Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

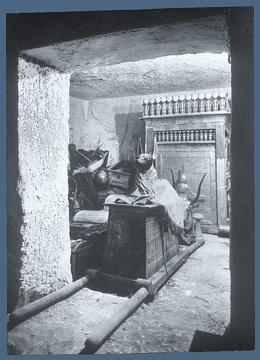

Howard Carter opening Tutankhamun's coffin Egypt's monuments that are with us today are the result of the presence of stone to build them and a desert climate that has preserved them. The Phoenicians were almost as great of civilization but little remains of their civilization because it was largely built from wood. Egypt’s leading archaeologist, Zahi Hawass, estimates that only a third of treasures that lie buried in Egypt have been found.

The climate of Egypt is so dry and rain is so rare in Egypt that millennia-old perishable items like papyrus scrolls have been preserved. Egypt's sands have preserved many monuments. The Sphinx would be in much worse condition were it not buried for a long time.

The great Greek 5th century B.C. historian Herodotus devoted nearly all of Book 2 of “History" to describing the achievements and the curiosities of the Egyptians. On the Egyptian customs Herodotus reported "In any home where a cat dies" the residents "shave off their eyebrows" and “sons never take care of their parents if they don’t want to, but daughters must whether they like it or not." He also noted “Women urinate standing up, men sitting down.” More on Herodotus, See Greeks

Initially, in the 19th century, Egyptian didn't care much for archaeological treasures. They were amendable to get rid of "ancient debris" such as the Rosetta Stone and the obelisk of Luxor. Many archaeological sites such as the ancient capital of Memphis in Cairo now lie under under sprawl.

Law 3 of 2010 on Protecting Antiquities, amending Law 117 of 1983, governs the issue of protecting antiquities, which includes historical sites. Under Law 3 of 2010, the Council of Antiquities is the government agency responsible for providing protection to historical sites, including historical cemeteries. The Council has the authority to confiscate and return any pieces of antiquities taken illegally from historical sites. The Law allows the Council to lead discovery expeditions to explore antiquities under and above the ground. Finally, the Law imposes the penalty of imprisonment and fines on violators. [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2014 ||]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Kathryn A. Bard Amazon.com;

“Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Steven Blake Shubert and Kathryn A. Bard (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology” by Ian Shaw and Elizabeth Bloxam (2020)

Amazon.com;

“Treasures of Egypt: A Legacy in Photographs from the Pyramids to Cleopatra” by National Geographic (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, c.10,000 to 2,650 BC” (Cambridge World Archaeology) by David Wengrow (2006) Amazon.com;

”Travels in Egypt and Nubia: (Expanded, Annotated)” by Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Ancient Egypt: Beyond Pharaohs”

by Douglas J. Brewer (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Many Histories of Naqada: Archaeology and Heritage in an Upper Egyptian Region” (GHP Egyptology) by Alice Stevenson and Joris Van Wetering (2020) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Egyptian Pottery, Volume 2: Naqada III - Middle Kingdom” (Aera Field Manual Series) by Anna Wodzinska (2011) Amazon.com;

“Experiments in Egyptian Archaeology: Stoneworking Technology in Ancient Egypt”

by Denys A. Stocks Amazon.com;

“Egyptology: Search for the Tomb of Osiris” by Dugald Steer (2004) Novel Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Khamwese, the Famous Priest and First Egyptologist

Khaemwise, a son of Ramses II, pursued a career in the priesthood of Memphis and devoted himself to the study of hieroglyphs and antiquities. He also designed the Serapeum, the catacomb for the sacred Apis bulls in the desert at Saqqara. As a result of his interests and activities, Khaemwise has been described as the first Egyptologist in history.

