Home | Category: Death and Mummies

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TOMBS

inside a tomb

The wealthy were buried in elaborate tombs that were decorated with paintings from their lives and hieroglyphics that described their family, their achievements, offerings made at their funeral and a lists of feast days. Sometimes they featured battle scenes and scenes from everyday life like bread making, grain grinding and beer making.

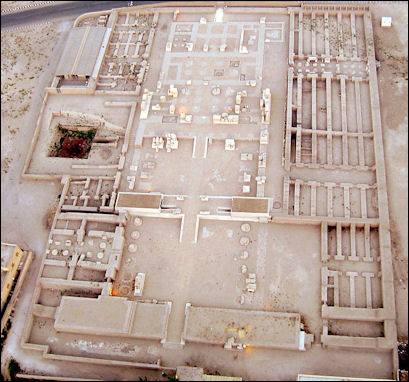

Large houses, temples and tombs all had similar plans with a main court, hall and private rooms. This was also true with Greek architecture. The Old Kingdom tombs were called mastabas. They were generally built of mud and stone above ground. Many were pyramid shaped. Later tombs were built underground. Tombs of teh rich were often filled with hieroglyphics. The text on the walls helped the deceased on the journey to the afterlife. These included magical incantations and lists of accomplishments and good deeds.

Tombs were sealed after the funeral but sometimes above them were chapels where mourners could come and pay their respects and priests could conduct rituals for the dead. Priests delivered meals to the dead by symbolically offering them to images of the deceased, who sort of magically inhaled the food. What was left over was often consumed by the priest or their families (the offerings were often the equivalent of their wages).

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Tomb in Ancient Egypt” by Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Tombs: The Culture of Life and Death” by Steven Snape (2011) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

“Early Burial Customs in Northern Egypt (BAR International)

by Joanna Debowska-Ludwin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs” by Philip J. Watson (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Tomb and Beyond: Burial Customs of the Egyptian Officials” by Naguib Kanawati (2001) Amazon.com;

“Living with the Dead: Ancestor Worship and Mortuary Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Nicola Harrington (2012) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes” by Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Tombs of Egypt: The Art of Thebes Revealed” by Zahi Hawass (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Lost Tombs of Thebes: Ancient Egypt: Life in Paradise” by Zahi Hawass and Sandro Vannini (2009) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor” by Nigel Strudwick (1999) Amazon.com;

Evolution of Mastabas to Rock-Tombs in Ancient Egypt

The mastaba tombs of the Old Kingdom are generally associated with the city of Memphis. They were built mostly by the aristocracy, who wished to rest near their monarch. Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, when the power of the king declined, the nobility of the nomes began to have their tombs built near their own homes, and at the same time we find a change in the form of the tombs. Instead of the mastaba, the rock-tomb was now preferred everywhere. This tomb had only been used before in a few cases on the low plateaus of Giza and Saqqara; it presented however the form most suitable for the higher and steeper rocky sides of the valleys of Upper Egypt. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: OLD KINGDOM TOMBS africame.factsanddetails.com

Nefertari tomb The details of the plan of these rock-tombs vary a good deal according to the riches of the family, and according to the ruling fashion; the chief characteristics are however common to all, even to tombs of different periods. Through a stately portico we reach the place of worship, which consisted of one or more spacious chambers, the walls of which were covered with reliefs or paintings of the customary kind. In a corner of one of these chambers there was a shaft (the so-called well), the opening of which was hidden, for it led to the mummy chamber. Sometimes several persons were buried in one tomb, which would then contain several wells. The statues of the deceased were placed, in accordance with later custom also, in a niche of the furthermost chamber.

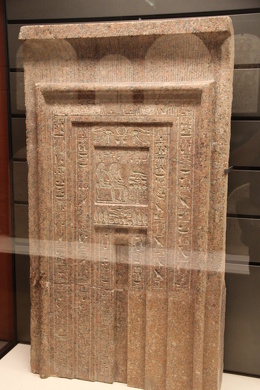

As with the mastabas so with the grotto-tombs, it was of course men of rank only who could afford them; they were far beyond the means of the middle class, who, after the close of the Old Kingdom began to build small tombs for themselves. The latter preferred to build at Abydos, the city of Osiris; and they were as a rule content with a shallow well to contain the coffin. Over this was built a little brick pyramid on a low pedestal, the whole being then plastered with Nile mud and whitened. In front of this pyramid there was sometimes, as in our illustration, a small porch, which served as a funeral chapel; in other cases the offerings and prayers were offered in the open air in front of the tomb, where was placed a stone slab, the funeral stela.

