Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

UPPER CLASSES IN ANCIENT EGYPT

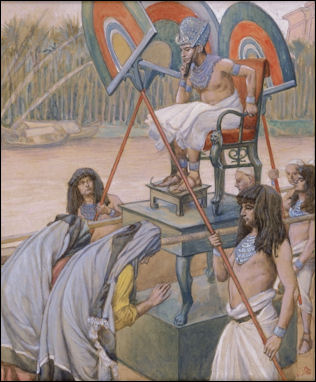

Tissot's Pharaoh and

the Midwives Egyptian society was stratified into a small elite and a large number of commoners. Excavations of tombs have shown clear differences between the elite and non-elite. Commoners were often buried en masse in shallow pits while the rich buried in elaborate tombs with pots, plates, vases, beads, bracelets and cosmetic holders. Nancy Lovless, a Canadian anthropologist working at a cemetery from 2,300 B.C., told Reuter: "So far it does look as if elite people did have much better health. We have clear stratification here."

The upper classes consisted of landowners, scribes, priests, administrators and military officers. The goal of society was centered at maintaining the order of the universe to ensure a favorable position in the afterlife. The New Kingdom's affluent and fashion-conscious elite were arguably the world’s first leisure class. Noblemen were carried around in litters. Necklaces of precious stones were worn by both sexes. The teeth of the rich were often full of cavities, which indicates they may have ate lots of dates and honey. Their bones are generally less scared and more delicate.

The case of Weni the Elder is often offered as evidence that merit was rewarded in ancient Egypt. According to an inscription he lived around 2200 B.C. and rose from humble birth to become an advisor of three kings and the “True Governor of Upper Egypt.

Texts like “The Story of Sinuhe,” “The Eloquent Peasant,” “The Report of Wenamun , “The Tale of Woe,” and The Teaching of Ankhsheshonq” are interesting stories in their own right but also offer invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian society and the daily life or ordinary Egyptians.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Society” by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian State: The Origins of Egyptian Culture (c. 8000–2000 BC)” by Robert J. Wenke (2009) Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

“The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Culture Revealed” by Moustafa Gadalla (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Burden of Egypt” by John A. Wilson (1951) Amazon.com;

“Through a Glass Darkly: Magic, Dreams and Prophecy in Ancient Egypt” (2023)

by Kasia Szpakowska (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

“Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohs” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen (2009) Amazon.com;

Commoners and Slaves in Ancient Egypt

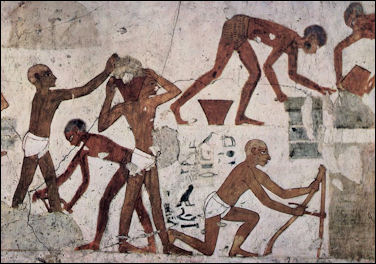

The pyramid builders are regarded as good examples of Egyptian commoners. They lived in crowded, dirty villages consisting of mud brick houses with thatched roofs, some of which had a bakery in the back room. Men wore loin clothes and women dressed in long sheaths attached above the breasts with a shoulder strap. Children went nude until they were teenagers.

brick making In ancient times, Egyptian commoners showed respect to people of superior castes by crawling on their stomachs. The teeth of the non-elite were worn down from eating course bread. They suffered from anaemia and had thick bones, more arthritis (indication of hard work) and more fractures and scars that members of the upper classes.

Ordinary houses were built of mud brick which eventually crumbled and washed away.

The ancient Egyptians kept slaves. Many of them were captives of wars. Some pharaohs had court dwarves and pet pygmies.

As urban life developed, society became more complex. In the past people lived around villages or farms and grew little more food than they could consume themselves and traded very little partly because there was nobody to trade to. As populations became large and more centralized, there was more people to trade to. Thus there was an incentive for farmers to produce surpluses and sell them and tradesmen to produce other goods to trade with them.

As society became more complex there were different trades and the interrelation between them became more complex too. By the time the Babylonians were dominate there were three distinct classes: 1) nobles with hereditary estates; 2) freemen, who could own land but not pass it on to their children; and 3) slaves.

