Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Based on the displays of wealth at 3700-year-old site in Abydos, where a large palace was found, and a 2600-year-old site at the Bahariya Oasis, where a rich tomb was found, archaeologists have deduced that sometimes governors and mayors amassed great political power and in some cases may have challenged the ruling pharaohs.

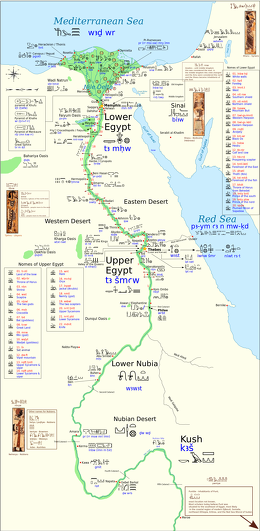

For all intents and purposes ancient Egypt was created when Upper and Lower Egypt were united around 3100 B.C.. Upper Egypt refers to southern Egypt, specifically to the Nile Valley south of Cairo. Lower Egypt refers to northern Egypt, usually the Nile Delta, north of Cairo. The regions are so named because Upper Egypt is along the upriver section of the Nile and Lower Egypt is located on the down river section of the Nile. The Nile flows from south to north.

Throughout ancient Egyptian history the twofold division was always maintained; the whole government was split up into “two houses," and the temple property, or the public lands, belonged to the “two houses, the southern and the northern." In theory all state property was divided into two parts, and the high officials, whose province it was to supervise the treasury or the granaries, were always called the superintendents of the “two houses of silver," or of the “two storehouses."

In spite of some changes and innovations, the Middle Kingdom rested on the same political basis as the Old Kingdom; on the other hand, during the New Kingdom, the constitution of the state must be regarded as a new creation. Many of the old courts of jurisdiction and many titles still existed in this later period, but the fundamental principles of the government were so much changed that these resemblances could only be external. In the first place, during the New Kingdom the provincial governments on which the old state rested have entirely disappeared; there are no longer any nomarchs; the old aristocracy has made way for royal officials, and the landed property has passed out of the hands of the old families into the possession of the crown and of the great temples. This is doubtless the effect of the rule of the Hyksos and of their wars. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Positions included “deputy governor of the treasurers; “' the “clerk to this governor," ' the “clerk of the house of silver," the “chief clerk of the treasury," the “custodian of the house of silver," the “superintendent of the officials of the house of silver". Even these lower officials became personages of distinction and importance. Like the members of the old aristocracy, they kept servants and slaves,' and erected for themselves splendid tombs at Abydos. Some say they formed a middle class of ancient Egypt.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Local Government in Egypt: Structure, Process, and the Challenges of Reform

by James B. Mayfield (1996) Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Administration (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 1; The Near and Middle East) by Juan Carlos Moreno García (2013) Amazon.com;

“State in Ancient Egypt, The: Power, Challenges and Dynamics” by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia (2019) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 1: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

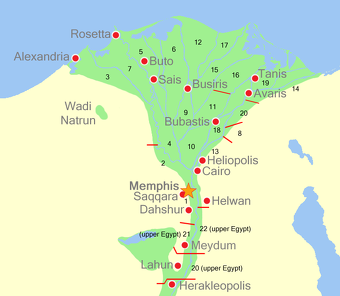

Nomes (Provinces) of Ancient Egypt

Nomes of Lower Egypt: Nome 1: White Walls Nome; Nome 2: Travellers land; Nome 3: Cattle land; Nome 4: Southern shield land; Nome 5: Northern shield land; Nome 6: Mountain bull land; Nome 7: West harpoon land; Nome 8: East harpoon land; Nome 9: Andjety god land; Nome 10: Black bull land; Nome 11: Heseb bull land; Nome 12: Calf and Cow land; Nome 13: Prospering Sceptre land; Nome 14: Eastmost land; Nome 15: Ibis-Tehut land; Nome 16: Fish land; Nome 17: The throne land; Nome 18: Prince of the South land; Nome 19: Prince of the North land; Nome 20: Sopdu-Plumed Falcon land

Though differing in number over time, traditionally there were 42 nomes (provinces) in ancient Egypt —22 in Upper Egypt and 20 in Lower Egypt. Monuments of the earlier periods show us that this was in fact an old national division: many of the names of these provinces occurring in the inscriptions of the Old Kingdom. The basis alone of this division remained unchanged; in certain particulars there were many alterations and fluctuations, such as in the number and in the boundaries of the provinces, especially in the Delta, which appears later to have been entirely divided into twenty provinces, in imitation of the twenty provinces of Upper Egypt. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The official list of these provinces varied at different times, sometimes the same tract of land is represented as an independent province, and sometimes as a subdivision of that next to it. The provinces were government districts, and these might change either with a change of government or for political reasons, but the basis of this division of the country was always the same, and was part of the flesh and blood of the nation.

