Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

SCHOOLS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: There is very limited evidence for the way children were educated at home and for the relationship between home and school education. However, it must be noted that home education was probably a pedagogical method as important as schooling. The majority of the working population, including agricultural workers and local craftsmen, probably received their training within a domestic context, rather than at school. The existence of such a household/family-related training context is implied in evidence from Deir el- Medina, suggesting family connections between various groups of craftsmen (cf. the studies on woodcutters and potters). The same may have applied, to a certain extent, even to scribe candidates, since family relations between succeeding scribes are widely attested. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

The study of ancient Egyptian education focuses on the function of the Egyptian schools, which aimed at providing the youth with a basic knowledge in a variety of subjects, such as language and mathematics, as well as at teaching ethics and rules of everyday conduct. The main term employed to denote “education” in the ancient Egyptian language read sbAyt and meant “instruction” with a connotation of “punishment”. This was the same term that featured in the titles of Egyptian works of wisdom known as “Instructions”—a fact that may suggest a pedagogical use of such literary works. Along with sbAyt, the term mtrt was also employed to denote the sense of “instruction,” this time with a connotation of “witnessing” or “personal experience.” The latter term was mainly used in the Late Period, but a semantic difference between mtrt and sbAyt has not been detected.

“In contrast to “education,” whose conventional definition covers aspects of basic training received at school, “apprenticeship” is a term that usually refers to a specific method of instruction, namely the instruction offered by a single teacher to a single or a small number of students on one or more specialized subjects or skills. This was a very popular educational method that was employed mainly when advanced training was sought out in order to develop some of the aspects of the curricula of Egyptian schools, such as writing or mathematics, or to introduce new subjects and skills, such as the study of religious texts or the learning of a craft. In addition, apprenticeship was a manner of instruction that was probably also used in some local Egyptian schools even for basic training— perhaps due to the small number of teachers and students available.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN EDUCATION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Jon Manchip White (2012) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

“The Teachings of Ptahhotep: The Oldest Book in the World” by Ptahhotep (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Wisdom Texts” by Muata Ashby (2006) Amazon.com;

“Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt”

by Raffaella Cribiore (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Loyalist Teaching": an important teaching text: “Loyalist Teaching Sehetepibra: Hieroglyph text and English translation by Frederick Lauritzen (2020) . Amazon.com;

“Instructions of Amenemhat" is another important teaching text;

“Ancient Egyptian Scribes: A Cultural Exploration” by Niv Allon and Hana Navratilova | (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Language and Writing: The History and Legacy of Hieroglyphs and Scripts in Ancient Egypt” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Scribes

Much of Ancient Egyptian schooling was oriented towards scribes. Being a scribe in ancient Egypt was a high-status position in ancient Egypt, especially since only 1 percent to 5 percent of the ancient Egyptian population could read and write, according to the University College London. The ancient Egyptians believed that writing was invented by the ibis headed god Thoth and that words had magical powers.

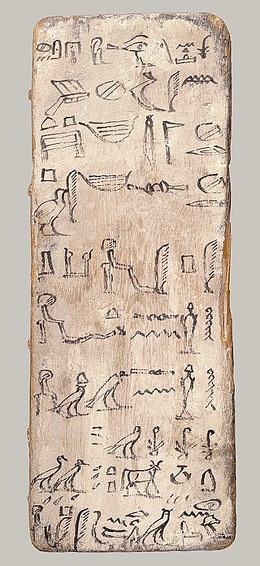

Scribes belonged to a caste. When students were being taught by the fathers they practiced their hieroglyphics on stones and potsherds before they wrote on papyrus. Describing the importance of the profession one ancient Egyptian poet wrote: "It's the greatest of all calling/ Thee is none like it in the land/Set your heart on books!/...There's nothing better than books!" "See, there's no profession without a boss/ Except for the scribe ; he is the boss." [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

One papyrus, translated by Miriam Lichtheim, says, ''Happy is the heart of him who writes; he is young each day ... Be a scribe! Your body will be sleek, your hand will be soft ... You are one who sits grandly in your house; your servants answer speedily; beer is poured copiously; all who see you rejoice in good cheer.''

