Home | Category: Religion and Gods / Art and Architecture

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN RELIGIOUS SYMBOLS

Eye of Horus

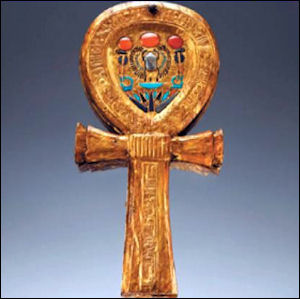

The Ankh is the symbol of life. Worn only by pharaohs and gods, it indicates that the wearer has the power to give and take away life. Obelisks, cobras and discs are all symbols of the sun. The cobra and vulture symbolize the Upper and Lower kingdoms of Egypt.

The prevailing eyes (the holy symbol of the ancient Egyptian religion) represent the eyes of Horus and symbolize the sun and the moon and represent good health. According to legend, Horus lost the eye in a fight with Seth and had his eye restored by the goddess Hathor. It is a common motif in Egyptian art and often appears on amulets and tomb paintings.

Hieroglyphic texts are filled with titles and names. For example a walking duck followed by a circle with a bull’s eye means "son of [the sun god] Ra." This combination of symbols often preceded the name a pharaoh. Various combinations of symbols can represent objects, pronouns, possessive pronouns and question words. Some hieroglyphic letters serve as prepositions: The owl can represent "of" or "with"; the water line can represent "to" or "for." Other hieroglyphic letters can represent personal pronouns. A horned snake can be "he," "him," "his" and "it" and a basket with a handle can represent "you."

Cobras were an important symbol of the ancient Egyptians. A cobra was on the headdress of the pharaoh and appears often in art and religious imagery. Egyptian cobras were represented in Egyptian mythology by the cobra-headed goddess Meretseger. A stylised Egyptian cobra — in the form of the “uraeus” representing the goddess Wadjet — was the symbol of sovereignty for the Pharaohs.

See Egyptian cobras under VENOMOUS SNAKES IN THE MIDDLE EAST africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Symbols: 50 New Discoveries” by Jonathan Meader and Barbara Demeter (2016) Amazon.com;

“Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art” by Richard H. Wilkinson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Manfred Lurker (1984) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt” by Robert Thomas Rundle Clark Amazon.com;

“Esoterism and Symbol” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (1985) Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James (2025) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion” by Donald B. Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Symbols of the Egyptian Pharaoh

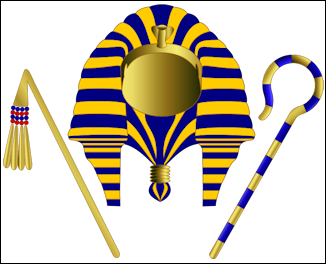

crook and flail, Pharaoh symbols As a sign of their authority a pharaoh wore a false beard, a lion’s main and a “nemes” or headcloth with a sacred cobra. When offering were made he waived the royal “sekhem” (scepter) over them. The beard on the statue of a pharaoh identifies him as being one with Osiris, god of the dead. The cobra and vulture on his forehead symbolize the Upper and Lower kingdoms of Egypt. The crook and flail held the Pharaoh’s hands symbolized the king's power and also linked him with Osiris (statues of Osiris also have a crook and flail). The pharaoh's power was symbolized by a flabellum (fan) held in one hand.

The symbols of authority of the ancient Egyptian king included a crook and a flail. The crook was a short stick curved at the top, much like a shepherd’s crook. The flail was a long handle with three strings of beads. When the king sat on his throne wearing all of his symbols of office—the crowns, scepters, and other ceremonial items—it was believed the spirit of the great god Horus spoke through him. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Crowns and headdresses were mostly made of organic materials and have not survived but we know what they looked like from many pictures and statues. The best known crown is from Tutankhamun’s golden death mask. The White Crown represented Upper Egypt, and the Red Crown, Lower Egypt (around the Nile Delta). Sometimes these crowns were worn together and called the Double Crown, and were the symbol of a united Egypt. There was also a third crown worn by the kings of the New Kingdom, called the Blue Crown or war helmet. This was called the Nemes crown and was made of striped cloth. It was tied around the head, covered the neck and shoulders, and was knotted into a tail at the back. The brow was decorated with the “uraeus,” a cobra and vulture.

