Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

POLICE AND LAW ENFORCEMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Mentuhotep, chief of police in Thebes

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: During the Old and Middle Kingdoms order was kept by local officials with their own private police forces. During the New Kingdom a more centralized police force developed, made up primarily of Egypt’s Nubian allies, the Medjay. They were armed with staffs and used dogs. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Neither rich nor poor citizens were above the law and punishments ranged from confiscation of property, beating and mutilation (including the cutting off of ears and noses) to death without a proper burial. The Egyptians believed that a proper burial was essential for entering the afterlife, so the threat of this last punishment was a real deterrent.”

During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (2613-2181 B.C.) there was no official police force. Leader at that time had personal guards to protect them and hired others to watch over their tombs and monuments. Nobles followed this paradigm and hired trustworthy Egyptians from respectable backgrounds to guard their valuables or themselves. [Source New World Encyclopedia]

In the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570-1069 B.C.) what could described as a police force became more organized and the judicial system as a whole was reformed and developed further. Officials served as police officers prosecutors, interrogators, bailiffs, and also administered punishments. These officials were responsible for enforcing both state and local laws, but there were special units, trained as priests, whose job was to enforce temple law and protocol. These laws often had to do with not only protecting temples and tombs but with preventing blasphemy in the form of inappropriate behavior at festivals or improper observation of religious rites during services.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN JUSTICE SYSTEM factsanddetails.com ;

COURTS OF LAW IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LEGAL PROCEDURES IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN COURTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CRIME IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Law in Ancient Egypt” by Russ VerSteeg (2002) Amazon.com;

“Maat Revealed, Philosophy of Justice in Ancient Egypt” by Anna Mancini (2007) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 1: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

“Judgement of the Pharaoh: Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley

Amazon.com;

“State in Ancient Egypt, The: Power, Challenges and Dynamics” by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian State: The Origins of Egyptian Culture (c. 8000–2000 BC)” by Robert J. Wenke (2009) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

“Ancient Egyptian Administration (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 1; The Near and Middle East) by Juan Carlos Moreno García (2013) Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

Murder and Violent Crimes in Ancient Egypt

Investigation of the Ramesside Tomb Robberies

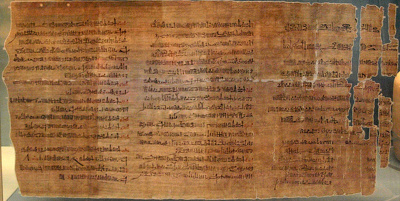

The Ramesside Tomb Robberies refers to the alleged looting of the tombs of nobles in the Valley of the Kings around 1,100 B.C. The documents of the lawsuit connected with the Ramesside Tomb Robberies date the reign of Ramses IX, (about 1,100 B.C.). The accused are a bands of thieves and the document itself gives us a distinct picture of the work of the government police under the 20th dynasty, and how crime was tracked, and how trials of suspected persons were conducted. Under the the Governor of Thebes were princes, who carried on the duties of the old Theban nomarch. The eastern part, the city proper, was under the “prince of the town," the western part, the city of the dead, under the “prince of the west," or the “chief of the police of the necropolis. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

At the time of lawsuit the higher office was held by a certain Paser, the lower by Pawero, and as is not unusual even now with colleagues at the head of two adjacent departments, they lived in open enmity with each other. Their enmity was no secret; and if a discontented subordinate of Pawero thought he observed anything wrong in the city of the dead, he went to Paser and related the tittle-tattle to him, as a contribution to the materials which he was collecting against his colleague. When therefore in the 16th year important thefts were perpetrated in the necropolis, it was not only Pawero, the ruler of the city of the dead, who, as in duty bound, gave information to the governor, but Paser also, the prince of the town, did not let slip this opportunity of denouncing his colleague to the chiefs in council. It is characteristic of the sort of evidence presented by Paser that precisely that royal tomb which he declared to have been robbed was found at the trial to be uninjured: evidently his accusation rested on mere hearsay.

