WORKERS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

grinding grain

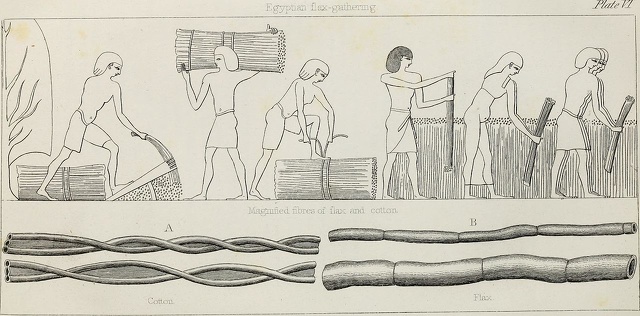

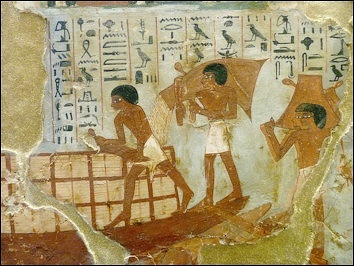

As agriculture became more advanced, surpluses were generated, freeing farmers to perform other jobs. Over time former farmers could earn enough to specialize in certain tasks and become what would qualify as craftsmen. Organized labor was also needed to build other structures, quarry stone, mine precious metals and stones and build and maintain irrigation canals and other water projects. The Egyptians built many canals and irrigations systems. They didn't make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. The Egyptian economy in the time of the pyramids was powered the by the construction of the pyramids. Pyramids building required labor. An economy was necessary to pay them.

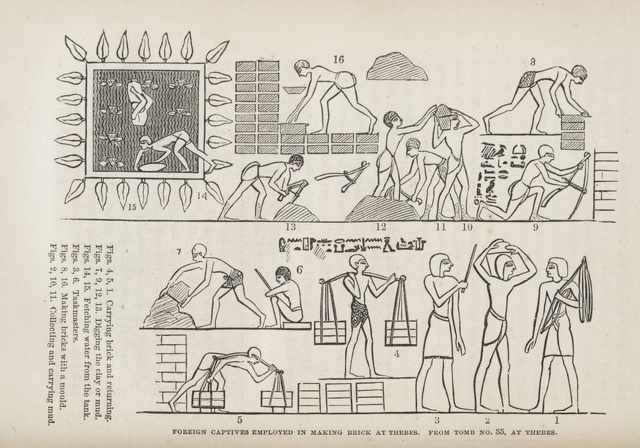

For much of the year it seems that most people in ancient Egypt were involved in agricultural activity of some kind, but during the flood (July- In ancient Egypt there was paid labor (usually through rations), corvée compulsory labor and slavery. In addition there were farmers, at least some of whom were also workers during the season when there was not much agricultural work to do. Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “An income strategy different from subsistence was labor, either voluntary or compulsory. Compulsory labor is known from ancient Egypt in two forms: corvée and slavery. Corvée (bH) is well attested as periodical compulsory labor (especially in earlier periods), and everyone but the highest functionaries could be subjected to it. In the Old Kingdom, groups of workers subject to this practice were called mrt and worked in agricultural domains founded by the government . The same word mrt was used for the personnel of temple workshops in the New Kingdom; these were often prisoners taken during military campaigns. In the Middle Kingdom, temporary compulsory labor on state fields was controlled by the xnrt (interpreted as "labor camp" by Quirke). Even the nmH(y) of the New Kingdom (see Institutional and Private Interests above) could be summoned for service to government officials, as becomes clear from the decree of King Horemheb.” [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Among those that worked in trades and professions in ancient Egyptian were: barbers, potters, arrow makers, merchants, basket makers, record keepers, tool and weapons makers, goldsmiths, silversmiths, butchers, stonemasons, water carriers, fishermen, estate workers, farmers, tanners, weavers, boatbuilders, furniture makers, bakers, metal workers, pottery makers, beer brewers, bread makers, leatherworkers, spinners, weavers, clothes makers and jewelers. Many craftsmen and artisans were employed by the state and nobles. Their shops and workshops were often set up near the palaces of the pharaohs, aristocrats or high officials. Their crafts tended to be passed on from one generation to the next

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“'Make it According to Plan': Workshop Scenes in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom” by Michelle Hampson (2022) Amazon.com;

