Home | Category: Religion and Gods

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN RELIGION

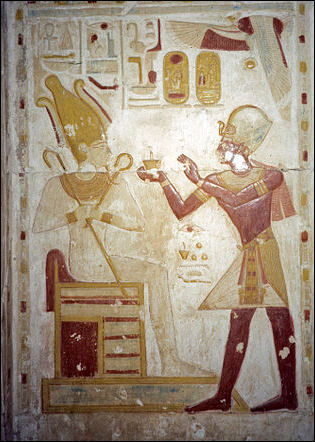

Orisis The ancient Egyptians were an immensely religious people. Herodotus said they were the most religious people known and that Egypt had more monuments than any other place in the world. It has been argued that religion drove the ancient Egyptians to achieve what they did.

The ancient Egyptian religion is difficult to understand. It is full of contradictions, strange unfathomable rituals and complex texts. The worship of Isis, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, continued until at least the sixth century A.D.

The archaeologist Michael Poe wrote: "Throughout” Egypt's “4,000 odd year old history there is no systematic account of the doctrines used. Different men living at different times do not think alike; and no college of priests had formulated a system of beliefs that was received by all clergy and laity alike. 42 nomes, 42 religions in 4,000 years! Changes were extensive; differences, even in the same periods, were great. But all had one thing in common: a concept of Organic Totality” — which encompasses the physical environment, human organizations, conscience, language and ultimate goals.

Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote on the Ancient Near East Page.“Egypt did not have a central dogma or sacred book. But the one thing that prevented them from losing their individuality and from coalescing into a common unit is the belief in more than one set of gods. Egyptian religions were both personal and nationalistic. It was personal to each individual or family; private and interwoven with a sense of personal right and wrong; with a personal shrine or "niche" in every house to the personal gods or goddesses. It was nationalistic because usually the place of the national seat of government determined the overall thought and public morality of the period.) [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many” by Erik Hornung (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Search for God in Ancient Egypt” by Jan Assmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Religion of Ancient Egypt: An In-depth Study, Over 200 Photographs” by Lucia Gahlin (2011) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion” by Donald B. Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion” by Stephen Quirke (1992) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptians, Religious Beliefs and Practices” by Ann Rosalie David (1982) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World” by Gerald Massey (1907) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Flinders Petrie (1906) Amazon.com;

“Christianity: An Ancient Egyptian Religion” by Ahmed Osman (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity” by Moustafa Gadalla (2007) Amazon.com;

Pyramid Texts and Early Ancient Egyptian Religious Texts

Pyramid text

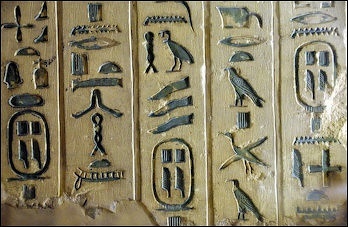

The Pyramid Texts are among the oldest texts. They were based on inscriptions of spells found in the burial chambers of the pyramids and dated to around 2600 B.C. They were like an early compendium on the Egyptian religion. The Amduat (“The Book of the Netherworld”) and The Book of the Dead are based on them. A typical spell from the Pyramid Texts went: “O Osiris, the King, may you be protected. I give to you all the gods, their heritages, their provisions, and all their possessions, for you have not died."

The Pyramid Texts are ascribed to Unis (2345–2315 B.C.), also spelled Unas, the ninth and last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom. According to Archaeology magazine: The Unis pyramid at Saqqara was also the smallest one ever built during the Old Kingdom, but inside the modest complex was an innovation that would endure for thousands of years.Unis commissioned a series of sacred formulas or spells known as the Pyramid Texts to be carved on the walls of his burial chamber. These include instructions for properly carrying out a funeral and references to the sun that were both codified earlier, perhaps during the 4th Dynasty. But most of the text is devoted to the worship of Osiris. By this time, the god of death had finally become more important than the sun god, upon whose power the earlier 5th Dynasty rulers had relied. Nevertheless, the Pyramid Texts were still intended to reinforce the pharaoh’s legitimacy. “On a symbolic level, the king needed to come up with a new unique form of his extraordinary standing, being a deputy of the gods on Earth,” says Bárta. “The Pyramid Texts were just such a means of achieving this.” Variations of the Pyramid Texts would be included in the tombs of the 6th Dynasty pharaohs, and even in the pyramids of their queens. Within just a few hundred years, the formulas and spells of the Pyramid Texts had spread beyond royal burials, and were inscribed on the coffins of officials throughout Egypt. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

The Pyramid Texts evolved into the Coffin Texts , dated to around 2000 B.C., a collection of spells placed by artisans in wooden coffins. Neither the Pyramid Texts nor the Coffin Texts ever appeared in book form. They were written on tomb walls or coffins.

