ESTATES IN OLD KINGDOM (2649–2150 B.C.) EGYPT

Juan Carlos Moreno García of Université Charles-de-Gaulle wrote: “Estates (also referred to as “domains”) formed the basis of institutional agriculture in Old Kingdom Egypt. Estates were primarily administered by the temples or by state agricultural centers scattered throughout the country, but were also granted to high officials as remuneration for their services. Sources from the third millennium B.C. show that estates constituted production networks where agricultural goods were produced, stored, and kept available for agents of the king who were traveling on state business. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, Université Charles-de-Gaulle, France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Estates were one of the main sources of income for the Egyptian state during the Old Kingdom. Most preserved sources concern the estates of institutions such as temples or the administrative centers known as Hwt (plural: Hwwt), or of certain state officials, including some members of the royal family. As estates were scattered all over the country, they constituted the links in a network of royal warehouses, production centers, and agricultural holdings that facilitated the production and storage of agricultural goods that were kept at the disposal of institutions or of the royal administration when needed.

“There is an important difference between Old Kingdom estates and their counterparts in later, better-documented periods: whereas texts like the Ramesside Wilbour Papyrus evoke thousands of estates directly controlled by the temples (the most important economic centers of the country from the New Kingdom on), third-millennium inscriptions show that royal centers founded by the king and administered by state-appointed officials controlled many estates and were, along with the temples, prominent places of institutional agricultural production.

“The most ancient sources concerning estates and their integration into the economic structure of the Egyptian state date from as early as the pre-unification period. Labels from the tombs of the late-Predynastic kings at Abydos appear to mention localities and estates that produced goods for, or sent goods to, the royal mortuary complexes. Hundreds of inscribed vessels from the 3rd-Dynasty pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara contain brief references to the officials and centers responsible for delivering offerings to Djoser’s funerary monuments and to those of his predecessors.

Estates composed a vital element in the economic and fiscal organization of the Egyptian state during the Old Kingdom. It should be emphasized that most estates depended on a network of royal centers (mainly Hwt) directly administered by royal officials—a feature that characterizes the Old Kingdom—whereas in later periods of Egyptian history the temples became the main holders of estates, which were therefore subject to a more indirect and fragile control by the king.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Land Tenure In The Ramesside” by Sally L.D. Katary (2018) Amazon.com;

“Land and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt: The Structure of Land Tenure”

by J. G. Manning (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Management of Estates and their Resources in the Egyptian Old Kingdom”

by Joyce Swinton (2012) Amazon.com;

“Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern Times” by Alan K. Bowman and Eugene Rogan (1999) Amazon.com;

“Garden of Egypt: Irrigation, Society, and the State in the Premodern Fayyum by Brendan Haug (2024) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Irrigation: A Study of Irrigation Methods and Administration in Egypt (Classic Reprint) by Clarence T. Johnston (1901) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

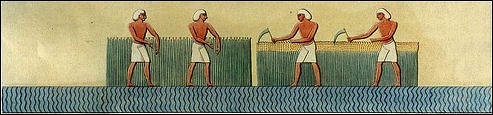

Organization of Estates in Ancient Egypt

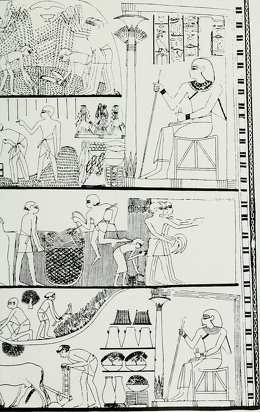

Numerous functionaries were of course necessary to direct large properties; these are frequently represented; there are “scribes," “directors of scribes," “stewards," “directors of affairs," “scribes of the granaries," etc. Very often the highest appointments in the supervision of property are given to the sons of the great lord. There was also always a special court of justice belonging to the estate, to supervise the lists of cattle," and before this court the mayor of the village would be brought when behindhand with the rents of his peasants. Besides the laborers there were numerous workmen and shepherds belonging to the property; these went out to war with their lord, and formed various bodies of troops, each bearing their own standard. " during the Middle Kingdom the conditions of large landed proprietors appear to have exactly resembled those above described. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