These stelae, which are so numerous in our museums, were originally identical with the false doors of the mastabas, and represented the entrance into the netherworld: they indicated the place to which the friends were to turn when they brought their offerings. The stelae in these little tombs of the poorer people were of course of very small dimensions — most were less than three feet high — and consequently their original signification was soon forgotten. Even at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom the door form disappeared completely, and the whole space of the stone was taken up with the representation of the deceased seated before a table of offerings receiving gifts from his relations and servants. Soon afterwards it became the custom to round off the stone at the top, and when, under the New Kingdom, pictures of a purely religious character took the place of the former representations, no one looking at the tomb stela could have guessed that it originated from the false door. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: VALLEY OF THE KINGS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, NEW KINGDOM TOMBS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Paintings

Wall paintings sometimes decorated the tombs of affluent ancient Egyptians. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science, Artists painted a variety of motifs, including portraits of the deceased, depictions of the gods, images of the deceased venerating the gods, and paintings of people mourning the deceased. Artwork in tombs sometimes also showed images of daily life in Egypt, as well as plants, animals and wildlife. They could even feature images of athletic events, such as wrestling and dancing. Hieroglyphs were sometimes drawn next to the wall paintings and provided information on who was buried in the tomb and what they did during their life. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 25, 2024]

Tombs of kings, queens and nobles were typically decorated with murals with images of deities and people known to the deceased. Sometimes there were images of the daily lives of ordinary people. Images in tombs are often accompanied by texts from the “Book of the Dead”, which sometimes explain what is going on in the picture. Some of the greatest existing works of Egyptian art are the tomb paintings in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, particularly the tomb of Neferteri.

Tombs typically contained: 1) images of the deceased performing tasks from everyday life or doing some great deed or achievement; 2) images of the deceased making offerings or sacrifices to Gods such as Anabus, Isis and Orissis; 3) images of cobras, gods with weapons or scorpions on their head intended to keep evil spirits from entering the tomb and protect the deceased; 4) images of deceased at the gates of the Nether World asking for permission to enter. To pass through each gate the deceased had to say the name of the gate and the god that guards it.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TOMB PAINTINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Sculptures

Nefertari tomb Statues of the deceased were sometimes placed in tombs next to the mummy. These were not intended for the public to see or as a memorial. They were a substitute for the person should something happen to the mummy, or they could be offered by the deceased as substitute if he was called on to do something unpleasant in the afterlife.

In some cases, these statues depicted deities. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science, For instance, in January 2024, archaeologists announced that they'd found a statue depicting Harpocrates, a childlike Greek god associated with silence, inside a tomb dating to around 2,000 years ago at Saqqara. They may have been placed to demonstrate the religious devotion of the deceased. Other times, statues showed the deceased and their families. For instance, in April 2023, archaeologists announced that they had found a 3,300-year-old tomb at Saqqara that belonged to a man named Panehsy. Inside, they found a statue of Panehsy and his family carved in relief. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 25, 2024]

The sculptures were often made of stone with the understanding that that meant they could last for eternity. If something happened to the mummy the pharaoh's “Ka”, or vital force, could move into the sculpture. Because they possessed ka, statues were regarded as powerful and even dangerous.

Some tombs contained "reserve heads" made from plaster casts of the mummified head which served the same purpose. The face on the sculpture had to recognizable, lest the ka get confused and inhabit the wrong statue.

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Contents

Tombs were often filled with belongings that the dead would take with them to the afterlife. The needs of the dead were similar to those of the living. Objects found in tombs included food, wine, jewelry, chariots, games, toys, cosmetics, cosmetic spoons, tubes to store eyeliner, jars of moisturizer, musical instruments, boats, pots held oil and fat, steaks and veal chops, sacrificed bulls, mummified birds, cats and baboons, gold funerary masks made to last for centuries, and living-room furniture to "make the afterlife more comfortable.” Widows used to bury a lock of their hair with their deceased husbands as a charm and perhaps symbolizing a vow to always be with her husband.