See Separate Article: SLAVERY IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Herodotus on Egyptian Society

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “The Egyptians are divided into seven classes: priests, warriors, cowherds, swineherds, merchants, interpreters, and pilots. There are this many classes, each named after its occupation. The warriors are divided into Kalasiries and Hermotubies, and they belong to the following districts (for all divisions in Egypt are made according to districts). 165. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

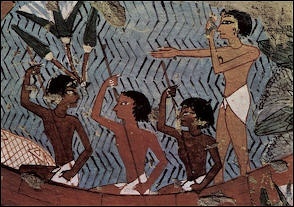

granary

“The Hermotubies are from the districts of Busiris, Saïs, Khemmis, and Papremis, the island called Prosopitis, and half of Natho—from all of these; their number, at its greatest, attained to a hundred and sixty thousand. None of these has learned any common trade; they are free to follow the profession of arms alone. 166.

“The Kalasiries are from the districts of Thebes , Bubastis, Aphthis, Tanis, Mendes, Sebennys, Athribis, Pharbaïthis, Thmuis, Onuphis, Anytis, Myecphoris (this last is in an island opposite the city of Bubastis — from all of these; their number, at its greatest, attained to two hundred and fifty thousand men. These too may practise no trade but war, which is their hereditary calling. 167.

“Now whether this, too, the Greeks have learned from the Egyptians, I cannot confidently judge. I know that in Thrace and Scythia and Persia and Lydia and nearly all foreign countries, those who learn trades are held in less esteem than the rest of the people, and those who have least to do with artisans' work, especially men who are free to practise the art of war, are highly honored. This much is certain: that this opinion, which is held by all Greeks and particularly by the Lacedaemonians, is of foreign origin. It is in Corinth that artisans are held in least contempt. 168.

“The warriors were the only Egyptians, except the priests, who had special privileges: for each of them an untaxed plot of twelve acres was set apart. This acre is a square of a hundred Egyptian cubits each way, the Egyptian cubit being equal to the Samian. These lands were set apart for all; it was never the same men who cultivated them, but each in turn.69 A thousand Kalasiries and as many Hermotubies were the king's annual bodyguard. These men, besides their lands, each received a daily provision of five minae's weight of roast grain, two minae of beef, and four cups of wine. These were the gifts received by each bodyguard. 169.

Wealthy People and Elites in Ancient Egypt

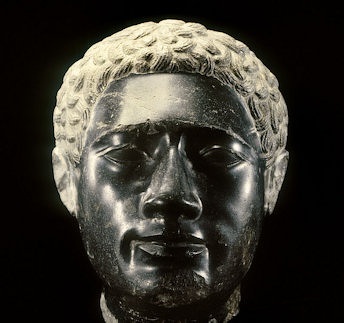

priest, often a member of the upper class

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: :Archaeology provides evidence of wealthy, and moderately wealthy, rural and urban dwellers, whose villas and mansions, both at Amarna and elsewhere, had storage capacities that exceeded the needs of single nuclear families. These individuals (in some cases they seem to have been wealthy farmer s) probably provided grain to extended networks of relations, including kin, clients, etc. Especially from the 7 th century BCE on, a new kind of prestigious habitat, the so-called tower-house, spread in Lower Egypt and the Fayum area and constituted in some cities distinctive neighborhoods. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“During the Old and Middle Kingdoms several archives and royal decrees deal with the organization of cult, priestly organization, and revenue derived from royal funerary temples. These particular sanctuaries appear as centers where the central and provincial elites met together, participated in ritual services, and probably thereby strengthened their consciousness of being part of the ruling elite. As sources of income, authority, and social influence, priestly positions could be bought and sold; moreover, many such positions were restricted by royal order for members of the elite. Provincial temples too, though less satisfactorily documented, played a crucial role as bases of author ity, prestige, and income for local potentates and their families. Significantly, they also were key centers that put into contact the local elites, the court, and the king through land donations, the foundation of royal chapels, and the erection of royal statues.