See Separate Article: SCRIBES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Access to Schools in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “It is this connection to specific individuals that has led to the Egyptological consensus that not all individuals had access to a school education. Instead, it seems that school education was primarily for the elite and mostly for the male members of the Egyptian society, who were destined to work for the main Egyptian socio-political and religious institutions, such as the palace, the treasury, or the temple. It should be noted here that, although many priests also bore the title of the scribe, no school texts make direct references to the priestly profession as a goal of education. Perhaps this suggests that the priestly duties were taught after school, as part of an advanced apprenticeship in a temple, or that the children who were destined to become priests were trained in separate, special schools. The “be-a-scribe” orientation of Egyptian education is at the heart of most of the discovered Egyptian schoolbooks. Thus, for instance, in the Ramesside miscellany of Papyrus Lansing one encounters a number of short texts praising the scribal profession: ‘Befriend the scroll, the palette. It pleases more than wine. Writing for him who knows it is better than all other professions. It pleases more than bread and beer, more than clothing and ointment. It is worth more than an inheritance in Egypt, than a tomb in the West.’ [Papyrus BM 9994, 2,2 - 2,4] [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The apparent limited accessibility to schooling in ancient Egypt has also been one of the reasons some scholars have argued that literacy in most phases of Egyptian history was restricted to a very low percentage of the population, in some cases amounting only to 1 percent. Estimating degrees of literacy in ancient Egypt is, however, a very difficult task. Also, although nowadays literacy equals education, in ancient Egypt most men and women would have been illiterate, due to the limited orientation and accessibility of school education; but that does not necessarily mean that they were uneducated too, since home education and craftsman apprenticeship would train them in areas of specialized knowledge that did not require knowledge of writing or reading. Such home education was also likely for women, for whom there is no solid evidence that they could ever enter schools and be trained to read and write.

“At the same time, there may be some exceptions to the rule of education accessibility according to social status. Hence, for example, in the Middle Kingdom Instruction of Dua-Khety, or the Satire of the Trades as it is often also called, Dua-Khety, who apparently did not hold any important positions in his hometown, escorts his son to the 12th Dynasty Egyptian capital (probably near el-Lisht) where his son is to be admitted to the scribal school together with the children of the elite. Given that there is no reference to a special permission or reward granted to Dua-Khety, this situation seems to reflect an open admission to such schools, including children of lower classes, although it should probably be best taken simply as a piece of literary fiction.”

Types of Schools in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “The term probably used by the Egyptians to refer to a school, as an educational institute rather than a certain space in which teaching was taking place, read pr-anx, “house of life”. In addition, there is the less commonly employed term at-sbA, “house of instruction,” which could denote the school as a space. The meaning of pr-anx is still debated, since scholarly circles are divided between its translation as “school” and as “scriptorium” (that is, the space in which scribes worked— studying, producing, and copying various texts) or “university” (in the sense of an institute of advanced learning in contrast to the basic teaching offered in a common school). [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

The pr-anx in the sense of a scriptorium is closely associated with the function of the Egyptian temple, given that most of the major temples included libraries and archives that were probably managed and maintained by scribes, the primary product of school education (for the existence of temple libraries and archives). However, there is very little evidence for the exact locations of the pr-anx or any other space used for teaching. Such evidence points towards the existence of schools, for instance, around the Ramesseum, at Deir el-Medina, and at the Mut temple in Karnak. No exact locations can be identified, however, mainly because schooling in Egypt probably took place outdoors and its location was not always fixed. References to the existence of a pr-anx vary from titles revealing a connection between administrative positions and school activity to actual references to a pr-anx in association with the life and activities of certain individuals.

Scribe School in Ancient Egypt

The boy who was intended for the profession of scribe was sent when quite young into the instruction house, the school, where, even if he was of low rank, he was “brought up with the children of princes and called to this profession. "' In old times the school for scribes was attached to the court; ' the schools of the New Kingdom must have been organised differently, for it seems that the various government departments, such as the house of silver, etc., had their own schools, in which the candidates for the respective official positions were educated. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

From various passages in the school literature we know that the individual training of the young scribes was carried on by one of the higher officials of the department to whom they were assigned as pupils and subordinates. One of these pupils writes to his tutor: “I was with thcc since I was brought up as a child; thou didst beat my back and thy instructions went into m\ car. " '' From this we may assume that there was no disconnection at all between the early teaching and the later higher instruction; it seems that the same old official who initiated his disciple “into his duties, had also to superintend his work when he had to learn the first elements of knowledge.