A tomb from 3150 B.C. of an Egyptian king, who may have been known as Scorpion I, contained a shrine, an ivory scepter, jars for oils, fats, bread, beer, cedar boxes for clothing, stone vessels, and ivory and bone objects, and three rooms full of jars of wine. The wine is believed to have been produced in Israel. Graves of the wealthy elite dated to 3500 B.C. contained flint figurines, beautiful pottery, and the earliest known funerary masks — expressive faces made with fired clay and featuring cut out eyes and molded ears.

Inside a tomb Ancient Egyptians were sometimes buried in sarcophagi decorated with illustrations. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science, Sometimes, these elaborate coffins have hieroglyphs that name the deceased and provide prayers for them. Just like modern nesting dolls, sarcophagi could include multiple sarcophagi housed within each other, with the mummified body at the center.Depending on the wealth of the individual, the sarcophagi could be made of expensive material. For instance, the sarcophagi of Tutankhamun were made with large amounts of gold. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 25, 2024]

The deceased were sometimes buried with mummy masks on their faces. The masks show an "idealized images of the deceased," according to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. They could be made out of plaster, cartonnage (a paper-mache material), linen and, on rare occasions, precious metals. In 2018, archaeologists working at the site of Saqqara discovered a silver mummy mask gilded with gold. It belonged to a priest who served Mut, a sky goddess.

Canopic jars held some of the organs of the deceased that were removed during the mummification process. Each organ, such as the lungs, liver, intestines and stomach, had their own jar according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The ancient Egyptians considered each organ to be protected by one of the four sons of the falcon-headed god Horus. The lungs were protected by Hapy (or Hapi), the liver by Imsety, the stomach by Duamutef and the intestines by Qebehsenuef, the museum notes. The jars, in turn, were sometimes placed in a canopic chest. A famous example is from the tomb of Tutankhamun, in which the four jars were placed in an alabaster chest.

Animal mummies were sometimes included in burials. These could be beloved pets who were buried with their owner for the afterlife, Lisa Sabbahy, an associate professor of Egyptology at The American University in Cairo, wrote in her book "All Things Ancient Egypt: An Encyclopedia of the Ancient Egyptian World" (Greenwood, 2019). Sometimes, remains of animals — such as cows, ducks and geese — were "prepared so that they were ready to be cooked" and then mummified, Sabbahy wrote. These remains would be for the tomb owner, and possibly their pets, to eat in the afterlife, she noted.

See Separate Article GRAVE GOODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

False Doors and Chambers in Ancient Egyptian Tombs

Many tombs had hidden doors and false doors (from which the dead could commune with the living and receive offerings) and real doors sealed with mud. The false doors often had hieroglyphic that identified the deceased. Some tombs had viewing holes, not so the people could look in the tomb, but so the pharaoh could look out and perhaps see the stars. [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

False door are associated mostly with the Old Kingdom A portion of each tomb was arranged that worshipers might look towards the west, the entrance into the hidden land; and in fact the decoration of this part of the tomb always represented that entrance in the form of a narrow door. In the most simple tombs this false door, on which the name of the deceased and prayers for the dead were written, was usually outside on the east wall, so that the worship went on in front of the tomb. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: False doors were intended to serve as portals that allowed the ka, or life force, of the deceased to move back and forth between the tomb and the afterlife. “Family members and priests would come to the tomb where the false door was standing and they would recite the name of the deceased and his or her achievements and leave offerings,” says Melanie Pitkin senior curator of antiquities at the University of Sydney’s Chau Chak Wing Museum and an affiliated researcher at the Fitzwilliam Museum at the University of Cambridge. “The ka of the deceased would then magically travel between the burial chamber and the netherworld. It would come and collect the food, drink, and offerings from the tomb to help sustain it in the afterlife.”[Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

As a rule a small chamber was cleared out at the south-cast corner, and on the further wall, looking towards the west, is found the false door with the inscriptions. These chambers represent are useful to archaeologists as the walls are often covered with inscriptions and pictures, from which we have obtained much knowledge about ancient Egypt. Whatever was dear to the deceased or valued by him is represented or related here — his titles, his estates, his workmen and officials, but all with reference specially to the tomb and to the funerary worship. The furniture of the funerary chamber is often rather minimal. Before the false door there was often a stone table of offerings; and close by, the high wooden stands with bowls for offerings of drink and oil. Some tomb chambers even had washbasin and toilets.