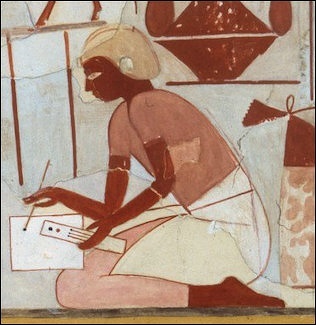

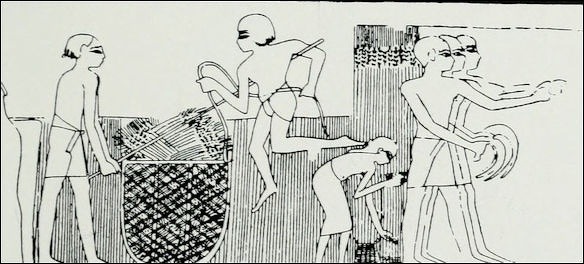

official supervising estate activities

Juan Carlos Moreno García of Université Charles-de-Gaulle wrote: “Texts inform us that the Hwt (administrative center) and especially the Hwt- aAt (literally “great Hwt”—administrative center, probably larger than the Hwt), were the most important royal production units in the country. The existence of networks of this sort, in which royal estates produced goods collected at administrative centers and subsequently redistributed to other localities or officials, has recently come to light at Elephantine: hundreds of seal inscriptions, mainly dating to the 3rd Dynasty, record the delivery of goods from Abydos, the most important supra-regional administrative center in southern Egypt, to the local representatives and officials of the king in service at Elephantine. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, Université Charles-de-Gaulle, France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Slightly later sources, from the beginning of the 4th Dynasty, also evoke an economic and production geography in which royal administrative centers like the Hwt and Hwt-aAt governed smaller localities, estates, and fields, as was the case according to Metjen’s inscriptions: many titles borne by this official show that the Hwt and Hwt-aAt were the heads of territorial and economic units, sometimes referred to as pr (houses/estates; plural: prw), that encompassed many localities (njwt; plural: njwwt) located mainly in Lower Egypt. “Therefore estates seem to have been firmly controlled by royal institutions and appear to have constituted the basic production units of the royal economy. The taxation and conscription of village inhabitants probably formed the other main source of income for the Pharaonic treasury, as the Gebelein papyri, from the end of the 4th Dynasty, show.

Temple Estates in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno García of Université Charles-de-Gaulle wrote: “Alongside the estates of the crown, temples too possessed important estates that provided the agricultural produce needed for offerings or for the support of personnel in charge of the cult. The Royal Annals mention estates granted by the king to cults and temples scattered throughout the country. The beneficiaries of these donations usually included the workers who cultivated the fields, as well as the storage and processing centers (pr-Sna) linked to the fields. The early- 5th-Dynasty inscriptions in the tomb of Nykaankh at Tihna el-Gebel provide insight into the organization of the economic activities of a provincial temple. The local sanctuary, dedicated to Hathor, had been granted a field of 0.5 hectares by 4th-Dynasty king Menkaura, a donation that was confirmed by Sahura at the beginning of the 5th Dynasty. Nykaankh and his family performed the required rituals and were accordingly paid with the produce of that field. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, Université Charles-de-Gaulle, France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Sources from the 6th Dynasty show that temples were important economic centers and that their estates were usually exploited by the local elite, who thus became integrated into the economic, social, and political networks controlled by the palace. Royal donations to local temples continued throughout the Old Kingdom, as is recorded in the recently discovered Royal Annals of the 6th Dynasty. At the same time, the pharaohs built royal chapels in the local sanctuaries and provided them with the economic means necessary for their construction: Iy-Mery of el-Hawawish in Upper Egypt, for example, proclaimed in his autobiographical inscription that he never took away the grain that was in his charge, except for that which constituted the payments relating to the works on the Hwt-kA chapel of Pepy at Akhmim. Titles and inscriptions concerning the royal Hwt-kA, and even their architectural remains at Tell Basta, reveal that they were present in many provinces of both Upper and Lower Egypt, very often inside the enclosure of an existing temple. Their construction suggests that the king intervened in the internal affairs of the temples and could control their economic activities, as is further evidenced by the decrees from Coptos.

“The most detailed sources concerning the foundation, organization, and exploitation of a temple domain are the royal decrees from the temple of Min at Coptos, dating from the 6th Dynasty. Two of these decrees refer to the organization of a new domain granted to the local god: first, the location was chosen from a piece of land comprising some fields that were inundated on an annual basis; then, a storage and processing center was created in order to administer the domain, organize its work force, and raise taxes; finally, the domain was divided into plots and placed under the supervision of an administrative council comprising local governors, the high priest of the temple, and some officials.