“Local elites could thus enlarge their political horizons and become more integrated into the government apparatus controlled by the monarchy and preserve their own interests, while at the same time be officially recognized by the k ing as key local agents, to the detriment of other, rival families. The strategies developed by some of the best-documented families , including the choice of prestigious zones wherein to build their necropoleis, reveal the complex interplay of these factors and their political and economic impact.”

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: At Tell Edfu in southern Egypt, in a large villa dating to the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (ca. 1500–1450 B.C.), archaeologists have found evidence of the rise and fall of an elite couple. Near a small fireplace and offering table, they discovered objects including a carved limestone stela of a man and woman standing together. On the stela’s frame, hieroglyphic text identifies the man with the titles mayor and overseer of priests, the most important positions in the administration of Tell Edfu and its temple. This couple and their descendants, all of whom inhabited the villa, were members of an important family at a time when the rulers in the capital city of Thebes sought to consolidate their power by forging alliances with nobles in the south. At some point, the couple’s faces and names were hacked away for unknown reasons. “Somehow these family members had fallen out of favor, and their names were removed from the collective memory,” says Egyptologist Nadine Moeller, director of the University of Chicago’s Tell Edfu Project. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

Sattjeni, Wife a Governor and Member of the Ancient Egyptian Elite

A coffin, discovered in 2016 in the necropolis at Qubbet el-Hawa across the Nile River from Aswan by a team led by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, an Egyptologist at the University of Jaén in Spain., belonged to an important local woman, Sattjeni, daughter of one governor, wife of another and mother of two more. Sattjeni's mummified body was buried in two cedar coffins made of wood imported from Lebanon. She was not a royal, but her family practiced royal strategies to hold on to their governing power: She married her sister's widower, and her family was associated itself with the ram-headed deity Khnum. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, June 6, 2016 |~|]

Jiménez-Serrano told livescience: “Qubbet el-Hawa is one of the most important nonroyal necropolises of ancient Egypt. Its importance lies in the great quantity and quality of the biographical inscriptions carved in the façades of the funerary complexes. The necropolis was mainly used to bury the highest officials of the nearby town of Elephantine, the capital of the southernmost province of Egypt, at the end of the third millennium and the beginning of the second (2200 B.C. to 1775 B.C). The governors were buried together with their relatives; the members of their courts (officials and domestic service) were buried in other smaller and less-decorated tombs. Thus, today, we know the existence of 100 tombs, of which only 80 have been completely cleared. |~|

“During the Middle Kingdom, especially during the 12th Dynasty (1950 B.C. to 1775 B.C.), the governors of Elephantine built giant funerary complexes in the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa. Some of them are beautifully decorated and have important inscriptions....Sattjeni was the second daughter of one of the most important figures of the 12th Dynasty, the governor Sarenput II. Unfortunately, her brother Ankhu died shortly after his father, and there were no male successors. So she and her sister Gaut-Anuket had the rights of the rule in Elephantine. The latter married a certain official called Heqaib and converted him into the new governor of Elephantine: Heqaib II. However, we suspect that Gaut-Anuket did not live much time, because Sattjeni married Heqaib II. They had at least two children, who became the governors of Elephantine successively, as Heqaib III and Ameny-Seneb. |~|

“This discovery shows that the local dynasties of the periphery of the State emulated the royal family. In this concrete case, we can confirm that women were the holders of the dynastic rights. Probably, the members of these families married as the royal family — brother with sister — in order to keep the divine blood "pure." We must not forget that Sattjeni's family declared themselves heirs of a local god.” |~|

Servants in Ancient Egypt

From picture from Tell el Amarna we can see in what grand style an Egyptian lord lived, and we may be sure that he required a vast number of servants. Our knowledge of these dependants is gleaned chiefly from the details that we have of the courts of the nomarchs of the 12th dynasty. The chief of the household consisted of an old “superintendent of the provision house," who had the charge of the store-rooms. He had the supervision of the bakery as well as of the slaughter-house, and grew so stout in the exercise of his duties that at the funeral festival of his master he was not able to carry his own offering. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

