Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ASTRONOMY

The Egyptians of the New Kingdom, if not those of earlier date, possessed the elements of real astronomy. On the one hand they tried to find their way in the vastness of the heavens by making charts of the constellations according to their fancy, charts which of course could only represent a small portion of the sky. On the other hand they went further, they made tables in which the position of the stars was indicated. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sara Moldaschel of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “The Ancient Egyptians had a limited knowledge of astronomy. Part of the reason for this is that their geometry was limited, and did not allow for complicated mathematical computations. Evidence of Ancient Egyptian disinterest in astronomy is also evident in the number of constellations recognized by Ancient Egyptians. At 1100 B.C., Amenhope created a catalogue of the universe in which only five constellations are recognized. They also listed 36 groups of stars called decans. These decans allowed them to tell time at night because the decans will rise 40 minutes later each night. Theoretically, there were 18 decans, however, due to dusk and twilight only twelve were taken into account when reckoning time at night. Since winter is longer than summer the first and last decans were assigned longer hours. Tables to help make these computations have been found on the inside of coffin lids. The columns in the tables cover a year at ten day intervals. The decans are placed in the order in which they arise and in the next column, the second decan becomes the first and so on. [Sources: Sara Moldaschel Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, “The Cambridge Illustrated History of Astronomy.” Michael Hoskin, ed. Cambridge University Press,1997; Springer-Verlag and Hugh, Thurston. “Early Astronomy,” New York, Inc. 1994]

“Astronomy was also used in positioning the pyramids. They are aligned very accurately, the eastern and western sides run almost due north and the southern and northern sides run almost due west. The pyramids were probably originally aligned by finding north or south, and then using the midpoint as east or west. This is because it is possible to find north and south by watching stars rise and set. However, the possible processes are all long and complicated. So after north and south were found, the Egyptians could look for a star that rose either due East or due West and then use that as a starting point rather than the North South starting point. This would result in the pyramids being more accurately aligned with the East and West, which they are, and all of the errors in alignment would run clockwise, which they do. This is because of precession of the poles which is very difficult to view, and the Ancient Egyptians did not know about. This theory is further substantiated by the fact that the star B Scorpii’s rising-directions match with the alignment of the pyramids on the dates at which they were built. +\

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Astronomy” by Norman Lockyer (1894) Amazon.com;

“Architecture, Astronomy and Sacred Landscape in Ancient Egypt” by Giulio Magli (2013) Amazon.com;

“Dendera, Temple of Time: The Celestial Wisdom of Ancient Egypt” by José María Barrera (2024) Amazon.com;

“Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred” by Jeremy Naydler (1996) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy of Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Perspective” by Juan Antonio Belmonte, José Lull, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science: Source Book. Volume I: Knowledge and Order” by Marshall Clagett (1989) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. III: A Source Book, Ancient Egyptian Mathematics” by Marshall Clagett (1999) Amazon.com;

”Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs” by Richard J. Gillings (1982) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Astrology

In the clear Egyptian sky the stars are wonderfully bright, and the inhabitants of the Nile valley must have observed them in very early ages. Though they did not, like the dwellers in Mesopotamia, regard them as divinities, yet they looked upon them as the abode of pious souls. For example the dog-star (Sirius) — the so-called Sothis, was regarded as the soul of Isis, Orion as that of Horns. Other stars were the genii with whom the sun was connected in his course; they thus especially regarded the 36 constellations situated on the horizon, the so-called decan stars. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In ancient times astrology and astronomy were the same thing. The Babylonians were the first people to apply myths to constellations and astrology and describe the 12 signs of the zodiac. The Greeks and Romans borrowed some of their myths from the Babylonians and invented their own. The word astrology (and astronomy) are derived from the Greek word for "star."

