Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

THIRD INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (1070–712 B.C.)

Golden Mask of Psusennes I

After 1085 B.C. Egypt was divided and ruled by priests. Egyptian culture went into a period of decline. Treasuries shrunk as a result of expensive monument building and military campaigns. There were food riots and strikes. In 525 B.C., Egypt was conquered the Persians The New Kingdom was followed by the Third Intermediate Period (1075 to 715 B.C.), the Late Period (715 to 332B.C.) and the Greco-Roman Period (332 B.C. to A.D. 395). During this time the capital of Ancient Egypt moved from Tanis to Thebes to Salis to Leontopolis to Hermoplois to Herakleopolis to Thebes.

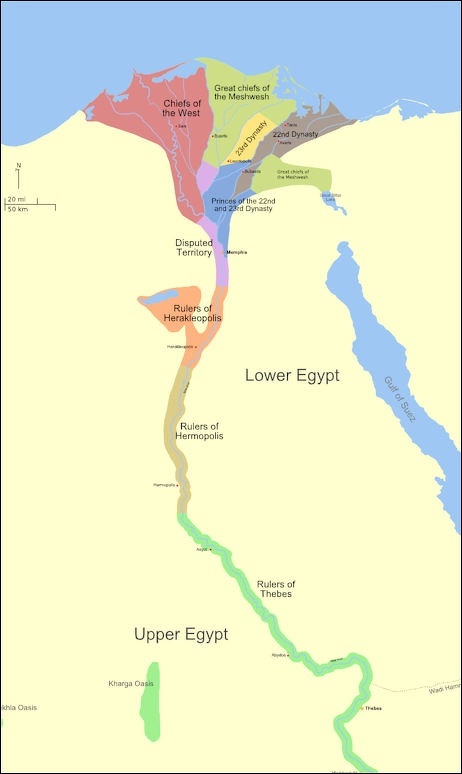

Third Intermediate Period (1075 to 715 B.C.) included the 21st. 22nd , 23rd, and 24th dynasties, with 35 rulers and long periods of rule by the Libyans and Nubians. The pharaohs of the 22nd and 23rd dynasties were mostly Libyans. Those of the brief 24th were Egyptians of the Nile Delta, and those of the 25th were Nubians and Ethiopians. "Intermediate" is used to describe periods when there was no strong centralized government unifying the Upper and Lower Egypt. According to Live Science: The central government was sometimes weak during the Third Intermediate Period and the country was not always united. During this time cities and civilizations across the Middle East had been destroyed by people from the Aegean, whom modern-day scholars sometimes call the "Sea Peoples." While Egyptian rulers claimed to have defeated the Sea Peoples in battle, it didn't prevent Egyptian civilization from collapsing. The loss of trade routes and revenue may have played a role in the weakening of Egypt's central government. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

At the end of the 20th Dynasty a division takes place between the Theban king-priests, starting with Herihor, and the new dynasty founded by Smendes was established at Tanis. During this — the 21st — Dynasty the priests of Amun at Thebes styled themselves as kings and governed southern Egypt from around 1075–945 B.C. In the north, families originally of Libyan descent founded Dynasty 22 (around 945–715 B.C.), ruling from the Delta.

James Allen and Marsha Hill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “At the death of Ramesses XI, the throne passed to Smendes, a northern relative of the High Priest of Amun. Smendes' reign (ca. 1070–1044 B.C.) initiated some 350 years of politically divided rule and diffused power, known as the Third Intermediate Period. The Third Intermediate Period laid the foundation for many changes that are observable in art and culture throughout the first millennium. Though its details are still not fully clear, this period of Egyptian history can be divided into three general stages. During the first of these, Dynasty 21 (ca. 1070–945 B.C.), Egypt was governed by pharaohs ruling from Tanis in the eastern Delta and by the High Priests of Amun ruling from Thebes. Relations between the two centers of power were generally good. [Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org\^/; [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

“Preoccupied with internal rivalries during the Third Intermediate Period, Egypt gradually lost its traditional control of Nubia, located to its south. About 760 B.C., an independent native dynasty began to rule Nubia, or Kush, from Napata in what is now the Sudan and extended its influence into southern Egypt. In 729 B.C., the Egyptian rulers Namlot and Tefnakht joined forces to extend their control farther into Upper Egypt. The Nubian king Piankhy perceived this as a threat to his independence and moved against the Egyptian coalition. His invasion proved successful, and the various Egyptian rulers submitted to his leadership at Memphis in 728 B.C. This event marked the inception of seventy-five years of Nubian rule in Egypt.” \^/

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt, 1100-650BC” by Kenneth Kitchen (1996) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“Poisoned Legacy: The Fall of the Nineteenth Egyptian Dynasty” by Aidan Dodson (2016) Amazon.com;