”The Production, Use and Importance of Flint Tools in the Archaic Period and the Old Kingdom in Egypt” by Michał Kobusiewicz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: Ground Stone Tools, Rock-cut Installations and Stone Vessels from Prehistory to Late Antiquity” by Andrea Squitieri and David Eitam (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Use of the Potter’s Wheel in Ancient Egypt” by Sarah Doherty (2015) Amazon.com;

”A Manual of Egyptian Pottery, Volume 1: Fayum A - A Lower Egyptian Culture”

by Anna Wodzinska (2011) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Metalworking and Tools” by Bernd Scheel (1999) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Worker’s Village of Amarna

Deir el-Medina

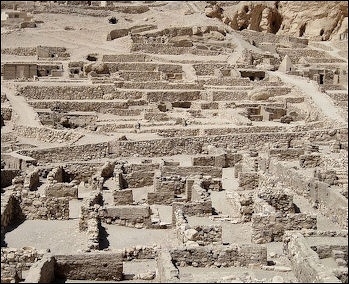

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The village is one of few housing areas at Amarna to have been formally planned: it is laid out with rows of 73 equally sized house plots, and one larger house, all surrounded by a perimeter wall around 80 centimeters thick with two entranceways. Apart from the larger house, thought to belong to an overseer, the village houses exhibit at ground-floor level a tripartite plan not generally found in the riverside suburbs, with a staircase leading to a roof or further s tory/s above . Perhaps quite soon after the village was founded, its occupants modified and added to their houses and settled the land outside the village walls, constructing chapels, tombs, animal pens, and garden plots. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The latter reflect the efforts of the villagers themselves to sustain their community, but the isolated location of the site, and lack of a well, also made it dependent on supplies from outside. An area of jar stands known as the Zir Area on the route into the village seems to represent the standing stock of water for the village, supplied by deliveries from the riverside city, the route of which is still marked by a spread of broken pottery vessels (Site X2). Near the end of the sherd trail there is a small building (Site X1), which may be a checkpoint connected with the importation of commodities.

“Given its location and similarity to the tomb workers’ village at Deir el-Medina, the Workmen’s Village is thought to have housed workers, and their families, who cut and decorated the rock-cut tombs, including those in the Royal Wadi. This identification is supported by the discovery at the site of a statue base mentioning a “Servant in the Place,” recalling the name “Place of Truth ” used by the tomb-cutters at Deir el-Medina.

“The internal history of the village, however, is not easy to reconstruct. At some stage an extension was added to the walled settlement, possibly to accommodate a growing workforce to help complete the royal tombs. It has also been suggested that, perhaps late in its occupation, the site housed a policing unit. Excavations have produced a relatively high proportion of jar labels and faience jewelry from the last years of the reign of Akhenaten and those of his successors, suggesting a burgeoning of activity at this time, but without ruling out earli er occupation. The discovery of a 19 th Dynasty coffin beside the Main Chapel indicates that the village site was still known of later in the New Kingdom.”

Substitute Workers in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Interestingly, Old Kingdom lists of personnel frequently state that workers were actually replaced by their wives, fathers, brothers, sons, or daughters, or by other persons. Middle Kingdom papyri from Lahun confirm this practice: in one case the names of several workers were accompanied by annotations specifying that they should be brought in person or replaced by their wives, mothers, or Asiatics (serfs?) ; in another case, a governor requested two workers or, in their place, men or women from among their own dependants; finally, another papyrus not only listed a labor force but also identified the persons (usually priests and officials) for whom the worker answered the call. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Sometimes, workers recruited on a local basis came from the households (pr) and districts (rmny) of provincial potentates. New Kingdom sources also mention tenants acting as agents of scribes . At a higher social level, clients or colleagues were expected to replace their “patrons” when performing ritual services in the temples. In exchange for their services, the superior was expected to take care of his subjects. Such bonds linking clients and subordinates to their patron’s household were significantly marked by the use of kinship terms.

“Thus, compulsory workers were sometimes described as the “sons” of prominent citizens: “N, he is called the son of Senbebu, a priest of Thinis,” “N, he is called the son of Hepu, a commander of soldiers [of This]” (Hayes 1955: 25 - 26), while palatial officials were explicitly labeled as “friends” (xnms.f) or “(pseudo-)children” (Xrd.f) of their superior. More clearly, the patron-client relationship was sometimes formalized by means of legal contracts, even by fictitious adoptions that masked what constituted, in fact, the voluntary servitude of the person called Srj “son”. Lastly, vertical integration often implied that someone was the client or subordinate of another person who, in turn, proved to be the client of a third individual.