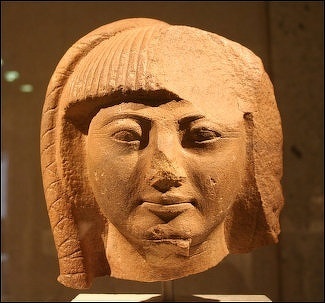

Khaemwise

Dr Joann Fletcher wrote for the BBC: “Although the best known ancient Egyptians are usually pharaohs and queens, one of the most intriguing characters was a prince. The fourth son of King Ramses II by one of his chief wives Isetnofret, Khamwese (c.1285-c.1224 B.C.) was an influential figure in life. For a while he was heir apparent until he predeceased his long-lived father. He also gained a reputation for learning and magic which lasted for more than a thousand years, making him the ideal central character in the story of 'Death in Sakkara'. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“His name-translated variously as Khamwese, Khaemwese, Khaemwise, Khaemwaset-is written with the three hieroglyph symbols featured at various points in the game: the sunrise symbol is pronounced 'kha', the owl 'em' and the sceptre-like sign was here pronounced 'waysi'. Although his name actually means 'Manifest in Thebes', the religious capital in the south of Egypt, Khamwese seems to have spent most of his life at the ancient capital Memphis in the north. |::|

“Born around 1285 B.C., he was well-educated during his childhood and teenage years and chose a career in the clergy. As a priest of Ptah, the creator god of Memphis, he rose through the ranks, working as a sem-priest (a junior rank of priest) and eventually becoming high priest by around the age of 30. His priestly duties gave him access to the finest temple libraries in Egypt, and as he states himself, he was never happier than when reading the works of earlier times. Yet there was also a practical purpose to such antiquarian research, and by finding out about Egypt's previous 1,800 year history, he could reflect past glories on to the current pharaoh, his father Ramses II. |::|

“Khamwese's knowledge of the past also inspired him to study the monuments all around him at Memphis and its nearby cemetery at Sakkara, a vast necropolis of tombs and temples already over a thousand years old. Dominated by the great Step Pyramid of Djoser (c.2650 B.C.), it even attracted tourists in Khamwese's day, some of whom left appreciative graffiti recording their visit. Yet with many of these ancient buildings in states of varying disrepair or ruin beneath Sakkara's drifting sands, Khamwese began a programme of restoration, 'because he loved to restore the monuments of kings and make firm again what had fallen into ruin'. The finished tombs and temples were then inscribed with the name of the monument's original owner, the name of the current pharaoh, Ramses II, and a brief description of the work carried out, inscriptions which have been described as 'the largest museum labels in history'. |::|

“Khamwese also carried out work at Giza, restoring the Great Pyramid built by Khufu around 2580 B.C., and even undertaking excavations at the site. Unearthing a statue of Khufu's son Kawab, he records, 'It was the High Priest and prince Khamwese who was delighted by this statue of the king's son Kawab which he discovered', placing it in a chapel which seems to have acted as a kind of museum for his discoveries, 'because he loved the noble ones who dwelt in antiquity before him, and the excellence of all they made'. |::|

“Yet Khamwese was not the first to excavate or collect antiquities, and as early as c.1402 B.C., King Thutmose IV had excavated the millennium-old Sphinx from the sands of Giza. The next king, Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.), had collected ancient artefacts and ordered the restoration of ancient sites 'after I had found them fallen into disrepair since days of old'. Even Amenhotep's infamous son Akhenaten seems to have had an eye on the past, with a 1,200 year old alabaster bowl made for Khafra, builder of Giza's second pyramid, found in his tomb at Amarna. Nevertheless, it is Khamwese with his all-round antiquarian interests who is known as 'the first Egyptologist'. As scholar John Ray has observed, 'the past fascinated Khamwese, and as a result, Khamwese fascinates Egyptologists, who see him as one of their own'. |::|

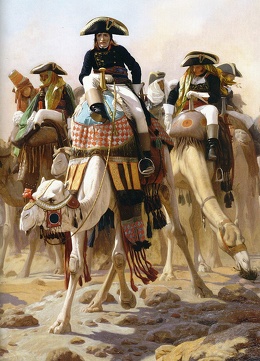

Egyptology and Napoleon

The science of Egyptology began with Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798-1801. The invasion force included 150 scientists, artists geographers, and linguists, and included some of the greatest minds of Europe. They produced 24 volumes of material (published mostly between 1809 and 1824), made some of the first and greatest discoveries of ancient Egypt and orchestrated the massive carrying off of booty and treasure to France.

