Home | Category: Language and Hieroglyphics

PAPYRUS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

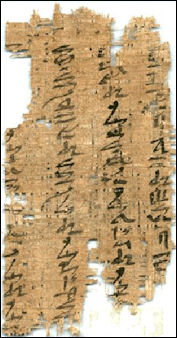

Papyrus Harrageh Unlike the Mesopotamians who wrote on clay tablets, the Egyptians wrote on papyrus, a brittle paper-like material made from reeds of Nile sedge (a grass-like plant), which were moistened, pounded, smoothed, dried, and pressed woven together like a mat. The word paper is derived from papyrus. Strong enough to endure for millennia and be discovered by archaeologists, papyrus is thicker and heavier than modern paper but good quality and good for writing. Ostraca was a kind of papyrus made of left over stone chips.

Papyrus is light and strong and ideal for writing on. The ancient Egyptians wrote with reed styluses that were not all that different from quill pens used until the 19th century. Scribes used a palate with a slit for storing styli and separate wells for red and black ink. Black ink was made from lampblack and water. The Egyptians built papyrus libraries in 3200 B.C. Some papyrus rolls were 133 feet long.

Michael Schmidt, the author of books about poets and director of the Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University in England, has Schmidt has noted that the fine grain of papyrus promoted the development of writing because it gave ''the ability to vary letter-forms.'' Many modern words for books descend from antiquity, when papyrus scrolls — some up to 100 yards long — were used for storage. A ''volume'' (from the Latin volumen) literally means ''a thing rolled up.''

There is a such a thing as a field of papryology. The largest papyrus collection in the world is at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. Much of the work in the field consists of piecing together fragments of papyrus of Egyptian, Greek and Latin texts, often using the handwriting of individual scribes as the primary clue. One project involved painstakingly piecing together 50,000 scraps of private record like tax receipts. After a century the project was about 5 percent complete.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World”

by Irene Vallejo (2022) Amazon.com;

“Papyrus” by John Gaudet (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day” The Complete Papyrus of Ani Featuring Integrated Text and Full-Color Images, Illustrated, by Dr. Raymond Faulkner (Translator), Ogden Goelet (Translator), Carol Andrews (Preface) (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Papyrus Ebers: Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by Cyril P. Bryan (Translator) 2021) Amazon.com;

“The Westcar Papyrus" (a well-known papyrus). Amazon.com;

Things Made from Papyrus

The direction followed by the mechanical arts of a place is essentially determined by the materials found in that place. It was of the greatest consequence for Egyptian industrial arts that one of the most useful plants the world has ever known grew in every marsh. The papyrus reed was used as a universal material by the Egyptians, like the bamboo or the coconut palm by other places; it was the more useful as it formed a substitute for wood, which was never plentiful. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

From the papyrus, boats were manufactured," mats were plaited, rope was twisted, sandals were prepared; but above all the papyrus supplied the material for paper. Papyrus served for the preparation of rough mats and ropes, though for this purpose they also possessed another excellent material in palm bast. In the plaiting of these mats, which were indispensable to spread over the mud floors of Egyptian houses, they were evidently very skilful; this is shown by the stripes of rich ornamentation found particularly on the ceilings of the tombs, which doubtless originally represented a covering of matting. "

The examples already shown will give an idea of the kind of work referred to here. Bright colors were always employed; the same style and coloring may also be seen in the pretty baskets brought to our museums from the Theban tombs; these are plaited in patterns of various colored fibres. "