King Tut's Tomb

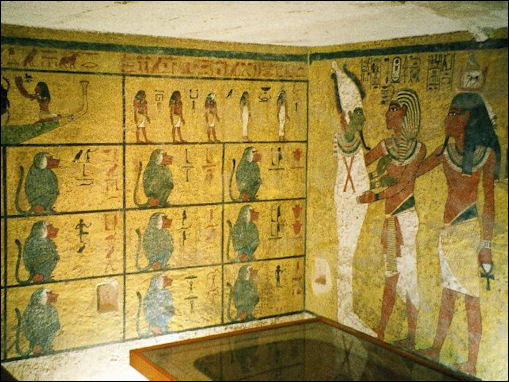

King Tutankhamen's Tomb (Valley of the Kings) is one of the most visited tombs in the Valley of the Kings and has a separate admission price. Its discovery in 1922 was one of the greatest archeological discoveries of all time. Tutankhamen was only a minor king — he didn't build a pyramid or any great temples or monuments and he died before he was 21 — but it just so happens that his tomb was one of the few in the Valley of the Kings with a treasure missed by looters.

King Tutankhamun Tomb is located 26 feet underground. It was constructed from the relatively small unfinished tomb of courtier after the king died at an early age. Objects for the afterlife were crammed in the tomb and the paintings were so hastily prepared that splashes of paint that cover some of the images was not cleaned up. Some of the burial objects appear to have belonged to others (their names were erased and replaced with King Tutankhamun’s name).

Tutankhamen was well prepared for his trip to the afterlife. His four-room tomb yielded gold treasures; gilt coffins with images of the king emblazoned on the them; a glittering throne with palace scenes; effigies of gods and goddesses; a chest inscribed battles scenes; and jeweled daggers, earrings, necklaces and other riches. The most famous object found in it was Tutankhamun’s blue and gold funerary mask, which has been pictured in many books and magazines. All of these things are in the Egyptian museum, except when they are on tour.

Some painting in the tomb depict Tutankhamun funeral procession. After the funeral procession, his successor, Aye, symbolically revives the dead. Nut, the sky goddess welcomes Tutankhamun to the realm of the gods, and Osiris, god of the afterlife, embraces him along with his “ka”, or spiritual double. Baboons on the far wall represent the start of his passage through 12 hours of the night.

See Separate Articles: TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: CONTENTS, ITEMS, TREASURES africame.factsanddetails.com ; DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT) africame.factsanddetails.com

Tomb of Nefertari

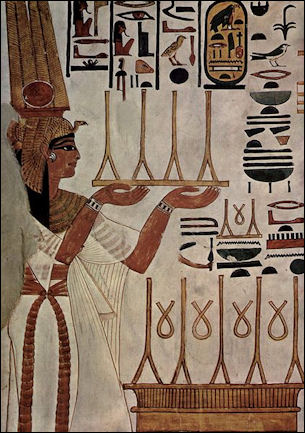

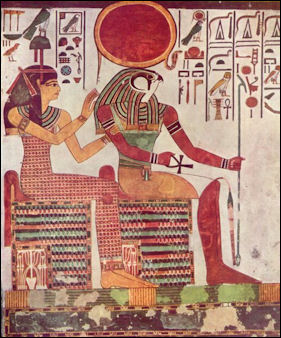

The Tomb of Nefertari (in the Valley of the Queens near Luxor) is the most beautiful tomb in the Valley of the Queens or the Valley of the Kings and one of the most extraordinary works of art in the world. Over 3,200 year old, it is in amazingly good condition for its age and features extraordinary wall murals, painted with vivid colors, great skill and a wonderful sensitivity for detail.

Regarded as a close representation of the "House of Eternity," the tomb of Queen Nefertari is composed of seven chambers—a hall, side chambers and rooms connected by a staircase—and features paintings made on engraved outlines of humans, deities, animals, magic objects, scenes of everyday life and symbols such as ibis heads, scarabs, papyrus, lotuses, vultures and cobras.

On being inside the tomb, Marlise Simons wrote in the New York Times,"The effect is rich like a house hung with jewelry, and it has an intensity that appeals strongly to modern eyes. But what makes these galleries just as moving is the fine detail of the images, their exquisitely carved relief and the gestures of endearment that give the figures life...There is are sweetness and intimacy that makes contact across the centuries seem somehow possible."