Amduat (“The Book of the Netherworld”) was a narrative that described the daily journey of a dead pharaoh through the netherworld on a boat of the sun god Re, and his victory over dangers and obstacles to rise again the next morning. The book was originally restricted to use by the pharaoh and those that attended him.

Other important texts included: 1) The Book of Two Way , describing the underworld as composed of canals, streams, islands, fires and boiling water; 2) The Book of Gates , describing the night journey of Osiris and the rewards and punishments for inhabitants of the Underworld; 3) The Book of That Which Is , describing the 12 sections of the Underworld, each related to an hour of the Night; and 4) The Book of Adophis , detailing the battle between the sun god Ra and the giant serpent Apophis.

Egyptian Cosmology and Akhu

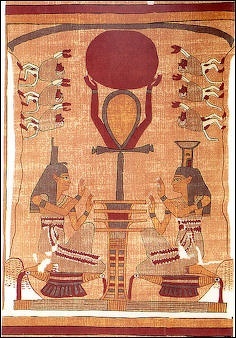

Ankh Djed and Sun from the Book of the Dead

On Egyptian religion and cosmology and the akhu, Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The three levels or realms of created cosmos (the earth, the sky, and the underworld) converged at the horizon (akhet). The latter term represented the junction of cosmic realms, and it was also viewed as the place of sunrise, hence the place of birth, renewal, and resurrection. Moreover, it was considered a place where divine beings (both gods and the blessed dead) dwelt and from whence they could venture forth. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The notion of the akh has often been translated as “spirit” or “blessed dead,” though the range of its aspects and powers covered also the meanings of “superhuman power” or “sacred mediator”. The Egyptians considered their blessed and influential dead—the akhu—as “living,” i.e., as “the resurrected”; however, human beings had to be transfigured and admitted into this state. Finally, the akh represented a mighty and mysterious entity that was part of the divine world and yet still had some influence upon the world of the living. They could interact with the living by means of superhuman powers and abilities, guard their tombs, punish intruders or wrongdoers, help in cases when human abilities were insufficient, or act as mediators between gods and men.

“In a parallel with the gods and people, a certain hierarchy existed even within the society of spirits. The deceased king thus represented “the head of the akhu” (Pyramid Texts Spell 215, §2103). According to Egyptian cosmology and mortuary texts, the akhu were “born” or “created” at the horizon, where they also dwelled and where they came from. Some sources (e.g., the so-called Book of the Dead), thus, use an expression jmyu akhet (“those who dwell in the horizon”) to denote or describe the blessed dead. Since the akhu were dependent on ritual actions performed by the living, a mutual relationship and cooperation between men and akhu formed one of the pillars of ancient Egyptian religion.”

Gods, Akhu, and Men

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The Egyptians divided the cogitative beings of the world into different types or categories with regard to the degree of their power and authority. This concept occurred for the first time in Middle Kingdom texts and remained in use until the Roman Period. The division of the categories of beings appears also in the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead, as well as in hymns, ritual or educational texts, and onomastica. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The highest position among the beings was held by the gods (nTrw) and the lowest was reserved for human beings (rmT; occasionally subdivided into pat, rxyt, and Hnmmt), or rather the living (anxw tp tA). The boundary sphere between the human and divine worlds was believed to be operated by semi-divine entities or beings with super-natural status and power, such as the demons and the blessed and the damned dead (the Axw and the mwtw), and by the supreme intermediator, the king. Royal annals or king-lists, which sometimes record divine dynasties and rule of the akhu prior to the historical or at least legendary rulers, witness a very similar concept of hierarchy.

“As to the role of the akh among other terms relating to composites, parts, or manifestations of human and divine beings, unlike the body, the ka, the shadow, it was never believed to represent part of the composition of a human entity. The Egyptians considered their blessed, efficient, and influential dead (i.e., the akhu) as “living,” that is, as “resurrected.” According to Egyptian ideas on life, death, and resurrection, a person did not have an akh, he or she had to become one. Moreover, this posthumous status was not reached automatically. Human beings had to be admitted and become transfigured or elevated into this new state. The dead became blessed or effective akhu only after mummification and proper burial rites were performed on them and after they had passed through obstacles of death and the trials of the underworld. Thus, only a person who lived according to the order of maat, who benefited from rituals or spells called the sakhu—those which “cause one to become an akh” or the “akh-ifiers” —and was subsequently buried, could be glorified or become transfigured into an akh. Late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period offering formulae attest the idea that a person was made akh by the lector priest and the embalmer. After reaching this status, the dead were revived and raised to a new plane of existence. The positive status of the mighty and transfigured akhu was mirrored by a negative concept of the mutu who represented those who remained dead, i.e., the damned.