At the head of the kitchen stood the “superintendent of the dwelling; “''' the serfs were subject to him; the “superintendent of the bakehouse'' governed the bakery and the “scribe of the sideboard “' was originally appointed to take charge of his master's drinks. To these we must add the porter, the baker, the gardener, and other under-scrvants, as well as handicraftsmen and women who worked for the master. Smaller households under the Middle Kingdom were arranged of course in a more modest manner, yet they often had their serfs,' bakers,' and other servants, who were certainly some of them bond-servants; there were also female slaves: pretty Syrians were often chosen to wait on the master.

In the royal court at any rate there were bond-servants, who were under their “great superintendent "; and amongst the upper servants of the household there were certainly many foreign imported slaves. But these royal “provision superintendents," “superintendents of the dwelling," serfs, “bearers of cool drinks," '' “scribes of the sideboard," “preparers of sweets," as they are called, were people of importance and respectability, and the more so because the Egyptians at all times were very fond of good cooking.

Internal Hierarchy in Ancient Egyptian Villages

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The often assumed image of villages as egalitarian paradises must be discarded, with no traces of communal property within them. Instead, the most ancient sources reveal that they were characterized by internal hierarchies and inequalities of wealth. Village governors are their best documented members, frequently evoked in administrative records because of their role as intermediaries between the authorities and the mass of villagers. Such a strategic position procured them some advantages: they acted as informal agents of the crown in the countryside, and their collaboration was essential for delivering taxes and manpower to the state. In some instances, their position was symbolically enhanced by the possession of prestige items usually restricted to the palatial and administrative elite of the kingdom. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Old Kingdom sources refer to them as HoA njwt, “governor of a locality,” but later they are commonly called HAtj-a, “mayor” (nA HAtjw-a nA dmjw wHywt, “the mayors of the towns and villages”: Gardiner 1947: 31*). Other members of the village elite were the priests and scribes; in the case of the household (pr.s, “her house”) of the lady Tepi, quoted in the Gebelein papyri, it was made up of a scribe, a letter carrier (jrj mDAt), and a “property manager” (jrj jxt; Posener-Kriéger and Demichelis 2004: pl. 16H). In other cases, wealthy peasants appear in charge of the property of the temples, delivering taxes in gold or possessing enough resources to rent extensive tracts of land, like some jHwtjw of the New Kingdom and some nmHw in the 1st millennium B.C.. One such New Kingdom jHwtj, Horiherneferher, was one of the notables (rmT aA, “great people”) of his village in the famous lawsuit of Mose.

“In general, archaeology reveals the existence of such social differences through the goods buried in private tombs, and the information it provides confirms the picture shown by administrative documents. Finally, local priestly offices (especially low ranking functions like wab) not only conferred prestige and served to visualize and consolidate social hierarchies, but could also be used as a means of self-promotion thanks to the contacts, patronage links, and income they procured. Local notables are referred to as rmT aA, “great people,” from the late New Kingdom on.”

Integration of Diverse Communities in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The integration of different communities in cosmopolitan settings, such as capital cities and probably also in lesser cities” is an interesting topic. “One is reminded of the famous stela depicting an Asiatic soldier drinking beer in the company of his (apparently) Egyptian wife and young son. Some documents refer to Asiatics as prisoners of war or slaves in the hands of institutions. But in other instances they appear to have been well integrated in pharaonic society, married Egyptians, performed various trad es, bore Egyptian titles occasionally and displayed their foreign origin in their otherwise fully Egyptian monuments. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Thus, for instance, Perseneb, an attendant of the palace, bore an Egyptian name, but his grandmother, his two sisters, and other members of his household were presented in his monuments as Asiatics (aAmw ), while his niece bore a non-Egyptian name. The Wilbour Papyrus provides evidence of foreigners who had become soldiers a nd officials in the Egyptian army and who enjoyed considerable wealth as holders of substantial plots of land. There is, furthermore, evidence of military colonies where Asiatic soldiers were settled in Ramesside times, especially in Middle Egypt. We are, however, unaware of whether Asiatics living in Egyptian cities settled in separate neighborhoods or, on the contrary, whether they mingled with their Egyptian neighbors in the same urban sectors.

