Home | Category: Language and Hieroglyphics

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN WRITING

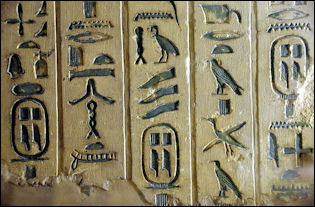

pyramid texts The Egyptians were one of the earliest people to develop a writing system. Their writing system was totally different from the one we use today. Instead of letters in an alphabet they used pictures and symbols that we call “hieroglyphics.” The word “ Hieroglyph” is Greek for "sacred writing." This a reference to the fact that the ancient Egyptians believed that the knowledge of writing was something that was bestowed from Thoth, the God of Knowledge.

From the earliest ages the Egyptians had the greatest veneration for their writing, which they considered to be the foundation of all education. They called it the divine words, and believed it to have been an invention of the god Thoth, who had taught it to the inhabitants of the Nile valley.

Ancient Egypt writing — and also reading — was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties. Some of the earliest writing was done on perishable papyrus. Much of has this been lost to time.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms” by Andrew Robinson Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Language and Writing: The History and Legacy of Hieroglyphs and Scripts in Ancient Egypt” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Hieratic Texts; 1: 1 by Sir Alan Henderson Gardiner (1879-1963) Amazon.com;

“A Miscellany of Demotic Texts and Studies (The Carlsbert Papyri, 3)”

by Paul John Frandsen and Kim Ryholy (2000) Amazon.com;

“Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs” by James Peter Allen (2000) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Practical Guide” by Janice Kamrin (2004) Amazon.com;

“How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs” by Mark Collier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hieroglyphs Without Mystery” by Karl-Theodor Zauzich (1992) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Complete Beginners: The Revolutionary New Approach to Reading the Monuments” by Bill Manley (2012) Amazon.com;

“Hieroglyphic Dictionary: A Vocabulary of the Middle Egyptian Language” by Bill Petty (2012) Amazon.com;

“Illustrated Hieroglyphics Handbook” by Ruth Schumann Antelme (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Amarna Scholarly Tablets” by Shlomo Izre'el (1997) Cuneiform Tablets in Egypt Amazon.com

Types of Ancient Egyptian Writing

The ancient Egyptians also developed "an abbreviated 'long hand' form of writing which we call 'hieratic.'" During the first millennium A.D. this abbreviated hieratic script was supplanted by a new form of short-form writing called "Demotic." Hieriatic has been described as cursive form of writing and “demotic” was a cursive form that could be written very quickly. They were written mostly on papyrus and were used mainly for private and business correspondence. The symbols were abbreviated hieroglyphics.

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science; Egyptian language changed over the millennia, with scholars often subdividing the surviving writings into categories such as "Old Egyptian," "Middle Egyptian" and "Late Egyptian." The Greek language became widely used in the time after Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great. In the late 19th century, archaeologists excavated half a million papyri fragments, most of which were written in Greek, at the ancient Egyptian town of Oxyrhynchus in southern Egypt, dating to the early centuries A.D. Coptic, an Egyptian language that uses the Greek alphabet, was widely used after Christianity spread throughout Egypt. As Greek and Coptic grew in popularity, the use of the hieroglyphic writing style declined and became extinct during the fifth century A.D. After A.D. 641 the Arabic language spread in Egypt and is widely used in the country today. [Source:Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

World's Oldest Writing

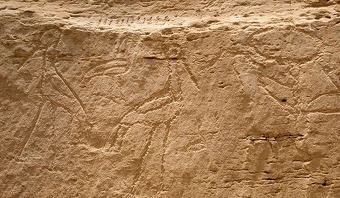

In 1995, John Coleman Darnell, a Yale Egyptologist, and his students discovered 18-x-20-inch tableau, dated to 3250 B.C., on a limestone cliff at a site called Gebel Tjauti, about 20 miles northwest of Luxor, that contains some line drawings of animals that are believed to be a record of the exploits of an Egyptian ruler. Because an image of a scorpion is present links to the Scorpion king were made. Some have even gone as far as calling the tableau “world’s oldest historical record” and claim the images are early hieroglyphics and are examples of the world’s oldest writing.