“The role of the local governors consisted of assembling the work force necessary to cultivate the fields. Other clauses of decrees D and G specified that the estates enjoyed temporary tax exemptions. Such estates formed the economic basis of the provincial temples, and the recent discovery of 6th- Dynasty clay tablets at Balat, in Dakhla Oasis, shows that this kind of economic organization existed even at a remote locality in the Western Desert, hundreds of kilometers from the Nile Valley.

“As for temples in proximity to the capital, two important archives found at the Abusir funerary complexes of 5th-Dynasty pharaohs Neferirkara and Raneferef cast some light on temple resources. It seems that the temples’ main sources of income were other temples, especially that of Ptah at Memphis, as well as several royal institutions. Some fragmentary papyri suggest that these temples also possessed their own estates, but the role played by the royal residence (Xnw) and the royal house (pr-nzwt) appears far more important in the provisioning of temples near Memphis. In fact, the Royal Annals and the administrative papyri from the Old Kingdom show that the transfer of resources from the royal sphere to the temples was a well- established practice during the Old Kingdom. The titles borne by the officials of el- Hawawish also suggest that the crown transferred some estates to the local temple of Min. These measures do not imply, however, that the crown was losing resources and power for the benefit of the temples. The occasional tax exemptions granted to temples were temporary and revocable, and inscriptions like that of 6th-Dynasty official Harkhuf of Elephantine proclaim that both the temples and the royal estates formed networks where food and products were stored and kept at the disposal of the royal agents. The decrees of Coptos also enumerate the officials and the royal departments that usually requisitioned workers and taxes from the temples.”

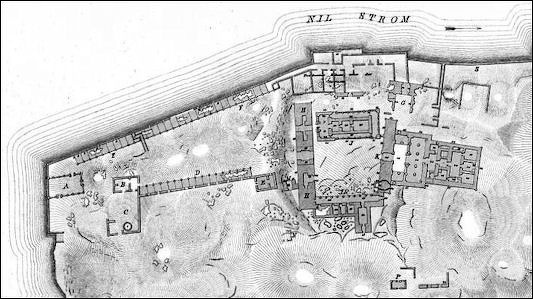

Isis Temple

Estates and Local Officials in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno García of Université Charles-de-Gaulle wrote: “A third kind of domain was formed by the landed possessions held by royal officials as remuneration for their services. Little is known about the standard estates allotted to each category of official (the categories having been based on an individual’s rank, function, and status). [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, Université Charles-de-Gaulle, France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Some agents of the king boasted in their autobiographical inscriptions of the (presumably exceptional) estates granted to them by the king to reward them for their outstanding services: Metjen (4th Dynasty) was rewarded with fields of variable dimensions for his activities as governor of several royal administrative centers (Hwt and Hwt-aAt) in Lower Egypt; Sabni of Elephantine (6th Dynasty) was nominated as xntj-S (an honorific court title) of a royal pyramid and was granted a field of about eleven hectares after a successful mission in Nubia; and Ibi of Deir el-Gabrawy (6th Dynasty) received a field of about fifty hectares linked to a Hwt. It seems doubtful whether the descendants of an official could have inherited the estates granted in this way. Members of the royal family (especially the royal sons) were possibly an exception, as their property was administered by a special administrative branch: the Overseer of the Provinces of Upper Egypt Kapuptah (5th Dynasty), for example, was also Overseer of the Property of the Royal Sons in the Provinces of Upper Egypt (jmj-r jxt msw nzwt m zpAwt Smaw), whereas Ankhshepseskaf (5th Dynasty) was Overseer of the Estates of the Royal Sons (jmj-r prw msw nzwt), a title also borne by his contemporary, the vizier Senedjemib-Inti; and prince Nykaura, a son of pharaoh Khafra, distributed his many estates among his wife and children while he was alive, although it is not certain that his instructions were also valid after his death. Some royal decrees, as well as the papyri from the royal funerary complexes of Neferirkara and Raneferef, show that the nomination of an official as xntj-S of a royal pyramid was an important source of income that included both offerings and agricultural estates. But access to these coveted honors was restricted, as the decrees in the Raneferef archive proclaim.