“Bietak has recently shown that Egyptians living in Avaris during the Hyksos Period occupied a particular area of the city, judging from the material evidence: neither toggle-pins nor intramural burials have been found there (two typical Canaanite ethnic markers), while these items were prese nt in neighboring quarters. It might then be inferred that this part of the city was inhabited by an Egyptian community. Other foreign settlers entering the Nile Valley seem to have preferred (or been forced into) a segregated life according to the funerary evidence.

“Such is the case regarding the Pan-Grave Nubian cemeteries, dating to the first centuries of the second millennium BCE, recovered in many localities of Upper Egypt. It does appear that people from different origins co existed at specific sites such as at harbors and mining centers. Slaves and serfs arrived in Egypt in substantial numbers during some periods. Usually employed in dome stic activities in private households or as specialized workers (weavers, cultivators, gardeners) in institutions, they may have constituted another social sector in cities and in the rural domains of the nobility. It is unknown to what extent the mix of s laves, soldiers, and traders from different countries may have contributed to create some sort of “creole” culture in those places. Their presence may have introduced foreign rituals and fashions that exerted some influence on their humbler Eg yptian neighbors, or conversely may have strengthened a sense of Egyptian-ness among the Egyptian population.”

Cultural Changes in Rigid Ancient Egyptian Society

Nathaniel Scharping wrote in Discover: “The importance of hierarchy is reinforced, a dominant theme of Egyptian society, throughout the corpus of writings. An entire class of writing called “teachings” was dedicated to imparting wisdom and morality, and often included instructions on how to act around those of different social classes.... The role of the king in maintaining the balance of the universe was heavily emphasized, as well. Taken together, the writings paint a picture of a society permeated almost completely by the influence of the pharaoh. [Source: Nathaniel Scharping, Discover, September 22, 2016 =]

Toby Wilkinson, an Egyptologist at the University of Cambridge, “identifies a clear shift in perspective as time goes on. Writings in archaic Egyptian meant for the priests and nobles give way to plain-language compositions that reflect the broadening influence of the middle class. One such example of a composition with a clear preference for plain language is “The Great Hymn to the Orb,” written during the reign of Akhenaten from 1353-1336 B.C. in the 18th Dynasty. =

“It praises the sun, characterized here as a deity in its own right:

“You shine forth in beauty on the horizon of heaven,

O living Orb, the creator of life!

When you rise on the eastern horizon,

You fill every land with your beauty.

Beautiful, great, dazzling,

High over every land,

Your rays encompass the lands

To the limit of all that you have made.

For you are the sun, you have reached their limits,

You subdue them for your beloved son.

You are distant (yet) your rays are upon the earth.

You are in (every) face (yet) your movements are unseen.”

[Source: The text of “The Great Hymn to the Orb” inscribed inside the tomb of Ay at Amarna]

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.)