It was quite possible for a boy to enter a different profession from that for which he was educated at school; Bekenchons the high priest of Amun relates that, from his fifth to his sixteenth year, he had been ''captain in the royal stable for education," and had then entered the temple of Amun in the lowest rank of priesthood. After serving as a cadet, as we should say, he entered the ecclesiastical profession. The stable for education must have been a sort of military school, in which boys of rank who were intended to be officers in the army became as a rule “captains of the stable. " '"

School Curriculum in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “Egyptian pupils entered school probably at the age of four or five and there they were mainly taught how to read and write (including the rules of rhetoric and proper speech), geography, mathematics, and geometry. In addition, there is some evidence for the learning of foreign languages in New Kingdom schools, a fact that historically corresponds to the era of Egyptian imperialism and of the extension of Egyptian foreign relations. This evidence, however, which includes, for example, lists of foreign words or names, is far from conclusive, since it shows more an acquaintance with foreign vocabulary, possibly used in Egyptian texts, rather than mastery over a foreign language. Nevertheless, the occasional use of foreign languages in Egyptian administration was surely a result of some training in foreign languages that could have taken place either in the Egyptian capital or in foreign schools. In addition to these subjects, sports, music, and other arts could have also featured in Egyptian education. The evidence for the treatment of such subjects is, however, scarce. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The first script an Egyptian pupil learnt how to read and write was probably hieratic, which was later (ca. fourth century B.C. onwards) replaced by Demotic. These were the scripts the pupils used to practice writing letters and various types of administrative documents. They were also exposed to literary works, whose language and style often differ from those used in documentary texts. That was the case, for example, in the New Kingdom, when older literary works in Middle Egyptian were studied in school along with works written in Late Egyptian.

The pupil was taught language by doing a lot of spelling and grammar exercises, writing passages dictated by the teacher, and copying parts of real or model documentary and literary texts. Such model texts are found in the so-called “miscellanies”, which could be compilations made by teachers for classroom use. Given that some of the texts copied in schools were instructive, teaching mainly about general ethics, the Egyptian pupil was educated also through the study of the contents of such didactic texts. Probably at a later stage, the pupils learnt how to read and write hieroglyphs, the main script for monumental and archaizing writing during most periods of Egyptian history.

An oft- quoted case of a graffiti from Northern Saqqara, written by a school teacher, appears to show that he visited tombs in that area together with his pupils as part of a school excursion. During this outing they may have studied funerary stelae as records of a recent or distant historical past. Such assumptions, however, implying that history was included in the curriculum of Egyptian schools, are only based upon scarce evidence and cannot be conclusive.

Teaching Methods in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “An exemplary educational career of an elite child, who was to become high priest of Amun at Karnak, is described in the biographical texts inscribed on two block statues of Bakenkhons, now in Cairo and Munich. In these texts Bakenkhons mentions among other things: ‘I spent 4 years as an excellent youngster. I spent 11 years as a youth, as a trainee stable-master.’ [Munich statue, Gl. WAF 38, back pillar] ‘I came out from the room of writing in the temple of the lady of the sky as an excellent youngster. I was taught to be a wab-priest in the domain of Amun.’ [Cairo statue, Cairo CG 42155, back pillar (translated in Frood 2007: 43)] [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In contrast to the considerable amount of evidence available for basic school education in ancient Egypt, there is much less evidence for apprenticeship in advanced or special subjects and skills. Such evidence includes, for example, painted ostraca from Deir el-Medina that could have been made by artisan apprentices in situ. Probable references to such young apprentices are made in other ostraca from Deir el-Medina. Finally, there is also some evidence of the manner in which temple musicians were trained.

Overall, the method of knowledge transfer through apprenticeship in Pharaonic Egypt was most likely informal and circumstantial, based not so much upon a uniform curriculum but rather upon the personal choices of the experienced professional who took over the education of his potential successors. The close relationship between artisan apprenticeship and school education is evident in the case of a number of tombs, in the context of which school exercises have been discovered. This evidence might indicate that Egyptian students were learning how to read and write by using the material inscribed on tomb walls. After all, tombs in ancient Egypt probably also functioned as places where important works of literature were meant to be preserved. In such cases, the artisan master who was overseeing the works in tombs would probably have also acted more broadly as a teacher.”