History of Papyrus in Ancient Egypt

Magical papyrus boxes The Egyptian learned to make papyrus by 3000 B.C. or earlier. A blank role of papyrus was found sealed in a tomb, perhaps as old as 3200 B.C. First papyrus with writing dates to 2500 B.C. Papyrus was widely used until the A.D. 8th century. Thanks to the dry climate some of ancient Egyptian documents written on papyrus survive today.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Papyrus was very important to the ancient Egyptians. It helped transform Egyptian society in many ways. Once the technology of papyrus making was developed, its method of production was kept secret allowing the Egyptians to have a monopoly on it. The first use of papyrus paper is believed to have been 4000 B.C. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Papyrus sheets are the earliest paper-like material – all other civilisations used stone, clay tablets, animal hide, wood materials or wax as a writing surface. Papyrus was, for over 3000 years, the most important writing material in the ancient world. It was exported all around the Mediterranean and was widely used in the Roman Empire as well as the Byzantine Empire. Its use continued in Europe until the seventh century AD, when an embargo on exporting it forced the Europeans to use parchment. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Papyrus was employed throughout the Classical Period and beyond until superseded by paper in around A.D. 800. Bridget Leach of the British Museum wrote: “A Blank papyrus roll found in the Early Dynastic tomb of Hemaka at Saqqara dating from approximately 3,000 B.C. attests to the early use of the plant to manufacture a material clearly intended for writing. It was used throughout Dynastic and Ptolemaic and Roman times and into the Byzantine and early Islamic Periods until it was gradually superseded by paper. The latest extant papyrus is an Arabic document from 1087 CE. Some of the best known examples are the finely illustrated funerary papyri such as The Book of the Dead of Any from the New Kingdom. Papyrus was used for a wide variety of documents, administrative records, and letters, as well as didactic, literary, or medical texts. There is no account describing the papermaking process itself until Pliny (the Elder) provided one in Roman times. [Source: Bridget Leach, British Museum, London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Nile Sedges, the Source of Papyrus

papyrus plant

The Nile sedge is the largest member of the sedge family. The plant has a graceful flowing head and stems that can reach 15 feet in length and a six inches in width. The "bulrushes" that Moses was born among were most likely papyrus plants. Papyrus flower crowns were worn by Roman diplomats.

Scarce in Egypt today but still found in abundance in Sudan and Uganda, the sedges were collected by ancient Egyptians who split them into 12-inch-long strips that were soaked in river water. After the skin was removed, the inner pith was split into strips which were placed together, in slightly overlapping horizontal and vertical strips, and pressed until the papyrus strips dried and were bound together by natural glues in the plants. The sheets were then burnished with clay powder until smooth.

The Egyptian also used the Nile sedge to make sandals, twine, mats, cloth, building materials, fuel, life preservers, boats and clothing. Bouquets of papyrus flowers were left on Egyptian tombs. Huts were made of bundled papyrus supports. Papyrus stalks were used in a religious ceremony honoring Hathor, the goddess of love. Columns were modeled on papyrus stems.

The papyrus plant — Cyperus papyrus — grew along the Nile in ancient times. According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: ““This plant was quite versatile and was not only used in the production of paper but it was also used in the manufacture of boats, rope and baskets. However, the singularly most important and valuable product was the papyrus paper. Not only was this ancient Egypt’s greatest export but it revolutionized the way people kept valuable information. No substitution for papyrus paper could be found that was as durable and lightweight until the development of pulped paper by the Arabs. The way of making pulp paper was far easier to produce but not as durable. This not only led to a decline in papyrus paper making, but also to a decline in the papyrus plant cultivation. Eventually, the papyrus plant disappeared from the area of the Nile, where it was once the lifeblood for ancient Egypt.[Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Bridget Leach of the British Museum wrote: “The botanical name given to the plant is Cyperus papyrus L.. It belongs to the large Cyperaceae family of sedge plants, Cyperus being the genus name and papyrus the species; the ‘L’ refers to the name of the Swedish botanist Linnaeus, who first classified it in 1753. The plant grows to about four meters high and has a tall, green triangular shaped stem, which is wide at the base and tapers to the top where it separates into a wide flower-head or umbel. At its base, the stem is approximately five to eight centimeters thick. The stem encases the papyrus pith, from which the writing material is made and in which fibers are embedded that carry nutrients from the roots to the umbel. The pith, or parenchyma, is cream colored with a spongy texture and a high cellulose content, but the fibers are woody or ligneous; thus, the plant is very suitable for producing sheets of paper as the fibers give rigidity and the pith substance to the manufactured sheet.[Source: Bridget Leach, British Museum, London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“In antiquity, papyrus grew plentifully in Egypt along the Nile Valley, and the art of ancient Egypt shows numerous paintings of rural scenes in which the plant is seen growing in the river marshland. Today it grows in central and east Africa and parts of the Mediterranean, including Sicily.”