”Rameses III, King of Egypt: His Life and Afterlife” by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Collapse of the Bronze Age: The Story of Greece, Troy, Israel, Egypt, and the Peoples of the Sea” by Manuel Robbins (2001) Amazon.com;

“Inscriptions from Egypt's Third Intermediate Period” by Robert Kriech Ritner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Egypt in the Third Intermediate Period”

by James Edward Bennett (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Excavations at Mut al-Kharab II: The Third Intermediate Period in the Western Desert of Egypt” by Richard J. Long Amazon.com;

“The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 BC)” by B. Bothmer, Emma Swan-Hall (1973) Amazon.com;

“Women, Gender and Identity in Third Intermediate Period Egypt: The Theban Case Study” by Jean Li (2017) Amazon.com;

“Egypt of the Saite Pharaohs, 664–525 BC” by Roger Forshaw (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2011, 2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2017) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” (DK Eyewitness Books) by George Hart (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

Tanis

pendant

Located in northeastern part of the Nile Delta, Tanis was the capital of Egypt's 21st and 22nd Dynasties and was a wealthy commercial center in northern Egypt long before the rise of Alexandria. According to National Geographic History: The riches uncovered from the ancient city include a royal tomb complex filled with golden masks, jewelry, silver coffins, and other treasures rivaling those of King Tut. And yet, few people have heard about this spectacular archaeological site. Readers of the Old Testament may know it as Zoan, where Moses was said to work miracles. Today it is called Sân el-Hagar, a small, otherwise uneventful, town. [Source: Pat Daniels, National Geographic, December 28, 2022]

Tanis, in the Nile Delta northeast of Cairo, was capital of the 21st and 22nd dynasties, during the reign of the Tanite kings in Egypt's Third Intermediate period. The city's advantageous location enabled it to become a wealthy commercial center long before the rise of Alexandria. But political fortunes shifted, and so did the river's waters—and in recent centuries the Tanis site had became a silted plain with some hill-like mounds thought to be of little interest. [Source Brian Handwerk, National Geographic History]

Egypt's "intermediate periods" were times of weak central government when power was divided and sometimes passed out of Egyptian hands. During this time the rulers of Tanis were of Libyan decent, not scions of traditional Egyptian families. That distinction may have contributed to the city's disappearance in later years.

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: The creation of Tanis — the Egyptian “Djanet”, on the Pelusiac branch of the Nile — is the most striking event of the early Intermediate Period. “From its beginning Tanis was conceived of as a northern replica of Thebes, where, in addition to Amun, Mut and Khonsu were venerated. The Mut temple, south of the precinct of Amun, is definitively dated to the Third Intermediate Period: foundation deposits with the name of Siamun have been discovered at the entrance gate. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Later Tanis disappeared with the shifting course of the Nile river. According to National Geographic Spectacular finds came in 1939, when French archaeologist Pierre Montet uncovered a royal tomb complex that included three intact and undisturbed burial chambers. Sadly, World War II intervened and eclipsed his discoveries. Though some of Tanis’s treasures can now be found in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum, and a sacred lake dedicated to the goddess Mut was located in 2009, scientists know there is more to be discovered. Infrared satellite imagery reveals more buildings waiting to be uncovered.

The Discovery of Tanis See GREAT DISCOVERIES IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY africame.factsanddetails.com

Discoveries in Tanis

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: The creation of Tanis — the Egyptian “Djanet”, on the Pelusiac branch of the Nile — is the most striking event of the early Intermediate Period. In the northern part of the site, a vast temenos was surrounded by an enormous mudbrick wall, on which stamps of the cartouche of Psusennes I have been found. Psusennes I had constructed there a temple of Amun-Ra “Lord of the Throne of the Two Lands,” of which the foundation deposits have been found, but which has subsequently been remodeled and enlarged to such an extent that it is impossible to say what the original building looked like. The mudbrick enclosure wall also included the area where had been established the tombs of the kings and members of the royal families of both the 21st and 22nd dynasties (Smendes, Psusennes I, Ramses-Ankhefenmut, Undebaundjed, Amenemope, Osorkon I, Siamun, Psusennes II, Osorkon II, Takelot I, Shoshenq II, Hornakht, Takelot II, Shoshenq III). [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

The tombs were polytaphs, containing a number of burials, and after various changes served as royal cachettes. This radical innovation was probably instigated by the layout of the site of Tanis itself: a sandy tell in the midst of agricultural land, far removed from the “gebel” — the mountains that form the natural boundary of the Nile valley, where for centuries the tombs of the pharaohs and the elite were chiseled out. The tradition of royal burial within the temenos walls continued at Sais by the rulers of the 26th Dynasty, whose tombs unfortunately have been plundered, and at Mendes, in the burial chamber of Nepherites I. The sarcophagus of Nectanebo II, reused and finally found at Alexandria, may have originally been part of a burial in Memphis.