Instruction in Ancient Egypt

Fortunately our sources of information enable us to follow the broad outlines of the form and kind of instruction which was given in this ancient period. The school discipline was severe. The boy was not allowed to oversleep himself: "The books are (already) in the hands of thy companions, take hold of thy clothes, and call for thy sandals," says the scribe crossly as he awakes the scholar. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Lesson time, the results of which were said to “endure for ever like the mountains," ' took up half the day, when “noon was announced “the children left the school sJiouting for joy. The food of the school children must have been rather sparing — three rolls of bread and two jugs of beer had to suffice for a schoolboy;"" this was brought to him daily by his mother from home. On the other hand there was plenty of flogging, and the foundation of all the teaching was: “The youth has a back, he attends when it is beaten. " ' A former schoolboy writes thus to his old tutor, from whom he has received yet severer punishments: “Thou hast made me buckle to since the time that I was one of thy pupils. I spent my time in the lock-up; he bound my limbs. He sentenced me to three months, and I was bound in the temple. " '

scribe palette and tablet

The Egyptians justified this severity in theory. The usual argument was that man was able to tame all animals; the Ka'ere, which was brought from Ethiopia, learnt to understand speech and singing; lions were instructed, horses broken in, hawks were trained, and why should not a young scribe be broken in in the same way? '' As however he was not quite on a par with lions or horses, these pedagogues used admonishment also • as a useful expedient. This was applied unceasingly; whether the schoolboy was "in bed or awake" he was always instructed and admonished.

Sometimes he hears:

“O scribe, be not lazy, otherwise thou wilt have to be made obedient by correction. Do not spend thy time in wishing, or thou wilt come to a bad end.

Let thy mouth read the book in thy hand, take advice from those who know more than thou dost. Prepare thyself for the office of a prince, that thou mayst attain thereto when thou art old. Happy the scribe who is skilled in all his official duties. Be strong and active in thy daily work.

Spend no day in idleness, or thou wilt be flogged. For the ears of the young are placed on the back, and he hears when he is flogged.

Let thy heart attend to what I say; that will bring thee to happiness. . . . Be zealous in asking counsel — do not neglect it in writing; do not get disgusted with it. Let thy heart attend to my words, thus wilt thou find thy happiness. "

Copy Books in Ancient Egypt

A number of letters and passages have come down to us in copy-books. It is evident that the letters are mostly fictitious, partly from their contents, which are usually couched in general terms, and partly from the fact that the same letter is repeated in the various school copy-books under different names. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

An Egyptian copy-book is easily recognised; its size is peculiar as well as its shape; the pages are short, and contain a few long lines, while on the upper edge of these pages there are usually the tutor's corrections, which are generally of a calligraphic nature. It is interesting to find on one of these school papyri the date, the 24th of Epiphi written in on the right-hand side; three pages before we find the 23rd of Epiphi, and three pages after, the 25th Epiphi; evidently three pages was the daily task the pupil had to write. This may not seem much, but we must remember that these pupils had at the same time to do some practical work in the department.

We learn this also from their copy-books, not from that part which was shown to the teacher, but from the reverse sides. The back of the papyrus rolls, which was supposed to be left blank, was often used by the Egyptians as a note-book; and a few hasty words jotted down there by the young scribe are often of more interest to us than the careful 'writing on the other side. There are many of these scribbles on the backs of the copy-books, and the little pictures of lions and oxen, specimens of writing of all kinds, bills of the number of sacks of grain received, or drafts of business letters and the like, show us the sort of practical work the owners of these rolls of books did for the department in which they had been entered. When we observe the astonishing early maturity of the modern Egyptian bo} percent we need not be surprised that these twelve or fourteen-yearold scribes of antiquity had already learnt to be really useful to the authorities.

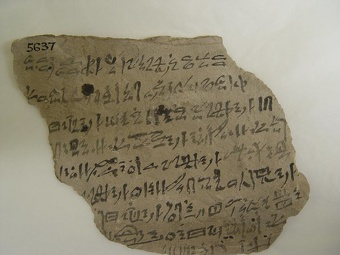

School Ostraca

According to a report by Smithsonian Magazine, researchers excavating the city of Athribis, an ancient settlement in lower Egypt, discovered more than 18,000 pieces of ostraca (inscribed pottery shards), many of them from a school, dating to the Ptolemaic era 305-30 B.C. Madeline Buiano wrote in , Martha Stewart Living: “The inked pottery pieces were an affordable and more accessible alternative to papyrus. The remains of broken jars and other vessels were inscribed by dipping a reed or hollow stick in ink to detail receipts, record trades, lists of names, copy literature, and teach students how to write and draw. [Source: Madeline Buiano, Martha Stewart Living, February 11, 2022]

“More than a hundred of the ostraca are covered in repetitive writing exercises, thought to be a form of punishment for students that misbehaved. "There are lists of months, numbers, arithmetic problems, grammar exercises, and a 'bird alphabet' — each letter was assigned a bird whose name began with that letter," says Christian Leitz in a statement. Leitz is a professor at the University of Tübingen in Germany and led the excavations alongside Egypt's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

“Nearly all (80 percent) of the pottery pieces are written in demotic, an administrative script used during the reign of Cleopatra's father, Ptolemy. Greek is the second-most common script, but hieroglyphics, Arabic and Coptic — a mix of Greek and Egyptian languages — also appear, hinting at the city's robust multicultural history.