See Separate Article: SYMBOLS OF THE PHARAOHs africame.factsanddetails.com

Mace

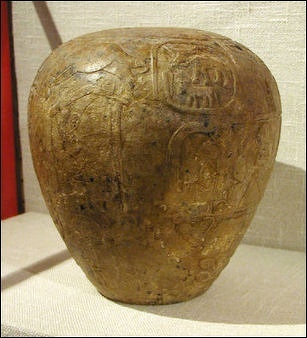

Maces, club-like weapons, have been found in ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period onward,. They played both functional and ceremonial roles, but are associated most with the latter. By the First Dynasty they had become closely linked with the power of the king, arguably so much it became of a symbols of this power. The archetypal image of pharaoh wielding a mace endured until the Roman Period. [Source: Alice Stevenson, University of Cambridge, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Alice Stevenson of University of Cambridge wrote: “A mace is a club-like weapon with a heavy head pierced through for the insertion of a handle. The mace is often considered to be the characteristic weapon of Predynastic Egypt, as Predynastic maceheads (which usually survived their handles) are comparatively numerous. Nevertheless, even in the Predynastic Period, the mace’s additional function as a ceremonial object—a role ascribed to it throughout Egyptian history— seems likely.”

The “image of the smiting pharaoh held great iconographical significance throughout Pharaonic history as is evidenced by numerous temple inscriptions and reliefs, although it was most prevalent from the New Kingdom through the Roman Period. In representative scenes the king smites an individual or group of enemies...most commonly with a mace. As one of the most frequently depicted themes in royal iconography, it has been referred to as the “Smiting of the Enemy” topos and has been cited as an important motif of the Pharaonic “Great Tradition”. Notable examples of (intact) maces include two gessoed and gilded wooden maces found between the outermost and second shrines in Tutankhamun’s burial chamber.

Two types of mace appear as hieroglyphic signs—the mnw-mace and the HD-mace —and there is a clear distinction between them in the terminology. A third sign depicts the HD-mace with straps. The mnw sign features a representation of a disc-shaped macehead and is used in the writing of the word “mnw-mace” on coffins, where it is frequently contrasted with writings of the word “HD-mace,” which feature a depiction of a round or piriform macehead. The mnw-mace hieroglyph is attested in writing the word “mace” only from the Middle Kingdom to the Late Period (712–332 B.C.); however, the sign (and accordingly the word) must necessarily be older, as it is already used as a phonetic component in the Pyramid Texts. The regular word for “mace” in the Pyramid Texts is HD.”

Predynastic Period Maces

Narmer macehead

Alice Stevenson of University of Cambridge wrote: “Polished stone maceheads are attested in Egyptian burials from as early as the Predynastic Period. Disc-shaped maceheads are found in some Naqada I graves and are known from the Khartoum Neolithic. Pear-shaped, or “piriform,” maceheads were favored in Naqada II, although the earliest examples are from the Neolithic 5th-millenium settlement site of Merimde Beni-Salame. Very infrequently ring- shaped and double-ended examples are encountered, but it is the pear-shaped form that became prevalent in dynastic Egypt. Maceheads were made in a wide variety of stones including diorite, alabaster, dolomite, and limestone, the latter material becoming the preferred medium in the late Predynastic. [Source: Alice Stevenson, University of Cambridge, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The handles to which maceheads were hafted were probably organic and rarely survive, or may not have been commonly included in graves. The exceptions include a handle of wood from a grave at el-Mahasna; the handles of two intact discoid maces from grave B86 at Abadiya—a 330-mm handle of oryx horn and an ivory example of similar length; an especially elaborate handle of sheet- gold casting embossed with an animal frieze, from grave 1 at Sayala, in Nubia; and a more recently excavated example painted with red and black stripes, from grave 24 at Adaima.