A temple dedicated to Khonsu may have been built at that time north of the Amun temple, later to be rebuilt during the 30th Dynasty, as demonstrated by the discovery of statues of the god in the form of a baboon, with cartouches of Psusennes I. During the 21st Dynasty, a temple dedicated to Amun of Ipet, discovered as recently as the end of the twentieth century, was built on the southern part of the tell, modeling the one in Luxor. Building activities of the kings of the 21st Dynasty are rarely encountered in other parts of Egypt. The few examples are the temple of Isis at Giza and, at Memphis, a chapel with the name of Siamun.

Art and Culture During the Third Intermediate Period

James Allen and Marsha Hill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “With the weakening of centralized royal authority in the Third Intermediate Period, the temple network emerged as a dominant sphere for political aspirations, social identification, and artistic production. The importance of the temple sphere obtained, with more or less visibility, for the ensuing first millennium.[Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

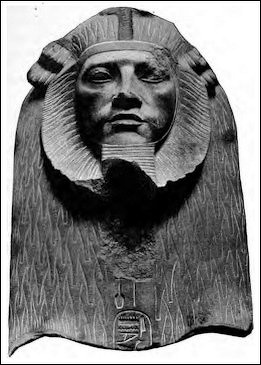

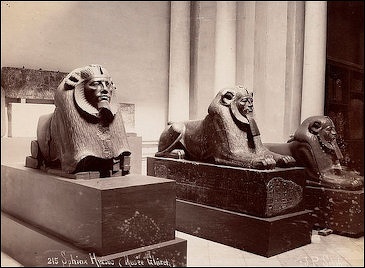

Amenemhat sphinx

“Relatively little building took place during the Third Intermediate Period, but the creation of stylistically and technologically innovative bronze and precious temple statuary of gods, kings, and great temple officials flourished. Temple precincts, with the sanctity and safety they offered, were favored burial sites for royal and nonroyal persons alike. Gold and silver royal burial equipment from Tanis shows the highest quality of craftsmanship. Nonroyal coffins and papyri bear elaborate scenes and texts that ensured the rebirth of the deceased. \^/

“New emphasis was placed on the king as the child/son of a divine pair. This theme and other royal themes are expressed on a series of delicate relief-decorated vessels and other small objects chiefly in faience, but also of precious metal. The same theme is manifested architecturally in the emergence and development through the first millennium of the mammisi, or birth house, a subordinate temple where the birth of a juvenile god identified with the sun god and the king was celebrated.” \^/

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: “During the 22nd Dynasty Shoshenq I erected a temple to Amun- Ra “Great of Fame, Lord of the Promontory” at el-Hiba/Teudjoi. At Karnak he built the Bubastide gate and a double colonnade along the court in front of the second pylon. On the southern portico an inscription of the “Annals of Osorkon” can be found, which has been dated to years 11 and 12 of Takelot I . Osorkon II was a prolific builder, of whose constructions we find remains in Upper as well as Lower Egypt. Planning to be buried at Tanis, he considerably enlarged the main temple, where the second and third pylons are attributed to his reign. These gateways, their entrances conspicuously flanked by pairs of obelisks, are impressive even today. Columns from the Old Kingdom, already reused by Ramses II (probably at Pi- Ramesse, the present-day Qantir), were transported to Tanis, where Osorkon II usurped them by inscribing his name. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Moreover, they have been found outside the temple complex of Amun-Ra there, where they had again been reused, perhaps during the 30th Dynasty, in what is now a dilapidated ruin known as the “East Temple”. Shoshenq III added to the temple complex, particularly by building a monumental access gate at the west side, which remained functional for the duration of the temple’s use. In addition, we know that Shoshenq V built a temple, subsequently dismantled. Building stones bearing his name have been found reused in the construction of the sacred lake of the 30th Dynasty. The temple of Bubastis benefited from important additions by Osorkon II, who had a special connection to the goddess Bastet, “Lady of Bubastis”: a monumental gate was erected, decorated with sed-festival scenes that present details not attested elsewhere.

“A practice characteristic of the Third Intermediate Period was to erect “donation stelae,” which guaranteed the temple donations specified upon them. These stelae have very specific formulations and a unique iconography. They are particularly numerous during the 21st and 22nd dynasties and have also been attested for the 26th (Saite) Dynasty, but become increasingly rare after that period. The donation formulae clearly show that private individuals with links to the temple, such as gate-keepers, would receive a plot of land from the king (or from a great chief of the Meshwesh during the Libyan Period) through an intermediary official. The recipient would have the right to work the land in exchange for payment of part of the harvest to the temple. This well- recorded system gives important information on the administrative and economic function of temples at this time.