See Separate Article: TOMB OF NEFERTARI: CHAMBERS, PAINTINGS, MEANING OF THE ART africame.factsanddetails.com

Paying for and Maintaining Ancient Egyptian Tombs

Mortuary cults made up of priests and nobleman worshiped dead pharaohs, made periodic religious offerings and made sure the mummy was properly fed and dressed. "To ensure a continuous supply of food after death," scholar Daniel Boorstin wrote, "noblemen set aside land as an endowment for priests to feed them."

Decades, even centuries, after the pharaohs died priests still conducted daily rites around the tombs and pyramids. In these rites the priests sprinkled a statue of the pharaoh with perfume, painted on eye shadow and dressed it in new clothes while chanting prayers and mystical formulas. Occasionally a bull was sacrificed in the Sanctuary of the Knife; its throat was slashed, and the blood was captured in a huge bowl, and a foreleg was cut off and placed on the altar.

King Tut's tomb

Building a tomb in ancient Egyptian times was expensive. Some obtained help from the Pharaoh for the proper construction and equipment of their tombs. Thus, apparently at the same time as the building of his own pyramid, King Menkaure caused fifty of his royal workmen, under the direction of the high priest of Memphis, to erect a tomb for Debhen, an officer of his palace. He also had a double false door brought for him from the quarries of Tura, which was then carved for him by the royal architect. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

King Sahure presented his chief physician with a costly false door, ' which was carved under the eyes of the Pharaoh by his own artists and painted in lapis-lazuli color. The fate of this present was the same as that of many royal presents; the very modest tomb, which was all this learned man could afford to build for himself, looks all the poorer for this munificent royal gift. To others of his faithful servants the Pharaoh would send by the “treasurer of the god," with the “great transport ships of the court," a coffin together with its cover, which he had cut for them in the quarries of Tura.'' Under the Middle and the New Kingdom the good god not infrequently presented the statues which were placed in the tomb or in the temple for the funerary worship. On many of these wc can still read that they were "given as a reward ow the part of the king."

Use of Mud Brick in Ancient Egyptian Tombs

Virginia L. Emery of the University of Chicago wrote: “Even as it was used to house the living, so too was mud-brick employed to protect the dead. Paralleling its increased use in domestic settings, mud-brick was utilized to line the burial chambers of prehistoric tombs, as at Cemetery T at Naqada and the Decorated Tomb at Hierakonpolis (Tomb 100). Its use in funerary settings expanded during the 1st and 2nd Dynasties, being employed for chambers and vaults at Naqada, Tarkhan, el-Mahasna, Naga el-Deir, Abydos, Giza, and Saqqara. As time progressed, mud-brick was also used in the construction of tomb superstructures, as the mastabas at Naqada, Tarkhan, Abu Rawash, Giza, and particularly Saqqara attest. The mastabas from Saqqara offer the quintessential examples of palace façade style niching and buttressing; highly intricate examples of niching occurred during the 1st Dynasty, but became increasingly simplified through the 2nd and 3rd Dynasties and were replaced in the 4th Dynasty by straight-sided mastabas, a style that continued into the Middle Kingdom; classic examples of this style of mastaba dating to the 6th Dynasty occur at Balat/Ain Asil. [Source: Virginia L. Emery, University of Chicago, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Being related to royal burials, the Predynastic and Early Dynastic enclosures at Abydos and Hierakonpolis also display palace façade niching, as does a single example of a gateway within the town site of Hierakonpolis. The use of mud-brick in funerary monuments continued from the Old Kingdom into the Middle Kingdom, when not only mastabas but even the cores of royal pyramids were executed in mud-brick. The pyramids of the 12th Dynasty—of Senusret II at el-Lahun, of Senusret III and of Amenemhat III at Dahshur, of Amenemhat III at Hawara, and of Amenemhat IV and of Queen Neferusobek at Mazghuneh —and of the 13th Dynasty at Saqqara—of Userkara Khendjer and of an unknown king—continued the pyramid-building tradition of the Old Kingdom, but demonstrate an economy in the use of a mud-brick core cased with stone, which the all-stone Old Kingdom Pyramids lack. Mud-brick pyramids were built into the New Kingdom as private funerary monuments, especially in the Theban area and at Saqqara, though these miniature pyramids were no longer solid brickwork but had internal, vaulted chambers that served as the tombs’ chapels.