The Egyptians refined the Babylonian system of astrology and the Greeks shaped it into its modern form. Astrology as we know it originated in Babylon. It developed out of the belief that since the Gods in the heavens ruled man's fate, the stars could reveal fortunes and the notion that the motions of the stars and planets control the fate of people on earth. The motions of the stars and planets are mainly the result of the earth’s movement around the sun, which causes: 1) the sun to move eastward against the background of the constellations; 2) the planets and moon to shift around the sky; and 3) causes different constellations to rise from the horizon at sunset different times of the year. The names and shapes of many the constellations are believed to date to Sumerian times because the animals and figures chosen held a prominent place in their lives. It is thought that if the constellations originated with the the Egyptians were would ibises, jackals, crocodiles and hippos — animals in their environment — rather than goats and bulls. If they came from India why isn’t there a tiger or a monkey. To the Assyrians the constellation Capricorn was munaxa (the goat fish). The Greeks added names of heroes to the constellations. The Romans took these and gave them the Latin names we use today. Ptolemy listed 48 constellations. His list included ones in the southern hemisphere, which he and the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks and Romans couldn’t see.

Ancient Egyptian Beliefs About Astrology

The Egyptians believed that a man's destiny was decided before birth and astrologers were consulted about where fate would take them. The well-known Egyptologist Sir E. A. Wallis Budge wrote: "In magical papyri we are often told not to perform certain magical ceremonies on such and such days, the idea being that on these days hostile powers will make them to be powerless, and that gods mightier than those to which the petitioner would appeal will be in the ascendant. There have come down to us fortunately, papyri containing copies of the Egyptian calendar, in which each third of every day for three hundred and sixty days of the year is marked lucky or unlucky, and we know from other papyri why certain days were lucky or unlucky, and why others were only partly so." [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“In the life of Alexander the Great by Pseudo-Callisthenes it is noted that the Egyptians were skilled in the art of casting horoscopes. Nectanebus had a tablet made of gold and silver and acacia wood, with three belts attached to it, just for that. Zeus was on the outer belt with the 36 decani surrounding him; representations of the 12 signs of the zodiac were on the second; and the third the sun and moon were on the third. He set the tablet on a tripod, and emptied out of a small box with models of the seven stars that were in the belts, and put eight precious stones into the middle belt. He arranged these in the places where he figured the depicted planets would be at the time of the birth of Olympias. He then told her fortune from them.

“It should be noted that the use of the horoscope is much older than the time of Alexander the Great. A Greek horoscope in the British Museum is attached to "an introductory letter from some master of the art of astrology to his pupil, named Hermon, urging him to be very exact and careful in his application of the laws which the ancient Egyptians, with their laborious devotion to the art, had discovered and handed down to posterity."

Ancient Egyptian Astrology and the Cairo Calendar

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Most of our understanding of Egyptian astrology is contained within the Cairo Calendar, which consists of a listing of all the days of an Egyptian year. The listings within the calendar all take the same form and can be broken up into three parts: I, the type of day (favorable, unfavorable etc), II, a mythological event which may make a particular day more favorable or unfavorable, III, and a prescribed behavior associated with that day. Unlike modern astrology as found within newspapers, where one can choose whether to follow the advice there in or not, the Egyptians strictly adhered to what an astrologer would advise. As is evidenced by the papyrus of the Cairo Calendar, on days where there were adverse or favorable conditions, if the astrologers told a person not to go outside, not to bathe, or to eat fish on a particular day, such advice was taken very literally and seriously. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Some of the most interesting and misunderstood information about the Ancient Egyptians concerns their calendarical and astrological system. Of the greatest fallacy about Ancient Egypt and it's belief in astrology concerns the supposed worship of animals. The Egyptians did not worship animals, rather the Egyptians according to an animals astrological significance, behaved in certain ritualistic ways toward certain animals on certain days. For example, as is evidenced by the papyrus Cairo Calendar, during the season of Emergence, it was the advisement of the Seers (within the priestly caste), and the omens of certain animals they saw, which devised whether a specific date would be favorable or unfavorable. +\