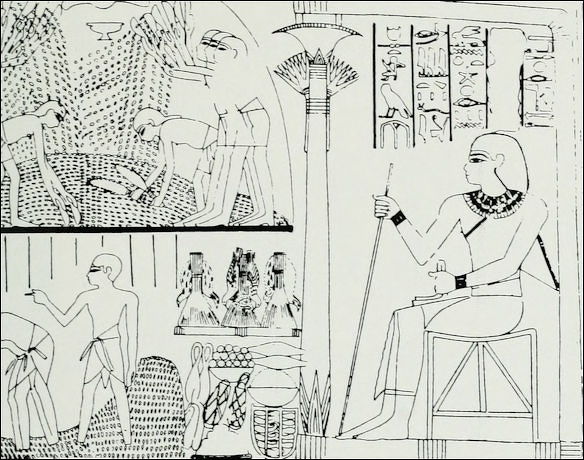

“The granting of estates as remuneration or reward to the officials of the kingdom was so widespread that an iconographic motif arose in private tombs depicting processions of offering bearers accompanied by place-names that supposedly represented the estates possessed by the tomb owner. However, these place-names seem to have been for the most part fictitious, used mainly as a decorative device emulating the ideal landscape governed by the king, a landscape represented in the funerary monuments of the king himself: the precisely symmetrical depiction of estates on the walls of the tombs (even in cases where the offering bearers bore no name), the absence of any information about virtually all these alleged place-names (even in the tombs of the heirs of the original owners), and the representation of exactly the same number of estates in both Upper and Lower Egypt suggest that this iconographic motif was not intended to depict the estates actually granted to an official.”

Land Tenure in Ancient Egypt

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “Land tenure describes the regime by means of which land is owned or possessed, whether by landholders, private owners, tenants, sub-lessees, or squatters. It embraces individual or group rights to occupy and/or use the land, the social relationships that may be identified among the rural population, and the converging influences of the local and central power structures. Features in the portrait of ancient Egyptian land tenure that may be traced over time in response to changing configurations of government include state and institutional landownership, private smallholdings, compulsory labor (corvée), cleruchies, leasing, and tenancy. Such documents as Papyrus Harris I, the Wilbour Papyrus, Papyrus Reinhardt, and the Ptolemaic Zenon and Menches archives provide evidence of various regimes of landholding, the status of the landholders, their relationship to the land, and the way in which the harvest was divided among cultivators, landowners, and the state. Ptolemaic leases and conveyances of land represent the perspective of individual landowners and tenants. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

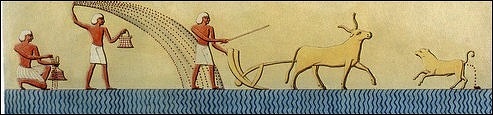

“The division of Egypt into two distinct agricultural zones, the 700-km-long Nile Valley and the Delta, as well as the Fayum depression and the oases of the Western Desert, produced regional differences that caused considerable variation in the organization of agriculture and the character of land tenure throughout antiquity. The village-based peasant society worked the land under a multiplicity of land tenure regimes, from private smallholdings to large estates employing compulsory (corvée) labor or tenant farmers under the management of the elite, temples, or the Crown. However cultivation was organized, it was predicated on the idea that the successful exploitation of land was the source of extraordinary power and wealth and that reciprocity, the basis of feudalism, was the key to prosperity.

“Consistent features in the mosaic of land tenure were state and institutional landowners, private smallholders, corvée labor, and cleruchs, the importance of any single feature varying over time and from place to place in response to changing degrees of state control. Leasing and tenancy are also elements that pervade all periods with varying terms as revealed by surviving leases. The importance of smallholding is to be emphasized since even large estates consisted of small plots as the basic agricultural unit in a system characterized by competing claims for the harvest. However, the exact nature of private smallholding in Pharaonic Egypt is still under discussion as is clear from studies that explore local identity and solidarity in all periods, subject to regional variation; the conflict between strong assertions of central control in the capital and equally powerful assertions of regional individuality and independence in the rural countryside; and the dislocation of the villager and his representatives from the local elites. Land tenure was also affected by local variation in the natural ecology of the Nile Valley. Moreover, variations in the height of the Nile over the medium and long term directly affected the amount of land that could be farmed, the size of the population that could be supported, and the type of crops that could be sown.

“The alternation of periods of unity and fragmentation in the control of the land was a major determinant of the varieties of land tenure that came to characterize the ancient Egyptian economy. The disruption in the balance between strong central control and local assertions of independence that resulted in periods of general political fragmentation or “native revolts” had a powerful effect upon the agrarian regime, economy, and society.