The tableau, probably incised with flint tools, has images of a scorpion, a falcon, large antelope, a bird, a serpent, a figure carrying a staff, a sedan chair, a bull’s head, a captor and captive. No one knows what the images mean. The link to the Scorpion King are based on the fact that the scorpion is near the falcon and falcons in ancient Egypt were associated with the god Horus and the pharaohs.

The earliest known public Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription contains four symbols: a bull’s head mounted on a pole, followed by two storks flanking an ibis. It is believed to be royal messaging. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: A team led by Darnell found the hieroglyphs on a cliff face within view of a desert road north of the ancient city of Elkab. Dating to around 3250 B.C., they were carved during Dynasty 0, a period when the Nile Valley was divided into competing kingdoms and scribes were just beginning to master writing. Previously discovered Dynasty 0 inscriptions are less than an inch in height and are largely confined to arcane administrative matters, but the newly discovered inscription is 27 inches tall, and is the earliest known set of large-scale, highly visible hieroglyphs by some 300 years. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2018]

“The inscription’s symbols — a bull’s head on a pole, followed by two storks and an ibis — are similar to those used in later Egyptian writing to equate a pharaoh’s authority with control over the cosmos. That led Darnell to conclude that the inscription was a royal boundary marker that asserted a king’s dominion over the area. “It was like a signpost,” says Darnell. “Travelers along that road would have known they were entering an area under official authority.” In addition, he believes the discovery suggests that Egyptian writing developed at a quicker pace than previously thought, and was being used to publicly project royal power at a very early date.

See Separate Article: WORLD'S OLDEST RECOGNIZED WRITING: DEBATE AND CANDIDATES africame.factsanddetails.com

Oldest Names and Alphabet

The world's oldest surviving personal name is a king represented by the hieroglyphic sign of a scorpion on a Upper Egypt tablet from 3,050 B.C. Some scholars have suggested that the king's name was Sekhen.

In the second millennium B.C. Semitic tribes converted Egyptian hieroglyphics into the first alphabet. Some graffiti with letters, dated to around 1800 B.C., found in southern Egypt, has been offered as evidence of the first alphabetic writing. The graffiti was dated based on nearby hieroglyphics and is theorized to have been made by an ancient Semitic people. What the symbols mean is not clear and whether there are indeed alphabetic letters is a matter of some debate. They predate other examples of alphabetic writing by two centuries.

See Separate Article: WORLD’S OLDEST ALPHABETS AND ALPHABETIC WRITTEN LANGUAGES africame.factsanddetails.com

Variety and Expressiveness of Ancient Egyptian Writing

Andreas Pries wrote:Among the idiosyncratic aspects of ancient Egyptian life and culture, Egyptian writing has long received particular attention — not only in recent academic discourse, but already in Antiquity. Compared to other writing systems, hieroglyphs and, to a lesser extent, their cursive derivatives, hieratic and Demotic, demonstrate extraordinary potential to express different aspects of both meaning and sound when employed beyond their conventional use. [Source:Andreas Pries, University of Tübingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

In its particular iconicity Egyptian writing, especially hieroglyphic writing, works even outside the framework of language and shares common features with Egyptian art. In the textual record non-standard creative writings highlight the potency and multidimensionality of Egyptian writing through the interplay of meaning, sound, and icon. The main characteristics of non-standard creative writings defined according to their varying forms and functions. In conclusion, a system of classification, as provided here, can further our understanding of the multitude of forms and functions involved, and thereby enhance appreciation of the potency of Egyptian writing.

Early Greek historians (or rather, ethnographers) and philosophers were captivated by the fact that different types of writing were in use in Egypt at the same time to serve different purposes and to function even in an iconic, extra-linguistic context. Particularly, although not exclusively, the hieroglyphic script and its strong iconicity (or rather, pictoriality; for the difference between the two categories, were main topics of interest.