Napoleon effectively abandoned the crew of scholars and scientists in Egypt and the unexpected result was the establishment of formal archaeology as we know it today.Morgan McFall-Johnsen and Jenny McGrath wrote in Business Insider: Napoleon wanted these "savants," as scientists were called at the time, to focus on projects that could benefit France, such as purifying water from the Nile River, hops-free beer brewing, and better bread ovens. Just a year later, Napoleon secretly returned to France to stage a coup and seize power, leaving his savant squad and 30,000 troops behind. They stayed until defeat forced them to retreat in 1801. [Source: Morgan McFall-Johnsen,Jenny McGrath, Business Insider, January 31, 2024]

While the soldiers fought, some of the savants got busy conducting archaeological surveys. "Very few of the scholars were antiquarians, those quintessentially eighteenth-century characters, mostly wealthy, who filled their curiosity cabinets with strange old objects picked up on their travels, barely understanding what they had," Nina Burleigh writes in her book, "Mirage," about Napoleon's scientists in Egypt. "Collecting old objects without understanding their use or meaning was a pastime for gentlemen, not a scientific undertaking. " In short, these men were approaching the exploration of Egypt with a different attitude that was more scientific.

Egyptology and the French

Frenchmen headed the Egyptian antiquities department until 1952. When the French were ousted by the British, British scientist arrived on the scene. The Rosseta Stone, but little else, was turned over to the British.Great early French Egyptologist included Jean Francois Champollion (1790-1852), who broke the code on the Rosetta Stone; Vivian Denon, who accompanied Napoleon in 1798 and made many sketches of the great monuments; and Aguste Mariett, who helped assemble the Louvre collection, worked as a curator for the Ottoman Turks and established the first museum of Egyptian antiquities in Cairo in 1856. Photographer Maxime Du Camp and writer Gustave Flaubert embarked on their famous voyage to the Middle East in 1849 and traveled down the Nile. Bernardino Drovetti was the French consul general of Egypt. He was a notorious tomb raider and "sold mummies by the pound."

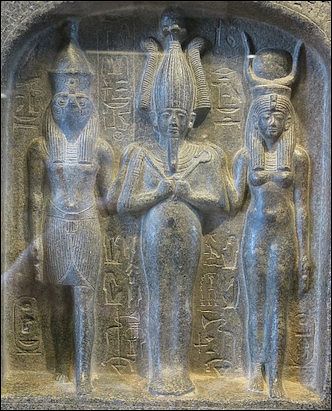

Osiris, Horus and Isis at the Louvre

At the time of Napoleon’s expedition in Egypt, , many Europeans had heard of the Great Pyramids or the Sphinx, but the ancient temples and monuments of Upper Egypt were unknown. Morgan McFall-Johnsen and Jenny McGrath wrote in Business Insider: Dominique-Vivant Denon, an artist and writer, accompanied Napoleon's soldiers up the Nile. He wrote about rounding a river bend to suddenly see the ancient temples of Karnak and Luxor rising from the ruins of Thebes. "The whole army, suddenly and with one accord, stood in amazement. . . and clapped their hands with delight," he wrote, according to Scientific American. Denon returned to France with Napoleon and quickly published a book with his descriptions and drawings, "Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt." That was not enough for Denon, though, who pushed for sending more savants to the Nile to document its monuments in greater detail. [Source: Morgan McFall-Johnsen,Jenny McGrath, Business Insider, January 31, 2024]

Napoleon sent two fresh commissions of savants arrived in Egypt on an archaeological mission in September 1799. This crew of young architects and engineers made careful drawings and measurements of a large number of ancient structures. Their depictions were so faithful that they preserved inscriptions that have since disappeared, according to Scientific American. All these surveys were published in "La Description de l'Egypte," a multi-volume tome that included maps, hundreds of copper engravings, and essays describing what they'd learned about Egypt. It divided Egypt into ancient and modern times, and launched the modern vision of ancient Egypt as we know it today.

"La Description de l'Egypte" was extremely popular. The structures, symbols, and images of ancient Egypt became fashionable features of European art and architecture. Goaded on by Napoleon's savant expeditions, the European fascination with ancient Egypt gave rise to archaeological museums in Europe, beginning with the Louvre opening the first Egyptian museum in 1827. Eventually, this fascination led to the field of Egyptology, which has been a heavy influence in modern archaeology. "Napoleon's scholars and engineers are remembered most as men who helped found archaeology as a science," Burleigh writes.