“The state’s collection of revenues from cultivated land under various land tenure regimes is also an element of continuity since the resources of the land constituted the primary tax-base for the state. Cultivators of all types had to cope with the payment of harvest dues owing to the state under all economic conditions, from famine to prosperity. These revenues fall under the terms Smw and SAyt and perhaps other terms occurring in economic and administrative texts in reference to dues owing to the state from the fields of the rural countryside.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Land Tenure (to the End of the Ptolemaic Period) by Sally Katary escholarship.org

Land Tenure in the Predynastic Period and Old Kingdom (3100-2150 B.C.)

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “Landholding initially occurred within the confines of the village economy and likely produced no more than a subsistence existence. There was, however, in the Predynastic Period a network of trade bases, settlements, and administrative centers that contributed to government control over limited areas, facilitated trade, and shaped the spatial organization of the landscape. With the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt c. 3100 B.C. and the establishment of a national capital at Memphis, and its concomitant infrastructure for the administration of agricultural production, large royal estates came into being. Royal institutions known as the Hwt (a kind of royal farm) and the Hwt aAt (great Hwt) became centers of royal power and institutional agriculture in the countryside serving several purposes, including the warehousing of agricultural goods, as well as their administration and defense. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Private ownership in the Old Kingdom traces back to land-grants to members of the king’s immediate family and eventually to more distant relatives, as well as officials. The desire to secure the personal disposal of landed property for families was eventually achieved by the establishment of permanent mortuary endowments, in which family members carried out the responsibilities of the cult in exchange for a share in the revenue of the lands that comprised the endowment. These offices became hereditary and brought with them the right to a share in the foundation’s property.

“Old Kingdom tomb biographies of the elite provide the earliest detailed knowledge of landholding. The autobiography of Metjen, controller of vast Delta estates under Third Dynasty king Djoser, provides the earliest example of private landholding. While Metjen’s power base was the Delta, he also enjoyed authority over two Upper Egyptian nomes, controlling landholdings and the wealth derived from them as an official of the king. This valuable property consisted of 266 arouras (1 aroura = 0.66 acre) plus a small vineyard, an estate in keeping with the grandeur of his Saqqara tomb. Metjen’s titles, including HoA-aHt, are testimony to the prominence of the institutional aHt-land at this early date and of the royal agricultural centers, the Hwt and the Hwt aAt, in the rural areas, as well as to the establishment of other agricultural units or types of royal settlement known as grgt and aHt. Moreover, Metjen was the chief of wab-priests and, as such, participated in the improvement of the cultivable land. Elite officials such as Metjen cultivated their large properties through the agency of supervised compulsory (corvée) laborers called mrwt. Metjen bore personal responsibility for the operations and productivity of the lands entrusted to him and the flow of revenues from the land to the authorities who had a claim upon them.

“Temples took on a more conspicuous role in the rural landscape during the Fifth Dynasty, just as the role of provincial governors or nomarchs (HAtj-a) was also on the ascendant. According to an inscription at his early Fifth Dynasty tomb at Tehneh in Middle Egypt, Nikaankh, Keeper of the King’s Property and Steward of the Great Domain, had control of the royal agricultural centers in his province. He was made Chief Priest of the Temple of Hathor, Lady of Ra-Inet by king Userkaf, with responsibility for temple income. Nikaankh was entitled to bequeath the two arouras in endowments he had received in the reign of Menkaura for cult service to his sons who succeeded him in his offices in the cult of Hathor, and a private mortuary cult, provided they continued their service faithfully and the property was kept intact.

“According to the royal annals of the Palermo Stone, kings frequently granted provincial temples donations of land, from royal pastures and riparian land, together with workers and processing centers. These donations, especially when large, were significant events in any pharaoh’s reign. Especially noteworthy was the donation to the god Ra of at least 1704 arouras and 87 cubits (459.7 hectares) in the Fifth Dynasty—an extremely generous, in fact unsurpassed, donation for the times. Most frequently, the donations were located in Lower Egypt, where there was great potential for agricultural development.