The various scripts of genuine Egyptian origin all represent a logo-phonetic writing system that consists of phonetic, logographic, and classifier signs and thus combines the expression of meaning and sound. On that note, the use of hieroglyphs, hieratic, and Demotic is aimed at both the semantic and the phonetic notation of language. Furthermore, there is no fixed orthography for Egyptian words, nor is there a limited inventory of signs. Theoretically, an indefinite number of new or modified signs could be added to this open inventory as long as their meaning is more or less self-evident to their recipients. But custom and tradition had a strong impact on what writings were possible in any given context and at any given time, though besides these standard writings the use of variant and also unconventional spellings is widespread.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Egyptian Writing: Extended Practices” by Andreas Pries escholarship.org

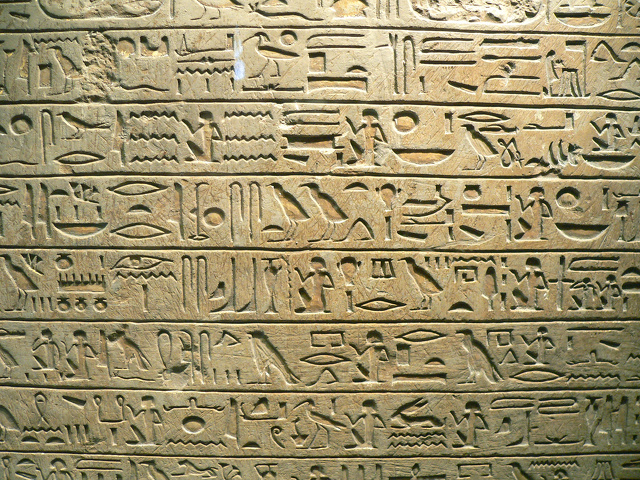

Hieroglyphics

Egyptian writing in the form hieroglyphics is associated most with inscriptions and writing on tomb and temple walls. Hieroglyphics function as both logograms (signs representing things or ideas) and phonograms (pictured objects represented sounds, similar to letters in an alphabet). They also served as word-signs (signs which stood for entire words) and syllabic signs (signs which stood for syllables). In Egyptian times syllables were not grouped into a single word as they are in English today. They were written separately as were words and thus sometimes distinguishing between a word and a syllable of a word was difficult. There were no hieroglyphic vowels.

Hieroglyphics primarily represented the formal and ceremonial language for the pharaohs. They appeared on everything: paintings, obelisks, temple walls, coffins, tombs, documents, perfume containers. An estimated one third of the 110,000 Egyptian pieces in the British Museum have writing on them.

Simon Singh of the BBC wrote: “Hieroglyphs dominated the landscape of the Egyptian civilisation. These elaborate symbols were ideal for inscriptions on the walls of majestic temples and monuments, and indeed the Greek word hieroglyphica means 'sacred carvings', but they were too fussy for day-to-day scribbling, so other scripts were evolved in Egypt in parallel. These were the 'hieratic' and 'demotic' scripts, which can crudely be thought of as merely different fonts of the hieroglyphic alphabet. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

See Separate Article: HIEROGLYPHICS africame.factsanddetails.com

Oldest Alphabetic Writing in Ancient Egypt

One of the oldest examples of alphabetic writing in ancient Egypt is on a limestone ostracon, dated 15th century B.C. found in Luxor, Egypt, measuring nine centimeters (3.54 inches) high, 8.5 centimeters (3.34 inches) wide, 2.3 centimeters (0.9 inches) thick. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

According to Archaeology magazine “The first alphabetic writing system was created in the Levant and Sinai Peninsula sometime in the second millennium B.C., probably between 1850 and 1700 B.C., by adapting Egyptian hieroglyphs — a writing system expressing both concept and sound — to represent only sound. This Proto-Sinaitic alphabet is the ancestor of many of the writing systems that developed across the world. Until now, the earliest known alphabet tables, called abecedaries, have been found on cuneiform tablets from Ugarit, in what is now Syria, dating to the thirteenth century B.C. But while studying an undeciphered ostracon found in a tomb at Luxor by Nigel Strudwick and his team from the Cambridge Theban Mission, Egyptologist Ben Haring of the University of Leiden discovered an abecedary that predates those tablets by two centuries, making it the oldest example ever found.