Papyrus Making

men splitting papyrus

To make papyrus, the papyrus reeds were pulled up by the stalks in the marshes by laborers who according to tomb images worked nude and afterwards brought the bundles to the workshops tied up in bundles. To make paper from papyrus reeds, the stem was cut into thin strips of the length required, and a second layer of similar strips was then placed crosswise over these; the leaves thus formed were then pressed,' dried, and, if a larger piece were required, pasted together. Sheets of papyrus were made by gluing the mats together. Scrolls were made my gluing sheets together. When dried out papyrus naturally curled up which is why most ancient literary works were in the form of scrolls. Scrolls were fairly durable but frequent rolling and unrolling caused the written words to wear off.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Papyrus making was not revived until around 1969. An Egyptian scientist named Dr. Hassan Ragab reintroduced the papyrus plant to Egypt and started a papyrus plantation near Cairo. He also had to research the method of production. Because the exact methods for making papyrus paper was such a secret, the ancient Egyptians left no written records as to the manufacturing process. Dr. Ragab finally figured out how it was done, and now papyrus making is back in Egypt after a very long absence. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The Method of Papyrus Paper Production: 1) The stalks of the papyrus plant are harvested. 2) Next the green skin of the stalk is removed and the inner pith is taken out and cut into long strips. The strips are then pounded and soaked in water for 3 days until pliable. 3) The strips are then cut to the length desired and laid horizontally on a cotton sheet overlapping about 1 millimeter. Other strips are laid vertically over the horizontal strips resulting in the criss-cross pattern in papyrus paper. Another cotton sheet is placed on top. 4) The sheet is put in a press and squeezed together, with the cotton sheets being replaced until all the moisture is removed. 5) Finally, all the strips are pressed together forming a single sheet of papyrus paper.” +\

Bridget Leach of the British Museum wrote: “Pliny’s account of making paper from papyrus is generally accepted although some details remain unclear. However, examination of the ancient material and experiments have established the basic principles of manufacture. The lower, and therefore wider, part of the stem is used as it contains the most pith. A length of between 20 and 30 centimeters is cut off and the outer rind peeled off. The pith is then sliced longitudinally to produce strips, which are laid side by side to form one layer; more strips are then placed on top at right angles to form a second layer. The whole is then beaten or pressed together to form a homogeneous sheet, which is then dried. Aided by the natural sap contained in the plant, the pressure applied during this procedure fuses the cellulose in each layer together physically and chemically, in a similar way to the formation of modern paper. [Source: Bridget Leach, British Museum, London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ] “Individual sheets of papyrus were then joined together to form rolls using a starch-based paste . A study by Basile and Di Natale (1999) of the preparation of the papyrus surface for writing found coatings including egg, gum, and milk on several ancient samples. In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, state control was clearly a significant factor in papyrus production. It is difficult to imagine that this was substantially different in the preceding periods, but we lack documentation or evidence. Papyrus was certainly a valued material as the number of palimpsests from Dynastic Egypt shows. Papyrus (especially the study rind or epiderm) was also used to make rope, sandals, and other everyday objects.”

Ancient Egyptian Papyrus Trade

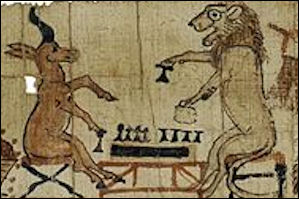

Satirical papyrus Numberless papyri, of which some are as old as the early 26th century B.C., , testify to the perfection attained in this manufacture, even at an early date. During Greco-Roman times, papyrus was one of Egypt's chief articles of export. Papyrus was highly valued as testified by the fact that Egyptians often made use of each roll several times by washing off the former writing, and secondly, for rough drafts or unimportant matters they made out with a cheaper writing material such as potsherds or pieces of limestone. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Exports of papyrus-paper, beginning around 3000 B.C., earned Egypt a considerable income. Large factories churned out rolls 20 to 45 meters long and recycled papyrus was used to make mummies and pasteboard for coffins. Papyrus was so valuable the process for making it was a carefully guarded secret until it was revealed by Pliny the Elder in 77 A.D.

During Hellenistic times papyrus was displaced by parchment and vellum, materials made from bleached, stretched animal hides. Velum was more durable that papyrus, plus it could be rolled up and could be creased or made into a book. But papyrus paper-making enduring to the 9th century A.D. when it was replaced by paper made from linen using a technique developed by the Chinese around 100 A.D.

