In both cases, both cities and small settlements provided personal and social identities hardly evoked at all in official texts — identities in which men were advised against marrying women from other villages and towns, and in which service in the temples and service to the king provided prestigious, or at least complementary, alternatives of self-presentation. It was not by chance that the concept of city-god had been a source of collective identity since the third millennium B. C. .

Despite the scarce evidence preserved, literary texts evoke the role of taverns as foci of sociability, frequented not only by ordinary people (and diverting students from their studies) but by an underworld of prostitutes. Thus, the idle scribe described in Papyrus Anastasi IV wanders in the streets, drunk and in the company of harlots. It is also possible that independent artists were part of this world, as the greedy and out-of-tune harpist satirized in a Demotic composition. Unfortunately, little is known about petty crime, gangs, rogues, and the dubious characters that might have proliferated in big cities, especially in harbors. Traders and merchants were certainly part of the urban population, perhaps a significant one, judging from Mesopotamian parallels and from the neighborhoods and harbor facilities in which they lived and worked.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Microhistory by Juan Carlos Moreno García escholarship.org

Amarna as a Thriving Egyptian City

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Not only was Akhetaten the center for worship of the Aten and the dwelling place of the king, it was the home of a large population—an estimated 30,000 people, nowhere signaled in the provisions of the boundary stelae. When the city was abandoned after about two decades, the streets and structures with their archaeological evidence were preserved in the state in which they were left after removal of much of the stonework and destruction of statuary. Because the city was not impacted by use over long periods of evolution, the site constitutes a remarkable laboratory for observation of an ancient society, albeit a very particular one created from the ground up at a specific moment. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“A large population of officials and their dependents migrated to the city with the king. Villas of officials were scattered throughout the city; each villa or every few villas had a well, and that nucleus was then surrounded by smaller houses arranged according to the lights of their inhabitants. Amarna's excavator Barry Kemp has aptly described clusters thus formed as village-like, and he has referred to the city they formed as an "urban village." The grouping of smaller houses around an official's house points to the attachment of dependents to a given official, but also to the fact that the members of the complex were all aware of each other as interdependent in a way common to small villages.

“The city offers a good deal of information about the spiritual concerns of its people, although the disparate evidence leaves many gaps and questions. As for involvement in the official Aten religion and the temples, officials presumably commissioned some of the temple statuary of the royal family or small-scale temple equipment at workshops distributed throughout one whole zone of the city. Some of the society at least also seems to have had particular access to certain parts of the temple: the Stela Emplacement area toward the back is one example already noted. Certain figured ostraka or carved single ears—known elsewhere as dedications asking for a god's attention to prayers—may likewise be offerings deposited at some locale in the temples . Moreover, the huge bakeries attached to the Great Aten Temple, along with the many hundreds of offering tables in the temple, point to wide distributions of food, and these could be tied to broad accommodation within areas of the temple enclosure, possibly in connection with the festivals of the Aten promised on the boundary stelae. In their homes, officials might exhibit devotion to the royal family as the children of the Aten, sometimes constructing small chapels in gardens alongside their houses for their own or perhaps neighborhood use.

See Separate Articles: AMARNA: LAYOUT, BUILDINGS, AREAS, HOUSES, INFRASTRUCTURE africame.factsanddetails.com ; AKHENATEN AND AMARNA africame.factsanddetails.com

Satire of the Trades

A text called “The Satire of the Trades” from “ Instruction of Dua-Khety”from the Middle Kingdom (2050- 1710 B.C.) offers a scribe’s unflattering view of various jobs. It goes: “I do not see a stoneworker on an important errand or a goldsmith in a place to which he has been sent, but I have seen a coppersmith at his work at the door of his furnace. His fingers were like the claws of the crocodile, and he stank more than fish excrement. [Adolf Erman, “The literature of the ancient Egyptians; poems, narratives, and manuals of instruction, from the third and second millennia B. C.,” 1927, London, Methuen & co. ltd., pp. 67f. reshafim.org]

carpenters

“Every carpenter who bears the adze is wearier than a fieldhand. His field is his wood, his hoe is the axe. There is no end to his work, and he must labor excessively in his activity. At nighttime he still must light his lamp. The jeweler pierces stone in stringing beads in all kinds of hard stone. When he has completed the inlaying of the eye-amulets, his strength vanishes and he is tired out. He sits until the arrival of the sun, his knees and his back bent at (the place called) Aku-Re. The barber shaves until the end of the evening. But he must be up early, crying out, his bowl upon his arm. He takes himself from street to street to seek out someone to shave. He wears out his arms to fill his belly, like bees who eat (only) according to their work.