Work Gangs in Ancient Egypt

To each of the great departments in Egypt belonged artisans and laborers, who were divided into “companies. " We meet with one of these companies in the domains of the rich proprietors of the Old Empire, headed by their banner-bearer and reviewed by the great lord. The rowers of each great ship formed a company. The workmen of the temple and of the necropolis were organised in the same way. When speaking of an individual workman, the name of the chief under whom he worked was usually added and that of the department to which he belonged: “the workman Userchopesh, under the chief workman Nakhtemhet of the Necropolis." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

At the head of each company of workmen stood the chief workman, who bore the title of" Chief of the Company”; he was not very much above his people, for we have an instance of a man, who in one place is designated simply as a "workman," and in another more precisely as “chief workman. "' He was nevertheless proud of his position and endeavored, like the higher officials, to bequeath his office to one of his sons. ' He carefully kept notes in a book about their diligence. On a rough tablet of chalk in the British Museum “a chief workman has written down the names of his forty-three workmen and, by each name, the days of the month on which the man failed to appear.

Many were of exemplary industry, and rarely missed a day throughout the year; less confidence could be placed in others, who failed more than a fortnight. Numberless are the excuses for the missing days, which the chief workman has written down in red ink; the commonest is of course ill, in a few instances we find lasy noted down. A few workmen are pious and “are sacrificing to the god”; sometimes a slight indisposition of wife or daughter is considered a valid reason for neglect of work.

We have some exact details about the conduct of a company of workmen, who were employed in the City of the Dead at Thebes, in the time of Ramses IX. We do not know precisely what their employment was, but they seem to have been metalworkers, carpenters, and similar craftsmen. Their chief kept a book with great care, and entered everything remarkable that happened to his company during the half-year. He noted each day whether the men had “worked “or had been “idle. " For two full months (from the 5th of Phamenoth to the 11th of Pachons) no work was required, though by permission the time was registered as working days; during the next two months also half the time was kept as a festival. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Typically a workman had his wife, or more frequently a friend who lived with him as his wife; he had his own house, sometimes indeed situated in the barren necropolis, and often he even had his own tomb. He was educated to a certain degree, as a rule he could read and write, and when speaking to his superiors, he frequently expressed himself in high-flown poetic language. At the sametime we cannot deny that his written attempts are badly expressed and present an inextricable confusion of sentences.

Rations for Workmen in the City of the Dead in Thebes

Workmen in the City of the Dead in Thebes received their rations each day whether they worked or not. Four times in the month they seem to have received from different officials a larger allowance (perhaps 200-300 kilograms) of fish, which appears to have formed their chief food. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Each month they also received a portion of some pulse vegetable, and a number oi jugs, which may have contained oil and beer, also some fuel and some grain. With regard however to the latter there is a story to tell. It is one of the acknowledged characteristics of modern Egypt that payments can never be made without delays, so also in old Egypt the same routine seems to have been followed with respect to the payments in kind.

The letters and the documents of the officials of the New Kingdom are full of complaints, and if geese and bread were only given out to the scribes after many complaints and appeals, we may be sure that still less consideration was shown to the workmen. The supply of grain was due to our company on the 28th of each month; in the month of Phamenoth it was delivered one day late, in Pharmuthi it was not delivered at all, and the workmen therefore went on strike, or, as the Egyptians expressed it, "stayed in their homes. "

On the 28th of Pachons the grain was paid in full, but on the 28th of Payni no grain was forthcoming and only 100 pieces of wood were supplied. The workmen then lost patience, they “set to work," and went in a body to Thebes. On the following day they appeared before “the great princes “and “the chief prophets of Amun," and made their complaint. The result was that on the 30th the great princes ordered the scribe Chaemucse to appear before them, and said to him: “Here is the grain belonging to the government, give out of it the grain-rations to the people of the necropolis. " Thus the evil was remedied, and at the end of the month the journal of the workman's company contains this notice: “We received to-day our grain-rations; we gave two boxes and a writing-tablet to the fan-bcarcr. " It is easy to understand the meaning of the last sentence; the boxes and the writingtablet were given as a present to an attendant of the governor, who persuaded his master to attend to the claims of the workmen.