“From a cosmological point of view, the horizon (e.g., akhet) played a very important role in the process of becoming an akh. Although it mainly represented the junction of cosmic realms (the earth, the sky, and the netherworld), the horizon was a region in itself. The akhet was believed to be the place of sunrise, hence the place of birth, renewal, and resurrection, and, moreover, it was considered a region where divine and super-human beings dwelt and from whence they could venture forth. Thus, the horizon represented the very place of “birth” or “creation” of the akhu. In the Book of the Dead, the blessed dead were denoted as “those who dwell in the horizon”.

“Besides the above-mentioned moral and ritual prerequisites, one’s intellectual power and knowledge as well as his or her social status might have been important factors in reaching the akh-status. In a parallel to the world of the gods and human beings, a certain hierarchy and stratification existed even within the society of the akhu. Thus, the (deceased) king or Horus represented “the head of the akhu” (Pyramid Text §§ 833, 858, 869, 899, 903, 1724, 1899, 1913 - 1914, 2096, 2103) or was considered the first of the akhu, the “akh akhu”.”

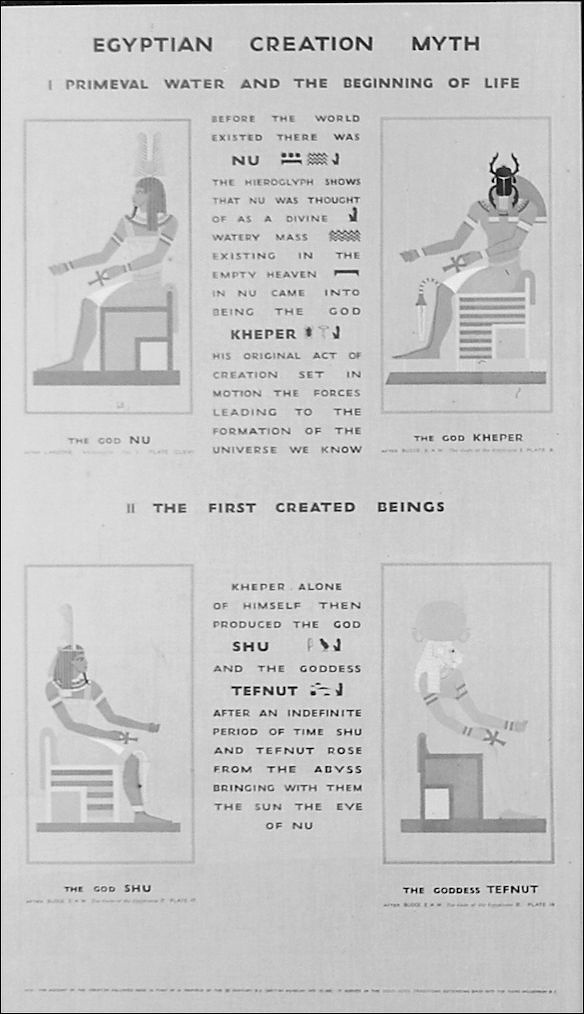

Egyptian creation myth

Theodicy: Good and Evil, Order and Chaos in Ancient Egyptian Religion

A prominent theme in mythological descriptions of the struggle between order and chaos Theodicy is the enquiry of the justness of the divine. Roland Enmarch of Liverpool University wrote: “A theodicy is an attempt to reconcile belief in divine justice with the existence of evil and suffering in the world....Aawareness of suffering and the problematization of evil are central to many diverse religious and philosophical traditions, including those of ancient Near Eastern cultures. [Source: Roland Enmarch, Liverpool University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Several areas of Egyptian written discourse (primarily mythological, literary, and biographical) explicitly address theodicean topics, advancing a range of theodicean positions. In Egyptian mythology, good and evil are respectively identified with cosmic order (Maat) and chaos (Isfet), an opposition attested as early as the Old Kingdom, where it is featured in the Pyramid Texts. Chaos preceded the creation of the ordered cosmos and continued to threaten its existence. The divine world was not transcendent, but was engaged in this ongoing struggle to maintain order. In this scheme, evil and chaos were inherent features of the cosmos, and humanity’s role was limited to the dutiful maintaining of maat on earth.