“The basis for deciding whether a date was favorable or unfavorable was based upon a belief in possession of good or evil spirits, and upon a mythological ascription to the gods. Simply, an animal was not ritually revered because it was an animal, but rather because it had the ability to become possessed, and therefore could cause harm or help to any individual near them. It was also conceived of that certain gods could on specific days take the form of specific animals. Hence on certain days, it was more likely for a specific type of animal to become possessed by a spirit or god than on other days. The rituals that the Egyptians partook of to keep away evil spirits from possessing an animal consisted of sacrifice to magic, however, it was the seers and the astrologers who guided many of the Egyptians and their daily routines. Hence, the origin of Egyptians worshipping animals, has more to do with the rituals to displace evil spirits, and their astrological system, more so than it does to actually worshipping animals.” +\

Zodiac Symbols Found in 1,800-Year-Old Ancient Egyptian Temple

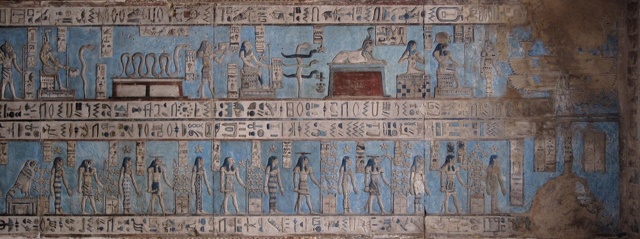

The zodiac system was developed by the Babylonians in the Near East and was introduced to Egypt at the end of the fourth century B.C. A.D. third century images on the ceiling in the entrance hall of Egypt’s Temple of Esna, recently cleaned by an Egyptian-German team of researchers, led by Hisham El-Leithy of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and Christian Leitz of the University of Tübingen, include planets Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, as well as representations of decans, or stars and constellations that were used to measure time. It displays strange hybrid animal creatures, which are identified in accompanying inscriptions and may represent constellations. The ceiling also features depictions of the 12 signs of the zodiac. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2023]

During the Ptolemaic period (304–30 B.C.), Leitz explains, the signs became quite popular among Egyptians, who adorned their tombs with their birth signs and inscribed horoscopes on ostracons, broken pottery pieces used as writing surfaces. Nevertheless, the Esna zodiac is one of only three preserved in Egyptian temples. “It’s astonishing because in a normal Egyptian temple, there isn’t anything showing foreign influence,” Leitz says. “This is a remarkable exception.”

The Temple of Esna, also known as the Temple of Khnum, was dedicated to the ancient Egyptian deity, Khnum, believed to have created humans on a pottery wheel. Construction of the temple began in 186 B.C. and finished around 250 A.D. All that remains of the structure is a grand hall with 24 columns, officials said. Every available surface of the temple — from the base of the columns to the ceiling 50 feet above — is covered in inscriptions, carvings and painted designs, the University of Tübingen said The intricate designs of the Temple of Esna were “roughly chiseled out, the details only applied by painting them in color,” Egyptologist Christian Leitz said in the University of Tübingen’s news release. The details have only become visible again through restoration efforts. Esna is about 675 kilometers (420 miles) southeast of Cairo. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, March 21, 2023]

According to the Miami Herald: Two red figures, mirroring each other and holding hands, represent the Gemini sign. A yellow scorpion surrounded by white stars represents the Scorpio sign, and a two-faced centaur-like creature with a bow and arrow represents Sagittarius. One of the constellations previously uncovered is the Big Dipper, according to the University of Tübingen. The ancient Egyptian representation of this constellation is a bull’s leg, which “is tied to a stake by a goddess in hippo form,” archaeologists said. The tan-brown design represents the seven-star constellation, photos show.

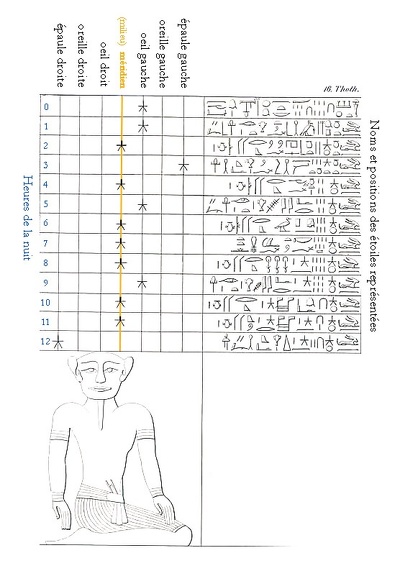

Ancient Egypt Star Tables

The Ancient Egyptians imagined that under the center of the sky a human figure sat upright, and that the top of his head was placed below the zenith. The stars which were approaching the zenith were situate over a portion of this figure, and their position was indicated in the lists of stars. There are several of these kinds of lists in the tombs of the kings of the 20th dynasty; they give the position of the stars during the twelve hours of the night, at intervals of fifteen days. Unfortunately, as they only served as pieces of decorative work for the tomb, they were very carelessly done, and it is therefore very difficult to make them out. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