An ostracon dated to 1295-1069 B.C. found Near Luxor (ancient Thebes), Egypt and measuring 9 centimeters high and 8 centimeters wide (3.7 inches high, 3.3 inches wide), appears to have been used by ancient Egyptian art students for an exercise. According to Archaeology magazine: “One of the important events along this path to the afterlife was a ritual called the “Opening of the Mouth,” during which the dead, in the form of an inanimate object such as a cult statue or tomb painting, or an actual deceased person — likely a mummy — was symbolically brought back to life by a priest. This small piece of pottery described above seems to be evidence that the ancient Egyptians also loved a good joke, even one at the expense of their most sacred rituals. [Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

“Ostraca, were inexpensive and readily available across the ancient world, and were used as a kind of paper. This ostracon was found by archaeologist Flinders Petrie in the late nineteenth century in an area identified as an artists’ school behind the Ramesseum, a large temple across the Nile from ancient Thebes. More than 3,000 years ago, a student painted this image of a girl, who is depicted in profile, the traditional way of representing a statue. Perhaps this was a practice sketch — although one executed with not inconsiderable skill. According to Egyptologist Stephen Quirke of University College London, by adding a depiction of a monkey, the student may have been attempting to create a caricature of the “Opening of the Mouth” ritual.

Copying Passages as a Means of Instruction in Ancient Egypt

As soon as the scholars had thoroughly mastered the secrets of the art of writing, the instruction consisted chiefly in giving them passages to copy, so that they might at the same time practise their calligraphy and orthography and also form their style. Sometimes the teacher chose a text without much regard to the contents — a fairy-tale," a passage from some religious or magical book, a modern or an ancient poem '' — the latter was especially preferred, when it would impress the youth by its ingenious enigmatical language. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

More frequently, however, he chose his specimen, so that it might tend to the education of his pupil; he gave him a sbayt, that is an instriiction, to copy. These instritctions, which we shall consider more closely in the next chapter, are of two kinds. In the first place most of those of the time of the Middle Kingdom contain rules for wise conduct and good manners, which are put into the mouth of a wise man of old times.

The others, which are of later date, are instructions in the form of letters, a fictitious correspondence between tutor and pupil,' in which the former is supposed to impart wisdom and at the same time a fine epistolary style. It was of course only exceptionally that the teacher would compose these letters himself, he preferred to take them word for word out of books, or sometimes to paraphrase some other person's letter. “This did not however prevent many tutors and pupils from signing their own names to these old letters, as if the}" were really carrying on a correspondence with one another.

School Exercises in Ancient Egypt

scribe's palette

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “In the case of ancient Egypt, we have so far: 1) numerous copies of school exercises surviving mainly on pottery or stone ostraca (a potsherd used as a writing surface), on wooden or stone tablets, or on small papyrus fragments, coming from a great variety of localities, and dating to almost all phases of Egyptian history; 2) a considerable number of copies of schoolbooks, such as the Middle Kingdom standard version of a schoolbook known as Kemit, “the complete one” or “the summary”; and 3) a large number of references to school activity and educational methods in a range of textual sources from biographical inscriptions to the content of schoolbooks themselves, such as, for instance, a reference to the copying of one chapter per day as discussed by Fischer-Elfert. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian school exercises vary from basic exercises of grammar and orthography to copies of actual literary or documentary texts. There is a certain degree of difficulty in distinguishing between “professional” copies of texts produced by scribes and student copies produced in schools. In most of the cases, what determines whether a text is a student product are the material used as writing surface, the context of the artifact, as well as the style of writing and the contents. Hence, for instance, a school exercise, as mentioned above, was most frequently inscribed on pottery or stone ostraca that were useless otherwise. As far as the context is concerned, school exercises tend to be found in clusters, reflecting a massive use by a group of students and teachers. The location, however, of such quantities of easily moveable material is seldom used to locate an Egyptian school, a task that has so far proven to be very difficult (see below). Finally, the most defining characteristics of a school exercise are the contents of the inscribed text, which in most cases was in the form of a list of words or phrases, as well as the style of writing, which was mostly crude, full of mistakes, and corrections.