The court of justice, before which both princes had to give their evidence, consisted of a superintendent of the town and governor," assisted by two other high officials, the scribe and the speaker of Pharaoh, or according to their full titles: “the royal vassal Nesamun, scribe of Pharaoh and chief of the property of the high-priestess of Amun-Ra, king of the gods“ and a "royal vassal, the speaker of Pharaoh." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In the Ramesside Tomb Robberies case public confession was not enough; the thieves were also obliged to identify the scene of their crime — there seems to have been a law to this effect. The governor and the royal vassal Nesamun commanded the criminals to be taken in their presence, to the necropolis where they identified the tomb of Sobekemsaf II as that to which their confession referred. Their guilt being finally established, the great princes had now done all they could in the case, for the sentence of punishment had to be pronounced by the Pharaoh himself, to whom they, together with the princes of the town, at once sent the official report of the examination. Meanwhile the thieves were given over to the high priest of Amun, to be confined in the prison of the temple “with their fellow thieves. "[Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Commission to Investigate the Ramesside Tomb Robberies

When these three great princes — top officials in Thebes — heard of the attempt on the great noble necropolis, they sent out a commission of inquiry to investigate the matter on the spot; for this commission they appointed not only the prince of the necropolis himself and two of his police officers, but also a scribe of the governors, a scribe belonging to the treasury department, two high priests, and other confidential persons, who were assisted in their difficult task by the police. As inspectors these officials went through the desert valleys of the city of the dead carefully examining each tomb which was suspected.[Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The result is related in the following document which enumerates the “tomb and mummy-pits examined on this day by the inspectors. 4) The tomb of the king 'Entef the great. It was found that a boring had been made by the thieves at the place where the stele stands. “It was found uninjured, the thieves had not been able to effect an entrance. 5) The tomb of the King Sobekemsaf II: It was found that the thieves had bored a mine and penetrated into the mummy chamber; they had made their way out of the outer hall of the tomb of Nebamun, the superintendent of food under Thutmose III. It was found that the king's burial-place had been robbed of the monarch; in the place also where the royal consort Nubch'as was buried, the thieves had laid hands on her.

“The governor and the prince-vassals ordered a thorough examination to be made, and it was proved exactly by what means the thieves had laid hands on this king and on his royal consort. " This was, however, the only pyramid that had really been broken into; all the other royal tombs were uninjured, and the scribe was able with pride to draw up this sum total at the bottom of the deed: Tombs of the royal ancestors, examined this day by the inspectors: Found uninjured:. Tombs — 9; Found broken into: Tombs — 1. Total – 10

Matters had gone worse with the tombs of private individuals: of the four tombs of the distinguished “singers of the high-priestess of Amun Ra king of the gods," two had been broken into, and of the other private tombs we read — “It was found that they had all been broken into by the thieves, they had torn the lords { such as the bodies) out of their coffins and out of their bandages, they had thrown them on the ground, they had stolen the household stuff which had been buried with them, together with the gold, silver, and jewels found in their bandages. " These were however only private tombs; it was a great comfort that the royal tombs were uninjured. . The commission sent in their report at once to the great princes. At the same time the prince of the necropolis gave in to the prince-vassals the names of the supposed thieves, who were immediately taken into custody. Under torture they confessed to violating the tomb of King Sobekemsaf II.

Later, fresh suspicions arose which had to be followed up. A man of bad repute, who three years before had been examined by a predecessor of the present governor, had lately confessed at an examination that he had been into the tomb of Ese, the wife of Ramses II. and had stolen something out of it. This was the “metalworker Peikharu, son of Charuy and of Mytshere, of the west side of the town, bondservant of the temple of Ramses III. under Amenhotep, the first prophet of Amun Ra king of the gods.

