Home | Category: Desert Animals

CARACALS

Caracals (Caracal caracal) are the largest of the small wild cats. They are nocturnal predator with distinctive long ears that have long tufts of black hair at their tips. They stand about 37 to 50 centimeters (15 to 20 inches) at the shoulder, weigh 11 to 20 kilograms (25 to 45 pounds) and reach lengths of 1.3 meters (four feet) including a 30 centimeter (one foot) tail. They vary in color from silver grey to tawny to brick red.

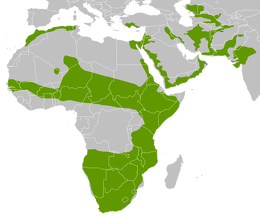

Caracals live mostly in Africa but they are also found in the Middle East, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and western India. They are seen during the day but they hunt mainly at night. Uncommon but fairly widely distributed, they feed on small game, rodents and birds.

Three subspecies are recognized:

1) Southern caracals (C. c. caracal) in Southern and East Africa;

2) Northern caracals (C. c. nubicus) in North and West Africa;

3) Asiatic caracals (C. c. schmitzi) in Asia;

Caracals are solitary animals that often feed mostly on birds and rodents. They have been observed leaping six feet in the air to make a kill and sometimes they bring down small antelope. According to the Smithsonian Institute these “supremely acrobatic” cats are “excellent jumpers and climbers,” and they regularly stalk their prey before pouncing when they within range to attack. They mainly hunt at twilight but are also active at night, in hot weather and during the daytime in the winter. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, October 21, 2023]

Caracals are also known as “barking cats” because of the barking noise they make when threatened. They hiss when excited or scared. They are sometimes mistaken for lynxes because of their tufted ears.In recent decades caracals have been adopted by people as pets. They have lived up to 20.3 years raised in captivity. Their average lifespan in the wild is estimated to be 12 years.

Caracal Range and Habitat

Caracals live in temperate and tropical areas in savannas, deserts, grasslands, forests, scrub forests, thickets, plains and rocky hills at elevations up to 3,000 meters (9,842 feet). They prefer edge habitats, especially forest-grassland transitions, in places with an arid climate and minimal foliage cover. They can tolerate dry conditions but are seldom found deserts or tropical environments. In Asia, caracals are sometimes found in forests, which is uncommon in Africa. [Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Caracals range over much of Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and southwestern Asia. North African populations are disappearing, but caracals are still abundant several parts of Africa. Their range limits are the Saharan desert and the equatorial forest belt of Western and Central Africa. In South Africa and Namibia, caracals are so numerous that they exterminated as pests.

The population densities of Asiatic caracal are less than those of Africa and Asiatic populations are more threatened. The historical range of caracals parallels of cheetahs — which still in parts of Iran and have been re-introduced to India — and both coincide with the distribution of several small desert gazelles. There is little to no distribution overlap with African golden cats — a similar species — but caracals do share a significant portion of their range with servals in Africa and with wildcats (Felis sylvestris), specifically the subspecies Felis silvestris lybica (African wildcats) and Felis silvestris ornata (Asian wildcats) in Africa and Asia.

Caracal Characteristics

Caracals range in weight from eight to 19 kilograms (17.6 to 41.8 pounds and have a head and length of 62 to 91 centimeters (about two to three feet). Tail length ranges from 18 to 34 centimeters (7 to 13 inches). Even the smallest adult caracal is larger than most domestic cats. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females): Males are larger than females. Females weigh around 13 kilograms while males can weigh up to 20 kilograms.[Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Caracals have brown to red coats, with color varying among individuals. Females are typically lighter than males. Their undersides are white and, similar to African golden cats, are adorned with many small spots. The face has black markings on the whisker pads, around the eyes, above the eyes and faintly down the center of the head and nose.

The most distinguishing features of caracals are their elongated and black-tufted ears. The legs are relatively long and the hind legs are disproportionately tall and well muscled, allowing them to sprint very fast. Eye color varies from golden or copper to green or grey. Juveniles have shorter ear tufts and blue tinted eyes.

Caracal Food, Diet, Hunting and Predators

Caracals are carnivores and mostly eat birds, mammals, reptiles. The majority of their diet is made up of hyraxes, hares, rodents, antelopes, small monkeys, and birds. Doves and partridges are seasonally important. Mountain reedbucks, Dorcas gazelles, Kori bustards, mountain gazelles, gerenuks and Sharpe’s grysboks are examples of some of the big animals that caracals hunt. Caracals consume some reptiles, although they not a common component of their diet. [Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The diet or caracals varies according to to where they live. Individuals in Africa are more likely to consume larger animals such as antelope while ones in Asia are more likely to feed predominately on small vertebrates, such as rodents. Livestock are sometimes hunted. Although caracals are famous for leaping in the air to catch bords, mammals make up over half of their diet in all ranges.