“The order of the symbols is not the “ABC” of Western alphabets, but, explains Haring, the h-l-h-m that is the beginning of the well-known order of alphabets of the ancient Near East. This was the clue Haring needed to recognize that this might be an abecedary used by scribes or for teaching purposes. These words have initial sounds that begin at the extreme right of the first four lines. The individual characters are used to form single consonants or sets of two consonants. “As preserved, there are 13 lines on the front and back of the ostracon,” says Haring. “If it were complete, there would have been anything between 25 lines, the number of consonants in the Egyptian hieroglyphic script, or 30 lines, which would represent the Ugaritic alphabet. But since it isn’t complete,” he says, “we don’t know if the alphabet expressed here is native Egyptian or foreign. If it’s Egyptian, it may imply an important role for Egypt in the development of the alphabet.”

See Separate Article: WORLD’S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITTEN LANGUAGES africame.factsanddetails.com

Development of Cursive Writing in Ancient Egypt

Even under the Old Kingdom a special cursive hand had already been invented for daily use, the so-called hieratic, in which the various hieroglyphs were gradually abbreviated more and more so as to be easily written. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Among the disadvantages of cursive characters were that they often obliterated the characteristic forms of the signs. For example, the letters d, t, and r were so much alike that most of the scribes of the New Kingdom failed to distinguish the one from the other. This was also the case with many other signs. Thus mistakes of all kinds crept in freely, and the Egyptians themselves often could not read correctly the pieces that they were copying.

The height of confusion was reached however, when the scribes who were employed in rapid business-writing began, from the time of the 20th dynasty, to cut short to a few strokes those words which occurred most frequently. The following examples will suffice to show how much this writings differed even from the older cursive hand.

These signs could be no longer really read, for no one could make out from these strokes and dots which hieroglyphs they originally represented. We have to take a group of signs as a whole, and to bear in mind that a perpendicular stroke with four dots is the sign for mankind, and so on. A few centuries later and this shortened form was developed into a new independent style of writing, the so-called demotic. If we reflect that the writing underwent this complete degeneration at the same time as the orthography also degenerated in the manner described above, we shall be able to imagine the peculiar character of many handwritings of later time.

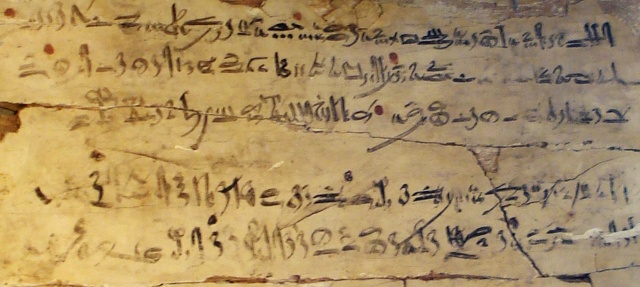

Hieratic Writing

The ancient Egyptians used hieratic written with ink and on papyrus paper for everyday communication, and for things like composing poems and stories, producing memoirs and wills and writing documents and personal letters. Although hieratic was easier to use they continued to use hieroglyphic pictures in their original forms. To make black ink they mixed vegetable gum, soot and bee wax. They replaced soot with other materials such as ochre to make various colours. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Ursula Verhoeven wrote: Hieratic is the name given to Egypt's oldest cursive system of hieroglyphs, which was used primarily as handwriting and served as a multifunctional script for more than three millennia, until the third century CE. As early as 1820, Champollion recognized the connection between hieroglyphs and hieratic. Hieratic was written in ink on papyrus and ostraca, as well as on wooden tablets, linen, stone surfaces, etc. The characters could also be carved or chiseled into clay, wood, rock surfaces, or stone objects. Unlike hieroglyphs, hieratic was always written from right to left, and the signs evolved from separate elements in single columns to horizontal lines of complete text, with increasing use of ligatures and abbreviations, especially in administrative contexts. In addition, most manuscripts reveal personal idiosyncrasies of the scribes. [Source: Ursula Verhoeven, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

From 750 B.C. on, hieratic was partially replaced by the abnormal hieratic script and later by Demotic. However, it remained in use until Roman times, primarily for ritual, funerary, and scientific texts. Increasingly enhanced by digital methods, the study of hieratic is based on paleographic analysis and comparison, which aid our understanding of the texts and allow us to date a manuscript or identify an individual scribe. Writing practices, the social milieu of scribes, and the various scripts, text genres, and modes of transmission have become current research topics. In addition, the discovery, decipherment, adequate documentation, and interpretation of other testimonies to hieratic writing are of interest.