“Another strand of theodicean discourse, which first becomes prominent in the Coffin Texts and in Middle Egyptian poetry, focuses more on the relationship between humanity and the divine. The deity whose justice is in question here usually assumes the role of solar creator god. According to these texts, humanity chose to behave chaotically and rebelled against the creator god despite his benevolent treatment of them. After defeating this rebellion, the creator god withdrew from direct contact with humanity; it is this distancing of the creator god that permits the existence of suffering in the world. Two of the clearest references to this rebellion are in the declaration of the creator god in Coffin Text spell 1130, first attested in the 11th Dynasty, and in the Book of the Heavenly Cow, a mythological text first attested in the late 18th Dynasty.”

Egyptian View on Theodicy

Roland Enmarch of Liverpool University wrote: “The interplay between the cosmic and anthropocentric conceptions of evil—in particular, the question of the balance between human and divine responsibility for suffering on earth—underlies most Egyptian theodicean discourse. In earlier periods the cosmic and political aspects of the struggle between order and chaos predominate, but as time progresses there is an increasing emphasis on the everyday human experience of imperfection and injustice in life on earth, and the reasons for it. [Source: Roland Enmarch, Liverpool University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The Egyptians’ essentially negative cosmology, and the negative evaluation of human nature arising from it, potentially absolved the gods of blame for the world’s imperfections by inculpating humanity. Theodicean interpretations of divine action have implications for social structure and tend to encourage normative cultural and political values. From at least the Middle Kingdom onwards, theodicy formed the basis of the legitimation of the Pharaonic state, where strong and sometimes violent action on the part of the king was required in order to curb humanity’s chaotic tendencies. In accordance with this cosmic framework, untoward political events in Egyptian history, such as rebellions, the Hyksos dominion, or the defunct reforms of the Amarna period, were portrayed in subsequent royal inscriptions as aberrant outbreaks of chaotic behavior.

“The correct human response to this state of affairs was to demonstrate conduct in accordance with the ideal of maat, one component of which was loyalty to the Egyptian state. In earlier periods, such behavior was assumed to lead to success in this life, as stressed, for example, in the Middle Egyptian Loyalist Teaching, and to being judged righteous after death. The concept of a posthumous moral judgment, attested most famously in Book of the Dead spell 125, forms another implicit theodicean argument: regardless of suffering in this life, good conduct would be rewarded by the gods in the next. Coffin Text spell 1130 underlines this by listing, as one of the creator god’s four “good deeds” for humanity, the fact that he promoted piety by making them mindful of death.

“The most direct critique of this view of the creator god occurs in another Middle Egyptian poem, the Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All, where a human sage accuses the creator god of being too distant from human affairs and of not distinguishing the meek from the fierce. The implication is that it is the fault of the creator if the creation is deficient. An underlying question is whether human beings are condemned by fate to behave chaotically and receive punishment , or whether they have free will, a theme more directly addressed in later periods (on destiny and free will). Although Ipuwer focuses on problematic aspects of normative ideology, it does not ultimately undermine that ideology but instead forms a plea for closer and more discriminating divine (and royal) intervention in the world, to ensure that justice really is done.”