“In an initial study of 100 Predynastic graves with maceheads, Cialowicz noted that the maceheads were more common in the graves of males, but were not rare in the graves of females. Given the unreliability of sex attribution in preliminary excavation reports, however , these conclusions are, at present, tentative. The presence of maceheads in graves is often assumed to be an indication of authority or status, but this assumption is based on later historical parallels: whether the value and meaning of maceheads remained unchanged from much earlier Predynastic conceptions remains open to debate.”

Ceremonial Maces

Alice Stevenson of University of Cambridge wrote: “Not all maces were employed in a functional capacity—that is, as actual weapons. Their symbolic role is certainly suggested in the Predynastic Period by the presence of model maces, such as that found at el-Amra. Moreover, maceheads found in the “Main Deposit” at Hierakonpolis— particularly four large pear-shaped limestone examples, together with a smaller ivory one—appear to demonstrate a linkage with the emerging ideology of kingship. They are carved with elaborate raised reliefs arranged in registers datable to approximately the early First Dynasty, and their exceptional size and artistic accomplishment clearly set them apart as “ceremonial” objects. [Source: Alice Stevenson, University of Cambridge, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“A brief description of the exceptional maceheads from the Main Deposit is in order. The “Scorpion macehead” measures about 250 mm high. The surviving portion (less than half) depicts an individual, often identified as King Scorpion on the basis of the scorpion carved in front of the face, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, a tunic, and a bull’s tail, and holding a hoe. The “Narmer macehead” portrays Narmer seated in a kiosk, wearing the red crown and a close-fitting cloak, with attendant officials and standard- bearers. The scene has been variously interpreted as a marriage ceremony, a year-name, and as Narmer’s participation in a Sed-festival .

“The relief on the “King’s macehead” is badly damaged, but the surviving portion shows the king attired in the red crown and a cloak, seated in a kiosk with a falcon facing him. The preserved sections of the “Bearer macehead” show only the fragmented images of several individuals, some holding vessels and/or animal skins. The small ivory macehead depicts captives tied at the neck, their arms bound behind their backs.

“Some scholars have preferred not to interpret these scenes literally—that is, as representations of actual events—but consider them part of a wider repertoire of ceremonial objects, including palettes and knives, that were appropriated to play a role in the secluded world of elite culture . Rather than abstracting the scenes from the objects upon which they are depicted, these scholars propose a more holistic interpretive approach that reasserts the images as an integral part of the (tangible) artifacts themselves, linking the artifacts to their Predynastic development and thus connecting decorative form with object function.

“In addition to the Late Predynastic/Early Dynastic ceremonial maceheads in the Hierakonpolis “Main Deposit,” several plain “functional” maceheads of pink limestone and of standard size, as well as a number of decorated mace handles, were found at the site. The phenomenon of collecting both weapons and symbols together in a deposit is also attested in the eastern Nile Delta at Tell Ibrahim Awad, where several plain calcite maceheads were discovered along with small votive objects of various kinds, including faience tiles and faience baboons, all presumably of Early Dynastic date upon comparison with similar examples found in the Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis. It is significant that both deposits also contained Old Kingdom material datable up to the Fifth Dynasty, suggesting that a process of decommissioning of symbolically potent Early Dynastic objects, including maces, took place throughout Egypt toward the end of the Old Kingdom.

“The Hierakonpolis Main Deposit also provides further evidence that the mace had become an important component of the regalia of kingship by the Early Dynastic Period, as a potent symbol of royal power. Such symbolism is manifested in the form of another class of ceremonial object—the palette—with which ceremonial maces share close stylistic similarities. Representative is the Narmer palette, upon which the king is shown brandishing a mace above a group of captives.”

Scarabs

scarab The black scarab beetle was revered as a symbol of the sun god and rebirth. They were believed to be the source of the power that makes the sun move across the sky and were connected with Kheperi, the god of the rising sun an resurrection.

Scarabs were buried with mummies. Small statuettes of scarabs were carved from valuable stones. The Egyptians worshiped scarabs as symbols of immortality because they entered the ground and later emerged again as if resurrected.

