Home | Category: Desert Animals

ARABIAN ORYX

Arabian oryxes (Oryx leucoryx) are also called or white oryxes. Native to the deserts and steppe areas of the Arabian Peninsula and the smallest member of the genus Oryx, they are medium-sized antelope and bovids with a distinctive shoulder bump, long, straight horns, and a tufted tail. The Arabian oryx was extinct in the wild by the early 1970s, but was saved in zoos and private reserves, and was reintroduced into the wild starting in 1980. [Source: Wikipedia

In 1986, Arabian oryxes were reclassified as endangered rather than extinct in the wild on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List after their reintroduction into the wild was deemed successful, meaning that their population was of significant size and reproducing. In 2011, the Arabian oryx became the first animal to revert to vulnerable status after previously being listed as extinct in the wild. In 2016, populations were estimated at 1,220 individuals in the wild, including 850 mature individuals, and 6,000–7,000 in captivity worldwide.

Arabian oryx were originally found in Syria, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Sinai, and the Arabian Peninsula but are restricted to Oman, Jordan, Israel and the Arabian Peninsula where they have been reintroduced. Usually they are found in arid plains and deserts, but have been observed on rocky hillsides and in thick brush. Their habitat according to Nowak (1999) consists of "flat and undulating gravel plains intersected by shallow wadis and depressions and the dunes edging sand deserts with a diverse vegetation of trees, shrubs, and grasses." Much of the vegetation is in form of stands of dense, spiny shrubs with tough (hard or waxy) evergreen leaves. [Source: Heather Leu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Arabian Oryx Characteristics and Diet

Arabian oryx range in weight from 100 to 210 kilograms (220 to 462 pounds). Their head and body length varies from 1.53 to 2 meters (5 to 6.6 feet) and they stands between 0.79 and 1.25 meters (2.6 and 4.1 feet) tall at the shoulder. Their tail is 45 to 90 centimeters (17.7 to 35 inches), Their average lifespan in captivity is 20.8 years. [Source: Heather Leu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\; Wikipedia]

The coat of Arabian oryxes is almost luminous white, hence their other common name, white oryx. Their undersides and legs are brown. Black stripes occur where the head meets the neck, on the forehead, on the nose, and going from the horn down across the eye to the mouth. A mane extends from the head to the shoulders and the tail is tufted. Males also have a tuft of hair on the throat. Young are shades of brown and have markings only on their tails and knees. /=\

Both sexes have long, ringed horns which are 0.6–1.5 meters (2–4.9 feet) long. They are fairly straight and are directed backwards from the eyes. The horns of females are usually longer and thinner than the horns of males.

Arabian oryxes are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts). Their diet consists mainly of grasses, but they eat a large variety of vegetation, including buds, herbs, fruit, tubers and roots. They can feed on diverse types of grasses and shrubs — whatever is found in their arid habitat. Herds of follow infrequent rains to eat the new plants that grow afterwards. Arabian oryxes go to streams and water holes to drink. They can go for several weeks without water. When free water is not available, they can obtain moisture from sources such as melons and succulent bulbs. In Oman, Arabian oryx primarily eat grasses of the genus Stipagrostis, flowers from Stipagrostis plants appeared highest in crude protein and water, while leaves seemed a better food source with other vegetation.

Bovids

Oryx are bovids. Bovids (Bovidae) are the largest of 10 extant families within Artiodactyla, consisting of more than 140 extant and 300 extinct species. According to Animal Diversity Web: Designation of subfamilies within Bovidae has been controversial and many experts disagree about whether Bovidae is monophyletic (group of organisms that evolved from a single common ancestor) or not. [Source: Whitney Gomez; Tamatha A. Patterson; Jonathon Swinton; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Wild bovids can be found throughout Africa, much of Europe, Asia, and North America and characteristically inhabit grasslands. Their dentition, unguligrade limb morphology, and gastrointestinal specialization likely evolved as a result of their grazing lifestyle. All bovids have four-chambered, ruminating stomachs and at least one pair of horns, which are generally present on both sexes.

Bovid lifespans are highly variable. Some domesticated species have an average lifespan of 10 years with males living up to 28 years and females living up to 22 years. For example, domesticated goats can live up to 17 years but have an average lifespan of 12 years. Most wild bovids live between 10 and 15 years, with larger species tending to live longer. For instance, American bison can live for up to 25 years and gaur up to 30 years. In polygynous species, males often have a shorter lifespan than females. This is likely due to male-male competition and the solitary nature of sexually-dimorphic males resulting in increased vulnerability to predation. /=\

See Separate Article: BOVIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBFAMILIES factsanddetails.com

Ruminants

Cattle, sheep, goats, yaks, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread.

As ruminants evolved they rose up on their toes and developed long legs. Their side toes shrunk while their central toes strengthened and the nails developed into hooves, which are extremely durable and excellent shock absorbers.

Ruminants helped grasslands remain as grasslands and thus kept themselves adequately suppled with food. Grasses can withstand the heavy trampling of ruminants while young tree seedlings can not. The changing rain conditions of many grasslands has meant that the grass sprouts seasonally in different places and animals often make long journeys to find pastures. The ruminants hooves and large size allows them to make the journeys.

Describing a descendant of the first ruminates, David Attenborough wrote: deer move through the forest browsing in an unhurried confident way. In contrast the chevrotain feed quickly, collecting fallen fruit and leaves from low bushes and digest them immediately. They then retire to a secluded hiding place and then use a technique that, it seems, they were the first to pioneer. They ruminate. Clumps of their hastly gathered meals are retrieved from a front compartment in their stomach where they had been stored and brought back up the throat to be given a second more intensive chewing with the back teeth. With that done, the chevrotain swallows the lump again. This time it continues through the first chamber of the stomach and into a second where it is fermented into a broth. It is a technique that today is used by many species of grazing mammals.