“Mud-brick continued to be used for the lining for burial chambers and for roof vaulting for the subterranean portions of tombs through the New Kingdom and into the Late Period, when the construction of tomb superstructures in mud-brick experienced a revival well-exemplified by still-standing monumental pylon entrances of the tombs of Mentuemhat (TT 34) and Padineith (TT 197) in the north Asasif area of the Theban necropolis. Ptolemaic, Roman, and even Coptic tombs continued to employ mud-brick.”

tomb of Seti I

Reuse of Tombs and Burial Equipment

One circumstance that forced the postponement of the building of the tomb was its great cost. Many men, whose rank obliged them to have their own tombs, had not the means to afford this luxury. There was a simple way out of this difficulty; without further trouble many people seized upon an ancient tomb that had perhaps belonged to an extinct family and was no longer cared for. If this were a grotto tomb, the walls were if necessary replastered and repainted; if it were a mastaba, it was rebuilt so far as was needful in order to remove the compromising inscriptions. '"' But this convenient expedient was considered sinful to a certain degree, and a really pious man preferred to build his tomb “on a pure place, on which no man had built his tomb; he also built his tomb of new material, and took no man's possession." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Peter Brand of the University of Memphis wrote: “Reuse of monuments in antiquity was not a strictly royal phenomenon. Private individuals frequently reused tombs and tomb furnishings—even those of ancestral relatives. The practice is occasionally attested in earlier periods, but most examples are from the New Kingdom and later. Many New Kingdom tombs in the Theban necropolis provide examples of reuse, ranging from the usurpation and alteration of tomb decoration in the Ramesside Period to intrusive burials in the Third Intermediate and Late Periods. The same was true in Memphis. [Source: Peter Brand, University of Memphis, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Funerary equipment could also be usurped or recycled after it had been adapted for the new owners. For example, a Nineteenth Dynasty coffin was replastered and repainted in the Twenty-first Dynasty for a man named Mentuhotep. Traces of the original decoration are visible where the newer plaster chipped off. Sarcophagi, too, could be re-inscribed, as was the anthropoid sarcophagus prepared for general Paramessu before he became Ramesses I, the sarcophagus later being adapted for prince Ramesses, the son of Ramesses II. Unlike the royal practice of employing masonry taken from ruined or obsolete monuments, the private recycling of funerary equipment was often an illegitimate or criminal act, the goods themselves frequently being obtained by theft. Yet tombs and funerary equipment were often plundered within a few generations of the burial of the original owner(s). The later Twentieth Dynasty saw the brazen and systematic plundering of the Theban necropolis, including royal and private tombs and royal memorial temples. Plundered funerary goods were reused “as is” or reprocessed for valuable raw materials.

Tomb Texts from Ancient Egypt

Tombs were often filled with hieroglyphics. The text on the walls helped the deceased on the journey to the afterlife. These included magical incantations and lists of accomplishments and good deeds.

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “Practically everything that we know about Egyptian kings derives from their monuments. The Pyramid Texts, which were spells concerning the king's afterlife, began to be inscribed inside Egyptian pyramids from the reign of King Unas, about 2350 B.C. The temples for the king's posthumous cult were decorated with reliefs and contained many statues, all of which give us information about the role of the king in Egyptian society. Scenes that show real events are rare. We must not forget that the purpose of these reliefs was to show an ideal state of affairs, which the king wished to last forever, not the contemporary reality. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

"Scenes of Asiatic Commerce in Theban Tombs (Rek-mi-Re)" from the Tombs of the Noblemen (15th-13th Century B.C.) reads: Coming in peace by the princes of Retenu and all northern countries of the ends of Asia, bowing down in humility, with their tribute upon their backs, seeking that there be given them the breath of life and desiring to be subject to his majesty, for they have seen his very great victories and the terror of him has mastered their hearts. Now it is the Hereditary Prince, Count, Father and Beloved of the God, great trusted man of the Lord of the Two Lands, Mayor and Vizier, Rekh-mi-Re (reign of Thothmosis III), who receives the tribute of all foreign countries...Presenting the children of the princes of the southern countries, along with the children of the princes of the northern countries, who were brought as the best of the booty of his majesty, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt: Men-kheper-Re (Thothmosis III), given life, from all foreign countries, to fill the workshop and to be serfs of the divine offerings of his father Amon, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, according as there have been given to him all foreign countries together in his grasp, with their princes prostrated under his sandals .[Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” (ANET), Princeton, 1969, pp. 248 web.archive.org]