Scarab beetles are dung beetles. They feed on recycling plant matter and feces. Some have brilliant iridescent colors. African scarab beetles roll animal dung into balls, which are buried and eaten by beetle larvae. Their association with power and energy is believed to be tied to their energetic rolling of dung. Their connection with rebirth is tied to fact the bugs lay their eggs in dung, and are thus reborn from waste.

Dung beetles work by themselves or in pairs to build perfect balls of dung larger than themselves and then stand on their front legs and push and roll the balls of dung backwards with their back legs and then bury it. The dung beetle selects the least fibrous bits of dung for its ball. They bury tons of material a year, fertilizing the soil by entrapping nitrogen underground where I can be utilized by plants.

Dung beetles are thought to have got their start by feeding on dinosaur dung before moving on to mammals. Today they occupy an important environmental niche, moving dung underground, where it can be used as fertilizer for plants and can sprout seeds rather than staying aboveground where it can attract flies, diseases, beastly smells or be washed away and fowl waterways.

Some species cut out pieces of dung and roll it away for private consumption. Others dig under a deposit and draw it into their tunnels. The tunneling species have evolved horns which the use to protect their tunnels from other males.

Dung beetles bury the dung to keep it away from competitors and provide a safe place for their offspring to grow up. Females lay their eggs in the dung and the larvae fed on the dung until they develop into beetles.

The beetles do their work mostly at night When a ball is complete, a beetles moves it as quickly as it can to a shelter so the ball is not stolen by another beetle. Studies have shown that dung beetles are able to strike out in a direct line to their shelter when the moon is full but have difficulty finding the way on moonless nights. Further studies shows the beetles oriented themselves not to the moon itself but used moonlight to navigate their way.

Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: “The Latin scarabaeus (“beetle”), from Greek karabos (“beetle”; “crayfish”), is an artistic representation of the indigenous Egyptian dung beetle (species Scarabaeus sacer), an insect that rolls balls of dung in which to lay its eggs. The ancient Egyptians linked this unique reproductive behavior to mythological cycles of solar death and rebirth. The scarab was used by the ancient Egyptians as a symbol of the rising sun being pushed across the sky (just as the beetle pushes balls of dung across the sand), exemplifying the notion that the sun god can create his own means of rebirth. Such representations can be seen in the scarab’s multiple depictions in the Amduat, a New Kingdom composition describing the sun’s nighttime journey through the netherworld. This notion of masculine self- resurrection is clarified in the scarab’s function as a hieroglyphic sign, an example of which is featured in the verb xpr, “to come into being,” and its derivatives. The noun “scarab,” xprr (literally “that which comes into being”), could refer to either the scarab beetle or to the amulet. [Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Types of Scarabs

Kushite victory commemoration scarab

Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: There are a number of different kinds of scarabs, including heart scarabs, commemorative scarabs, and scarab amulets, indicating their different functions within varying social contexts—from apotropaic to amuletic, socioeconomic, and propagandistic. The blank oval underside of the scarab amulet was an excellent location for the inscription of personal names, kings’ names, apotropaic sayings, or geometric or figural designs. [Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Heart Scarab: The best known is the heart scarab, the earliest examples dating to the 17th Dynasty. The heart scarab is a large amulet, ideally made of green stone (nmHf), inscribed with Chapter 30B from the Book of the Dead . It was placed on the mummy, often within a pectoral, or in the vicinity of the mummy, in order to control the consciousness and memory of the deceased in the halls of justice, lest the heart speak against its owner. The so-called winged scarab, similar to the heart scarab in form and size but lacking an inscription on the underside, was common in the Late Period (712–332 B.C.); this faience scarab allowed identification of the deceased with the reborn sun god. It was placed on the heart of the mummy with detached outspread wings on either side, all usually part of a faience beaded network that covered the chest and legs of the mummy.