See Ruminants Under MAMMALS factsanddetails.com

Arabian Oryx Behavior and Reproduction

Arabian oryx are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), solitary, social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups) and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. [Source: Heather Leu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Oryx are gregarious. Their normal group size is 10 animals or fewer, but as many as 100 individuals have been observed in one herd. Captive Arabian oryx herds have consisted of a single dominant adult male and several adult females and young. Other males form bachelor groups that have a hierarchy established through fighting and chases. /=\

Oryx have been described as alert, wary, and keen sighted. They defend themselves by lowering their head so that their sharp horns point forward. Arabian oryx are active mainly at night. During the day they spend much of their time in the shade of acacia trees. An introduced herd of Arabian oryx in Jordan was observed being active just after dawn, they grazed until about 10:00pm, rested from 2:00pm to 3:00pm , grazed again, then began to move toward a sleeping area around sunset.

When Arabian oryx are not eating or moving about, they dig shallow depressions in the soft ground under shrubs and trees for resting. They are able to detect rainfall from a great distance and move in the direction of fresh plant growth. Since rainfall is irregular they often travel over hundreds of square kilometers in no set pattern. An introduced herd of Arabian oryx in Oman was reported, in 1983, to use a range of about 3,000 square kilometers, with suitable areas about to inhabit of 100 to 300 square kilometers. These were were occupied for 1 to 18 months at a time. The population density was 0.35per square kilometers. By 1993, the occupied area of Oman had grown to 14,121 square kilometers and contained 18 breeding herds, with a mean size of 5.8 individuals and a mean range of 57 square kilometers. In addition, there were 10 solitary bulls with largely separate territories of 44-453 square kilometers and a small bachelor herd. /=\

The breeding season of Arabian oryx varies. In favorable conditions, a female can produce a calf once a year during any month. Most births among introduced herds in Oman and Jordan occur from October to May. The average gestation period is eight months. The number of offspring is usually one. The age in which young are weaned is around 4.5 months. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. Young are weaned by 4.5 months, Captive females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age 2.5 to 3.5 years.

Arabian Oryx, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Arabian oryx are listed as Vulnerable. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. [Source: Heather Leu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\; Wikipedia]

Arabian oryx have traditionally greatly valued by humans. Their meat was eaten. Their hides were used for leather. Other parts of their body were used in medicines. The head and horns were valued by a trophy hunters.

The last known individuals in the wild were killed in 1972, though there were unconfirmed reports that they still existed as late as 1979. Conservation efforts began in the 1950s efforts when several Arabian countries established captive herds. In 1962, some Arabian oryx were taken from the wild and were brought to the U.S. These animals formed the heart of a major an international breeding effort.

Arabian oryx were reintroduced into the wild in Oman in 1982, Jordan in 1983, and central Saudi Arabia in 1990. In 2020, the IUCN estimated there were more than 1,200 Arabian oryx in the wild and 6,000 to 7,000 in captivity worldwide in zoos, preserves, and private collections. Some of these are in large, fenced enclosures in Syria (Al Talila), Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE. The Phoenix and San Diego zoos have relatively large herds. In 2007. Oman's Arabian Oryx Sanctuary became the first site ever to be removed from the UNESCO World Heritage List. This was done because the Omani government opened 90 percent of the site to oil prospecting. As a result, the Arabian oryx population there fell from 450 in 1996 to 65 in 2007. By the 2010s fewer than four breeding pairs were left on the site.

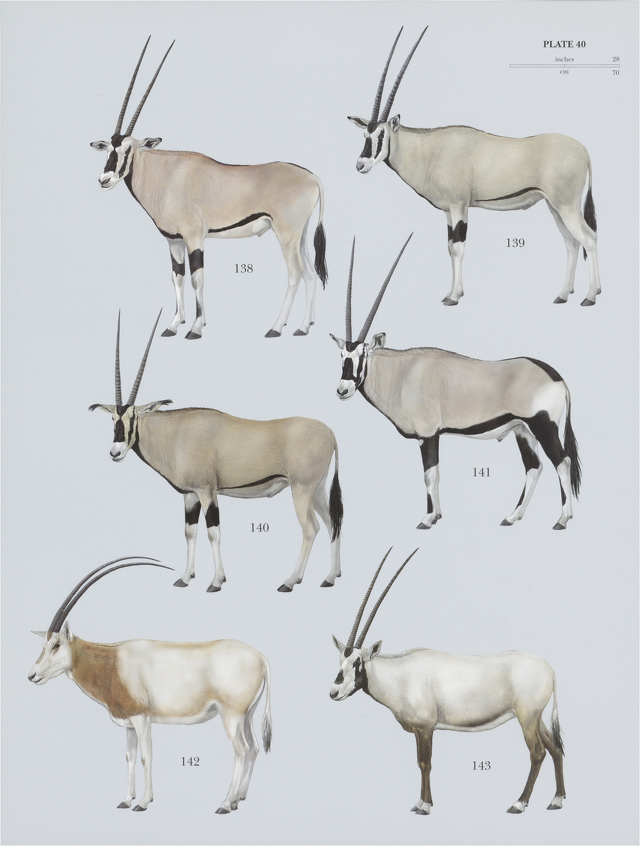

Oryx species: 138) Beisa Oryx (Oryx beisa), 139) Galla Oryx (Oryx gallarum), 140) Fringe-eared Oryx (Oryx callotis), 141) Gemsbok (Oryx gazella), 142) Scimitar-horned Oryx (Oryx dammah), 143) Arabian Oryx (Oryx leucoryx)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025