Home | Category: Language and Hieroglyphics

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN LANGUAGE

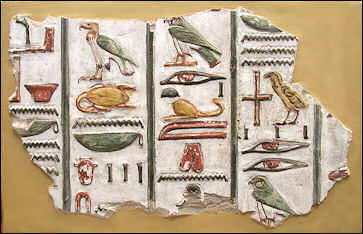

Hieroglyphics Even though scholars can read ancient Egyptian and they know that the Egyptian hieroglyphics are phonetic they are not exactly sure what the language sounded like. The ancient Egyptian language continued to be spoken until the Middle Ages. It remnants can be found in the liturgy of the Egyptian Coptic Church.

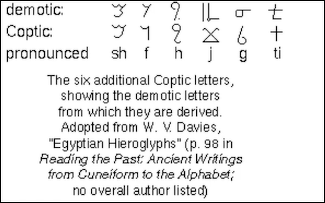

The Coptic language, the liturgical language of the Coptic church, probably became extinct in the 16th century. It had its own script and is regarded as the closest language to that of the Egyptian pharaohs. The Copts claimed descent from the ancient Egyptians; the word copt is derived from the Arabic word qubt (Egyptian). Egypt was Christianized during the first century A.D., when the country was part of the Roman Empire.

One pharaoh told his son in 2080 B.C.: "Be a craftsman in speech, [so that] though mayest be strong...the tongue is a sword...and is more valorous than any fighting." According to phoenicia.org: The ancient Egyptians attributed language to Taautos who was the father of tautology or imitation. Tradition says he invented the first written characters and came from Byblos, Phoenicia, the home of the one of the first alphabet. Taautos played his flute to the chief deity of Byblos who was a moon-goddess Ba'alat Nikkal. Taautos was called Thoth by the Greeks. The Egyptians called him Djehuti. Taautos — as well as Thoth and Dionysus — appear to have originated from Njörth, the snake priest who was, at times, was the consort to the moon-goddess. The snake priest was represented by the symbol of a pillar, a wand or a caduceus, which over time became the god Hermes or Mercury. The Greeks equated Thoth with the widely-traveled Hermes. [Source: phoenicia.org]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian” by Antonio Loprieno (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study” by James Peter Allen (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Phonology” by James Peter Allen (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Musical Aspects of The Ancient Egyptian Vocalic Language” by Moustafa Gadalla (2016) Amazon.com;

“Etymological Dictionary of Egyptian” by Gabor Takacs (1999) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Grammar” by Alan Gardiner (1927) Amazon.com;

“Fundamentals of Egyptian Grammar” by Leo Depuydt (1999) Amazon.com;

“Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs” by James Peter Allen (2000) Amazon.com;

“Middle Egyptian” by Peter Beylage (2018) Amazon.com;

Herodotus on Psammetichus’s Experiment on Language and Children

Psammetichus — better known today as Psamtik I — was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664–610 B.C. The great Greek historian Herodotus (484 – c. ... 425 B,C.) wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Now before Psammetichus became king of Egypt,the Egyptians believed that they were the oldest people on earth. But ever since Psammetichus became king and wished to find out which people were the oldest, they have believed that the Phrygians were older than they, and they than everybody else. Psammetichus, when he was in no way able to learn by inquiry which people had first come into being, devised a plan by which he took two newborn children of the common people and gave them to a shepherd to bring up among his flocks. He gave instructions that no one was to speak a word in their hearing; they were to stay by themselves in a lonely hut, and in due time the shepherd was to bring goats and give the children their milk and do everything else necessary. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Psammetichus did this, and gave these instructions, because he wanted to hear what speech would first come from the children, when they were past the age of indistinct babbling. And he had his wish; for one day, when the shepherd had done as he was told for two years, both children ran to him stretching out their hands and calling “Bekos!” as he opened the door and entered. When he first heard this, he kept quiet about it; but when, coming often and paying careful attention, he kept hearing this same word, he told his master at last and brought the children into the king's presence as required. Psammetichus then heard them himself, and asked to what language the word “Bekos” belonged; he found it to be a Phrygian word, signifying bread. Reasoning from this, the Egyptians acknowledged that the Phrygians were older than they. This is the story which I heard from the priests of Hephaestus'2 temple at Memphis; the Greeks say among many foolish things that Psammetichus had the children reared by women whose tongues he had cut out. 3.