“The Commemorative Scarab: Another well-known scarab type is the so- called commemorative scarab, the underside of which is inscribed with an announcement from the royal family. These large scarabs were first produced in the 18th Dynasty in the reign of Thutmose IV, reached a height of production under Amenhotep III, and continued to be produced, but to a lesser extent, under Akhenaten. The underside of the commemorative scarab includes about ten lines of text, the most famous of which relate the building of a lake for Queen Tiye, the hunting prowess of Amenhotep III, and this same ruler’s marriage to Mitannian princess Gilukhepa. The commemorative scarab played a number of social roles, in particular that of spreading knowledge of royal achievements, status, and wealth throughout elite society in Egypt and beyond, creating a kind of mobile and personalized propaganda network

“Scarab Amulet: The most common scarab type is the scarab amulet, so ubiquitous that it is usually referenced in the Egyptological and archaeological literature simply as “scarab”. The beetle form was ideal for use as an amulet. Most scarab amulets are quite small, measuring between 10 mm and 50 mm in length. They are ovoid in shape, the back of the amulet depicting the head and folded wings of the insect and the sides depicting the legs. The scarab amulet is usually pierced longitudinally, so that the owner could wear the object as a ring, necklace, or bracelet. The blank oval underside of the scarab amulet was an excellent location for the inscription of personal names, kings’ names, apotropaic sayings, geometric designs, or figural representations. The scarab amulet could be carved from a variety of stones, including costly amethyst, jasper, carnelian, and lapis lazuli, or from less expensive stones, such as steatite, which was usually glazed. A great many scarab amulets were molded from faience, especially in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.). The earliest scarab amulets are dated stylistically to the 6th Dynasty; most early examples are uninscribed. The first scarab seals, bearing the name and title of the owner, developed in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). The scarab’s use continued in ancient Egypt until the Ptolemaic Period , although production after the reign of Ramses III was limited. The so-called “scaraboid” also belongs to this class of object and describes any amulet carved in the standard ovoid shape but depicting an animal, such as a goose, cat, or frog, rather than a beetle.”

Scarab Amulet Decoration and Meaning

Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: “It is quite common to organize scarabs by the type of decoration found on the scarab base. The first type of scarab base decoration includes examples ranging in date from the Middle Kingdom through the Late Period, depicting apotropaic and divine iconography, including images of gods and so-called good- luck sayings. This group also includes scarabs from the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period that are particularly associated with the god Amen and the many cryptographic writings of this god’s name. [Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The second type of scarab base includes rulers’ names, epithets, and images, and these examples also date from the Middle Kingdom through the Late Period. The scarab represented the rebirth of the sun god and was therefore intimately associated with cycles of masculine royal renewal and, by extension, Egyptian political power systems. Because of the association of the king and the sun god, scarabs were often inscribed with the names and/or depictions of the king (either currently reigning or deceased). In many ways the scarab was meant to be a gendered object. The word xpr, when used as a noun, is masculine, and most iconography on the underside of scarabs revolves around the masculine political world—of kings and courtiers. This is not to say that a scarab amulet could not depict or be owned by a woman, just that it was more representative of masculine spheres of power and kingship.

scarab with wings

“A third category of scarab base decoration features non-royal personal names and titles, suggesting the scarab’s use as the owner’s personal seal, a type that reached its height in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). Most of these non-royal names and titles belong to holders of elite offices or priesthoods. A fourth decorative group depicts motifs of northwest Asian origin, in addition to foreign adaptations of Egyptian iconography. Many of these scarabs date from the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (the period of Hyksos domination). Others date to the New Kingdom, when Egypt’s empire reached its apex.

“A fifth scarab amulet group features geometric and stylized patterns, many of them dating to the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period. Most common within this group are abstract geometric, scroll, spiral, woven, floral, and even humanoid patterns. It should also be mentioned that many scarab amulet undersides are uninscribed, and many such examples are made of semi-precious stones.”