Animal skin parchment came into widespread use in the 3rd or 4th century A.D. True paper, made by grinding and mashing fibers into a soupy mixture and then spreading them across a screen to dry, was not introduced to the Middle East and Europe until the Middle Ages

World’s Oldest Papyri — the Diary of Merer

The world’s oldest known papyri with text is the Diary of Merer (also known as Papyrus Jarf) — papyrus logbooks written over 4,500 years ago by Merer, a middle-ranking official with the title of inspector. They date to the 27th year of the reign of Pharaoh Khufu (reigned c. 2589–2566 B.C.), the builder of the largest pyramid at Giza, during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt. The text is written with hieratic hieroglyphs and mostly consists of lists of the daily activities of Merer and his crew. The best preserved sections (Papyrus Jarf A and B) document the transportation of white limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to Giza by boat. [Source Wikipedia]

The Diary of Merer is part of a group of papyri sometimes called Red Sea Scrolls. There are several types of documents among the Red Sea Scrolls, but the writings of Merer caused the most excitement as Merer kept records in his diary of a team involved in the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The first batch of Red Sea Scrolls was found on March 24, 2013 near the entrance to the storage space designated G2. The second and largest set of documents was found 10 days later, wedged between blocks in storage space at Hong Kong. Archaeologists found hundreds of papyrus fragments in the caves at Wadi al-Jarf. Written in black and red ink, the texts mention Pharaoh Khufu. Many of these fragments have been pieced back together to form documents — some measuring two feet long! The fragment of Merer’s journal shown here is from Papyrus B. Kong. [Source: José Miguel Parra, National Geographic, February 23, 2024]

The logbooks contain records detailing the construction of the largest pyramid of Giza and were discovered at the Red Sea harbor of Wadi al-Jarfin in 2013. Merer was "in charge of a team of about 200 men,"archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard wrote in an article published in 2014 in the journal Near Eastern Archaeology. Tallet and Marouard wrote: "Over a period of several months, [the logbook] reports — in [the] form of a timetable with two columns per day — many operations related to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza and the work at the limestone quarries on the opposite bank of the Nile."[Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science July 19, 2016 ^^^]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: “Merer recorded the logs in the 27th year of Khufu's reign. His records say that the Great Pyramid was near completion, with much of the remaining work focusing on the construction of the limestone casing that covered the outside of the pyramid, Tallet and Marouard wrote. The limestone used in this casing, according to the logbook, was quarried at Tura near modern-day Cairo, and was brought to the pyramid site by boat along the Nile River and a system of canals. One boat trip between Tura and the pyramid site took four days to complete, the logbook notes. ^^^

See Separate Article: MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com

World's Oldest Book — Papyrus Tax Record of Beer and Oil

Ilana Herzig wrote in Archaeology magazine: A 10-by-6-inch piece of papyrus is, researchers now believe, part of the world’s first book. And, like many of the volumes that fill offices, libraries, and homes, it has had many lives. The papyrus fragment, which was unearthed along with hundreds of other pieces of papyrus at the site of El Hibeh in 1902, began as a bound document dating to 260 B.C. that recorded taxation rates for beer and oil scrawled in Greek letters using black ink. The sheet was then removed from its binding and sent as a letter before being transformed once again when its painted with images, including one depicting a son of the falcon-headed god Horus, and reused as wrapping for a mummy during the Ptolemaic period (304–30 B.C.). [Source: Ilana Herzig,Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

Using microscopic and multispectral imaging, a team led by conservator Theresa Zammit Lupi of the University of Graz learned how the book was made. “You have a plain sheet of papyrus, folded in two, written on, and turned into a booklet,” says Zammit Lupi. “The different bifolios, or single sheets folded in the center, were attached via tackets, flexible material used to join two things together, similar to a modern ring binder.”

The presence of holes for the tackets to pass through, a handful of which still have remnants of thread, and the symmetrical ink transfer across the precise fold at the center, confirmed that the bifolio had once been bound within an ancient manuscript. “An accountant must have detached the bifolio from the book, folded and sealed the letter, and then passed it on to a creditor or a debtor,” says Zammit Lupi. The discovery pushes the origins of bookbinding back by centuries. “The oldest book previously known was from the first or second century A.D., so this predates anything by up to 400 years,” Zammit Lupi says. “The book could be indicative of how transactions happened, of how people lived, wrote, and passed information to each other. Most importantly, we learned that the structure of the book, as opposed to a scroll, existed well before we thought.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except men splitting papyrus, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024