Poor Working Conditions and Strikes at the City of the Dead in Thebes

The condition of the workmen of the necropolis was just as deplorable in the 29th year of Ramses III ; they were almost always obliged to enforce the payment of every supply of the food owing to them by a strike of work. On these occasions they left the City of the Dead with their wives and children, and threatened never to return unless their demands were granted. Documents have come down to us showing that at this time the sad state of things went on for half a year. The month Tybi passed without the people receiving their supplies; they seem to have been accustomed to such treatment, for they waited full nine days before again pushing affairs to extremities. They then lost patience, and on the 10th of Mechir “they crossed the five walls of the necropolis and said: ' We have been starving for 1 8 days: ' they placed themselves behind the temple of Thutmose III. " In vain the scribes of the necropolis and the two chiefs of the workmen tried to entice them back by “great oaths," the workmen were wise and remained outside. The next day they proceeded further, even as far as the gate at the southern corner of the temple of Ramses II ; on the third day they even penetrated into the building. The affair assumed a threatening aspect, and on that day two officers of the police were sent to the place. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The priests also tried to pacify the workmen, but their answer was: “We have been driven here by hunger and thirst; we have no clothes, we have no oil, we have no food. Write to our lord the Pharaoh on the subject, and write to the governor who is over us, that they may give us something for our sustenance. " Their efforts were successful: “on that day they received the provision for the month Tybi. " On the 13th of Mechir they went back into the necropolis with their wives and children. Peace was re-established, but did not last long; in fact only a month. Again in Phamenoth the workmen crossed the wall of the City of the Dead, and driven by Jmugcr they approached the gate of the town. Here the governor treated with them in person; he asked them (if I understand rightly) what he could give them when the storehouses were empty; at the same time he ordered half at least of the rations that were overdue to be paid down to them.

In the month of Pharmuthi the supplies seem to have been duly given out, for our documents mention no revolt; but in Pachon the workmen suffered again from want. On the second day of the latter month two bags of spelt were remitted as the supply for the whole month; we cannot be surprised at their resenting this reduction in their payment, and at their resolution to go down themselves to the grain warehouse in the harbour. They only got as far as the first wall of the City of the Dead; there the scribe AmenNakhtu assured them he would give them the rest of the spelt if they remained quiet; they were credulous enough to return. Naturally they did not receive their grain now any more than before, and they were obliged again to “cross the walls," after which the “princes of the town “interfered, and on the 13th of the month ordered fifty sacks of spelt to be given to them.

Workers on the Move in Ancient Egypt

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “Apart from members of expeditions and of the army, other travelers with a variety of occupations are mentioned in the texts. Egyptian physicians not only took part in expeditions, but they were sent out by the pharaoh on building projects and to foreign royal courts, due to the considerable repute they enjoyed. [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Architects were on the move for professional reasons and on behalf of the pharaoh to supervise official building projects. One such architect was Nekhebu of the 6th Dynasty. He was sent out several times by Pepy I to Upper and Lower Egypt to oversee the digging of a canal in Qus and the royal building projects in Heliopolis, where he stayed for six years. During this time, he made a few official trips to the residence in Memphis.

“The mobility of scribes arose from the fact that, being part of the bureaucracy, they were transferred by official order to new places of employment as required. This could be sent within Egypt but abroad as well. Such a widely traveled scribe was Nebnetjeru, whose graffiti is found between Kalabsha and Dendur, near Tonkalah, and possibly even at Toshka.

“Craftsmen were also on the move. There is evidence of craftsmen in the service of private individuals and of pharaoh. They were not necessarily tied to a particular workshop but were sent out on expeditions and large-scale royal building projects. Even higher-ranking craftsmen with titles such as Hmw wr, jmj-rA kAt, and jmj-rA nbjw n pr Ra are among those whose project-related work orders caused them to travel.

“Priests traveled not only as members of expeditions but also in order to fulfil special duties for temples or to organize religious festivities, as did Ikhernofret at Abydos in the 12th Dynasty. A high official’s occupational move to a different location is frequently mentioned. Mayors , viziers, as well as the pharaoh traveled on official government business—e.g., inspections, and diplomatic or military missions. Royal journeys are shown to have taken place beginning in Predynastic times from several sources including annals. Furthermore, the so-called Smsw 1rw, the “following of Horus,” took place every two years and led the king through the whole land . In the New Kingdom, Pharaoh traveled yearly for religious reasons to Thebes to celebrate the Opet Festival. Royal travels are further attested in the annals of Thutmose III reporting his war campaigns or the inscriptions at the temple of Kanais recording a visit by Sety I to the Eastern Desert.”