Exploitation and Politics of Ancient Egyptian Archaeology

Many works of art were snapped up European and American collectors. A 19th century writer wrote of the art market in Thebes: “As workmen, the Copts are perhaps the more artistic. As salesmen, the Arabs are perhaps the least dishonest. Both sell more forgeries than genuine antiquities.” Mummies were unwrapped to look for jewels. Diplomats used their immunity to work as middlemen between looters and collectors.

Beginning in the late 1700s, the Middle East and the Ottoman empire began to occupy a space in the Western imagination. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: What the Grand Tour was to the eighteenth century, the voyage au Levant became for the Romantic generation, a mystical itinerary through Egypt and the Holy Land to the sources of civilization. With the arrival of organized tourism (Thomas Cook offered his first Nile tour in 1869), the pilgrimage of the soul which was the voyage au Levant turned into an exotic vacation.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The European preoccupation with ancient Egypt began in the Napoleonic period. Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt was motivated by a desire to destabilize the British, but when his fleet sank in 1798 at the Battle of the Nile the French rebranded the enterprise as a scientific endeavor. In scientific terms, the French had been successful, it was during this period that they acquired the Rosetta Stone, which they subsequently handed over to the British. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 21, 2019]

As a result of failed political ambitions, there was a frenzy of interest in Egyptian antiquities. Speaking in 2017, museum curator Tom Hardwick said “Ancient Egypt [was] a way of legitimizing interest [in the country] – by using arguments like: ‘then they built pyramids, now they live in mud huts. It’s clever white people who need to look after this’.” The idea of a lost, technologically sophisticated civilization had a certain romanticism and this was only amplified by myths about the “Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb” and the perceived strangeness of ancient Egyptian religion. Combined together these factors made ancient Egyptian artifacts among the most desirable in the world.

It was only in the 1830s, with the awareness of just how many Egyptian artifacts had been exported from the country, that the government stepped in and began to restrict the mining of the country’s non-renewable antiquities reserves. Even then excavations were a financial operation. The renowned archaeologist Flinders Petrie, pioneer of modern archaeological methods, sold futures in order to fund his excavations. The consequences of doing this was that anything he found would be broken up and divided between the museums and collectors who invested in him. The Egypt Exploration Fund, which was founded in the late nineteenth century to “explore, survey, and excavate Egypt” was very explicit about this aspect of their work. Nongbri pointed me to the Secretary's report from 1899-1900, which records that the “distributions” were “a duty which the Committee performs with a full sense of responsibility, especially towards the subscribers in America, with whom we have entered into a formal undertaking that antiquities shall be distributed in strict proportion to subscriptions received.” .

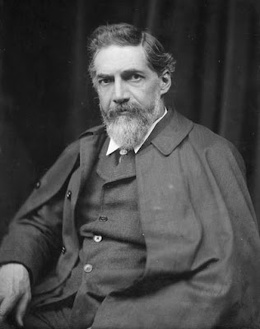

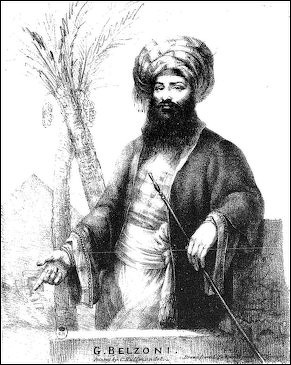

Giovanni Battista Belzoni

Perhaps the greatest rediscover of ancient Egypt was a flamboyant son of a barber named Giovanni Battista Belzoni. Born in Padua, Italy and named after John the Baptist, this six-foot-six former circus giant, who used to carry twelve people around on a stage with a special harness, uncovered many of Egypt's most famous monuments including Abu Simbel, the tomb of Seti I and giant statues of Ramses the Great. [Source: Dora Jane Hamblin, Smithsonian magazine]

After living in Paris and Holland, Belzoni ended up in England where he married an English woman and made a living making fountains with different colored water and playing musical glasses filled with water. While on tour with a traveling circus, which employed his as the "Patagonian Sampson," Belzoni met the an Albanian soldier of fortune named Mohammed Ali, who later would become the leader of Egypt. Ali invited Belzoni to Egypt where the Italian introduced a waterwheel "constructed on the principal of a crane with a walking wheel, in which a single ox by its own weight alone could affect as much as four oxen employed in the machines of the country."