The names of the nomes varied. Some appear to have naturally occurred. In Upper Egypt we find: the province of the “hare," of the “gazelle," two of the “sycamore," two of the “palm," one of the “knife," whilst the most southern portion was called simply the "land in front. " In the Delta the home of cattle-breeding we find the province of the ''black ox," of the "calf," etc. Other names were derived from the religion; thus the second nome of Upper Egypt was called "the scat of lions," the sixth "his mountain," and the twelfth in the Delta was named after the god Thoth.

Each nome possessed its coat-of-arms, derived either from its name or its religious myths; this was borne on a pole before the chieftain on solemn occasions. The shield of the hare province explains itself; that of the eighth nome was Jg , the little chest in which the head of Osiris, the sacred relic of the district, was kept. The twelfth province had for a coat-of-arms, signs which signify “his mountain ".

Nome Government

The nomes were headed locally by nomarchs. In the same way as the nome was a state in miniature, its government was a diminutive copy of the government of the state. ' The nome also had its treasury, and the treasurer, who was an important personage, had the oversight of all the artisans, the cabinetmakers, carpenters, potters, and smiths, who worked for the nomarch. He even built the tomb for his master, and he was so highly esteemed by the nomarch that he was allowed to travel in the boats with the princes. There were also the superintendent of the soldiers, who commanded the troops of the nome, the superintendent of the granaries, the superintendent of the oxen, the superintendent of the desert, a number of superintendents of the house, and a host of other scribes and officials. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A tomb illustration shows us part of the government offices of Khnumhotep; they are in a court which appears to be surrounded by a wall. The building on the left is the treasury, in which we see the weighing of the money that has just been received. The treasurer Bak'te squats on his divan inspecting the work, whilst, outside, his scribe, Neternakht, makes a record of the proceeding. Close by is the building for the “superintendence of the property of the revenues," and here the scribes are especially busy. The harvest is just over and the grain is being brought into the granaries; each sack is filled in the sight of the overseer and noted down, and when the sacks are carried up the steps to the roof of the granary, the scribe Nuteruhotep receives them there, and writes down the number emptied through the opening above. In this way any peculation on the part of the workmen is avoided, and the officials check each other. The nomarch is thus surrounded by a court en miniature, and like the king he has his “speaker," who brings him reports on all subjects.

During the time of the Middle Kingdom, owing to the independent position of the nomarch, the constitution of the state had become looser, but on the other hand one department of the government, a department centralised even during the Old Kingdom — the superintendent of the royal treasury and property, remained unchanged. In fact most of the high officials interred in the burial-ground of Abydos belong to this department, which at this time was held in even greater honour than ever. It formed apparently the central point of the state. We find a whole list of “houses “with their superintendents ; they are the bureaus, the writing and account rooms, of the different government departments, and it was the duty of their overseers "to reckon up the works, to write them down by the thousand, and to add them together by the million. "

The old office of "superintendent of granaries" is now called “the house of the counting of the grain," and the director takes a high position. " The supervision of the oxen, or the “house of the reckoning of the oxen," is placed under the “superintendent of the oxen", who also bears the title of “superintendent of the horns, claws, and feathers. " The “supervision of the storehouses “" is often combined with the latter, and finally there is also the finance department, the house of silver of the Old Kingdom, called also the “great house. " This last department appears to have been the most important of all, and to have even included the others, such as we sometimes find the supervision of the storehouse and of the oxen subordinate to the treasury department.

Village Chiefs in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Old Kingdom funerary iconography usually depicts the chiefs of villages bowing to, or being beaten by, higher authorities to whom they are mere bearers of tribute and taxes. In some instances, as in a famous scene in the 18th-dynasty tomb of Rekhmira, the quantities of cloth, precious metals, and other goods the chiefs carried were carefully recorded. When the authority of the monarchy collapsed, however, village chiefs appear in a more positive light, as repositories of authority and resources, and as links to social networks that provided protection for their communities. In a total reversion of roles, it was then that scribes and administrators proudly proclaimed that they served under these chiefs. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Leaving aside these rather biased claims, administrative texts mention village chiefs as indispensable mediators for implementing orders of the king. Apparently this role was sometimes materially rewarded, as some of these local leaders managed to afford for themselves prestigious items (such as statues and inscribed objects, usually reserved for officials and the elite) that marked their local preeminence. To their subordinates and the people living under their jurisdiction they acted as patronage leaders and sources of authority, probably based on a mix of prestige, family origins, wealth, and traditional authority . In late third and early second millennium BCE Elephantine, for instance, the local elite appear as a reduced but closely knit social group, in which rituals and ceremonies, veneration of a(n ideally) common ancestor, and the mutual exchange of goods in funerary rituals helped maintain their cohesion as a social group as well as their position and prestige as rulers of their community. In fact, it was from this group that governors and other local leaders were issued.