Documents in mixed hieratic and Demotic served various purposes and included magical texts, instructional texts for learning signs and grammar, manuals for priests, onomastika, medical texts, etc.. The special appearance of Roman hieratic is due to the use of a new writing tool, the reed pen. The reed pen allowed for precise and uniform ink writing, as opposed to the older brushes or rushes, which produced a more fluid and pleasing handwriting with varying thicknesses of ink. The last papyri with hieratic (again partly mixed with Demotic) can be dated to the third century CE

Development of Hieratic Script

Hieratic could be carved into rocks or stone surfaces and is called lapidary or monumental hieratic. Inscriptions or graffiti of this type are mainly found on the mountains of Western Thebes, on routes in the Western Desert, or in the Wadi el-Hol. Stone roofs and walls of tombs and temples were also inscribed: see, e.g., the genealogy of 18 generations of priests during the 22nd to 24th Dynasties on a temple wall at Karnak. A few examples show incised hieratic on New Kingdom stelae: a fragment from Amara West/Nubia, dated to Seti I and Ramses II (1290-1213 B.C.), uses a hieroglyphic-hieratic mix of signs. [Source: Ursula Verhoeven, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

The origins of hieratic script can be traced back to late Old Kingdom when abbreviations of hieroglyphics began to appear slowly in administrative texts. These became widespread during the Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 B.C.) Such as in the Heqanakht Papyri, Reisner Papyri, and el-Lahun Papyri). Ligatures (cursive groups derived from two or more hieratic signs) , mostly between two or three, but also up to six signs, became increasingly common, especially from the 11th to 12th Dynasties (2105 to 1802 B.C.). Study of ligatures on New Kingdom ostraca was initiated by Annie Gasse (2018).

During the first millennium B.C., late hieratic returns to clearly recognizable characters with only a few ligatures and abbreviations, perhaps in deliberate contrast to the shorthand of cursive/abnormal hieratic and Demotic. In hieratic, the so-called alphabetic or single-consonant characters were most commonly used. The very common signs as well as the simple geometric signs presented no significant changes over the millennia. Here, each sign number is linked to a grapheme (representation of a phoneme or sound). The more complex graphemes, which a scribe did not need to write very often, show great differences in their hieratic design.

In famous literary papyri of the Middle Kingdom, the range of basic forms used for the various bird signs was apparently reduced to only eight basic forms. Some hieratograms are very similar in shape but completely different in their graphemic value. In practice, however, this was not a major problem, since these signs were always complemented by phonetic signs or unambiguous classifiers.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Hieratic” by Ursula Verhoeven escholarship.org

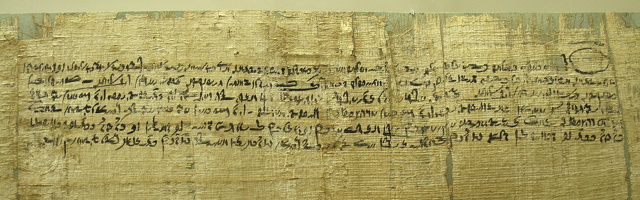

Demotic Script

Demotic is the ancient Egyptian script derived from northern forms of hieratic used in the Nile Delta. The term was first used by the Greek historian Herodotus to distinguish it from hieratic and hieroglyphic scripts. By convention, the word "Demotic" is capitalized in order to distinguish it from demotic Greek. [Source Wikipedia]

The Demotic script was referred to by the Egyptians as “document writing”. It was used for more than a thousand years, and during that time a number of developmental stages occurred. It is written and read from right to left, while earlier hieroglyphs could be written from top to bottom, left to right, or right to left. Parts of the Demotic Greek Magical Papyri were written with a cypher script.

Egyptian demotic script was used for "the contemporary language used in everyday speech as well as administrative documents," Foy Scalf, head of research archives and a research associate at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, told Live Science. [Source Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, July 24, 2022]

Demotic is on the Rosetta along with hieroglyphics and Greek. In contrast, "the grammar of the hieroglyphic section imitates Middle Egyptian," the phase of the Egyptian language associated with Egypt's Middle Kingdom period, which spanned from about 2044 B.C. to 1650 B.C., Scalf told Live Science. "By the Ptolemaic period, Middle Egyptian was often used for very formal inscriptions, as Egyptian scribes considered it a classical version of their language whose imitation added authority to the text."