“The period of the Libyan anarchy has left scant architectural remains. Best known are the tombs of military and religious dignitaries: in Memphis, the tomb of prince Shoshenq, son of Osorkon II and high priest of Ptah; and at Herakleopolis, the tombs of several great chiefs of the Ma .

List of Rulers from the Third Intermediate Period

Third Intermediate Period

(ca.1070–713 B.C.)

Dynasty 21, (ca. 1070–945 B.C.)

Smendes (ca. 1070–1044 B.C.)

HP Painedjem I (ca. 1070–1032 B.C.)

HP Masaharta (ca. 1054–1046 B.C.)

HP Djedkhonsefankh (ca. 1046–1045 B.C.)

HP Menkheperre (ca. 1045–992 B.C.)

Amenemnisu (ca. 1044–1040 B.C.)

Psusennes I (ca. 1040–992 B.C.)

Amenemope (ca. 993–984 B.C.)

HP Smendes (ca. 992–990 B.C.)

HP Painedjem II (ca. 990–969 B.C.)

Osochor (ca. 984–978 B.C.)

Siamun (ca. 978–959 B.C.)

HP Psusennes (ca. 969–959 B.C.)

Psusennes II (ca. 959–945 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 22 (Libyan), (ca. 945–712 B.C.)

Sheshonq I (ca. 945–924 B.C.)

Osorkon I (ca. 924–889 B.C.)

Sheshonq II (ca. 890 B.C.)

Takelot I (ca. 889–874 B.C.)

Osorkon II (ca. 874–850 B.C.)

Harsiese (ca. 865 B.C.)

Takelot II (ca. 850–825 B.C.)

Sheshonq III (ca. 825–773 B.C.)

Pami (ca. 773–767 B.C.)

Sheshonq V (ca. 767–730 B.C.)

Osorkon IV (ca. 730–712 B.C.)

Dynasty 23, (ca. 818–713 B.C.)

Pedubaste I (ca. 818–793 B.C.)

Iuput I (ca. 800 B.C.)

Sheshonq IV (ca. 793–787 B.C.)

Osorkon III (ca. 787–759 B.C.)

Takelot III (ca. 764–757 B.C.)

Rudamun (ca. 757–754 B.C.)

Iuput II (ca. 754–712 B.C.)

Peftjaubast (ca. 740–725 B.C.)

Namlot (ca. 740 B.C.)

Thutemhat (ca. 720 B.C.)

Dynasty 24, (ca. 724–712 B.C.)

Tefnakht (ca. 724–717 B.C.)

Bakenrenef (ca. 717–712 B.C.)

Twenty First Dynasty 1069 – 945 B.C.

The power and control center of Egypt moved from Upper Egypt to Lower Egypt after the founding of cities in the eastern Nile Delta by kings in the later 19th and 20th Dynasties. The completion of the division of Egypt initiated the beginning of the 21st Dynasty and the Third Intermediate Period and the end of the New Kingdom. Smendes proclaimed himself king after Ramses XI’s death and ruled from Tanis in the Nile Delta. The country was eventually divided between the kings and the high priests of Amun at Thebes. The leaders of the 21st Dynasty were: Smendes 1069-1043 B.C.; Amenemnesu 1043-1039 B.C.; Psusennes I 1039-991 B.C.; Amenernipet 993-984 B.C.; Osorkon 984-978 B.C.; Siamun 978-959 B.C.; Psusennes II 959-945 B.C.. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Live Science reported: In 1939, archaeologist Pierre Montet discovered the tomb of Psusennes I, His burial chamber was located in Tanis on the Nile Delta. The pharaoh was buried in a coffin made of silver and was laid to rest wearing a spectacular gold burial mask, Montet found. (Psusennes I is sometimes called the "Silver King" because of his silver coffin. ) Because of the delta's humidity, some of the grave goods did not survive; however, canopic jars (used to store some of the pharaoh's organs) and shabti figurines (meant to serve the king in the afterlife) were also discovered. Because the tomb was discovered when the Second World War was starting, it received little media attention. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 26, 2016]