The Instruction of Ptahhotep is an ancient Egyptian literary composition written by the Vizier Ptahhotep, during the rule of King Izezi of the Fifth Dynasty. Regarded as one of the best examples of wisdom literature, specifically under the genre of Instructions that teach something, of Ptahhotep addresses various virtues that are necessary to live a good life in accordance with Maat (justice) and offers insight into Old Kingdom — and ancient Egyptian — thought, morality and attitudes. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) begins: “The prefect, the feudal lord Ptah-hotep, says: O Ptah with the two crocodiles, my lord, the progress of age changes into senility. Decay falls upon man and decline takes the place of youth. A vexation weighs upon him every day; sight fails, the ear becomes deaf; his strength dissolves without ceasing. The mouth is silent, speech fails him; the mind decays, remembering not the day before. The whole body suffers. That which is good becomes evil; taste completely disappears. Old age makes a man altogether miserable; the nose is stopped up, breathing no more from exhaustion. Standing or sitting there is here a condition of . . . Who will cause me to have authority to speak, that I may declare to him the words of those who have heard the counsels of former days? And the counsels heard of the gods, who will give me authority to declare them? Cause that it be so and that evil be removed from those that are enlightened; send the double . . . The majesty of this god says: Instruct him in the sayings of former days. It is this which constitutes the merit of the children of the great. All that which makes the soul equal penetrates him who hears it, and that which it says produces no satiety. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“Beginning of the arrangement of the good sayings, spoken by the noble lord, the divine father, beloved of Ptah, the son of the king, the first-born of his race, the prefect and feudal lord Ptah-hotep, so as to instruct the ignorant in the knowledge of the arguments of the good sayings. It is profitable for him who hears them, it is a loss to him who shall transgress them. He says to his son:

“Be not arrogant because of that which you know; deal with the ignorant as with the learned; for the barriers of art are not closed, no artist being in possession of the perfection to which he should aspire. But good words are more difficult to find than the emerald, for it is by slaves that that is discovered among the rocks of pegmatite.

“If you find a disputant while he is hot, and if he is superior to you in ability, lower the hands, bend the back, do not get into a passion with him. As he will not let you destroy his words, it is utterly wrong to interrupt him; that proclaims that you are incapable of keeping yourself calm, when you are contradicted. If then you have to do with a disputant while he is hot, imitate one who does not stir. You have the advantage over him if you keep silence when he is uttering evil words. "The better of the two is he who is impassive," say the bystanders, and you are right in the opinion of the great.

“If you find a disputant while he is hot, do not despise him because you are not of the same opinion. Be not angry against him when he is wrong; away with such a thing. He fights against himself; require him not further to flatter your feelings. Do not amuse yourself with the spectacle which you have before you; it is odious, it is mean, it is the part of a despicable soul so to do. As soon as you let yourself be moved by your feelings, combat this desire as a thing that is reproved by the great.

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on Leadership and Rulers

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “If you have, as leader, to decide on the conduct of a great number of men, seek the most perfect manner of doing so that your own conduct may be without reproach. Justice is great, invariable, and assured; it has not been disturbed since the age of Ptah. To throw obstacles in the way of the laws is to open the way before violence. Shall that which is below gain the upper hand, if the unjust does not attain to the place of justice? Even he who says: I take for myself, of my own free-will; but says not: I take by virtue of my authority. The limitations of justice are invariable; such is the instruction which every man receives from his father. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“Inspire not men with fear, else Ptah will fight against you in the same manner. If any one asserts that he lives by such means, Ptah will take away the bread from his mouth; if any one asserts that he enriches himself thereby, Ptah says: I may take those riches to myself. If any one asserts that he beats others, Ptah will end by reducing him to impotence. Let no one inspire men with fear; this is the will of Ptah. Let one provide sustenance for them in the lap of peace; it will then be that they will freely give what has been torn from them by terror. “If you are among the persons seated at meat in the house of a greater man than yourself, take that which he gives you, bowing to the ground. Regard that which is placed before you, but point not at it; regard it not frequently; he is a blameworthy person who departs from this rule. Speak not to the great man more than he requires, for one knows not what may be displeasing to him. Speak when he invites you and your worth will be pleasing. As for the great man who has plenty of means of existence, his conduct is as he himself wishes. He does that which pleases him; if he desires to repose, he realizes his intention. The great man stretching forth his hand does that to which other men do not attain. But as the means of existence are under the will of Ptah, one can not rebel against it.

Thutmose III

“If you are one of those who bring the messages of one great man to another, conform yourself exactly to that wherewith he has charged you; perform for him the commission as he has enjoined you. Beware of altering in speaking the offensive words which one great person addresses to another; he who perverts the trustfulness of his way, in order to repeat only what produces pleasure in the words of every man, great or small, is a detestable person.