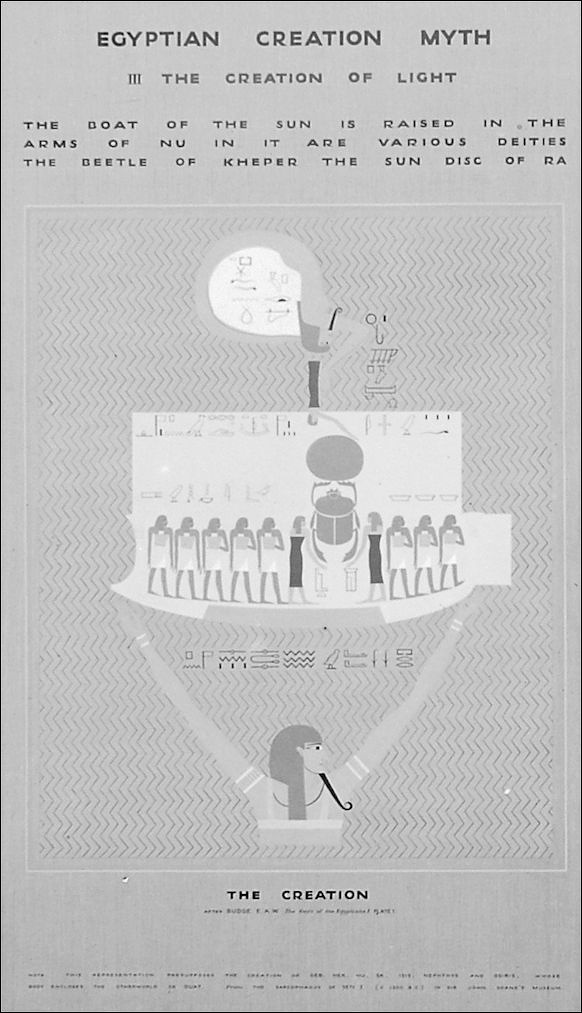

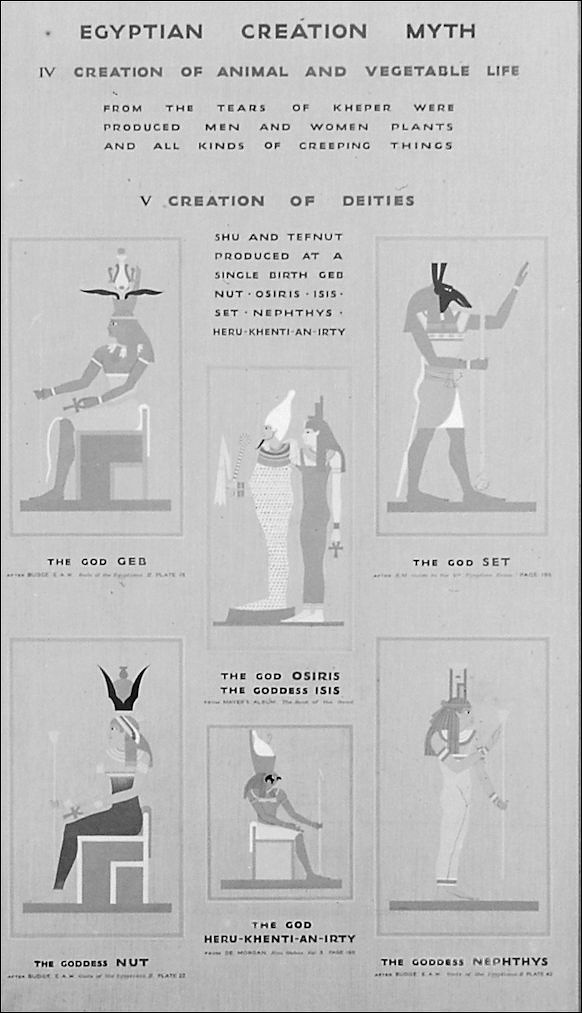

Evolution of Egyptian Cosmological Traditions

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “According to the Heliopolitan Tradition, the world began as a watery chaos called Nun, from which the sun-god Atum (later to identified with Re) emerged on a mound. By his own power he engendered the twin deities Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), who in turn bore Geb (earth) and Nut (sky). Geb and Nut finally produced Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys. The nine gods so created formed the divine ennead (i.e. company of nine) which in later texts was often regarded as a single divine entity. From this system derived the commonly accepted conception of the universe represented as a figure of the air-god Shu standing and supporting with his hands the out-stretched body of the sky-goddess Nut, with Geb the earth-god lying at his feet. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The second cosmological tradition of Egypt was developed at Hermopolis, the Capital of the Fifteenth Nome of Upper Egypt, apparently during a time of reaction against the religious hegemony of Heliopolis. According to this tradition, chaos existed at the beginning of time before the world was created. This chaos possessed four characteristics identified with eight deities who were grouped in pairs: Nun and Naunet, (god and goddess of the primordial water), Heh and Hehet, (god and goddess of infinite space), Kek and Keket, (god and goddess of darkness), and Amun and Amunet, (god and goddess of invisibility). +\

“These deities were not so much the gods of the earth at the time of creation as the personifications of the characteristic elements of chaos out of which earth emerged. They formed what is called the Hermopolitan Ogdoad (company of eight). Out of chaos so conceived arose the primeval mound at Hermopolis and on the mound was deposited an egg from which emerged the great sun-god. The sun-god then proceeded to organize the world. The Hermopolitan idea of chaos was of something more active than the chaos of the Heliopolitan system; but after the ultimate triumph of the latter system, a subtle modification (no doubt introduced largely for political reasons) made Nun the father and creator of Atum. +\

“The third cosmological system was developed at Memphis, when it became the capital city of the kings of Egypt. Ptah, the principal god of Memphis, had to be shown to be the great creator-god, and a new legend about creation was coined. Nevertheless, an attempt was made to organize the new cosmogony so that a direct breach with the priests of Heliopolis might be avoided. Ptah was the great creator-god, but eight other gods were held to be contained within him. Of these eight, some were members of the Heliopolitan Ennead, and others of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Atum, for example, held a special position; Nun and Naunet were included; also Tatjenen, a Memphite god personifying the earth emerging from chaos, and four other deities whose names are not certain. They were probably Horus, Thoth, Nefertum, and a serpent-god. Atum was held to represent the active faculties of Ptah by which creation was achieved, these faculties being intelligence, which as identified with the heart and personified as Horus, and will, which was identified with the tongue and personified as Thoth. +\