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “Around 1070 B.C., Egypt was in decline, losing its Nubian provinces and other sources of revenue. A new royal family began to rule from Tanis in the far north-east, but the south was ruled by a largely independent series of High Priests at Thebes. Amenemopet was one of the Tanite kings of the 21st Dynasty. His mummy was found in the tomb of his predecessor, Psusennes I, at Tanis in 1939, adorned with the gold mask illustrated above. Although superficially impressive, the gold is very thin, only covering the front of the head, in contrast with the thick helmet-mask of the 18th-Dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Smendes died in 1043 B.C. and the brief interlude before the accession of Pseusennes I in 1039 B.C. was filled by Amenemnisu, a son of Herihor and Nodimet. Civil war still raged in the Theban area, and a number of the dissidents were exiled to the western oases, then held by Libyan chiefs. A black granite stele in the Louvre records the banishment of these people. Strangely, they were subsequently permitted to return under an octancular decree from Amun. It all seems to be part of a plan between the North and South, the secular and the religious fractions. This rapprochement was set in motion by the next king, Psusemes I, in allowing the marriage of his daughter Isiemkleb to the High Priest Menkheperre. “Between the reigns of Amenemope and Siamun there seems to have been a ruler called Aakheperie Setepenre, usually referred to as Osorkon the Elder, who may have reigned for up to 6 years, but the evidence is scanty. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Siamun who came to the throne in about 978 B.C. reigned for almost 20 years. He is chiefly represented by his extensive building work in the Delta, at Piramesse, but principally at Tanis where he enlarged the temple of Amun. His name, however, is also very prevalent at Thebes, where it occurs several times with different regional years on the bandages used in the rewrapping of a number of the later royal mummies from the Bier-el-Bahari cache of 1881(DB 320). +\

Biblical Accounts Related to the 21st Dynasty

Shepherd kings

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The little light that is thrown on the 21st Dynasty comes largely from the biblical record, since the period coincides with the struggle of David in Israel to unite the tribes and destroy the Philistines, exemplified initially in the story of David and Goliath. Siamun obviously kept a watching brief on the near Eastern situation and Egypt was able to interfere from time to time to protect her own interests and trade routes. +\ [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“There evidently was a change in the Egyptian view of marriages. There had been a steady stream of foreign princesses coming to the Egyptian court but the process was slightly reversed, with Egyptian princesses marrying out: one princess married Sadal, the crown prince of the Kingdom of Edom, when he took refuge in Egypt after succumbing to David's attacks. +\

“An Egyptian campaign in which Gezer was seized from the weakened Philistines is recorded in the Old Testament. Solomon had succeeded his father David and an Egyptian alliance was sealed by Solomon's marriage to an Egyptian princess. The end of the Dynasty came with Psusenness II, whose reign lasted 14 years, is little known. His successor Sheshong I, the founder of the 22nd Dynasty married Maarkare, Psusenne's daughter, thus forging another dynastic marriage tie.” +\

Twenty-Second Dynasty (945 – 715 B.C.)

After the shortlived 21st Dynasty, the 22nd Dynasty, of Libyan origin, came to power in Egypt. Shoshenk (Shishak of the Bible) reunited Egypt. Egypt was ruled for roughly 200 years by kings of Libyan origin during the 22nd Dynasty. The 22nd Dynasty kings were: Shoshenk I 945-924 B.C.; Osorkon I 924-889 B.C.; Shoshenk II 890 B.C.; Takelot I 889-874 B.C.; Osorkon II 874-850 B.C.; Takelot II 850-825 B.C.; Shoshenk III 825-773 B.C.; Pimay 773-767 B.C.; Shoshenk V 767-730 B.C.; Osorkon IV 730-715 B.C.”[Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Following the death of Solomon of Israel, Shoshenk attacked Jerusalem, defeating the kingdom of Judah (Israel) before being stopped at Megiddo, the site of Thutmose III’s victories 500 years before. Shoshenk had given refuge to the Israelite pretender Jeroboam and, after the latter had returned to Israel, invaded first Judah, thoroughly ravaging and looting the country, and then Israel, treating it in like manner. Returning with vast plunder, and leaving a weakened Palestine behind him, Sheshonk retired to Egypt. Henceforth the Libyan rulers of Egypt, having shown their power, left West Asia alone. Shoshenk is mentioned in 1 Kings 14:25–26 and 2 Chr. 12:2–9. His successors tried to appease Thebes and Upper Egypt but tensions remained, and in the 9th and early 8th centuries B.C., as many as four kings claimed to rule Egypt at once. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003; Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