While in Egypt Belzoni was hired by a British general counsel named Henry Salt who urged the former circus strongman to collect antiquities "whatever the expense" for "an enlightened nation.” In Luxor Belzoni met another Italian, Bernardino Drovetti, who had been hired by the French to do pretty much the same thing. Drovetti had established himself at Luxor (his discoveries form the cornerstone of the Louvre Egyptian collection) so Belzoni moved on to the Valley of the Kings where he made two great discoveries — the tomb of Ramses the Great and the tomb of his father Seti I.

Belzoni's Discovers Memnon's Head

Describing his 1816 discovery of the nine-foot-high head of "Young Memnon," now in the British Museum, Belzoni wrote: "I found it near the remains of its body and chair, with its face upwards, and apparently smiling on me, at the thought of being taken to England...my expectations were exceeded by its beauty, but not by its size." Using "fourteen plows...four ropes of palm leaves and four rollers" he managed to move the head only a "few yards" the first day and 50 yards the next day. "To make room for it pass we had to break the bases of two columns." When the Rosetta stone was deciphered it was revealed that the head of "Young Memnon" actually belonged to Ramses the Great.

When a local official told the Egyptian labors not to report to work Belzoni used his bare hands to disarm the bureaucrat of two pistols and a sword, and afterwards "gave him a good shaking." The laborers returned to finish their tasks of carrying "Young Memnon" to the Nile where it was transported by ship to London.

On falling on a heap of mummies Belzoni wrote, "Fortunately, I am destitute of the sense of smelling,” but "I could taste that mummies were rather unpleasant to swallow...I sought a resting place, found one, and contrived to sit; but when my weight bore on the body of an Egyptian, it crushed it like a bandbox...so that I sunk altogether among the broken mummies with a crash of bones, rags, and wooden cases, which raised such a dust as kept me motionless for a quarter of an hour."

Belzoni's Discoveries at Aswan and the Pyramids

Ramses II at the Louvre A similar episode occurred while removing an obelisk from the island of Philae near Aswan. "The pier [we had built] appeared quite strong enough...but alas, when the obelisk came gradually on from the sloping bank...the pier...and some of the men, took a slow movement, and majestically descended into the river...For some minutes, I must confess, I remained as stiff as a post." in the end the obelisk was rescued and nobody was seriously hurt." Abu Simbel was covered in sand when Belzoni arrived at the site. He enlisted the help of some British tourist to remove several tons of sand.

To find the burial chamber in the second great pyramid of Giza Belzoni looked for "the spots where the stony matter is not so compact as the surrounding mass; and...the concavity of the pyramid over the place where the entrance might have been expected to be found." Upon locating the right passageway he found his progress blocked by a granite stone. "After thirty days of exertion I had the pleasure of finding myself in the way to the central chamber of one of the two great pyramids of Egypt...my torch, formed of a few candles, gave but faint light." Inside was the sarcophagus of the pharaoh, which had been looted centuries before.

The book Belzoni wrote to describe his adventures was entitled “ Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia; and of a Journey to the Coast of the Red Sea, in Search of the Ancient Berenice; and Another to the Oasis of Jupiter Ammon” . Belzoni died of dysentery while on an expedition on the Benin River in Africa in 1823 at the age of 45.

British Egyptology in the 19th Century

British archaeologists W.M. Flinders Petrie (1853-1942), who did some important work in the 1880s, lived in a tomb in Giza and sometimes emerged at night in his pink long underwear to the horror of tourists that sometimes saw him.