Consonants and Vowels in the Ancient Egyptian Language

"Ancient Egyptian was a living oral language, and most hieroglyphs represent the sounds of consonants and certain emphatically expressed vowels," wrote Barry Kemp, a professor of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, England, in his book "100 Hieroglyphs: Think Like an Egyptian". [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

It may seem strange to us that Ancient Egyptian writing stopped half-way as it were, and did not indicate, by other signs, how the consonants were to be respectively vocalised, or whether they were to remain without vowels. When we understand however the construction of these languages, we see how it came to pass that the vowels had a secondary position. In the ancient Egyptian language the meaning of the word is generally contained in the consonants, whilst the vowels are added as a rule to indicate the grammatical forms. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Originally, therefore, the Egyptian writing consisted only of the following twenty-one consonants. Signs generally stood for a short word with similar sound, from which it derives its phonetic worth. The vowels of many words were simply omitted. In a few cases only, in which the vowel was really important for the right reading of the word, the Egyptians tried in a way to indicate the same in their writing. For this object they made use of the three consonants

Old Egyptian Language

James Allen of Brown University wrote: “Old Egyptian is the earliest stage of the ancient Egyptian language that is preserved in extensive texts. It represents a dialect as well as a historical stage of the language, showing grammatical similarities with and distinctions from later ones. One particular issue in studying Old Egyptian lies in the uneven nature of the Old Kingdom written record, which mostly consists of texts relating to the funerary domain. [Source: James Allen, Brown University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Old Egyptian is the name given to the stage of the ancient Egyptian language that is preserved in texts of the Old Kingdom. It is normally considered to begin with the inscriptions from the tomb of Metjen (early Dynasty 4, ca. 2575 B.C.), historically the first to contain more than the few words or phrases that are found in earlier sources. Its latest manifestations are in the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom— although the composition of at least some of these may in fact date to the end of the Old Kingdom (on the resulting linguistic layering in the Coffin Texts). Old Egyptian can be considered a dialect as well as a historical stage of Egyptian. Judging from its predominantly Memphite attestation, it probably represents a northern variety of the language. It shares with Late Egyptian a number of grammatical features that are absent in the intervening stage of Middle Egyptian. These suggest that Late Egyptian represents a related dialect, although it is primarily attested in Upper Egyptian sources.

“Old Egyptian was first codified as a distinct stage of the language in the middle of the twentieth century. The grammar of the Pyramid Texts has merited two independent studies, and the narrative verbal system of tomb biographies has been examined by Doret. A study of 4th Dynasty inscriptions specifically is Schweitzer. These are complemented by a number of smaller studies in journal articles, such as those of Edel and Schenkel’s studies of the Coffin Texts . Edel’s Altägyptische Grammatik remains the standard reference work for Old Egyptian, except for the verbal system, now supplemented by other studies, such as Allen, Doret, and Stauder. Particles are now discussed in Oréal.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Old Egyptian” by James P. Allen escholarship.org

Old Egyptian Sources

James Allen of Brown University wrote: “Most Old Egyptian texts were inscribed on stone in hieroglyphs; the accounts and non- royal letters were written in hieratic on papyrus, and the Coffin Texts exhibit a mixture of carved or painted hieroglyphs, cursive hieroglyphs, and hieratic on stone, wood, or papyrus. With the partial exception of some Coffin Texts, these sources exhibit a number of orthographic conventions different from those of later texts. [Source: James Allen, Brown University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