They therefore caused the metalworker to be blindfolded and carried in their presence to the necropolis. “When they arrived there, they unbandaged his eyes, and the princes said to him: ' Go before us to the grave out of which, as thou dost say, thou hast stolen something. ' The metalworker went to one of the graves of the children of the great King Ramses II., which stood open, and in which no one had ever been buried, and to the house of the workman Amenement, son of Huy of the necropolis, and he said: ' Behold, these are the places in which I have been. ' Then the princes ordered him to be thoroughly examined and tortured in the great valley, and they found nevertheless that he knew of no other place besides these two places which he had pointed out. He swore that they might cut off his nose and his ears, or flay him alive, but that he knew of no other place than this open tomb and this house, which he had shown to them.

Part of the information which had led to the examination of the necropolis had been sent directly by Paser; he had maintained officially that the tomb of Amenhotep I. had been robbed. The contrary was now established, and with the exception of the one tomb of Sobekemsaf II,, all the royal tombs were found to be in good order.

See Ramesside Tomb Robberies Under CRIME IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Punishments and Torture in Ancient Egypt

torture by caning the soles of the feat

According to a University of Oxford course outline: For criminal cases, government officials were sent to investigate; these reported to the vizier’s permanent court and the king, and had the power to arrest, detain and question suspects, including through torture. Crimes against the state had harsh penalties, including beatings, the twisting of limbs, mutilation, burning and impalement. Prisons existed but only as places of detention while punishment was decided.

Irene Cordón wrote in National Geographic: When people were convicted of crimes, the penalties depended both on the severity of the offense and their level of involvement. The typical penalty for stealing was returning the stolen object and paying its rightful owner double or triple its value. If someone stole from a temple, however, the punishment was more severe: it could include paying a hundred times the value of the object, corporal punishment, or even death. [Source: Irene Cordón, National Geographic, January 30, 2019]

Little evidence has been found for imprisonment in ancient Egypt. Criminal punishment tended to be administered immediately rather than by means of a long sentence. Forced labor was common, and criminals were also threatened with exile to Nubia, where scholars believe they were put to work in mines. Corporal punishment was also common in the form of public beatings, brandings, or mutilations.

A common torture technique in ancient Egypt was beating the soles of the feet with a stick. The method is still widely used today. Egyptians also used to smear disobedient slaves with ass’s milk and seclude them until they had been thoroughly bitten by ants, fleas and other insects.

Punishments sometimes carried into the Afterlife. According to one record, Teti, founder of the 6th dynasty around 2300 B.C. was assassinated. His successor lasted only two years before Tet's son Pepy I came to power. Pepy punished the assassins and made sure their names and likenesses were chiseled off of tomb engravings after they were dead. [Source: National Geographic, Geographica, July 2000]

Beatings and Mutilations — Sanctioned Violence in Ancient Egypt

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “The dichotomy between acceptable and unacceptable violence was also manifest among humankind. Clearly there were many situations in which violence was viewed as appropriate, even desirable. Sanctioned corporal punishment was prevalent. Old Kingdom tomb scenes frequently show people being beaten, sometimes with sticks that are shaped to look like a man’s hand, often while tied to a post. According to tomb captions and the Satire of Trades , one of the more frequent reasons for beatings was a failure to pay taxes . The Instructions of Amenemope seems to indicate that being among the chronically dependent poor could lead to violent punishment, even possibly execution. Beatings and inflicting open wounds were among the most common forms of punishment and could be inflicted for crimes such as failure to pay a debt, theft, improper appropriation of state workers, bringing charges against a superior , spreading rumors, not prosecuting crimes , unauthorized contact with sacred elements, interference with fishing and fowling , false legal action, libel, or inappropriate entrance of a tomb. The most common beatings consisted of either 100 or 200 blows, and in more se vere punishments were commonly accompanied by five open wounds.[Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Schoolboys could also be beaten for faulty scribal work. This leads to the assumption that beatings would have been viewed as an appropriate disincentive for unworthy behavior or performance in other forms of training. While not extreme, such a practice must have created a somewhat regular feature of mild violence throughout a person’s youth.

“Undoubtedly there were cases in which the violence did not remain mild. Beatings were also used during interrogations. Such a beating, if it produced a confession, could be followed by more beatings or worse punishments. For instance, one man was beaten to get his confession and then beaten with 200 blows of palm rod as punishment. It is possible that the threat of drowning, or perhaps the use of water in torture, were also part of interrogations. Divorce was punishable by beating in one case, though this seems to be an anomaly.