“Ptah conceived the world intellectually before creating it 'by his own word'. The whole Memphite theology is preserved on a slab of basalt now exhibited in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. It was composed at an early date, and committed to stone during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty by the order of King Shabaka. Unfortunately, this stone, the so-called 'Shabaka Stone' was subsequently used as a nether mill-stone and much of the text has been lost. The document known as the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus includes, among other religious texts, two monologues of the sun-god describing how he created all things. +\

Memphite Theology and the Shabaka Stone

The Memphite Theology predominated in ancient Egypt during the early centuries of Egyptian unification, but was replaced as the official, Pharoanic cult by the Heliopolitan perception which predominated intermittently after around 2700 B.C. According to Encyclopædia Britannica,in the Egyptian document known as the “Memphite Theology,” “Ptah created humans through the power of his heart and speech; the concept, having been shaped in the heart of the creator, was brought into existence through the divine utterance itself. In its freedom from the conventional physical analogies of the creative act and in its degree of abstraction, this text is virtually unique in Egypt, and it testifies to the philosophical sophistication of the priests of Memphis.

Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote: “The Shabaka Stone, discovered in the 19th century, contains the text of a document from around 28-2700 B.C.. In the 8th century B.C. the Pharaoh, Shabaka, ordered it transferred from leather to stone to preserve it. The center section was later destroyed by farmers who used the stone as a millstone to grind grain. The text contains most of a theology from the city of Memphis. The Memphite theologians based their thought in the recognition of Ptah, the Great Invisible One, the Axis of Heaven, as the One God, though he could appear in any of his aspects. The Great God, Ptah, was the only God. However, parts of himself were granted autonomous, separate existences, but were reassumable into Ptah. Ptah, the Great Invisible One, lived at that point in the northern sky [the north celestial pole was not occupied by a star] around which all the stars revolved. The sun, the moon, and the planets did not appear to obey him. Therein lay an immense theological flaw. Memphite astronomers might point out that these apparently independent movements of Sun, Moon, and the planets exhibited recurrent patterns against the backdrop of the stars which revolved around Ptah, and that this confirmed Ptah's superiority. [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT \=/]

“The theologians of Memphis affirmed a belief in a “heart-centered intellect.” The Shabaka Stone clearly indicates a belief that the Eyes and Ears and Nose report information to the heart which then deliberated before announcing its response by way of the tongue. The Memphites refer to three of the "five senses" recognized by moderns. This reflects a division of the "senses" into at least two categories: 1) Sight, Sound, and Smell are extra-personal senses. They function through the Space which separates the person from the item perceived. Each has its peculiar limitations governed by the perceptual medium within which it operates, but they have the common ability to function over Distance. 2) Touch and Taste function only when there is physical contact between the perceiver and the perceived. Perhaps the categories should be called Sensory and Sensual. Creation became by way of the Word. What the Heart of Ptah thought and the Tongue of Ptah announced came into Being. The Tongue of God performed the creative act after the Heart [Mind] of God conceived it. “ \=/

Shabaka Stone

Heliopolitan Scheme and the Origin of Egypt’s First Gods

The Heliopolitan Scheme was a religious concept elaborated by the priests of Heliopolis, a religious center now underneath a suburb of Cairo. Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote: “The theology of Heliopolis recognized the aboriginal existence of God and Entities sometimes spoken of as if divine. These were the: Primordial Entities; a) Nun, the Universal Water, a metaphor of the Womb, and b) Apophis, the Night, the Encircling Serpent. This was a metaphor of the placenta and/or the umbilicus. Apophis was also the limit of the universe: the black deep beyond the stars. Atum pre-existed and co-existed inside Nun, and brought himself into consciousness. He was the first, and ALL. [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT \=/]

“The Gods of Heliopolis. Atum contained All that would be. There became God's: 1) Eye. Its visible self was the Sun and it was called by many names, including Re or Ra, Amon Re/Ra and Aten. Atum's Hearing alerted the Heart of God; Seeing informed it. Eye frequently displaced Atum In Pharoah's favor. Atum might also project Aspects of itself through Eye, such as Sekhmet, the Storm, and Hathor. Hathor was, and was motivated by, Passions such as Love and Hate, and by considerations of fertility. Atum was an Androgyne, the Great He-She.