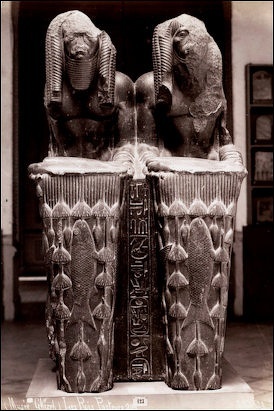

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “Libyans had settled in Egypt from the 18th Dynasty onwards, and became well established in the north-west, with their own traditional leaders or chieftains. Some of these leaders married into Egyptian ruling families, and finally, around 975 B.C., a member of one of these Libyo-Egyptian families became pharaoh. |Bearing such Libyan names as Shoshenq, Osorkon and Takelot, a series of these Libyo-Egyptian kings comprised the 22nd and 23rd dynasties. Initially, major efforts were made to restore Egypt's internal unity and international standing, and Shoshenq I undertook military campaigns into Palestine. Osorkon I, whose statue, shown above, can be seen in the Louvre Museum in Paris, was engaged in diplomatic efforts in the same area. However, internal conflicts developed once more, and by 840 B.C. the country was irrevocably split in two.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“The second stage began in 945 B.C., when the throne passed to a powerful family of Libyan descent, ruling in the eastern Delta. Egypt's erstwhile western enemies now became its rulers for the next two centuries (Dynasty 22, ca. 945–712 B.C.). Despite their Libyan origin, these pharaohs ruled as native Egyptians. The first of them, Sheshonq I (ca. 945–924 B.C.), is the most important. He appears in the Bible under the name Shishak, the Egyptian ruler who sacked Jerusalem in Year 5 of the reign of Solomon's son, Rehoboam. [Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org\^/]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: The 22nd Dynasty is often referred to as the Libyan Bubastite Dynasty. Manetho lists the kings of this Dynasty as being from Bubastis which is located in the eastern delta. The Libyan element is evident in the founder, Sheshonq I, who inaugurated the sequence of Libyan Chiefs which ruled Egypt for the next 200 years. Sheshonq himself allied by marriage as the son-in-law of his predecessor Pseusennes II, had the strength of the military behind him as the commander-in-chief of all the armies of Egypt. Sheshonq was a strong ruler who brought the divided factions of Thebes and Tanis together into a once more united Egypt.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Twenty-Second Dynasty of Egypt and The Bible

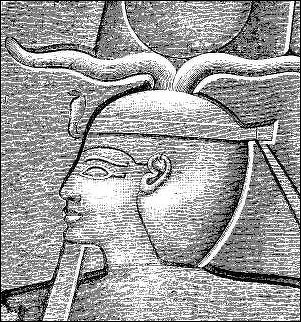

Shoshenq I

Shoshenq I, a Lybian referred to in the Bible as King Shishak, was a military man who unified Egypt at the time there were two power centers, one in Tanis and one in Thebes. He then turned his attention to Palestine. King Solomon had just died, and Judea and Israel were feuding. Hoping to gain control of trade routes held by Egypt in the New Kingdom, Shoshenq I invaded Palestine. One army came in from the south and another came down from north, A number of towns were defeated and Jerusalem was forced to pay tribute but in the end Shosheng retreated and died soon after his return to Egypt.

Following the death of Solomon of Israel, Shoshenk attacked Jerusalem, defeating the kingdom of Judah (Israel) before being stopped at Megiddo, After Solomon, the Hebrew kingdom of Judah was ruled his son Rehoboam, who proved to be a more brutal leader than his father. There was a revolt against the House of David around 930 B.C. and the Hebrew kingdom divided into two kingdoms: the southern kingdom of Judah in the south with Jerusalem as the capital and Rehoboam as the ruler; and another kingdom in the north with Samaria as the capital.

Following the death of Rehoboam the kingdom of Judah was ruled by Jeroboam I According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “This governmental reign was prime for Egyptian military intervention. In 925 B.C., in a highly successful campaign, the like of which had not been seen since the days of Ramesses III in the 20th Dynasty, they were defeated. He moved first against Judah, arriving before the walls of Jerusalem, held by Rehoboam.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Jerusalem “was surrounded but Sheshonq was bought off from entering it by being given the treasures of the House of the Lord and the treasures of the kings house. All of Solomon's treasures, except the most sacred and emotive Ark of the Covenant, fell to Sheshonq. Pharaoh then turned his attentions to Israel, pursuing his earlier protégé Jeroboam, who fled over the Jordan River. Finally, Sheshonq halted at Megiddo, the scene of Thutmose III's victory 500 years before, and erected a victory Stele in the manner of his predecessors. Around 920 B.C. the kingdom of Judah fell apart, and the Jewish people split into groups. This was the time of the prophets. Later Judah was conquered by the Assyrians and then the Neo-Babylonians.