“Mutilation was another common form of violent punishment, most frequently manifested in cutting off the nose or ears. This could happen for various crimes, including encroachment on founda tion fields (agricultural property dedicated to supporting cultic or royal undertakings), interfering with offerings, select thefts, and even for involvement in the harem conspiracy recorded in the reign of Ramesses III. In the latter case, the mutilation of one man was shortly followed by his suicide, perhaps because the mutilation was either too painful or too humiliating to bear.”

Executions in Ancient Egypt

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “While beatings, open wounds, and mutilation were difficult and severe punishments, execution was the most extreme violence of the penalization repertoire. The reasons for and types of execution varied over time, but sanctioned violent death remained an invariable part of Egyptian society . [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Pharaoh smiting an enemy at Bet el-Wali

“Death by burning was a consistent type of violence employed throughout Egyptian history, though the evidence for it increased sharply after the end of the Ramesside Period. Decapitation was one of the more frequent to ols of death early in Egyptian history, but appears to have declined from the Ramesside era on. Slaying in a ritual context (i.e., sanctioned killing that involved demonstrable ritual trappings) was consistently employed over time. Drowni ng was also sometimes employed. Impalement was infrequently used, except during the Ramesside era, when it seems to have been the preferred form of punishment.

“While in many cases we know that either the king or vizier approved of executions, we do not have enough evidence to know if this was always the case. We are also unable to determine why some methods of killing were preferred vis-à-vis others in various time periods. “Similar to the methods of execution, the reasons for execution also demonstrate both consistency and change over time. While it is difficult to detect a consistent pattern, one small repetitive theme is that the disruption of cult could often result in ritualized execution. Other than this, our sources are generally silent as to why capital punishment was deemed necessary, a notable exception being in the harem conspiracy, wherein those being executed understood that it was because they had committed “the abomination of every god and every goddess”. Yet the general (and surely simplified) pattern indicates that capital punishment was usually a result of crimes, which were deemed to be against the state or the gods .

“These types of crimes were viewed as disruptive of order, inviting chaos. These acts were typically (though not uniformly) painted as some sort of rebellion, such as the many tomb inscriptions that labeled anyone who violated the tomb as a rebel. On the part of the state, violence was employed in the service of order. It was designed to rectify unacceptable situations or, in other words, to return to the order of the original creative state.Execution for the rebellious was a constant.”

Crimes Worthy of Execution in Ancient Egypt

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “It appears that death for stealing or damaging state property was also fairly uniform, though it is difficult to assess this with confidence since we only have evidence from a few time periods, such as the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period. Similarly, one would assume that execution for murder would have been invariable, but we only have evidence for murder from the Third Intermediate Period forward. Desecration of sacred land could be grounds for execution. Runaway (royal?) slaves could be deemed worthy of death. [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Ramses II slaying his enemies

“Desecration of royal tombs was viewed as a capital offense. Also, death was sometimes the punishment decreed for interference with mortuary cults, rendering false rulings, rendering false oracles, non-royal tomb desecration, interfering with temple cults, embezzling cultic proceeds, diverting corvée labor, issuing false documents, or stealing state property . In some decrees these acts are deemed worthy of death, and in others they are given lighter, though still violent and harsh, punishments. Even within the same decree the punishments vary without appar ent rhyme or reason. For example, in Seti I’s Nauri decree, he stipulates various beatings, wounding, and restitutions for embezzling and reselling temple estate goods. Yet if these crimes were committed by a k eeper of hounds or keeper of cattle, they were to be impaled. The inconsistency of punishments in the decree is hard to explain.

“The most famous cases of sanctioned violence stem from the texts recording the trial of harem conspirators under Ramesses III and those recording the trials of those involved in tomb robbery in the late 20th Dynasty. In both cases those directly responsible for the crimes met death. In the harem conspiracy, almost all those who were merely aware of the consp iracy were put to death or were allowed to commit suicide. Despite the arguments of many scholars, there is no apparent pattern to explain why some individuals were put to d eath while others were permitted to commit suicide.