Meira Gold wrote: The growth of British Egyptology between 1822 and 1882 was a direct extension of informal colonial control. In the direct aftermath of the Anglo-French Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), British fieldwork in Egypt focused on diplomatic collecting for the British Museum and topographical surveys by Orientalist expatriates seeking to differentiate between ancient and modern Egyptian cultures. A second phase of fieldwork developed from mid-century whereby experts in Britain relied on colonial networks of collectors and informants in Egypt to communicate field observations over long distances. British Egyptomania and academic Egyptology also grew in tandem as popularizers brought their work to the Victorian public and British tourists flooded into Egypt producing travel accounts. Egyptology was marketed for its ability to shed light on biblical historicity while public exhibitions highlighted the spectacle of the British imperial victories in the East. [Source: Meira Gold, University of New York, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2022]

The Orientalist search for the “Cradle of Western Civilization” in Egypt was closely tied to Victorian science and religion. Egyptology thus allowed for several controversial theories throughout the first three quarters of the century. The most prominent were Victorian pyramidologies that theorized the age, construction, and purpose of the Giza pyramids. Imperial surveyors used scientific instruments to reveal what was believed to be the metrological precision preserved in a variety of Egyptian monuments. These were ambitious projects to recover the lost sciences of ancient “weights and measures” and politically repurpose data towards the legitimization of new national standards in Britain and France that could be linked with the colonization of Oriental territories. The Great Pyramid ( such as, that of 4th Dynasty ruler Khufu) had become a particularly potent symbol since Napoleon’s engineers explored it. In 1837, British military officer Howard Richard Vyse investigated Khufu’s pyramid with civil engineer John Shae Perring. Their infamous use of gunpowder to blast open the structure revealed four new chambers.

Archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie set out for Egypt in 1880 to reassess the claims made by Smyth — a friend of his father, the evangelical engineer William Petrie — through his own trigonometric survey of the pyramids. Traditional “experts” most commonly brought disciplinary perspectives from chronology, philology, biblical exegesis, and classics. During the 1840s and 1850s, philologists moved beyond decipherment to translating and publishing texts. Egyptology became increasingly divisive with renewed debates over historical chronologies, particularly the relative authorities of the Old Testament, classical writers such as Manetho, Herodotus, and Josephus, and Egyptological sources. These arguments were connected to Victorian debates about human antiquity, fueled by new geological and ethnological evidence out of Europe that humans were older than Bishop James Ussher’s creation date of 4004 B.C. Any perceived conflict between archaeology and the Bible within these debates was most accurately over intellectual authority. As with the contemporary evolutionary debates, evangelical British scholars initially resisted the suggestion that Egyptian civilization could be older than 6,000 years.

The British Museum also played a key role in elevating the cultural status of Egyptian antiquities. The arrival in London of booty confiscated from the defeated French catalyzed the museum’s transformation from a cabinet of curiosities into a public-facing institution that fundamentally shaped Egyptological knowledge. The first purpose-built wing, the Townley Gallery, opened in 1808 to showcase the pharaonic “trophies of war”. British audiences were accustomed to regarding Greek and Roman antiquities as aesthetically superior to Egyptian antiquities, which were still considered impressive but odd curiosities. The displays were reorganized in 1823 to accommodate the pieces procured by British consular agents, particularly the bust of Ramses II and Salt’s first collection of sculptures. The British Museum was, moreover, instrumental in standardizing pharaonic history. The chronological focus at mid-century, reflected in the scholarship of John Kenrick, John Gardner Wilkinson (1797– 1875) and Samuel Sharpe (1799–1881) in Britain, and of Karl Richard Lepsius and Emmanuel de Rougé in continental Europe, The arrival at the British Museum of the head of Ramses II, also known as Young Memnon, coincided with the publication of Romantic poet Percy Shelley’s sonnet Ozymandias.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see British Egyptology (1822-1882) by Meira Gold escholarship.org

Golden Age of Egyptology?

Kathleen Sheppard wrote: The period from 1882–1914 has been called the “Golden Age” of Egyptology, but that term is problematic in light of the fact that it was a Golden Age only for Europeans and Americans. In Britain, the founding in 1882 of the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF, now Egypt Exploration Society [EES]) and the beginning of the Great War in 1914 bookend this tumultuous period of Egyptology. [Source: Kathleen Sheppard, Missouri University of Science and Technology, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2021]

During this period, political, religious, economic, and institutional structures impacted the intellectual development of British Egyptology as practiced both in Britain and in Egypt. The establishment of Egyptology as a university-taught subject was crucial to the field. By 1904, the signing of the Entente Cordiale between France and Britain meant that France recognized diplomatically that Britain occupied Egypt. In turn, the French had control over the direction of the Antiquities Service; however, that service was ultimately under the control of the British.