On the 16th of Paophi, for instance, they thus indicated the position of the stars during:

1st hour — the leg of the giant over the heart and over the left eye.

2nd hour — the star I'ctef

3rd hour — the star 'Ary

4th hour — the claw of the goose

5th hour — the hinderijart

6th hour — the star of thousands

7th hour — the star S'ar

8th hour — the fingerpoint of the constellation S'ah (Orion) over the left eye.

9th hour — the star of S'ah (Orion) over the left elbow.

10th hour — the star that follows Sothis over the left elbow

11th hour — the fingerpoint of both stars over the right elbow.

12th hour — the stars of the water over the heart.

After fifteen days, on the 1st of Athyr, the stars have changed their positions as follows:

1st hour — Star Petef

2nd hour — Star 'Ary

3rd hour — Head of the goose

4th hour — Hinderpart of the goose

5th hour — Star of the thousands

6th hour — Star of the S'ar

7th hour — Point of finger of the S'ah

8th hour — Star of the S'ah

9th hour — Star that follows Sothis

10th hour — Fingerpoint of both stars

11th hour — Stars of the water

12th hour — Head of the lion

And again after fifteen days on the 16th:

1st hour — Star 'Ary

2nd hour — Head of the goose

3rd hour — Hinderpart of the goose

4th hour — Star of the thousands

5th hour — Star of the S'ar

6th hour — Star of the S'ah

7th hour — Star of the S'ah

8th hour — Star that follows Sothis

9th hour — Fingerpoint of both stars

10th hour — Stars of the water

11th hour — Head of the lion

12th hour — Tail of the lion

Ancient Egyptian Views of the Earth, Sky and Stars

The ancient Egyptians used astronomical data and the solar calendar to determine the dates of religious and official rituals, such as the coronation of kings and the agricultural year. Inside an astronomical observatory scientists found an inscribed stone depicting astronomical views of sunrise and sunset across three seasons. Such findings confirm the ancient Egyptians' deep understanding of seasonal changes and variations in day length. [Source Reham Atya, Live Science, August 30, 2024]

The ancient Egyptians viewed the Earth and sky as two mats. They mapped the sky on the 'Themet Hrt' — the sky mat — and the 'Themet Ghrt,' or Earth mat, represented their calendar, marking events like the Nile flood and harvest. Horus, along with an eye of Horus, "embodies the systems of the universe and is linked to the sun, the moon, the god Horus, and the goddess Wadjet.

Sara Moldaschel of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: Ancient Egyptians also used astronomy in their calendars. There life revolved the annual flooding of the Nile. This resulted in three seasons, the flooding, the subsistence of the river, and harvesting. These seasons were divided into four lunar months. However, lunar months are not long enough to allow twelve to make a full year. This made the addition of a fifth month necessary. This was done by requiring the Sirius rise in the twelfth month because Sirius reappears around the time when the waters of the Nile flood. Whenever Sirius arose late in the twelfth month a thirteenth month was added. This calendar was fine for religious festivities, but when Egypt developed into a highly organized society, the calendar needed to be more precise. Someone realized that there are about 365 days in a year and proposed a calendar of twelve months with 30 days each, with five days added to the end of it. However, since a year is a few hours more than 365 days this new administrative calendar soon did not match the seasonal calendar. [Sources: Sara Moldaschel Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, “The Cambridge Illustrated History of Astronomy.” Michael Hoskin, ed. Cambridge University Press,1997; Springer-Verlag and Hugh, Thurston. “Early Astronomy,” New York, Inc. 1994]