Ancient Egyptian Workers Got Paid Sick Leave

Anne Austin wrote in the Washington Post: Among the texts found at Deir el-Medina, a village of artisans near the Valley of the Kings, “are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from their jobs. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workers were paid even if they were out sick for several days. [Source: Anne Austin, Washington Post, February 17 2015. Anne Austin is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University ***]

“These texts also identify a workman on the crew designated as the swnw, physician. The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. The Egyptian state even gave the physician extra rations as payment for his services to the community of Deir el-Medina. This physician would have most likely treated the workers with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus. About a dozen extensive medical papyri have been identified from ancient Egypt, including one set from Deir el-Medina. ***

“These texts were a kind of reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for a variety of ailments. The longest of these, Papyrus Ebers, contains more than 800 treatments covering anything from eye problems to digestive disorders. As an example, one treatment for intestinal worms requires the physician to cook the cores of dates and colocynth, a desert plant, together in sweet beer. He then sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days. ***

“Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items such as honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers. ***

“Despite paid sick leave, medical rations and a state-supported physician, it is clear that in some cases the workmen were actually laboring through their illnesses. For example, in one text, the workman Merysekhmet attempted to go to work after being sick. The text tells us that he descended to the King’s Tomb on two consecutive days, but was unable to work. He then hiked back to Deir el-Medina where he stayed for the next 10 days until he was able to work again. Although short, these hikes were steep: The trip from Deir el-Medina to the royal tomb involved an ascent greater than climbing to the top of the Great Pyramid. Merysekhmet’s movements across the Theban valleys probably were at the expense of his health. This suggests that sick days and medical care were not magnanimous gestures of the Egyptian state, but rather calculated health-care provisions designed to ensure that men like Merysekhmet were healthy enough to work.” ***

Bad Workers in Ancient Egypt

There were some bad apples among ancient Egyptian workers. The chief workman Paneb'e, under King Seti II, must have been exceptionally bad. He stole everything that came in his way: the wine for the libations, a strap from a carriage, and a valuable block of stone; the latter was found in his house, although he had sworn that he had not got it. Once he stole a tool for breaking stones, and when, after searching for it vainly for two months, "they said to him: ' It is not there,' he brought it back and hid it behind a great stone. . . . When he stationed men to cut stones on the roof of the building of King Seti II, they stole some stone every day for his tomb, and he placed four pillars of this stone in his tomb. " In other ways also he provided cheaply for the equipment of his tomb, and for this object he stole “two great books “from a certain Paherbeku, doubtless containing chapters from the Book of the Dead. He was not ashamed even to clear out the tomb of one of his subordinates. “He went down into the tomb of the workman Nakhtmin, and stole the couch on which he lay. He also took the various objects, which are usually provided for the deceased, and stole them. " Even the tools which he used for the work of his tomb were royal property. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

He continually turned his workmen to account in various ways for private purposes: once he lent them to an official of the temple of Amun, who was in need of field laborers; he commissioned a certain Nebnofr to feed his oxen morning and evening, and he made the wives of the workmen weave for him. He was also charged with extortions of all kinds, especially from the wives and daughters of his workmen. He was guilty also of cruelty: once he had some men soundly tortured in the night; he then took refuge on the top of a wall, and threw bricks at them.

The worst of all was his conduct to the family of the chief workman Nebnofr. While the latter was alive, he seems to have lived in enmity with him, and after his death, he transferred his hatred to the two sons, especially to Neferhotep, who succeeded his father in his office. He even made an attempt on his life. “It came to pass that he ran after the chief workman Neferhotep . . . the doors were shut against him, but he took up a stone and broke open the door, and they caused people to guard Neferhotep, for Paneb'e had said that he would in truth kill him in the night; in that night he had nine people flogged, and the chief workman Neferhotep reported it to the governor Amenmose and he punished him. " Paneb'e. however, extricated himself from this affair, and finally he seems to have made away with Neferhotep; notwithstanding this he appears to ha\e lived on in peace, because, if we may believe the accusaticMis against him, he killed those who could have borne witness against him.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024