Leaders of Twenty-Second Dynasty

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Osokon I, who succeeded his father Shoshenk I, founder of the 22nd Dynasty, “continued to provide strong patronage for the various leading priesthoods, thereby consolidating his position as well as maintaining a continuous building program, especially at his native city of Bubastis. The chief priesthood of Amun at Karnak was taken from his brother Input and given to one of his sons, Sheshonq(II) whom he took as a co-regent in 890 B.C. Sheshonq, however, died a few months earlier than his father, and both were buried at Tanis. The successor was Takelot I, another son of Osokon by a minor wife. This reign, although 15 years in length, has left no major monuments, but saw the beginning of the fragmentation of Egypt once more into two power bases. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Osokon II succeeded Takelot I as pharaoh in 874 B.C. at much the same time that his cousin Harsiese succeeded his father (Sheshonq III) as High Priest of Amun at Karnak. Problems arose in year 4 of Osokon II when Harsiese declared himself king in the South. Although he was only king in name, when Harsiese died Osokon II consolidated his own position by appointing one of his sons, Nimlot, as High Priest at Karnak and another son, Sheshonq, as High Priest of Ptah at Memphis. Osokon II thereby had the two major priesthoods of Egypt in his families grasp as a political more rather than from any religious motivation. +\

“Takelot II succeeded his father Osorkon II in 850 and maintained stability in the South where his half brother Nimlot had consolidated his position by extending North to Herakleopolis and placing his son Ptahwedjankhef in charge there. Nimlot then married his daughter Karomama II to Takelot II, thereby cementing a bond between North and South and becoming the father-in-law of his half brother. The Crown Prince, Osorkon, never succeeded to the throne because his younger brother Sheshonq moved to seize power, proclaiming himself pharaoh as Sheshonq III with a reign of 53 years. +\

“Harsiese reappeared as Chief High Priest of Amun, apparently without too much commotion at Thebes because Sheshonq had let the Thebans have their own way and choice. In 806 B.C., the usurped Prince Osorkon was appointed to the High Priests' post at Thebes. Unusually, he had not been disposed of by his usurping younger brother. Then in 800 B.C. Harsiese once again assumed the office of High Priest, only to disappear, maybe dead. Prince Osorkon had not died when Harsiese returned to power and was still evident in Upper Egypt with a controlling hand for another 10 years.” +\

Twentieth Third Dynasty 818 – 715 B.C.

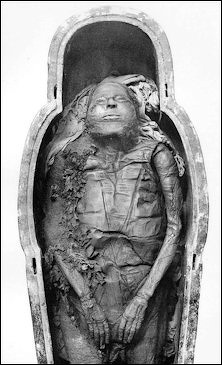

Third Intermediate Period mummy

“Under Takelot II (ca. 850–825 B.C.), the control of Dynasty 22 began to weaken, and a new power center—now known as Dynasty 23 (ca. 818–712 B.C.)—arose in the eastern Delta. The two dynasties governed Egypt simultaneously for approximately ninety years, the final stage of the Third Intermediate Period. By the end of the eighth century B.C., Egypt had fragmented further, particularly in the north, where a host of small local rulers held sway: in the eastern Delta, Osorkon IV (ca. 730–712 B.C.) of Dynasty 22 and Iuput II (ca. 754–712 B.C.) of Dynasty 23; in the western Delta and Memphis, Tefnakht (ca. 724—717 B.C.) of Dynasty 24, ruling from Sais; in Hermopolis, a local kinglet named Namlot (ca. 740 B.C.); and at Heracleopolis, another local ruler, named Peftjaubast (ca. 740–725 B.C.). \^/

While Shoshenk III of the 22nd Dynasty was in power, a prince called Pedubast proclaimed himself king in the central Delta at Leontopolis. This meant there were two dynasties ruling at the same time: The twenty-second at Tanis and the twenty-third at Leontopolis. The situation became even more confusing when yet a third man claimed to be king. The weak government that resulted allowed the Nubians to exert a strong influence in southern Egypt. The Kings at Leontopolis were: Pedubast I 818-793 B.C.; Iuput I; Shoshenk IV 780 B.C.; Osorkon III 777-749 B.C. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

The 23rd Dynasty leaders where Libyans. According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The twenty-third dynasty was part of a confusing period of overlapping dynasties including the twenty-first on through to the twenty-fifth dynasties respectively. It was a dynasty marked by Libyan control. It was started by Shoshenk I, an energetic soldier of Libyan descent. Shoshenk’s forbearers were the captives/ mercenaries under Ramses III used to stem the tide of barbarian incursions plaguing Egypt at the time. Not only were the Sea Peoples encroaching on Egypt’s borders, but also Shashank’s fellow Libyans. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Shashank’s rise to power was aided by the fact that Middle Egypt was a no-man’s land. It was this that opened the door for Libyan ascension. They seized this area and made their capital in Bubastis. At this time Shoshenk took care to legitimize his claim to the throne for his successor by marrying his son to the daughter of Psousennes II. Shaoshenk knew that to keep power he had to gain wealth. He did this by exploiting the break up of the Palestinian government after the death of Solomon. Shoshenk attacked Judah, the weaker of the two and sacked Jerusalem. It was with this brief yet rich conquest that further secured Libyan dominance. This dominance, which spanned from 950-730 B.C. was brought down when the Nubian king, Piankhi, invaded Egypt fearing further consolidation of power would challenge his growing countries strength. This invasion brought about the twenty-fifth dynasty and a close to Libyan dominance in Egypt.” Under the Libyan Pharaohs, “a school of palace artists flourished. They showed considerable skill in making bronze, silver and gold, even though little has survived.” +\