Ancient Egypt’s “First and Largest” Astronomical Observatory Discovered

In August 2024, archaeologists announced that they had identified the first ancient Egyptian astronomical observatory ever recorded and called it the "first and largest" of its kind, according to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. An Egyptian archaeological team discovered the remains of the sixth-century-B.C. structure in 2021 at an archaeological site in the ancient city of Buto, now called Tell Al-Faraeen, in Egypt's Kafr El-Sheikh governorate. "Everything we found shattered our expectations," Hossam Ghonim, director general of Kafr El-Sheikh Antiquities and head of the Egyptian archaeological mission, told Live Science. [Source Reham Atya, Live Science, August 30, 2024]

Live Science reported: The team uncovered the ruins of an L-shaped mud-brick building spanning over 850 square meters (9,150 square feet). Its east-facing entrance, marked by a traditional gateway known as a pylon, leads to a spot where sunlight would have illuminated where the sky observer — known as 'smn pe' and who was usually a priest — stood to track the sun and stars, Ghonim said. The structure still has a carving of smn pe facing the rising sun. This figure symbolizes the ancient Egyptians' connection to the cosmos, Ghonim said.

At first, the team thought they had discovered a temple. Yet, as the excavation progressed, they uncovered artifacts and inscribed symbols, such as Chen, Cenet and Benu, that related to time and astronomy, Ghonim said. But it was the discovery of a huge sundial — along with several inscriptions, artifacts and the layout of the building — that led researchers to make the new announcement that this structure was an observatory,

The archaeologists also found a "triad of pillars" at the hall's entrance — an unusual placement because the typical structure of ancient Egyptian monuments feature pillars at the end of the hall. This unusual placement of pillars suggests that it is not a temple, as previously thought. "We theorized that these pillars might represent the ancient Egyptians' tripartite division of time into seasons, months and weeks," Ghonim said. Unlike traditional monuments, which typically have a single pylon, the observatory had two pylons facing each other, framing the circular observatory spot and symbolizing akhet, or the horizon where the sun rises. Facing this Akhet was a limestone watchtower that was likely once paired with another and used to observe constellations, Ghonim said.

In ancient times, Buto was dedicated to the goddess Wadjet, a serpent goddess known to be protective of the king. The analysis of the observatory provides more evidence that Wadjet was of great importance to Buto, Ghonim said. Inside the observatory, archaeologists found a gray, granite statue of King Psamtik I from the Saite era — the 26th dynasty — and a bronze figure of Osiris, a god associated with the underworld and resurrection, with a serpent, referring to the goddess Wadjet. These artifacts, along with various pottery items used in religious rituals, date the observatory to the sixth century B.C. and emphasize its dual role in scientific study and spiritual practice, Ghonim said.

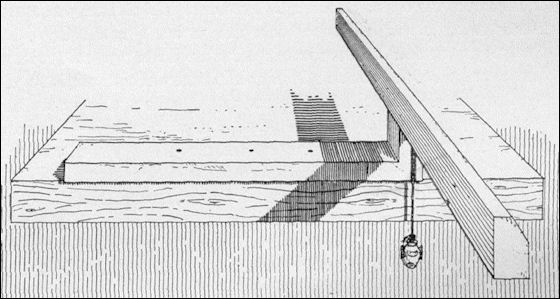

Inside Ancient Egypt’s “First and Largest” Astronomical Observatory

Elizabeth Howell wrote in Space: The mud-brick temple building was found in a larger complex known now as the Temple of Buto. A notable newfound tool was a "sloping stone sundial" that measured time by the movements of the sun. The temple building itself faced east, the direction from which the sun rises. Inside the building, the team found construction features that also suggested alignments with the sun. Three stone blocks on the ground, for example, were used to "take measurements of the sun's location." Another set of five flat limestone blocks mounted on long (16-foot, or 4.8 m) slabs had inclined lines "used to measure the inclinations of the sun and shadow, and to monitor the movement of the sun during daylight hours," the ministry wrote. [Source Elizabeth Howell, Space, August 30, 2024]

Ghonim explained. "Along the hall's northern side, we discovered a slanted stone sundial — a sun shadow clock that used the shifting angles of the sun's shadows to determine sunrise, noon and sunset — a simple yet profound method".The team also found an ancient Egyptian timekeeping device known as a "merkhet," also from the sixth century B.C., at the site.