“The reed-cutter goes downstream to the Delta to fetch himself arrows. He must work excessively in his activity. When the gnats sting him and the sand fleas bite him as well, then he is judged. The potter is covered with earth, although his lifetime is still among the living. He burrows in the field more than swine to bake his cooking vessels. His clothes being stiff with mud, his head cloth consists only of rags, so that the air which comes forth from his burning furnace enters his nose. He operates a pestle with his feet with which he himself is pounded, penetrating the courtyard of every house and driving earth into every open place.

“I shall also describe to you the bricklayer. His kidneys are painful. When he must be outside in the wind, he lays bricks without a garment. His belt is a cord for his back, a string for his buttocks. His strength has vanished through fatigue and stiffness, kneading all his excrement. He eats bread with his fingers, although he washes himself but once a day.

“It is miserable for the carpenter when he planes the roof-beam. It is the roof of a chamber 10 by 6 cubits. A month goes by in laying the beams and spreading the matting. All the work is accomplished. But as for the food which is to be given to his household (while he is away), there is no one who provides for his children.”

More Jobs from “Satire of the Trades”

“The Satire of the Trades” from “ Instruction of Dua-Khety” from the Middle Kingdom (2050- 1710 B.C.) continues: “The vintner carries his shoulder-yoke. Each of his shoulders is burdened with age. A swelling is on his neck, and it festers. He spends the morning in watering leeks and the evening with corianders, after he has spent the midday in the palm grove. So it happens that he sinks down (at last) and dies through his deliveries, more than one of any other profession.

Ancient Egyptian mail

“The fieldhand cries out more than the guinea fowl. His voice is louder than the raven's. His fingers have become ulcerous with an excess of stench. When he is taken away to be enrolled in Delta labour, he is in tatters. He suffers when he proceeds to the island, and sickness is his payment. The forced labour then is tripled. If he comes back from the marshes there, he reaches his house worn out, for the forced labor has ruined him.

“The weaver inside the weaving house is more wretched than a woman. His knees are drawn up against his belly. He cannot breathe the air. If he wastes a single day without weaving, he is beaten with 50 whip lashes. He has to give food to the doorkeeper to allow him to come out to the daylight. The arrow maker, completely wretched, goes into the desert. Greater than his own pay is what he has to spend for his she-ass for its work afterwards. Great is also what he has to give to the fieldhand to set him on the right road to the flint source. When he reaches his house in the evening, the journey has ruined him.

“The courier goes abroad after handing over his property to his children, being fearful of the lions and the Asiatics. He only knows himself when he is back in Egypt. But his household by then is only a tent. There is no happy homecoming. The furnace-tender, his fingers are foul, the smell thereof is as corpses. His eyes are inflamed because of the heaviness of smoke. He cannot get rid of his dirt, although he spends the day at the reed pond. Clothes are an abomination to him. The sandal maker is utterly wretched carrying his tubs of oil. His stores are provided with carcasses, and what he bites is hides.

“The washerman launders at the riverbank in the vicinity of the crocodile. I shall go away, father, from the flowing water, said his son and his daughter, to a more satisfactory profession, one more distinguished than any other profession. His food is mixed with filth, and there is no part of him which is clean. He cleans the clothes of a woman in menstruation. He weeps when he spends all day with a beating stick and a stone there. One says to him, dirty laundry, come to me, the brim overflows.

“The fowler is utterly weak while searching out for the denizens of the sky. If the flock passes by above him, then he says: would that I might have nets. But God will not let this come to pass for him, for He is opposed to his activity. I mention for you also the fisherman. He is more miserable than one of any other profession, one who is at his work in a river infested with crocodiles. When the totalling of his account is made for him, then he will lament. One did not tell him that a crocodile was standing there, and fear has now blinded him. When he comes to the flowing water, so he falls as through the might of God.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024