“In the royal pyramid cities, smallholders called xntjw-S were often able to develop their holdings into profitable estates. These smallholders had roles in the cult and served the estate of the funerary institution, enjoying access to endowment land and royal exemption from the corvée or any unlawful seizure. The exemption decree enacted by Pepy I on behalf of the pyramid town of Seneferu at Dahshur restricted the cultivation of fields belonging to a pyramid town to the xntjw-S of that town. The mrwt of any elite party or official were forbidden to cultivate those holdings. This protected the status of the xntjw-S as small farmers with an elevated standing among the peasantry.

“Changes to the agricultural landscape at the end of the Old Kingdom derived in part from the increasing power struggle between the central government and the provincial nobility. The Hwt went into decline at the end of the second millennium B.C. as new concepts of the spAt (district, nome) and njwt (city, town) came into play. When the reorganization of the state was achieved with the Eleventh Dynasty, a new system replaced the old network of the Hwt.”

Land Tenure in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.)

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “When pharaohs from a Theban line of princes stabilized the country from north to south, they ended the political, social, and economic fragmentation of the First Intermediate Period and reunited Upper and Lower Egypt in a regime that allowed the orderly management of the land and its resources. The Eleventh Dynasty was followed by the Middle Kingdom, a new period of cultural flowering in which a “middle class” came into increasing importance in the land tenure regime. According to Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446, by the Middle Kingdom, royal agricultural units (wart) administered lands described as xbsw, “plowlands,” likely cultivated by corvée labor organized into work teams through conscription. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Temples controlled vast holdings of aHt-lands for cultivation under wab-priests responsible for the payment of taxes as described in the Instructions for Merikara and documented in the Lahun archives. These priests, along with xrpw (agents/administrators), were intermediaries between the peasant producers and the temple administration, paying large quantities of grain as income to the temples. The agricultural model we detect in the Lahun archives, in which temples administered cultivable land, greatly resembles that of the Old Kingdom.

“During the Middle Kingdom, smallholders cultivated Sdw- fields and were relatively independent. The correspondence of the Twelfth Dynasty kA- priest (mortuary priest) and farmer Hekanakht regarding the operation of the family’s farm properties, south of Thebes, is crucial here. Although family-run, Hekanakht’s farm properties were dispersed over a number of villages rather than centrally located. The farms were a joint, extended-family enterprise: the father and sons made decisions on both the crop and required labor. Family members were assisted in the operations by wage- laborers who became the family’s dependents. Capital from the work of weavers and a herd of thirty-five cattle supplemented the farm income. The letters give the impression of an autonomous economic life, free of interference by any outside system or authority, even though Hekanakht certainly functioned within the constraints of an economic system that he shrewdly manipulated to his best possible advantage.

“Hekanakht, the kA-priest turned entrepreneur, acquired his landholdings through inheritance, purchase, in payment of a debt, and/or as remuneration for services rendered. It is likely that some of his property was endowment land since, as a kA-priest, his labor would have been rewarded with a land grant that provided the right to use the land in perpetuity. The regular payment of taxes on his land guaranteed Hekanakht’s freedom to cultivate it exactly as he wished. The occurrence of the word odb, “to rent,” in Letter I, 3 - 9 is evidence of Hekanakht’s leasing of land through the payment of a share of the crop or various commodities (copper, cloth, barley). Well-capitalized family farms such as those of Hekanakht provided an efficient form of agriculture.

“The Twelfth Dynasty tomb inscription of Hapdjefa (I) of Assiut, a high priest of Wepwawet and of Anubis, and a nomarch (HAtj-a) in the reign of Senusret I, provides crucial data on income from landed property. It very clearly demarcates between lands and their income that Hapdjefa possessed by virtue of his official roles, and income, consisting of lands, tenants, and cattle, he inherited as a private individual from his paternal estate. The latter properties were alienable, while the former were not. As nomarch, Hapdjefa inherited from his predecessors lands, as well as the temple offerings that went with the office and would be inherited by the next nomarch. As high priest, Hapdjefa was paid in kind for his services, but these payments occurred only during his tenure. He had no right to alienate any of the properties of the cult or to benefit from them or their income during his lifetime. What he did with his patriarchal inheritance was, however, up to him as we learn from a series of ten contracts that relate to the establishment of a pious foundation on behalf of his cult statues.”

Land Tenure in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.)