Like its hieroglyphic predecessor script, Demotic possessed a set of "uniliteral" or "alphabetical" signs that could be used to represent individual phonemes. These are the most common signs in Demotic, making up between one third and one half of all signs in any given text. They included one-consonant signs with no associated vowels Foreign words are also almost exclusively written with these signs. Later (Roman Period) texts used these signs even more frequently.

Types of Demotic Script

Early Demotic developed in Lower Egypt during the later part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, particularly found on steles from the Serapeum of Saqqara. It is generally dated between 650 and 400 BC, as most texts written in Early Demotic are dated to the Twenty-sixth Dynasty and the subsequent rule as a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire, which was known as the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. After the reunification of Egypt under Psamtik I, Demotic replaced Abnormal Hieratic in Upper Egypt, particularly during the reign of Amasis II, when it became the official administrative and legal script. During this period, Demotic was used only for administrative, legal, and commercial texts, while hieroglyphs and hieratic were reserved for religious texts and literature.

Middle Demotic (c. 400–30 B.C. is the stage of writing used during the Ptolemaic Kingdom. From the 4th century BC onward, Demotic held a higher status, as may be seen from its increasing use for literary and religious texts. By the end of the 3rd century BC, Koine Greek was more important, as it was the administrative language of the country;

Demotic contracts lost most of their legal force unless there was a note in Greek of being registered with the authorities. From the beginning of Roman rule of Egypt, Demotic was progressively less used in public life. There are, however, a number of literary texts written in Late Demotic (c. 30 B.C.–A.D. 452). especially from the A.D. 1st and 2nd centuries.

Coptic

Tonio Sebastian Richter wrote: Coptic is the youngest written standard of the Egyptian language. Spelled with the characters of the Greek alphabet plus some extra signs, it was productively used for almost a thousand years, from the fourth to the fourteenth centuries CE, to record texts of a wide range of types and purposes, and is still being used in the liturgy of the Coptic church. Coptic texts have survived in enormous numbers and comprise literary, semi-literary, and documentary corpora in a range of dialects and genres. Analysis of salient grammatical features of the Coptic language elucidates both innovative and conservative features in comparison to those of its predecessor, Demotic. [Source:Tonio Sebastian Richter, Freie Universität Berlin,UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

The Verbal sentence patterns in Coptic was TAM — Tense-Aspect-Mood, , indicating narrative (past) tense as well as perfect. A light-verb construction was employed to integrate morphologically opaque verbs, such as borrowed verbs and verbs with more than three consonants. The Demotic perfective construction wAH(-jw) f-infinitive “he had already done,” attested from Early Demotic on, conflated morphologically and semantically with the conjugation-infinitive.

The Coptic verbal conjugation and the converted adverbial conjugation saw the rise,based on analogy, of an innovative second-person singular feminine pronoun. Clause formation includes the focalizing conversion of an information-structuring pattern — urning an independent clause into a thematic statement to be complemented by an adverbial phrase of rhematic rank In Coptic it is no longer a distinct morphologic pattern as it had been in Late Egyptian and Demotic but aligns with other (usually circumstantial or relative) converters.

The production of Coptic apocryphal texts has recently become a hot spot of Coptic literary stud. It includes Coptic “semi-literary” corpora such as school texts, magical texts, medical recipes and alchemical recipes. Some locations long known for yielding Coptic documentary texts have recently yielded bulks of new material, such as the Theban West Bank, including Hermonthis and the Bawit Monastery. Some rich but hitherto neglected places have garnered new scholarly attention, such as the Faiyum area, the town of Hermopolis, the town of Edfu/Apollonopolis Magna and the island of Elephantine. The corpus of Copticepigraphy, for the most part funerary stelae, has traditionally suffered from insecure provenance and unknown archaeological context due to undocumented excavations and sales.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Coptic” by Tonio Sebastian Richter escholarship.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024