Old Egyptian texts consist primarily of tomb inscriptions. Those from non-royal tombs generally represent the genre known as tomb biographies, in which the deceased (usually in the first person) recounts his achievements and his deeds on behalf of the pharaoh. A few of these also preserve the text of letters received from the king, most notably those of Senedjemib Inti (Dynasty 5, Giza) Brovarski 2002: 89-110) and Harkhuf (Dynasty 6, Aswan: a letter of Pepi II). Royal tombinscriptions are primarily Pyramid Texts, a collection of rituals and magic spells inscribed in the pyramids of King Unas (Dynasty 5) and his successors of Dynasties 6 and 8. These are ancestral to the Coffin Texts; some of the spells in both corpora are identical, and other Coffin Texts are reedited versions of those from the Pyramid Texts. A number of royal decrees are also preserved.

“Representatives of other textual genres are minimal. These include accounts from royal funerary establishments of Dynasty 5, rock inscriptions, a few non-royal letters, and the dialogue and songs of workers depicted in non-royal tombs. A further source for the study of Old Egyptian is represented by personal names. Notably absent are “scientific” texts (medical and mathematical) and literary texts such as the stories and wisdom literature of the Middle Kingdom; although some of those are ascribed to Old Kingdom authors, they are composed in Middle Egyptian and preserved in manuscripts that date, at the earliest, to the Middle Kingdom. Translations of Old Egyptian texts include Strudwick (2005: tomb biographies and royal decrees), Allen (2005: Pyramid Texts), and Wente (1990: letters). Most Old Egyptian texts have been indexed lexically in the online Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptia (http://aaew2.bbaw.de/tla/index.html).

“The limited nature of this corpus presents some difficulties in the description of Old Egyptian grammar. Funerary texts can be suspected of language that is formalized and somewhat archaic; they contain virtually no narrative and little dialogue. Tomb biographies do contain narrative sequences but were composed as records of accomplishments rather than as historical narrations of past events. It is therefore difficult to determine, for instance, precisely how the language expressed the historical past as opposed to the perfect, if it made such a distinction at all. As an example, the tomb biography of Harkhuf expresses two commissions of the king in close succession with different forms of the same verb: jw hAb.n w Hm n mr.n-ra nb(.j) Hna (j)t.(j) … r jmAm and hAb w Hm.f m snnw zp wa.k: do these represent merely stylistic variants or a true grammatical contrast between historical perfect (“The Incarnation of Merenra, my lord, has sent me with my father … to Yam”) and past (“His Incarnation sent me a second time alone”)?

Old Egyptian Phonology

James Allen of Brown University wrote: “The phonemic inventory of Old Egyptian differs from that of its descendants in several respects . The consonants represented by the transcription symbols z and s (most likely [th] as in think and [s] as in sink, respectively), which are conflated (as s) in later stages, are still distinct. The historical derivation of T from k is evinced by pairs such as kw ~ Tw “you”, undoubtedly reflecting a process of palatalization and fronting: [ku] (or [kúwa]) [kyu] [tyu]. [Source: James Allen, Brown University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

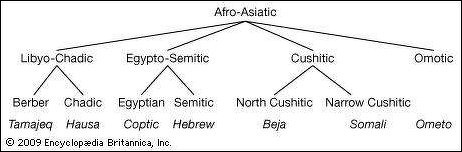

Ancient Egyptian language family tree

“Old Egyptian also demonstrates the derivation of S from X. These two consonants do not appear to be phonemically distinct, at least in the Pyramid Texts. Although some words are written only with the uniliteral signs for each (for example, Sj “lake” and Xt “belly”), some that later have X, such as pXr “go around,” are written with S (pSr), and some with both (such SAt and XAt “corpse,” later only XAt). A spelling such as SXAt—never the reverse, XSAt—both indicates that the š-sign had come to be pronounced as [š] in some words and signals that the older pronunciation of the sign was intended. Since both consonants are cognate with Semitic H (e.g., Hm ≈ Sm “father-in-law” and Hlo ≈ Xao “shave”), these phenomena apparently reflect a historical process of fronting and palatalization: H X ([xy]) and then, in some words, X S.