Merenptah's Mortuary Temple

Main Tomb Sites at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The Royal Tomb, one of the foundations listed on the Boundary Stelae, was cut into the limestone bedrock deep in the Royal Wadi in the eastern cliffs, recalling the Valley of the Kings in Luxor. Although unfinished, the tomb was used for the buri als of Akhenaten, princess Meketaten, probably Queen Tiy, and another individual, perhaps Nefertiti. At the end of the Amarna Period the contents of the tomb were partly relocated to Thebes. The tomb was badly looted shortly after its discovery in the late nineteenth century and has suffered subsequently from vandalism and flooding. The walls nonetheless retain important scenes, including those alluding to the death of princess Meketaten, perhaps in childbirth. The Royal Wadi also conta ins three additional unfinished tombs and another chamber that is either a store for embalming materials or a further tomb.[Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

The North Tombs are a set of elite tombs cut into the cliffs of the high desert towards the northern end of the Amarna bay. There are six principal tombs, numbered 1-6, which belonged to high officials in Akhenaten’s court. Although none was fully completed, these preserve decoration that is notable for representing the city’s monuments, the prominence given to the king and royal family, and the presence of copies of the Hymns to the Aten . There are also several other undecorated tombs. The tombs were reoccupied by a Coptic community in around the sixth to seventh centuries CE and the tomb of Panehesy (no. 6) converted into a church at this time.

“Adjacent to the North Tombs are a number of non-elite burial grounds. The largest, which probably includes several thousand interments, occupies a broad wadi between North Tombs 2 and 3. The graves here take the form of simple pits cut into the sand, containing one or more individuals wrapped usually in textile and mats. There is also a smaller cemetery at the base of t he cliffs adjacent to the tomb of Panehesy (no. 6) and another in the low desert some 700 meters to the west of this, both as yet unexcavated.

“South Tombs and South Tombs Cemetery, a second group of rock-cut tombs belonging to the city’s elite, is situated at the cliff-face southeast of the Main City. There are 19 numbered tombs (nos. 7-25) and several other unnumbered chambers. The tombs are in a less finished state and are smaller tha n the North Tombs. Large quantities of pottery dating to Dynasties 25 and 30 litter the ground nearby, suggesting the tombs were reused in the Late Period.

“The rock-cut tombs are again only the elite component of a much larger cemetery that occupies a 400 meters long wadi between Tombs 24 and 25. Fieldwork here from 2005 to 2013 revealed a densely packed cemetery containing the graves of several thousand people, those of adults, children, and infants intermingled. The deceased were usually wrapped in textile and a mat of palm midrib or tamarisk and placed singly in a pit in the sand. Less often, they were buried in coff ins made of wood, pottery, or mud. The decorated coffins include examples with traditional funerary deities, and in a new style in which human offering bearers replace the latter. Most graves seem to have been marked by a simple stone cairn, and in some ca ses a small pyramidion or pointed stela showing a figure of the deceased . Fragments of pottery vessels that presumably often contained or symbolized offerings of food and drink were common. Other grave goods were rare, but included such items as mirrors, kohl tubes, stone and faience vessels, tweezers, and jewelry such as scarabs and amuletic beads. The study of the human remains showed an inverse mortality curve, ages at death highest between 7 and 35 years, with the peak between 15 and 24 years.”

Ground plan of the Tomb of Seti I

Rock-Cut Tombs of Amarna

Janne Arp-Neumann wrote; The monumental rock-cut tombs of Tell el-Amarna were constructed for members of the elite and for Pharaoh Akhenaten with his family. These monuments are reckoned to be a main source for studying the religion of the so-called “Amarna Period”, their walls bearing for example the widely known “hymns to the Aten”. All tombs are located on the east bank of the Nile, the private tombs in the limestone cliffs and foothills surrounding the city of Akhetaten to the east. Their outline encompasses one to three rooms furnished with columns, statues and reliefs. The burial was foreseen underneath those rooms, following a sloping passage or a shaft. The royal tombs were constructed in remote wadis behind the cliffs, their main axes being sloping passages themselves. The rooms for the burial of the royal family were decorated with relief, too, but special architectural features are limited to pillars. Due to the comparatively short period of occupation of the city, most of the tomb structures have not been completed and not been used for burial. [Source: Janne Arp-Neumann, Universität Göttingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