Twentieth Fourth Dynasty 727 – 715 B.C.

During this short twelve-year dynasty the Kings at Sais attempted to counter the Nubian threat by forming a coalition but the attempt failed. The two kings of this period were Tefnakht and Bakenrenef The 24th Dynasty was the last dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Tefnakht, the king of Sais in the Delta, attempted to put a stop to an invasion by organizing a coalition of northern kings that included Osorkon IV of Tanis, Peftjauabastet of Hernopolis, Nimlot, Input of Leontopolis and Tefnakht who became the first of the only two kings of the 24th Dynasty. The other was Bakenrenef, better known in Greek Myth as the Bocchoris who tangled with Herakles. Tefnakht reigned for approximately eight years and Bakenrenef for six years. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +] “The confederation of northern rulers enjoyed a certain success in that the Nubian King, Piankhi, allowed them to come south. The two forces met at Herakleopolis and Tefnakht and were compelled to retreat to Hernopolis where he and the other kings of the coalition surrendered to Piankhi.. All four kings were then allowed to continue as governors of their respective cities, a policy which centuries later Alexander the Great was to find effective in his world conquest +\

Notable Third Intermediate Period Rulers

Psusennes of the 21st Dynasty (989-943 B.C.): According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Psusennes I was chief priest of Amun at Tanis. He also renamed himself "Ramses-Psusennes" as a way to be able to be traced in family lineage back to Ramsses. Psusennes I was the son of Pharaoh Pinudjem I. Psusennes I name means "The Star Appearing in the City". Psusennes I strengthened his links with the priesthood of Amun by marrying his daughter Istenkhed to the chief priest Menkhperre. At Tanis, Psusennes I built a new enclosure around the temple dedicated to the triad of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. Psusennes I was buried in his tomb at Tanis with his wife Mutnedjmet. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Shoshenk I of the 22nd Dynasty (945–924 B.C.) : “Shoshenk I was the founder of the 22nd Dynasty which is often referred to also as the Libyan or Bubastite Dynasty. He was a strong militaristic ruler who brought the divided Egypt of the time back together into a unified force by once again uniting Thebes and Tanis. He placed his sons into high positions in the government, then turned his attention outward, looking for conquest. +\

“His attention roamed to the Palestinian kingdoms of Judah run by Rehoboam (Solomon's Son) and Israel under Jeroboam I. He considered them easy prey because of the internal strife which was existing in their country. By 946 B.C., as recorded in the Bible, Shoshenk defeated them both in a highly successful campaign. Also according to the Bible, Shoshenk took all the treasure of Jerusalem, including the golden shields Solomon had made and left only the Arc of the Covenant. Shortly after the triumphant battles, Shoshenk died and was buried in his family's tombs in Tanis. +\

Osoraken I of the 22nd Dynasty (924-889 B.C.): “Osoraken I was the son of Shoshenk I and later became the second Pharaoh of the 22nd Dynasty. Osoraken I continued to provide strong leadership throughout this period for the kingdom of Egypt. He is noted for removing his brother from the chief priesthood of Amun at Karnak and putting his son, Shoshenk II, in his place in 840 B.C. +\

Tefnakht of the 24 Dynasty (724–717 B.C.): “Tefnakht was the first king of the 24th Dynasty in Egypt, also known as the Sais Dynasty. He was king from 727-720 B.C. He was one of only two kings of the dynasty. He attempted to put a stop to an invasion by organizing other Northern Kings with him against the invaders from the south. This southern force was comprised of Piankhi’s Nubian forces that wanted to gain control of all of Egypt. The four northern armies under Tefnakht, Osorkon IV of Tanis, Peftjauabastet of Hernopolis, and Nimlot, Input of Leontopolis all enjoyed a relatively easy time in their conquering of the people down to the south, but Piankhi was actually drawing them down. When Tefnakht's forces finally reached Memphis they were massacred and Tefnakht conceded to Piankhi. Tefnakht and the four other leaders were allowed to remain governors of their territories under the new Pharaoh Piankhi. +\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024