“A number of the sound changes that characterize later stages of the language are first attested in Old Egyptian. Depalatalization of T t appears a few times in late Dynasty 6. Loss of the feminine ending t occurs sporadically in attributives but is also suggested for nouns by the occasional use of a suppletive t in pronominal forms: e.g., mrt nb jrt.n stS “everything painful that Seth has done”.”

Lexical Morphology of Old Egyptian

“Unlike later stages of the language, Old Egyptian has the full range of six gender and number forms: masculine and feminine; singular, plural, and dual. The dual is still productive for nouns of all types—e.g., HfAwj “two snakes”—and not, as in Middle Egyptian, merely for those that typically appear in pairs. Adjectives show not only the three common forms—masculine singular, masculine plural, and feminine (singular)—but also occasional instances of the dual and feminine plural. Dual forms, obsolescent in Middle Egyptian, are attested for personal pronouns; when used attributively, the demonstratives pn/tn, pw/tw, and pf/tf have plurals formed with initial jp, obsolescent in later texts: jpn/jptn, jpw/jptw, and jpf/jptf (jpp- written jp). The stative may also have dual pronominal suffixes, at least for the third person feminine, and the third person plural distinguishes masculine and feminine in place of the unitary (masculine) suffix of Middle Egyptian. [Source: James Allen, Brown University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Second- and third-person singular independent pronouns are formed from their dependent counterparts (Tw/Tm → Twt/Tmt, sw/sj → swt/stt); the later forms consisting of jnt- plus a suffix pronoun are first attested at the end of Dynasty 6. The 1pl stative suffix is nw as well as the more common form in later texts, wjn. The neutral third-person pronoun st does not exist in Old Egyptian.

“One of the features that Old Egyptian has in common with Late Egyptian, but not Middle Egyptian, is gender and number concord between an initial nominal predicate and a following demonstrative subject (“copula”) in the non-verbal A pw construction: e.g., zA.k pw “he is your son,” jst tw “it is Isis,” msw nwt nw “they are Nut’s children”. The Middle Egyptian construction using the invariable masculine singular form of the demonstrative, however, also appears sporadically, as well as in the tripartite A pw B construction.”

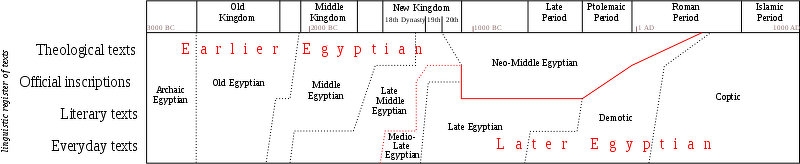

Egyptian lects

Old Egyptian Verb Forms

James Allen of Brown University wrote: “Old Egyptian exhibits the full range of synthetic verb forms (those distinguished by changes in the forms of a word), although one of these, the sDm.xr.f, is attested only once. Infinitival forms are the negatival complement, a number of verbal nouns, and the complementary infinitive. The first of these shows some evidence of being derived from a finite verb form through omission of an expressed subject: e.g., m jmk ~ m jmk.k “don’t rot” ~ “don’t you rot”, the second of these peculiar to Old Egyptian. Verbal nouns have four forms: the verb root (e.g., Htp) and the root plus the endings -t, -w or -y, and -wt or -yt (e.g., Htpt, Htpw and Htpy, Htpwt). The first two are used, for different verbs, in the paradigm of the infinitive, but it is not certain that a distinct infinitive existed as such, as least in the Pyramid Texts. The first and third forms (Htp and Htpw) characterize the complementary infinitive, which is used to reinforce a verbal predicate based on the same root. [Source: James Allen, Brown University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Finite nominal forms are the active and passive participles and the sDmtj.f or “verbal adjective” . Forms are generally the same as in Middle Egyptian with the exception of the geminated 2-lit. passive participle (e.g., xmm “unknown”), which is more common than in later texts. As in Middle Egyptian, the sDm.f and sDm.n.f can be used in attributive function; when they receive endings reflecting the gender and number of their antecedent, they are commonly known as relative forms. The active participle and the relative sDm.f and sDm.n.f of some verbs occasionally have prefixed forms; prefixed examples of the first two appear sporadically in Middle Egyptian and more frequently again in Late Egyptian.