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “New Kingdom pharaohs regularly rewarded high achievers land in recognition of their service to the state. According to the inscriptions from his tomb at Elkab, the crew commander Ahmose son of Abana received extensive estates, including one comprising 60 arouras in Hadja, as “favors” of the king. Five arouras of land were located in his hometown of Elkab as was customary in the case of veterans being rewarded for service to king and country. In addition, Ahmose received both male and female slaves (Hm, Hmt), some of whom may have worked his land. Since by the end of Ahmose’s life, his estates would likely have been widely dispersed geographically, and the family probably preferred to reside comfortably in town, slaves or local cultivators would have worked distant holdings as individual income- producing units. Shares (psSt) in the cleruch’s holding would be inherited, generation to generation, and this would reinforce the relationship between the state and the heirs in a land tenure pattern that would shape the New Kingdom economy. As veterans entered into the agricultural economy as landholders, the stage was set for an increased involvement of the military in landholding that would reach its fullest expression in the Ptolemaic cleruchy. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The Wilbour Papyrus is our most valuable and extensive Pharaonic document for regimes of land tenure. It details the assessment of both private smallholdings and large, collectively cultivated domains in Middle Egypt, administered by temples and secular institutions in year four of Ramesses V. The importance of the Wilbour Papyrus is that it elucidates the administration of cultivable land by temples and secular institutions in cooperation with the state, while raising important questions about the relationship between temples, the state, and the cultivators that are still not easily answered.

“While the precise purpose and context of the Wilbour Papyrus is still unclear, the document may have been an archive copy of the field survey ordered by the aA n St, “Chief Taxing Master,” responsible for temple finance. The limited extent of the agricultural holdings recorded in Wilbour (approximately 17,324 arouras = 4674 hectares) led one scholar to speculate that it was the jpw-register of Amun —that is, the (comprehensive) land survey document of the House of Amun. The abundance of towns and villages in the measurement lines of both Text A and Text B, identifying the locations of plots, reflects the underlying hierarchies of towns and villages as the fundamental units of agricultural organization. The lack of specificity in the location of the plots of smallholders perhaps argues in favor of the smallholdings representing individual right of access to land and the right to profit by its exploitation rather than “ownership” per se.

“Smallholders of all occupations cultivated heritable plots, most often three or five arouras in size, on institutional “apportioning domains,” a plot of five arouras supporting a family of some eight persons. These private possessors paid dues on a tiny portion of their fields at a nominal fixed rate. Whether this extremely small amount represents a tax (Smw) or a management fee to the temple on whose land the plot was situated is difficult to say.”

Temples and Land Tenure in New Kingdom Egypt

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “While real estate was granted to individuals by the state, individuals also turned property over to the management of temple estates by means of funerary endowments. The endowment of Si- mut, called Kyky, scribe and inspector of cattle in the stalls of Amun in the reign of Ramesses II, exemplifies the custom of the donation of personal property to temples by individuals who entered into contracts with temples for the deity’s protection. Si-mut’s act of endowment comprises a long inscription covering three walls of his Theban tomb and summarizes a legal contract. Not having any children or siblings to care for him in his old age and organize his funeral and mortuary cult, Si-mut donated all his worldly goods to the temple of Mut, likely in return for a pension that would enable him to live out the remainder of his days comfortably, secure in the knowledge that his obsequies would be carried out by the temple. Unfortunately, the lower part of the inscription that contains details concerning the endowment is poorly preserved. Nevertheless, it was by such benefactions that temples gained control over even more property, and more distant relations of the donor were excluded from any possibility of inheriting from the estate. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Papyrus Harris I attests the preponderant role of the temples as distinct economic entities in their own right, with authority over cultivation and landholding. This royal document enumerates the land- wealth of the temples of Amun, Ra, Ptah, and smaller less well-known temples: a total of 1,071,780 arouras, comprising some 13 to 18 percent of the available cultivable land. It is very likely that the temple holdings enumerated here were donations made by Ramesses III, with priority going to his own mortuary temple at Medinet Habu.

“Papyrus Harris I supports the idea that temples were an integral part of the state, yet not a branch or department of the state administration, providing legitimacy to the government in exchange for which the king granted them all necessities and then some. The separate but interlinked bureaucracies of temples and government assured the temples control of their own production but made it possible for the government freely to remit part of its own wealth to the temples. Temples commanded the labor of large numbers of royal subjects to till the land in various arrangements the temples themselves controlled. The cultivators of temple lands were themselves taxed by the state to provide for the temples, thus completing the circle that, in theory at least, connected temples, populace, and the state in a mutually beneficial relationship.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024