“Numerous texts indicate that capital punishment for unspecified criminal activity was an ongoing practice that continued throughout Egyptian history. Attestations of this are fou nd in graffiti, which speak of desecrators’ “flesh...burning together with the criminals,” or being cooked with the criminals. A Coffin Text descendant of the spell from the Pyramid Texts often termed the “Cannibal Hymn” also mentions burning criminals. The transformation of the Cannibal Hymn into this Coffin Text suggests it is based, to some degree, on a continuing reality, for the text seems to have pres erved the idea of its original Pyramid Text form, yet contains within it elements, which appear to have incorporated dynamic changes to the event it describes. The dynamic elements indicate that at the time the Coffin Text was created, some evolved form of a practice continued. We cannot determine if the crimes referred to in this type of reference are those noted above or if they refer to a specific type of crime in addition to those listed above that was deemed worthy of death. Some have argued that killing was sanctioned in the case of a cuckolded husband in regards to the man with whom his wife had slept. The arguments for this are speculative and the evidence is inconclusive.”

See Separate Article: RAMSES III (1195 – 1164 B.C.): HIS RULE, FAMILY, WARS AND THE HAREM CONSPIRACY africame.factsanddetails.com

Justification of Violence in Ancient Egypt

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “In most of the iconography and texts that depict violence, it is the king who is the perpetrator. Most violence we know of is royal violence. However, even royal violence was viewed with ambivalence. Kings both decried violence among others and extolled their own violent exercises. They claimed to have avoided violence, yet publicly portrayed it. For example, Sinuhe describes Senusret I as “a lord of kindness, great of sweetness. He conquered through love.” Yet lines later Senusret is reported to be a “vengeful smasher of foreheads, one who subjugates countries, slaying with only one blow, and one who will strike Asiatics and trample sand dwellers”. Were this a singular reference, it might be ascribed to the literary nature of the work, but it is just one example of a long tradition of juxtaposing the violence and non-violence of the king, such as in the Loyalist Instruction. Thus, in one decree, th e late 18th Dynasty king Horemheb claims to repel violence (or aggressive oppression, Adw ) and decrees death for those who are false in office. [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“In the Cannibal Hymn from the Pyramid Texts, the king is depicted being violent towards even the gods, an accolade of violence however symbolic the reference may or may not be. Formulaic texts expressed the proclaimed ideal of the king and culture, yet could also be contradicted by other formulas expressing contrary ideals. For example, many of the same kings who employed some form of the negative confession in their funerary accoutrements, wherein they claim not to have slain men nor to have ordered them to be slain, nor even to have been violent, also slew men or ordered them to be slain, and repeatedly bragged of being violent, such as when Ramesses III describes himself at Medinet Habu as “a violent ruler, Lord of the Two Lands”. This phrase is used to describe pharaohs from the time of Senusret I through the Ptolemaic era. Kings regularly and formulaically proclaimed their violent acts and abilities.

“Thus we are presented with an understandable paradox. Clearly, there was a proper time for the king and his kingdom to be violent. Yet at other times he and his subjects were supposed to eschew violence. Violence is often portrayed negatively. Weni proudly proclaims that he did not allow anyone to attack another. At Deir el-Medina, some foremen were punished for being too violent, indicating that perhaps a certain level of violence was acceptable but not to be exceeded. The classical author Diodorus Siculus reports that an individual could be punished for not helping someone who was being attacked.

Egyptains attacking Nubians

“Priests were instructed not to hit because it could bring about too much ha rm. Tomb inscriptions boast of their protagonist’s restraint: “never did I beat a man so that he fell, I didn’t sleep in anger”. But some inscriptions simultaneously decry and espouse violence, such as an Old Kingdom official who claims both to have pacified the angry so that violence was avoided and to have sent some to the great house to be beaten. The First Intermediate Period nomarch/warlord Ankhtifi proudly proclaims he did not allow the heat of strife, and yet decrees violence for those who do not follow his wishes. These and a multitude of other sources make it clear that there were situat ions in which violence was to be used, and others in which it should be avoided. Violence was even an appropriate means for stamping out violence.