“The Hand of Atum. Finding himself alone, Atum used his hand and begat, then brought out of himself, the first generation of Gods: a) Shu [Air], and his sister/wife Tefnut [Ma'at/ Mayet]. The root meaning of Ma'at is right-thinking or Order, but she was also Space. They then wandered off into the endless body of Nun. Atum sent Eye to find them and return them. While Eye was gone, Atum created a second eye, possibly the Moon. When Shu and Tefnut returned, Tefnut gave birth to b) Geb [Earth], and his sister/wife b) Nut [Sky]. Geb and Nut were born in sexual embrace. Shu forcibly interposed himself between them, thus separating Earth from Sky. Nut gave birth to two sets of twins: d) Osiris [the Nile, God of the Dead] and his sister e) Isis, who was his wife [the Fertile soil, the star Sirius]; f) Seth [Disorder, Foreign Places], brother to Nepthys, his wife, and to Osiris and Isis. The son of Isis and Osiris was g) Horus [the Pharaoh, the Fruit of the Land]. An older God, h) Thoth, who was reborn as the son of Horus and Seth, was the Law [of God], the Word [of God], the Seed [of God]. \=/

By the time of Herodotus the Temple in Heliopolis was devoted to Ra. Probably the largest temple in the world, it was about 2/3 of a mile long, and a 1/4 of a mile in width. The courtyard was made with polished black basalt stones, so polished that it reflected the stars above and made it look as if one were walking amidst the stars. In the middle of the courtyard was a full size tree, its trunk and branches were made of Lapis Lazuli,its leaves of Turquoise.” [Source: Michael Poe]

See ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Horus Versus Seth and Pharaonic Rule

Horus and Seth crown Ramses III

On the fight between Horus and Seth at the beginning of creation, Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote: “Father Geb faced a unique problem. Atum had resigned his rule to his only son, Shu; Shu in turn gave way for his only son, Geb. Geb had two sets of twins from Nut's one pregnancy. When it came time for him to turn over control of earth [EGYPT], he had two sons from which to choose the next ruler. Some stories suggest he may have divided Egypt; others say he gave it all to Osiris and gave the rest of the world to Seth. Whatever the circumstance may have been, Seth was unhappy with his lot. He murdered his brother, Osiris; cut his body into small pieces, and threw them into the NILE. There, Osiris merged with, and became the River. Isis, assisted by her sister, Nepthys, found all the pieces of Osiris except the phallus. Isis hovered over him imploring him to arise and impreg-nate her. Miraculously, Osiris did revive, and did impregnate his wife before passing to the West, the home of Atum, where he became the Spirit in whom the souls of the righteous dead would eventually find salvation. [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT \=/]

“In term, Isis gave birth to Horus. She hid him from his uncle, Seth, until he was eighteen. Then she presented Horus to the Council of the Gods arguing that, as the only son of Osiris, Horus ought to be given his father's realm [Egypt]. Geb was unable to decide whether the young Horus or the older and stronger Seth should rule. There followed a series of contendings between the ex-ruler's brother and his son to determine which of them was best suited to rule Egypt. In the process, Seth was tricked into admitting that a son's rights of inheritance took precedence over the rights of a brother; and into the appearance of having dishonored himself. As a result of these contendings, the following conventions evolve.

“1) Horus is always Pharaoh, and Pharaoh was King of Egypt by Right of Divinity. (In actuality, not all Pharaohs claimed to be Horus; some identified with Seth, especially if they were involved with foreign lands or their capitals lay in Seth's land; others identified with their own preferred gods.) The idea of a Divine King persisted in the Mediterranean basin until the triumph of monotheistic religions more than 3400 years later. 2) Pharaoh, at first possessed sole right to enter Heaven, but by 2200 B.C. the spiritual dynamics of Salvation were understood and the Democratization of Heaven completed.

“3) The Rule of primogeniture was another victor in the struggle between Horus and Seth for the birthright of Osiris. Horus, Isis, and their supporters used the argument that Osiris, the first born son of Geb, rightfully owned Egypt and that his Domain should pass intact to his Son, not to his brother. Horus' victory was, retroactively, a victory for Osiris' contention in his earlier quarrel with Seth. The Institution called Primogeniture has endured for more than five thousand years, but has declined in social acceptance with the decay of the Institution called the Nobility.”