Petrie was very active at this time. In 1882, when he was just 30 years old, he finished measuring and surveying the pyramids of Giza, and had published his book, “The Pyramids and Temples of Giza” in 1883. He is credited with introducing rigorous scientific method to Egyptology and archaeology of ancient Egypt. Petrie soon became known not just for his methodical excavation work, but also for beinginterested in the small finds, like potsherds, small statues, and beads, as opposed to large statues and monuments. Using these smaller pieces others discarded led to one of Petrie’s fundamental contributions to the discipline: using pottery for dating artifacts and establishing a timeline of ancient Egypt. Petrie taught at University College London (UCL). There Margaret Murray is a lot to train archaeologists, who made discoveries. She also was involved in publically unwrapped mummies as she did in front of a large Manchester audience in 1908.

Francis Galton, the founder of eugenics (the endeavor to improve the human species by selective breeding) was interested Petrie’s work and hired him to use his accurate methods to capture and study different racial types portrayed on temple walls all over Egypt. White, British men such Petrie, Galton, and Karl Pearson were driven by the concept that they belonged to a superior culture meant to enlighten and save the rest of world, and also held a number of religious beliefs. The British public held fast to the physical connections to Biblical prophets such as Abraham and Moses that Egypt offered. Bringing artifacts back to London, such as the obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle that stands on the Thames Embankment was one of the ways in which they could strengthen that direct relationship. One minister, the Reverend James King, wrote that the obelisk should be “interesting to the Christian because this same venerable monument was known to Moses and the Children of Israel during their sojourn in the land of Goshen”.

Helen Mary Tirard was one of the honorary secretaries of the EEF when she took a steamer trip up the Nile with her husband in 1888. Their boat, the S.S. Rameses the Great, was one of the largest of Cook’s steamers (such as, a steamship in the fleet of tour company Thomas Cook & Son, established by British mass-tourism entrepreneur Thomas Cook), and it was full for the journey. Sailing out from Cairo, the steamer traveled all the way to the Second Cataract. Tirard would later publish a travelogue from her trip, “Sketches from a Nile Steamer: For Use of Travelers in Egypt (1891)”, in order to excite travelers about ancient Egypt and to help them through the “confused chaos” of Egyptian temples by providing information along the way

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see British Egyptology (1882-1914) by Kathleen Sheppard, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology escholarship.org

German Egyptology

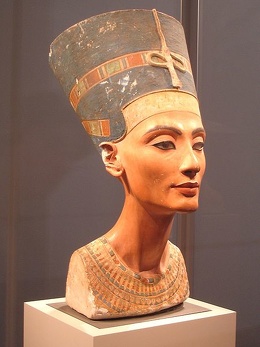

Susanne Voss and Thomas Gertzen wrote: Under Adolf Erman, the successor of Carl Richard Lepsius, one of Egyptology’s “founding fathers,” who had died in 1884, Egyptology experienced the inauguration of the Ancient Egyptian Dictionary Project in 1897 and the founding of the German Oriental Society in 1898. Erman’s successful effort to send Ludwig Borchardt to Egypt in 1895 was the prelude to a permanent presence of German Egyptology in Egypt. The implementation in 1898 of an international project to create the Catalogue Général (CG) was followed by Borchardt’s appointment as scholarly attaché at the German Consulate General in Cairo in 1899, the construction of “German House” in Western Thebes in 1904, the establishment of the Imperial German Institute in Cairo between 1906 and 1907, and the initiation of a program of excavations and research in Egypt. [Source: Susanne Voss and Thomas Gertzen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

In 1912 the painted bust of Queen Nefertiti was discovered. During the same decades, the Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (ZÄS), under Erman’s editorship, remained the single most prestigious journal for matters Egyptological. The far-reaching and long-term influence of the “École de Berlin” (Berlin School), headed by Adolf Erman, is a hallmark of the era.