“The Egyptians themselves dealt with this apparent (and natural) contradiction by juxtaposing the two ideas, e specially in regards to royalty. For example, a non-royal inscription describes Senusret III as “Bastet protecting the Two Lands. He who adores him will escape his arm. He is Sakhmet toward him who transgresses his command. He is calm to those who are satisfied”. The appropriateness of the king’s violence mirrors that of the gods. According to the Pyramid Texts, before mankind rebelled was the time “before there was strife”. After the rebellion the creator slew his own children. Likewise, pharaoh, the gods’ representative on earth, had to employ violence as part of the attempt to bring the world back to the order it had enjoyed before violence had erupted. Of Amenemhet I it was said, “his majesty came to drive out isfet , appearing as Atum himself, setting in order that which he found decaying.

“. . . since he loves maat so much”. Tutankhamen “drove out isfet so that he could reestablish maat , as it had been in sep tepi [or the first moment of creation]”. A royal ritual text states that the purpose of having a king on earth was “so that he may bring about maat , so that he may destroy isfet ”. As the king paralleled his divine counterparts in his use of violence against Chaos, he was assisted by a number of supernatural elements, such as the divine crowns, the uraeus, the eyes of Ra or Horus, and various gods. In these efforts the king was often compared to the gods, such as when Ramesses II says “I was like Ra when he rises at dawn. My rays burned the flesh of the rebels”.

“In general, the ideal was that violence was to be avoided. Yet when isfet needed to be destroyed, violence was the appropriate response. While a study examining the changes in all forms of violence over time remains to be done, we do know something of these changes for sanctioned killing. When allowing for changes in the availability of evidence, we see that sanctioned ki lling remained fairly consistent throughout Egyptian culture. As for the manner of inflicting it, decapitation appeared to drop in use over time while burning rose. Impalement arose largely from the New Kingdom on. Ritual slaying appears to have remained constant. Evidence supporting reasons for sanctioned killing suggests that executing rebels was consistent, but it also indicates that slaying because of damaging or stealing state property, or for murder, was a later phenomenon, though this may be due to a change in the kinds of sources available and the types of events it was thought appropriate to record. Non-sanctioned Violence Despite the ideology of avoiding violence outside sanctioned domains, undoubtedly Egypt had its share of violent citizens. However, very few genres or occasions would have called for the recording of violent acts. When we do learn of non-sanctioned violence, it seems to be largely due to the accident of preservation. Letters and ostraca are one source for learning of such violence. From these we know that some in Deir el-Medina beat their inferiors, and even that one man was beaten for reporting that a superior had slept with his wife.”

Amenhotep I Meets Out Justice After His Death

Amenhotep I (1525–1504 B.C.) became a god after his death and was the focus of an important cult in Thebes. His followers consulted him on questions of justice. Irene Cordón wrote in National Geographic: The second king of the 18th dynasty, Amenhotep I consolidated Egyptian power following his father’s expulsion of the Hyksos invaders from Lower Egypt. Although his own tomb has not been found, Amenhotep I is believed to have started the tradition of rulers being buried in the Valley of the Kings. He and his mother, Ahmose Nefertari, are also credited with founding the village at Deir el Medina and were worshipped as patron gods there.[Source: Irene Cordón, National Geographic, January 30, 2019]

Although it was common for especially renowned pharaohs to become the center of cults after their death, Amenhotep’s is among the most popular and enduring. Egyptians believed that his spirit resided in his oracular statue and proper ceremonies could summon it. Residents often turned to the statue to settle legal disputes.

Bearing Amenhotep I’s statue on their shoulders, priests would carry it out of the temple during processions and on feast days. A crowd would gather around it, and litigants would present their cases to the statue. Each side would present its case or question, either verbally or in writing. The god’s answers were interpreted by its swaying movements.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024