According to Aidan Dodson, up to seven sepulchral units might have been planned to be included in this one tomb. It is known that WV 22, the tomb of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten’s immediate predecessor, also provided for the burial of at least the queen and possibly one princess. The entrance of TA 26 is a spacious stairway of 20 steps with a central slide leading westward toward the entrance doorway. A descending corridor is followed by another, steeper stairway C), with 16-18 roughly hewn steps and a central slide. Along the axis are a shaft room and a large (20 square meters), square, pillared hall, with two of the original four pillars remaining on the south side and, on the north side, a plinth on the floor for the sarcophagus. The plinth is located a bit off-axis but is oriented in the same direction. An opening to an unfinished room F) was hewn into the western end of the pillared hall’s north wall.

Two suites of rooms branch off the northern side of the main axis, firstly from the corridor 1-6) and secondly from the stairway. The succession of rooms 1-6 changes directions two times (first east, then west), with room 3 being a curved corridor. Room D is the first in the sequence of rooms on the main axis to have been decorated. The contents of this decoration, as far as it is still recognizable, are stylized representations of floral bouquets and depictions of the royal family worshipping the Aten. In room E/J, the pillars and the short walls next to the doorways also bear traces of the royal family offering to the Aten and of stylized floral bouquets. The southern wall (B) of room E/J has remains of a mourning scene: A female figure with a sash stands in an open canopied shrine decorated with a frieze of uraei, while the royal couple stands in front of the shrine with offerings. The individual mourned is assumed to be the dowager Queen Tiy, while the mourning queen is identified as Nefertiti by her characteristic crown. It is noteworthy that two female figures carrying funerary furnishings are by their attire interpreted as princesses. The opposite, northern wall of room E shows traces of another mourning scene, but neither the person mourned, nor the mourners, are identifiable. Martin proposes the individual mourned to have been Akhenaten, since this scene is closest to the sarcophagus, which he supposes to have been the king’s. The relief decoration of the sarcophagus, as far as it can be judged from the fragments, is singular in its depiction of Nefertiti in place of the protective deities at the corners, and of the sun disk with its descending rays on all four sides and at the corners above the figure of the queen, and of cartouches in the spaces underneath the rays and between the figures. The lid was reconstructed by Maarten Raven to bear one central sun disk at the head with rays descending to approximately three quarters of its expanse, the quarter at the foot-end covered with cartouches.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Amarna: Private and Royal Tombs” by Janne Arp-Neumann escholarship.org

Tomb of Set I

Ancient Egyptian Priest Tomb

In 1996, the undisturbed and unlooted 2,500-year-old tomb of a high-ranking priest named Iuffa was discovered by archaeologists for the Czech Republic's Charles University in Abusir at a a site about five mile south of the Pyramids of Giza. The coffin was situated at the bottom an 84-foot-deep shaft. It was surrounded by an inner sarcophagus and outer sarcophagus that was placed on a pile of sand in the shaft and had been lowered by removing the sand to other shafts. After the sarcophagus was lowered a vaulted stone chamber was built around it. The door was sealed and the sand was deposited in the shaft. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, November 1998]

So difficult was the project to excavate the tomb, archaeologists spent three years extracting the sarcophagus from the shaft and open the coffin. Beams and jacks and laborers pulling chains were used to pull the lid off the sarcophagus. The project wasn't completed until 1998.

Filling most of the burial chamber, the box-shaped white limestone outer sarcophagus was 16 feet long and 11 feet wide. The lid alone weighed 24 tones. Along the sides of chamber were tomb furnishings four canopic jars with internal organs. The jars looked like coffins and bore likenesses of the priest’s head.

Inside the outer sarcophagus was a layer of mud bricks and mummy-shaped plaster. The sarcophagus was made from gray basalt and covered with fine carvings and hieroglyphics. Inside was a decayed wooden coffin that turned to powder with a touch. Inside it was mummy covered with a shroud filled with glazed ceramic beads organized in patterns depicting gods of the afterlife such as Nut and the sons of Horus. Moisture had penetrated the coffin so the mummy crumbled to powder with a touch. The mummy's fingers were sheathed in gold.

Hieroglyphic identified Ifuaa as a lector priest and an administrator of palaces. He was a member of the elite class and is believed to have assisted gods and kings and read spells and performed rites. He lived during a period of Egyptian cultural revival and died during the Persian occupation.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024