Democratization of Heaven in Ancient Egypt

Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote: “The phenomenon called the Democratization of Heaven took place during an Egyptian Dark Age called the First Intermediate Period, ca.2400-2200 B.C.. Previously, Pharaoh, because he was the incarnation of Horus, had a right to ascend to Heaven at death. His soul returned to Osiris, but retained its Earthly identity as well. Other Egyptians could acquire Heaven only at the invitation of Pharaoh, whom they would serve in death as they had in life. Some local theologies had their own "heavens," but only after the Democratization were they all joined into the "national" heaven. [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT \=/]

“By 2200 B.C., a refined understanding of the dynamics of salvation allowed all Egyptians an independent right to Heaven. Horus was continually reincarnated in each new Pharaoh. In turn, Horus extended his Soul to each Egyptian. Each Egyptian possessed not only his Horus-given Soul, but also a second Soul which contained his/her individuality. If the proper mortuary rituals were performed at death, the person's identity-soul was carried by his or her Horus-given Soul to a union with Osiris, where the dead merged with and became Osiris. At the end of time, when Atum resorbs all his creations into himself, only Atum, Osiris, and Horus will retain their identities. But, the souls of all Egyptians who followed the proper death rituals and joined Osiris, will retain their identities as a part of Osiris and remain forever One with God. \=/

“This complex salvationist theology only worked in Egypt because it was tied inextricably to the life cycle of the Nile [Osiris]. Annually and predictably as his wife, Isis, in her celestial form as Sirius, hovered over him, Osiris rose from death and fertilized Isis, in her aspect as the flood-plain made rich and black by his floodwaters. Their son, Horus, grew abund-antly from their co-mingling. He was the life in the land, the Spirit incarnated in the person of Pharaoh. Though Horus wore many bodies in his aspect as God-King of Egypt, he remained the Horus. His human heirodules [Pharaohs] merged with him, but retained their autonomous divinity, and through him ascended to Osiris. This dynamic made possible a perception of Salvation as the transition from the Physical Realm to the Spiritual Realm.” \=/

Heliopolis — Ancient Egyptian Mecca

For more than two millennia, Heliopolis was the center of Egyptian religion. Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: Ancient Egyptians believed the world began on a low hill just outside modern-day Cairo. There the sun rose for the first time and made order out of a roiling sea of elemental chaos. There the Egyptian creator, Atum, and sun god, Ra, first appeared, and there they held court for millennia. And there the Egyptians built their most enduring sacred site, a city known today by its Greek name, Heliopolis, or City of the Sun. At the center of the city, contemporaneous sources and recent archaeological excavations show, was the Temple of the Sun. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

“Egyptians worshipped at Heliopolis over the course of countless lifetimes and thousands of years. The earliest known temples there date back nearly 4,600 years, to the first days of Egypt’s pyramids. Inscriptions reveal that generations of pharaohs bolstered their claim to have descended from Atum and Ra by building grand shrines there. At its peak around 1200 B. C. , the holy site was marked with dozens of colossal obelisks.

“Heliopolis was known far and wide in antiquity. Called On in Hebrew, the city is mentioned multiple times in the Old Testament. It also served as a reference point for other Egyptian sacred sites. Although Thebes, Egypt’s capital during the Middle and New Kingdoms (ca. 2030–1070 B. C. ), is now far better known, ancient Egyptian sources referred to it as the “Heliopolis of the South,” and its temples were modeled on those at Heliopolis. Even in its final centuries, Heliopolis was a popular destination supposedly visited by the Greek philosopher Plato, according to an account written four centuries later by the geographer and historian Strabo. Strabo also includes a first-person account of his own visit to the site’s nearly deserted ruins in his book Geographica.

“Both physically and theologically, Heliopolis was at the heart of Egyptian religion. It was both city and temple, every corner of it holy, but also filled with everyday activity. “You can compare it to the very center of Vatican City,” says archaeologist and University of Leipzig Egyptian Museum curator Dietrich Raue. “Everyone inside the city was somehow connected to the sun cult or temple. ”

“Yet today, Heliopolis is virtually unknown. After almost two and a half millennia of continuous worship there, the importance of its temples declined. By the second century B. C. , the city was abandoned, for reasons archaeologists are still trying to discern. It was subsequently plundered and stripped of anything that could be burned or reused. Beginning in the late Roman period, nearly all of its limestone architecture was carted away to build Cairo, leaving little to see above the surface. Over time, most of the city’s obelisks were removed, carried off first to decorate Alexandria, and then to Rome, Paris, London, and even New York. Only one still stands at the center of the site, a 68-foot-tall red granite monument erected by Senwosret I around 1950 B. C. that juts out of the ground in the impoverished Cairo neighborhood of Matariya like a hieroglyph-inscribed spike.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Eternal City” by Andrew Curry in Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024