“The imperative has singular and non- singular forms, as in Middle Egyptian; the latter has the ending -y in the Pyramid Texts and elsewhere also -w as in Middle Egyptian. Prefixed forms are common, as in Late Egyptian; a few are also attested in Middle Egyptian. The stative also has occasional prefixed forms; these disappear in later stages of the language. The category of the suffix conjugation comprises six or seven forms: active sDm.f, passive sDm.f, sDm.n.f, sDm.jn.f, sDm.xr.f, sDm.kA.f, and sDmt.f, the last probably an infinitival form rather than a finite one. Prefixed forms are attested for the active sDm.f and the sDm.n.f; these are absent in later stages of the language except for rare examples of the prefixed sDm.f in Middle Egyptian.”

Coptic language, still used by Copts in Egypt, developed from ancient Egyptian

Late Egyptian

Jean Winand wrote: Late Egyptian, the language of ancient Egypt during the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period, is attested in written form in a large array of literary and non-literary genres, mainly in the hieratic script on papyri and ostraca, but also in hieroglyphic monumental epigraphy. Late Egyptian is the first stage of the second major phase of Egyptian, according to the widely accepted division of the history of the language into Earlier and Later Egyptian. Typologically, Late Egyptian reflects major differences with respect to earlier stages of the language. Being more analytical in character, Late Egyptian thus displays a marked tendency to separate morphological from lexical information. It also tends to be more explicit in the articulation of sentences at the macro-syntactic level (Conjunctive and Sequential) and more time-oriented in its system of grammatical tenses than the aspect-oriented system of Classical Egyptian. [Source: Jean Winand, Université de Liège, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018]

Late Egyptian had basically two constructions for expressing sequentiality: the so-called Sequential pattern and the Conjunctive. The two constructions can be contrasted as regards their respective aspectual, temporal, and modal values. Fundamentally, the Sequential expressed a state of affairs that happened once (perfective) in the past, and whose truth-value could be ascertained (indicative). It was thus exclusively found in narrative. The Conjunctive was used to add (in a rather cumulative manner) actions without necessarily considering their chonological sequence. It was used in discourse and in future-oriented contexts, most frequently in letters wherein instructions were given after an imperative or a future III. By contrast, when used in narrative, the Conjunctive, in opposition to the Sequential, could express an activity that could be repeated (imperfective) and whose truth-value could not be plainly ascertained.The future was mainly expressed by the Future III.

It is important to note that Late Egyptian, in contrast to Earlier Egyptian, tended to match forms and functions one-to-one. For instance, Middle Egyptian could appear in autonomous sentences, in circumstantial clauses to express anteriority, in narrative to express sequentiality, or with emphatic function. In Late Egyptian, these four functions are assumed by different tenses/patterns. Due to phonetic evolution, some constructions superficially appeared to conflate into one, as was the case for the circumstantial Present I, the Sequential, and the Future III. Indeed it would be more accurate to state that the ambiguity could only exist in Late Egyptian.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Late Egyptian” by Jean Winand orbi.uliege.be