In the spring of 1906, the increasing appearance of artifacts from Amarna on the Egyptian market attracted Borchardt’s attention. He was able to convince the German Oriental Society (DOG) to excavate at the city of Akhenaten. Since this undertaking was planned as a long-term project, an expedition house was built there in 1908 and a survey grid was laid out for the site to enable its exploration, section by section. The excavation, which lasted from 1911 to 1914, was the first systematic settlement excavation in Egypt. The subsequent discovery of a large number of reliefs and statuary depicting the family of Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten, the foremost of which was the painted bust of Queen Nefertiti in 1912, made headlines worldwide, although stylistically comparable likenesses of the royal family had been discovered and taken to Paris earlier, during nineteenth-century French excavations at Amarna.

In these last years before World War I, German archaeology in Egypt was at its peak. Since 1904, permanent quarters had existed in Egypt — the “German House” at Western Thebes, which continued to serve primarily as a guest-house for the scholars involved in the dictionary project. In 1906–1907 Borchardt’s attaché post, the German House, and the attaché’s library and photo collection were consolidated to form the Kaiserlich Deutsches Institut für ägyptische Altertumskunde in Kairo (the Imperial German Institute in Cairo). In addition to the German archaeological efforts sponsored by the DOG, new insights and finds resulted from, for example, Georg Steindorff’s work at Giza and in Nubia and Otto Rubensohn’s excavations in Middle and Upper Egypt on behalf of the Papyruskartell. Beginning in 1903, Wilhelm Pelizäus sponsored Steindorff’s Giza excavations, setting a precedent for the engagement of private collectors in archaeological activity in Egypt, which museums in Germany later adopted. Germany’s industrious fieldwork notwithstanding, archaeological methodology played a minor role in the study of Egyptology at German universities.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see German Egyptology (1882-1914) by Susanne Voss and Thomas Gertzen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology escholarship.org

Harry Burton — Great Photographer of Ancient Egypt

In 1914, Harry Burton (1879–1940) was hired as a member of the graphic section, initially to photograph tomb interiors and later to record the work of the Museum's excavation team. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art “Burton rapidly gained a reputation as the finest archaeological photographer of his time. Thus, when Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, he promptly asked the Metropolitan for the loan of Burton's services. For the next eight years, Burton divided his time between Tutankhamun and the Egyptian Expedition. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig, Department of Egyptian Art and Malcolm Daniel Department of Photographs, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum. org \^/]

Between 1914 and his death in 1940, Burton produced and printed more than 14,000 glass negatives; the majority of those negatives and prints are in the archives of the Department of Egyptian Art. To Egyptologists, Harry Burton's photographs are among the great treasures of the department. For the art historian, he has left a complete photographic record of dozens of decorated tombs as they were preserved in the early twentieth century. For the archaeologist and the historian, he has left an invaluable record of the Museum's excavations. Since archaeology is a process of removal and destruction, Burton's stage-by-stage documentation of work in progress allows us to re-create the context of objects that are now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and in New York. Burton's photographs of the tomb of Tutankhamun, much better known than his work for the Museum, give the same thorough record of each new discovery within that tomb.

Far more than dry scientific records, Burton's photographs also inspire a sense of wonder because of his ability to tell a story — to convey the atmosphere of a tomb unopened for more than three millennia, the poignancy of a floral offering left at the foot of a coffin, or the anticipation of an excavator confronted by a sealed door. Burton was a superb archaeological photographer with a knack for producing clear and informative photographs under the most difficult circumstances. In carrying out his documentary mission, he often set up his camera and lights with a sense of artistry as well as practicality and created pictures we find beautiful, exciting, or mysterious. The modern viewer may also find unintended associations in his work. Just as we might admire an ancient alabaster vase in part because its design seems "so modern," some of Burton's pictures remind us of photographs made in the seventy or eighty years that followed. That connection is not altogether accidental. Many artists from the 1920s to the present have tried to apprehend the world by using their cameras to gather and classify an archive of faces, natural forms, or manmade constructions — to examine our own civilization as a future archaeologist might, borrowing from photographers like Burton the strategies of exhaustive documentation and deadpan presentation.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Harry Burton (1879–1940): The Pharaoh’s Photographer” from the Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024