Unique among relatively small, cats, caracal are able to take down prey two to three times larger than themselvess. Small prey such as marmots and pikas are killed with a bite to the nape, while large prey, such as gazelles are killed with a suffocating throat bite. Prey are usually stalked to within a few long bounds, then captured when the caracal leaps using its disproportionately long and muscular back legs. Perhaps a result of their opportunistic appetite, caracals may engage in surplus killing (killing more than they can eat, sometimes viewed as a kind of cruel sport). Unlike leopards, caracals rarely take their kill into trees. Instead they scrape earth over an unfinished carcass and periodically return to feed on it until it is finished.

Lions, leopards and hyenas may prey on caracals but rarely do so. Camouflage is a primary defense against predators. When threatened caracals often lie flat and don’t move and their plain, brown coats act as instant camouflage. Agile climbing abilities also aid caracals in escaping larger predators such as lions and hyenas.

Caracal Behavior

Caracals are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (live on the ground), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), terricolous (living in the ground or in the soil), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range) and soliatery. The size of their range territory is four to 316 square kilometers. [Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Caracals maintain a large home range for their size. Climate, region, and sex all influence home range size. The home range of males is usually twice that of females. Home range size is also influenced by the availability of water — with home ranges in arid climates large than those elsewhere. In parts of Africa the territory of males ranges from 31 to 65 square kilometers whole those of females a range from four to 31 square kilometers. In parts of Asia, males commonly maintain home ranges of 200 to over 300 square kilometers. There are a sex difference in way territories are defended. The territory of males may overlap with the territories of several other males, while female defend their entire territory for their own use.

Caracals are solitary, except during mating period and the rearing of kits. Although primarily active at night, caracals may be seen during the day, especially in undisturbed regions. Though they are terrestrial, they are also good at climbing trees and rocks and have been described as having a tenacious disposition. A single caracal has been known to chase off predators up to twice its size. Hunting time is usually determined by when their prey are most active; caracals are most often seen hunting at night.

Caracal Senses and Communication

Caracals sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Much of the information on caracals senses and communication comes from individuals in captivity.. [Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Like other cats, caracals have well-developed senses of sight and hearing. They can detect small prey by sound alone. Once prey are detected, vision is used to zero in exactly where it is. The function of the ear tufts on caracals is unknown. Some zookeepers speculate that they may be used in communication with other caracals. If this is the case, then maybe they are not as solitary as people think they are.

Caracals produce growls, spits, hisses and meows. In captivity, they are known for their grating vocalizations. Tactile communications, such as sparring and huddling, have been observed during mating periods. potential mates are attracted by olfactory cues. Hormonal changes in the female result in a change in urine composition. When females are ready to mate, they deposit her their scent in various locations to attract males. Males may perceive the scent with their vomeronasal organ.

Caracal Mating and Reproduction

Caracals are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They are capable of breeding year-round but usually engage in seasonal mating between August and December so that young are born in the summer. The gestation period ranges from 68 to 81 days. The number of offspring ranges from one to six, with the average number of offspring being three. The time mothers spend with their kits (and the combined lack of post partum estrus) restricts females to one litter per year. In the 1990s, a captive caracal mated with a domestic cat in the Moscow Zoo, resulting in a hybrid offspring.[4[Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Lauren Phillips wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Before mating begins, chemical signals in the female’s urine attract and notify the male of her readiness to mate. A distinctive “cough-like” mating call has also been reported as a method of attraction. There have been several different forms of mating systems observed for caracals. When a female is being courted by multiple males, the group may fight to mate with her or she may choose her mates, preferring older and larger males to younger and smaller males. Mating may occur with multiple individuals over the course of about a week. When a female chooses a mate, the pair may move together for up to four days, during which copulation occurs multiple times. Female caracals assume a lordotic position and copulation lasts for less than five minutes on average. Females almost always copulate with more than one male. Infanticide by males has been observed. This may be to induce ovulation in a female undergoing lactational amenorrhea. /=\

Although both sexes are sexually mature at seven to 10 months, the earliest successful copulation will occur around 14 to 15 months of age. Some biologists believe that sexual maturity is indicated by a body mass of seven to nine kilograms. Females exhibit estrous behaviors for three to six days but the cycle actually lasts twice as long. A female may go into estrus at any time during the year. One hypothesis to explain the breeding habits of Caracals is the “use” of an opportunistic strategy. This strategy is controlled by the female’s nutritional status. When a female is experiencing pinnacle nutrition (which will vary by range), she will go into estrus. This explains peak birth timing between October and February in some regions.