Language Issues in the New Kingdom

As ancient Egyptian writing consisted of consonants, the old orthography held on for a long time. Great confusion began however, when from the beginning of the New Kingdom many of the final consonants of the spoken language were either dropped or changed, without the people being courageous enough to forsake the former orthography, which had become quite obsolete. From this time, as centuries elapsed, the scribes more and more lost the consciousness that the letters which they wrote ought to signify certain phonetic signs. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Also during the New Kingdom, there were issues resulting from the difference betwee the languages of religious and official texts. Whilst the spoken language of the time (the New Egyptian) was commonly used from the beginning of the 18th dynasty for the writing of everyday life, it was thought necessary that the official and religious texts should be kept in the ancient language. The Old Egyptian plays the same part during the New Kingdom as Latin did in Europe during the Middle Ages, with this difference that the Old Egyptian was misused in far worse manner than the New Egyptian. The incoherence which reigns in many of these texts defies all description; it is so bad that it strikes even us, who know so little of the old language. This applies not only to those Egyptian texts, which were composed during the New Kingdom, but also to the far more ancient religious books in the handwriting of the New Kingdom, which are often so bad that we can only conclude that the scribes did not at all understand what they were copying.

Other nations have succeeded comparatively well in the experiment of employing and carrying on an ancient language, because they sought the assistance of grammars and lexicons; we are forced to conclude on the other hand that the Egyptians, who failed so completely, studied little or no grammar. In fact, no fragment of a lexicon or of a grammar has yet been found in any Egyptian papyrus. They did indeed write expositions of the sacred books, but as far as we can see from the commentaries that have come down to us, these were concerned with the signification of the matter of the contents, and did not discuss the meaning of the words; it was indeed impossible to do so, for the words appeared differently in every manuscript.

Relationship Between Egyptian and Neighboring African Languages

Julien Cooper wrote: Northeast Africa is dominated by two linguistic macrofamilies, Afroasiatic, with its constituent branches of Egyptian, Semitic, Berber, Kushitic, Chadic, and Omotic, and the Nilo-Saharan languages, with the most relevant phylum being the Eastern Sudanic branch spread across the Sahel and East Africa. On present research, there is evidence for contact between ancient Egyptian and ancient Berber, Kushitic, and Eastern Sudanic languages, with possibilities of contact with Ethiosemitic languages (the Semitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea). Evidence of Egypt’s contact with neighboring peoples in Northeast Africa is well established from the archaeological record and historical texts, especially along the Middle Nile (Nubia). [Source: Julien Cooper, Yale University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

comparison of ancient Egyptian and the Wolof language spoken in Senegal, the Gambia and Mauritania

The use of linguistic material, including loanwords and foreign names, for reconstructing ancient phases of contact between Egyptians and neighboring peoples is a relatively “untapped” source. The lexical data demonstrates a great familiarity and exchange between Egyptian and neighboring languages, which, in many cases, can be attributed to specific historical phases of contact through trade, expeditionary ventures, or conflict. Impediments remain in reconstructing the ancient “linguistic map” of neighboring Africa and our reliance on modern dictionaries of African languages for identifying ancient loanwords. Despite this, the stock of foreign words in the Egyptian lexicon is incredibly important for piecing together this “map.” In many cases, the ancient Egyptian lexicon contains the earliest data for foreign languages like Meroitic, Beja, or Berber.

Egyptian was written in a modified Egyptian script from the second century B.C. until possibly the early fifth century CE. There is reason to suspect that this language or a highly related one was spoken along the Nile in Upper Nubia from the second millennium B.C.. Some “Meroitic” personal names are known from the 17th-Dynasty papyrus Moscow 314. Indeed, the onomastic material from the Middle Kingdom Execration Texts relating to Kush and Sai Island resembles the phonological repertoire of an Eastern Sudanic language like Meroitic (Rilly 2006 – 2007), making it likely that the people of Kerma spoke a form of this language from at least around 1800 B.C.