“In the case of apprenticeship in ancient Egypt, the available evidence concerns mainly the training of draftsmen and consists of: a) practice ostraca, and b) textual references to artisan training. As with school exercises, practice material can be identified as such due to their crude drawings and the fact that they were painted on ostraca.”

Arithmetic and Math Studies in Ancient Egypt

Mathematics served a practical purpose for the ancient Egyptians — they only solved the problems of everyday life, they never formulated and worked out problems for their own sake. How certain eatables were to be divided as payments of wages; how, in the exchange of bread for beer the respective value was to be determined when converted into a quantity of corn; how to reckon the size of a field; how to determine whether a given quantity of grain would go into a granary of a certain size — these and similar problems were taught in the arithmetic book. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In pure arithmetical examples there are no errors as far as I can see, at most a small fraction is sometimes purposely disregarded. Everything is worked out in the slowest and most cumbrous manner — even the multiplication of the most simple numbers. If, for instance, the schoolboy had to find out in his sum the product of 8 times 8, this difficult problem would be written out.

Evidently in mental arithmetic, he was only equal to multiplication by 2; Strange to say also, he had no proper method for division; he scarcely seems to have had a clear idea of what division meant. He did not ask how many times 7 was contained in y, but with which number 7 was to be multiplied that the product might be y. In order to discover the answer he wrote out the multiplication table of 7, in the various small numbers, and then tried which of these products added together would give y.

In this instance the multiplicators belonging to 7 and 14 and 56 are marked by the pupil with a stroke and give the numbers wanted. Therefore it is necessary to multiply 7 by 1+2 + 8, in order to obtain the y. In connection with this imperfect understanding of division, it is easy to understand that the Egyptian student had no fractions in our arithmetical sense. He could quite well comprehend that a thing could be divided into a certain number of parts, and he had a special term for such a part, such as re-met = mouth often, such as a tenth. This part however was always a unit to him, he never thought of it in the plural; they could speak of “one tenth and a tenth and a tenth “or “of a fifth and a tenth,"

Two thirds was an exception; for he possessed a term and a sign for it. He could not deal with fractions other than the most simple kind. When he had to divide a smaller number by a greater, for instance 5 by 7, he could not represent the result as we do by the fraction, but had to do it in the most tiresome roundabout fashion. He analysed the problem either by the division of 1 by 7 five times, or more usually he took the division of 2 by 7 twice and that of 1 by 7 once. There were special tables which gave him the practical result of the division of 2 by the odd numbers of the first hundred. He thus obtained a number which he then knew how to reduce,

If by this awkward mechanism they obtained sufficiently exact results, it was owing exclusively to the routine of their work. The range of the examples which occurred was such a narrow one, that for each there was an established formula. Each calculation had its special name and its short conventional form, which when once practised was easily repeated.

'Naughty' Students in Egypt Forced to Write Lines 2,000 Year Ago

Among the 18,000 ostraca discovered at Athribis are some that appear to show 'naughty' students forced to write lines as punishment. According to the University of Tübingen Professor Christian Leitz, who led the excavation, "There are lists of months, numbers, arithmetic problems, grammar exercises and a 'bird alphabet' — each letter was assigned a bird whose name began with that letter," Professor Christian Leitz says. [Source: Alia Shoaib, Business Insider, February 12, 2022]

A large number of ostraca also contain writing exercises that the team classifies as punishment. The shards are inscribed with the same one or two characters each time, both on the front and back. Along with written texts, some of the fragments had pictorial representations of animals, gods, and geometric figures.

There are pictorial ostracon with a baboon and an ibis, the two sacred animals of Thoth, the god of wisdom. According to Business Insider: The pottery fragments were inscribed with ink and a reed or hollow stick. Around 80 percent of the shards were inscribed in Demotic, the common administrative script in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, researchers said. The following most common script was Greek, but the team also came across inscriptions in Hieratic, hieroglyphic and more rarely Coptic and Arabic script.

“Researchers said it was "very rare" to find such a large quantity of ostraca, as a discovery of this size had only been made once before, near the Valley of the Kings in Luxor. The ostraca are being analyzed by an international team led by Sandra Lippert, head of research at the Center National de la Recherche Scientifique, and Carolina Teotino from the University of Tübingen is examining the pictorial ostraca.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024