Uses of Scarab Amulets

Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: “The small size and compact shape of the scarab amulet facilitated mobility and distribution, making the object amenable to various public and private political agendas. In the Middle Kingdom, scarabs were often utilized as seals by non-royal bureaucrats, and many personal names and titles are found on scarabs. Scarabs were manipulated as political tools by the Hyksos kings and their officials during the Second Intermediate Period, when inscribed examples were ostensibly distributed to elites and vassals. During the New Kingdom, scarab amulets and seals were spread throughout the increasingly connected Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds, and particularly the Levant; as such, the occurrence of kings’ names and figures became especially common. The New Kingdom also saw a blossoming of personal piety in scarab amulet design, when seal iconography increasingly turned towards divine figures, aphorisms, and cryptography. [Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

King Tut scarab

“The wide range of scarab decorative genres complicates the issue of scarab meaning and, by extension, function. Scarab amulets fulfilled multiple uses: as administrative tools, as markers of social status, as distributed propaganda messages, or as apotropaic talismans. It is therefore very difficult to place these objects into specific religious, political, or socio-economic categories. Discussion of a given scarab’s decorative genre and function is partly dependent on its production, distribution, and reception—all processes that are difficult to discern in the preserved ancient record, and especially that of unprovenanced scarabs from private collections.

“The small size of the scarab base required the creation and utilization of abbreviated, abstracted, and “loaded” iconography that could be multi-functional and multi- interpretational for the scarab owner. Such iconography provided layers of complexity, because conceptual signs and symbols have multiple grammatical and semiotic meanings, resulting in the overlap of genres and thus scholarly confusion about scarab function. Ultimately, the best explanation of scarab function is that the scarab amulet held a number of meanings and functions simultaneously, depending on the manu- facturer’s intent, the owner’s understanding of the piece, and the occasions of its use. Some of these meanings are amenable to protection and personal piety, while others point to a socio-political use. The scarab amulet’s symbolism was intended to be inclusive and broad, rather than confined to one particular meaning in a given circumstance.”

Scarab Amulet Dating

Scarabs are extremely difficult to date; very few are found in archaeological context and most are unprovenanced in private and museum collections. Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: “Scarab base-decoration is commonly used as a dating tool; nonetheless, it is notoriously difficult to use a scarab found in context to date an archaeological site. Many scarabs are inscribed with the names of rulers already dead at the time of production; others are heirlooms, found entirely out of their production context. Many scarab and seal specialists rightly call for contextual study that incorporates historical and archaeological data, but this is impossible with art-market pieces, which make up the bulk of scarab collections aroundthe world. Modern forgeries complicate the issue of dating even more. In the end, many scarab specialists base their dating on stylistic comparison to other scarabs, only some of which are found in archaeological contexts. [Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Even scarab inscriptions with royal names cannot necessarily be dated to the reigns of those rulers, because such names are often inscribed long after a ruler’s death— particularly those of the 4th-Dynasty king Sneferu, the 18th-Dynasty Thutmose III, and the 19th-Dynasty Ramesses Scarab amulets inscribed with royal names contribute less to scarab typological development than one would hope, providing only the terminus post quem date. Nonetheless, many scarab publications have used the royal names inscribed on scarabs as dating criteria, dating other, non-royal, scarabs based on stylistic comparison with these named scarabs. Other scarab experts have reacted against this circular use of unreliably dated comperanda by not providing dates at all . Egyptologists and archaeologists have also attempted dating typologies based on the style of scarab backs, heads, and legs, so as to avoid or to check the suggested date of the decoration . Typological dating of scarab forms is most useful when dealing with larger scarab groups statistically, but it is not very helpful for dating individual scarabs without common archaeological provenance. Recent scarab studies use all available criteria—inscription, form, material, size, and archaeological context, for example—to provide wide date-ranges rather than exact reigns. Very broad date-ranges are now the norm in scarab publications

Akh

Ankh mirror from

Tutanchamun'sTomb Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The notion of akh, often translated as (effective) spirit, pointed toward many different meanings, such as the identity of the transfigured dead as well as that of living persons who acted efficaciously for (or on behalf of) their masters. The akh belonged to cardinal terms of ancient Egyptian religion and hence is often found in Egyptian religious texts, as well as in other textual and iconographic sources. Its basic meaning was related to effectiveness and reciprocal relationship that crossed the borderlines between different spheres. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The akh is included among religious terms connected to the Egyptian conception of human and divine beings, their status, roles, and mutual relationships. Since it was linked to a wide range of ideas and beliefs at the core of ancient Egyptian religion, this term and its derivatives occur regularly in Egyptian religious texts, as well as in textual and iconographic sources of other character.