It would be impossible to accurately define the extension of this language-group without more evidence, but it is likely that this language did not dominate Lower Nubia, a region defined by a very different linguistic group and archaeological culture in the C-Group. The current migratory model has Meroitic displacing a number of other Eastern Sudanic or Kushitic languages along the Nile, and it is tempting to link the arrival of Meroitic with a change in the repertoire of Egyptian place-names for Upper Nubia.

In the Old Kingdom, the Upper Nubian region was defined by the place-names ZATw, JrTt, and possibly JAm. In later periods these place-names are sparingly used in stereotyped contexts and largely replaced by the word “Kush” (Egyptian KS, Meroitic qes), a seemingly indigenous word for the polity and peoples of Upper Nubia (Kerma being its first capital), later extending towards Napata and Meroe. The Old Nubian language, the literary tongue of the Christianized Nubian kingdoms, has a debated history in this scheme. Like Meroitic, it is a Northern Eastern Sudanic language, and its nearest relatives in the Nuba mountains of Kordofan suggest it arrived at the Nile from the west and south. Texts in Old Nubian are largely known from the ninth century CE; the earliest, from Wadi el-Sebua, dates to 795 CE.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Egyptian Among Neighboring African Languages” by Julien Cooper

Language Contact with Ancient Egypt

Thomas Schneider wrote Although language contact and multilingualism are universal phenomena, the topic has not been given due consideration in Egyptology. Language contact in ancient Egypt comprises a spectrum, in ascending order, of small-scale phenomena (loanwords, loan translations), through non-Egyptian texts in Egyptian script and the evidence for bilingualism and multilingualism, to the large-scale phenomena of new language forms resulting from language contact and phenomena of language convergence through a sprachbund situation. [Source:Thomas Schneider, University of British Columbia, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2022]

idea that there was a primeval language

Persian terms in ancient Egyptian documents are rare. From the 14 attested words only a few occur before the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. The term Abjkrm “penalty” demonstrates the role that Aramaic played in linguistic transfer — attested in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, it seems a new adoption into Egyptian of Aramaic ’b(y)grn, the rendering of Old Persian abigarana-, ultimately harking back to the Persian codification of Egyptian law under Darius I. A Median (rather than Old Persian) title, vastra-bara “chamberlain”, is attested in the early Demotic transcription ws br.

Texts of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods also show definitive evidence for Egyptian-Proto-Berber language contact. The clearest example is (tA-)mrt “chin; beard,” Demotic mr , Coptic SBmort, Fmalt < Berber (ta-)mart “beard.” The preserved ending –t in the Egyptian forms shows that this must be a late loan. The words for “date” and “date palm,” in turn, have been proposed to be Proto-Berber loans from Egyptian, pointing to the introduction of date-palm cultivation from Egypt: Berber tiyni “date”< Egyptian bny(.t), Coptic SbNne. There are a significant number of Egyptian loanwords in Greek, some of which likely derive from pre-Hellenistic times. CalquesCalques denote literal translations of specific phrases from a host language to a recipient language. I thus exclude cases where entire texts were translated (such as the Egyptian version of the Hittite-Egyptian peace treaty, which also includes a rendering of the Hittite witness deities). Also a sentence such as jw=tw Hr rdj.t n=s tAy=s jsb.t jw=s Hr Hms = “her throne was brought to her and she sat down” in the Astarte Papyrus is an entire sentence translated from a Ugaritic original, tʕdb ks wy b, not an independently used translation of a phrase. Some examples of calques follow: 1) Northwest Semitic to Late Egyptian:An early example of a calque is nb.t kbn = bal.t gbl, “Lady of Byblos”. This author proposed the Ugaritic text KTU 1.12 as a source for the second part of the Tale of the Two Brothers (Papyrus BM 10183), with a possible calque in the expression aHAwtj nfr, “(most) perfect fighter” < Ugaritic aliy qrdm “the superior of fighters”.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Language Contact” by Thomas Schneider escholarship.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Coptic and Wolof language charts, Quora.com and the Proto-Semitic chart, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024