The hall was also festooned with images of deities linked with the sky. For example, Horus (as a falcon) typically has a right eye symbolizing either the sun or the "morning star" Venus, while his left eye symbolizes the moon or "evening star" (also Venus, in its setting phase), according to Britannica. Horus is the son of Wadjet, the protector goddess of Lower Egypt after whom the temple is named, according to Britannica. Sometimes Wadjet and the deity Nekhbet, who represents Upper Egypt, are represented as an ensemble on the pharaonic jeweled crown or diadem, symbolizing how the pharaoh united both Upper and Lower Egypt.

Conceptualizations of the Moon in Ancient Egypt

Victoria Altmann-Wendling wrote: Our understanding of the moon as it was regarded in ancient Egypt from the Old Kingdom to the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods is based mostly on texts and images from temples, but also on stelae, coffins, and papyri. The conceptualizations can be categorized into those concerning astronomical properties of the celestial body (its shape, luminosity, motion, constellations), those in which the moon takes on anthropomorphic (man, child, eye, leg, arm) and zoomorphic (bull, ibis, baboon) forms, and those that have a socio-political background, concerning the reign of the pharaoh, the measuring and conception of time, and the maintenance of the cosmos (maat) as a whole. [Source: Victoria Altmann-Wendling, Universität Würzburg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2024]

Among the most important sources of information for our understanding of the moon are texts with discourses on the moon and (related) representations from temples, of which those from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods (around 300 B.C. –300 CE) predominate. These temples are mainly located along the Nile Valley, as far north as Athribis and as far south as Philae, but are also represented in the oases (Bahria, Dakhla, and Kharga) and Nubia (Soleb and Abu Simbel). That the moon is visually and textually represented with striking frequency on ceilings and door lintels on the north side of temples, combined with the assignment of the north to the night, illustrates the Egyptian perception of the temple as a cosmos. In addition, papyrus manuscripts dating mainly from the Roman Period are informative; they are almost entirely funerary, the moon being referenced there in connection with Osiris, the god of the dead. Supplementing these are sources from previous eras, beginning with the Old Kingdom (6th Dynasty, around 2300 B.C.), from temples, tombs, stelae, and coffins.

Since the earliest sources, the Pyramid Texts, most likely reflect previous stages of religion that have not survived or were transmitted only orally, it can be assumed that a moon god existed prior to their inscription. The distribution of the sources is, on the one hand, due to their preservation (the more recent papyri being the best preserved) and, on the other, to the tendency in Ptolemaic and Roman times for temple texts to become ever more detailed — sometimes downright encyclopedic — occupying virtually all available space on temple walls and ceilings, and written in smaller and more tightly set hieroglyphs compared to those of earlier phases.

The moon is frequently addressed in the texts as a disk of varying qualities, e. g., “bright,” “luminous,” “nocturnal,” “large,” “golden,” or “white,” referring to its luminosity, or in the case of the golden color, to its remarkable appearance especially at rise and set in the earth’s denser atmospheric layers nearest the horizon. References to other colors as well as to the “skin” of the celestial body might refer to its cratered surface, to its appearance during a lunar eclipse, or to its changing appearance depending on its phase and position (after all, the celestial body shows itself to earth’s inhabitants with a different shape every day). The dark areas of the moon (e. g., maria, the lava-lined craters informally referred to as the “Man in the Moon”) and lunar eclipses find no explicit mention; they are instead referred to indirectly, couched in the euphemism of Egyptian religious texts. Moreover, lunar eclipses were interpreted as omens with mostly negative implications manifestations within the lunation are, prior to the Roman Period, not explicitly designated or depicted.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Conceptualizations of the Moon by Victoria Altmann-Wendling escholarship.org

sundial

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024