“Although the akh—like the words ka and ba—lacks an exact counterpart in any modern language, it has often been translated as “spirit”, leaving aside the impossibility to find exact counterparts for words in different languages. The Egyptian term, however, pointed toward many different but interconnected meanings, for instance, the ideas of the transfigured, efficacious, glorious, or blessed dead. The term akh also had to do with the notions of being an intermediator between the living and the divine (see below). The core meaning of akh had to do with the idea of “effectiveness” and mutual relationship or dependence that crossed the borderlines between the human and divine spheres, and between the world of the living and the realm of the dead.

See Separate Article: AKH: MEANING, POWER, SYMBOLS africame.factsanddetails.com

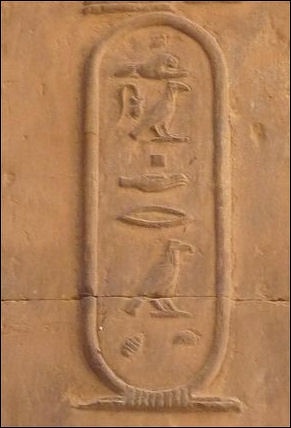

Cartouche

Cathie Spieser, an independent researcher in Switzerland, wrote: “The cartouche is an elongated form of the Egyptian shen-hieroglyph that encloses and protects a royal name or, in specific contexts, the name of a divinity. A king’s throne name and birth name were each enclosed in a cartouche, forming a kind of heraldic motif expressing the ruler’s dual nature as both human and divine. The cartouche could occur as a simple decorative component. When shown independently the cartouche took on an iconic significance and replaced the king’s, or more rarely, the queen’s, anthropomorphic image, enabling him or her to be venerated as a divine entity. Conversely, the enclosure of a god’s or goddess’s name in a cartouche served to render the deity more accessible to the human sphere. [Source: Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

cartouche at Kom Ombo

“The cartouche derives from the Egyptian shen-ring, a hieroglyphic sign depicting a coil of rope tied at one end, meaning “ring, circle,” the root Sn (shen) expressing the idea of encircling. Symbolically, the cartouche represents the encircling of the created world by the sun disc—that is, the containment of “all that the sun encircles.” Originally, the shen-ring was probably an amulet formed from a length of papyrus rope looped into a circle with an additional binding. The cartouche is an elongated shen-ring, extended to accommodate and magically protect a royal name.

“The convention of enclosing the king’s name in a cartouche initially appeared on royal monuments and may possibly date back as early as the First Dynasty, although there is currently little conclusive evidence to support this supposition. Recent work on early writing may well shed light on the question. The cartouche was first used to enclose the king’s birth (given) name. The earliest attested example of an enclosed birth name— that of Third Dynasty pharaoh Huni, found on a block at Elephantine—is doubtful. Well attested, however, are examples on royal monuments of Sneferu (Fourth Dynasty) and his successors. By the middle of the Fifth Dynasty, during the regency of Neferirkara, the newly instituted throne name is also enclosed within a cartouche.

“The first occurrence of the use of cartouches to enclose queens’ names appears in the Sixth Dynasty. At this time we find the birth names of Ankhnesmeryra I and her sister Ankhnesmeryra II, also called Ankhnespepy—both wives of Pepy I— partially contained: cartouches enclose only the components “Meryra” and “Pepy,” these being the king’s throne and birth names, respectively. This convention reflects the queen’s position as “king’s wife,” but may further indicate, in a sense, that the king’s cartouche also became a part of the name of the queen, perhaps opening the way for queens to have their own names placed in cartouches. The name of queen Ankhnesmeryra I occurs in a private burial monument; that of Ankhnesmeryra II is found in her small pyramid at Saqqara. From the Middle Kingdom onward, cartouches enclosed the queen’s entire birth name; the birth name remained the only queen’s name to be enclosed by a cartouche. Occasionally epithets (both royal and non-royal) or god’s names could also be included.

See Separate Article: CARTOUCHE: MEANING, PURPOSE, VENERATION africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024