“If you are employed in the larit, stand or sit rather than walk about. Lay down rules for yourself from the first: not to absent yourself even when weariness overtakes you. Keep an eye on him who enters announcing that what he asks is secret; what is entrusted to you is above appreciation, and all contrary argument is a matter to be rejected. He is a god who penetrates into a place where no relaxation of the rules is made for the privileged.

“If you are with people who display for you an extreme affection, saying: "Aspiration of my heart, aspiration of my heart, where there is no remedy! That which is said in your heart, let it be realized by springing up spontaneously. Sovereign master, I give myself to your opinion. Your name is approved without speaking. Your body is full of vigor, your face is above your neighbors." If then you are accustomed to this excess of flattery, and there be an obstacle to you in your desires, then your impulse is to obey your passion. But he who . . . according to his caprice, his soul is . . ., his body is . . . While the man who is master of his soul is superior to those whom Ptah has loaded with his gifts; the man who obeys his passion is under the power of his wife.

“Declare your line of conduct without reticence; give your opinion in the council of your lord; while there are people who turn back upon their own words when they speak, so as not to offend him who has put forward a statement, and answer not in this fashion: "He is the great man who will recognize the error of another; and when he shall raise his voice to oppose the other about it he will keep silence after what I have said."

“If you are a leader, setting forward your plans according to that which you decide, perform perfect actions which posterity may remember, without letting the words prevail with you which multiply flattery, which excite pride and produce vanity. “If you are a leader of peace, listen to the discourse of the petitioner. Be not abrupt with him; that would trouble him. Say not to him: "You have already recounted this." Indulgence will encourage him to accomplish the object of his coming. As for being abrupt with the complainant because he described what passed when the injury was done, instead of complaining of the injury itself let it not be! The way to obtain a clear explanation is to listen with kindness.

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on Being a Loyal Subject

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “If you are a farmer, gather the crops in the field which the great Ptah has given you, do not boast in the house of your neighbors; it is better to make oneself dreaded by one's deeds. As for him who, master of his own way of acting, being all-powerful, seizes the goods of others like a crocodile in the midst even of watchment, his children are an object of malediction, of scorn, and of hatred on account of it, while his father is grievously distressed, and as for the mother who has borne him, happy is another rather than herself. But a man becomes a god when he is chief of a tribe which has confidence in following him. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“If you abase yourself in obeying a superior, your conduct is entirely good before Ptah. Knowing who you ought to obey and who you ought to command, do not lift up your heart against him. As you know that in him is authority, be respectful toward him as belonging to him. Wealth comes only at Ptah's own good-will, and his caprice only is the law; as for him who . . Ptah, who has created his superiority, turns himself from him and he is overthrown.

“Be active during the time of your existence, do no more than is commanded. Do not spoil the time of your activity; he is a blameworthy person who makes a bad use of his moments. Do not lose the daily opportunity of increasing that which your house possesses. Activity produces riches, and riches do not endure when it slackens.

“If you are a wise man, bring up a son who shall be pleasing to Ptah. If he conforms his conduct to your way and occupies himself with your affairs as is right, do to him all the good you can; he is your son, a person attached to you whom your own self has begotten. Separate not your heart from him.... But if he conducts himself ill and transgresses your wish, if he rejects all counsel, if his mouth goes according to the evil word, strike him on the mouth in return. Give orders without hesitation to those who do wrong, to him whose temper is turbulent; and he will not deviate from the straight path, and there will be no obstacle to interrupt the way.

“If you desire to excite respect within the house you enter, for example the house of a superior, a friend, or any person of consideration, in short everywhere where you enter, keep yourself from making advances to a woman, for there is nothing good in so doing. There is no prudence in taking part in it, and thousands of men destroy themselves in order to enjoy a moment, brief as a dream, while they gain death, so as to know it. It is a villainous intention, that of a man who thus excites himself; if he goes on to carry it out, his mind abandons him. For as for him who is without repugnance for such an act, there is no good sense at all in him.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024