Caracal Offspring and Parenting

Caracals are are altricial. This means that young are born relatively underdeveloped and are unable to feed or care for themselves or move independently for a period of time after birth. /=\ During the pre-weaning and pre-independence stages of development provisioning and protecting are done by females. Once the young are conceived, males play no role in the direct or indirect care of young. Females invest a great deal of time and energy into their young. The age in which caracal young are weaned ranges from four to six months and the age in which they become independent ranging from nine to 10 months. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at seven to 10 months. [Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Births generally peak from October to February and take place in dense vegetation, a tree cavity, cave, or deserted burrows of other animals. Kittens are born with their eyes and ears shut and the claws not retractable (unable to be drawn inside). Their coats resemble the coats of adults, but the abdomen is spotted. Eyes open by ten days, but it takes longer for the vision to become normal. The ears become erect and the claws become retractable by the third or the fourth week. [Source: Wikipedia

Mothers may continuously move her young. At around one month of age, caracal kittens leave their dens for the first time start roaming around and start playing among themselves by the fifth or the sixth week. Kits begin taking solid food around the same time and make their first kill at about three months. . As the kittens start moving about by themselves, the mother starts shifting them every day. All the milk teeth appear in 50 days, and permanent dentition is completed in 10 months. Juveniles begin dispersing at nine to ten months, though a few females stay back with their mothers.

Caracals, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List caracals are listed as a species of Least Concern. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status as they are widely distributed in over 50 range countries, where the threats to caracal populations vary in extent The Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) lists Asian populations as Appendix I, I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. All others are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. [Source: Lauren Phillips, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Humans have utilized caracals for the pet trade and their body parts are sources of valuable materials. In India and Persia, caracals were once trained to catch game birds and deer. In this way they provided both food and entertainment. Bushmeat and pelts in western and central Africa provide food and minor profit for locals. Luckily for caracals, their plain pelt is in very low demand.

The Primary threat to caracals is habitat loss in northern, central, and western Africa and Asia. Predation on small livestock has resulted in extermination of thousands of caracals in South Africa and Namibia, where predator control programs have been enacted. in place. Even when such programs are put in place, caracals quickly recover and go after small livestock.

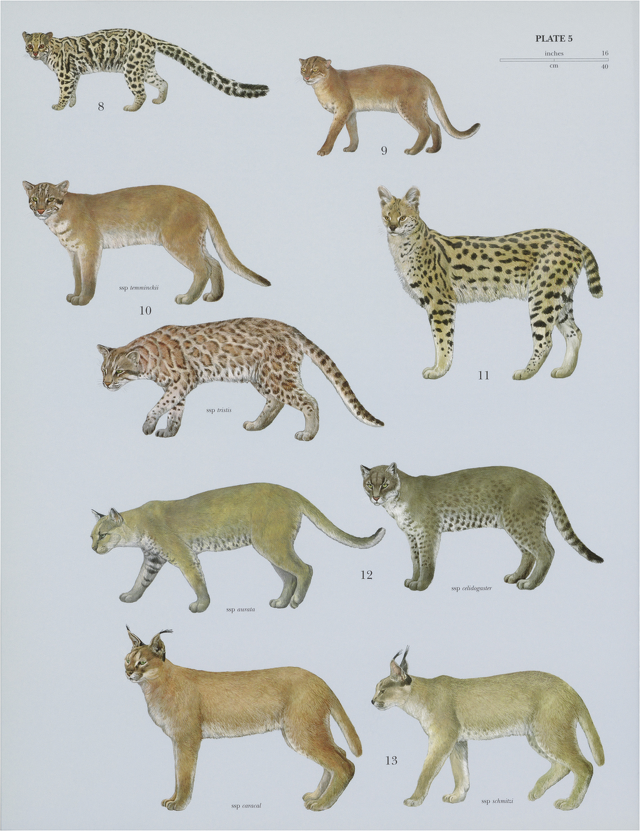

Caracal and some of its relatives: 8) Marbled Cat (Pardofelis marmorata), 9) Bay Cat (Catopuma badia), 10) Asian Golden Cat (Catopuma temminckii), 11) Serval (Leptailurus serval), 12) African Golden Cat (Profelis aurata), 13) Caracal (Caracal caracal)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025