“Having left practically no written trace about themselves, it appears that village chiefs were basically local potentates and wealthy farmer s, closely connected to local temples. Texts from the first millennium BCE refer to them a s “big men,” in control of their communities. A Demotic literary text gives some clues about their power, when one such “big man” kept close ties to the local temple that further strengthened his authority. He was also a priest in the local temple —a function that provided him with a profitable source of income. He received part of the agricultural income of the sanctuary because of his service as a priest and, in addition, he exploited some temple fields as a cultivator in exchange for a portion of the harves t; the considerable wealth thus amassed allowed him to pay wages to the personnel of the temple, who were thus considered his clients (the text states that he had “acquired” them) and he could even marry his daughters to priests and potentates (lit. “great men”) of another town.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Microhistory by Juan Carlos Moreno García escholarship.org

Royal Administration of Villages in Ancient Egypt

royal official

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The relations of the villages with the royal administration are the best documented aspect of their existence. The most ancient records state that villages could be granted to high officials and members of the royal family as a reward for their services; in fact, the papyri of Gebelein deal with some villages, which formed one part of such rewards, the pr-Dt, “house of the body,” of an unknown official in the late 4th Dynasty. Nevertheless, these papyri also reveal that the villagers had obligations to many contributions to the royal administration, including working on architectural projects. Later documents such as the Horemheb or the Nauri decrees show that royal agents could make requisitions of manpower in villages and force their governors to deliver goods at the mooring posts, to cultivate the land of the pharaoh, or to accomplish corvée services for the temples. Other deliveries included cloth, animals, and gold, as the “taxation scene” in the 18th Dynasty Theban tomb of Rekhmira, the Amarna Period talatat, or the Ramesside administrative documents show; villages could also be taxed with specific supplies for a cult. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Nevertheless, the main contribution of villages was manpower. Old Kingdom sources evoke many administrative bureaus, which could request workers from Upper Egypt and which kept lists of men liable to be conscripted. The Gebelein papyri are a good example of such lists, while the decrees of Coptos suggest that villagers were recruited to work at a local estate of the temple of Min. The stone marks in the mastaba of Khentika at Balat also show a system whereby people from different localities successively carried the blocks to be used in the monument. Texts of the Middle Kingdom, like the Reisner and Lahun papyri, the stone marks in the pyramids of the kings, or the Hammamat inscriptions describe in detail the local organization of teams of workers, their conscription, and the role played by the governors of the villages in their recruitment.

“Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to determine the impact of such requisitions on the local economy and the domestic life cycle (partial dependence of villagers on the ration system, manpower diverted to the administration demands, obligation to produce specific crops and goods, incorporation of poor people into the “state sector,” etc.), not to mention on village society (reinforcement of the power of the local elite, opportunities for ambitious individuals, increase of inequalities). The crisis of the central authority at the end of the Old Kingdom, for example, was followed by an increase of wealth in private provincial tombs, a fact that could be linked to less fiscal pressure but also to the “reinvestment” of resources in the local sphere. Perhaps the mentions of uncultivated land and extensive cattle breeding in the contemporaneous el- Moalla and Deir el-Gabrawi inscriptions point to an alternative model of production, less dependent on intensive agriculture and only possible when the fiscal impact of the state weakened or simply vanished.”

Granaries and Local Administration in Ancient Egypt

Nadine Moeller, a University of Chicago archaeologist and director of the excavation at Tell Edfu, and her team have excavated the equivalent of the town square in a provincial capital, south of ancient Thebes (modern-day Luxor). Alen Boyle wrote in Cosmic Log: “Among the most intriguing structures excavated so far are seven grain bins dating back to the 17th Dynasty (1630-1520 B.C.). Because grain served as a form of currency, this wasn’t merely a granary – it was also the ancient equivalent of a bank, essentially managing tax collections for the provincial governor and the pharaoh. “Grain as currency provided the sinews of power for the pharaohs,” Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, said.[Source: Alen Boyle, Cosmic Log, July 1, 2008 |+|]

“The administration of that power has been described in ancient Egyptian texts, but there’s nothing like seeing the actual places where that power was exercised. The silos measure 18 to 21 feet wide, making them the largest grain bins ever discovered within an ancient Egyptian town center. Yet another layer of construction predated the silos. Moeller and her colleagues determined that a mud-brick structure with 16 wooden columns was used in the 13th Dynasty (1773-1650 B.C.), based on an analysis of shards of pottery and scarab seals found at the site. The hall of columns served as a place where scribes did their accounting, opened and sealed containers, and received letters. |+|

“Moeller speculated that the hall may have been part of the provincial governor’s palace. “It was far more extensive than we expected,” she said. “Actually, I still haven’t reached the full limit of the whole structure.”“ |+|

Sennefer, the Mayor of Thebes

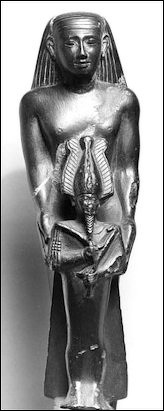

Sennefer and his family

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Sennefer was the mayor of Thebes during the reign of Amenophis II (c.1427-1400 B.C.), near the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty. His life is known mainly from his remarkable painted tomb on the west bank at Luxor. The burial-place of Sennefer is known as the Tomb of the Vines. This is because of its most distinctive feature-the ceiling of the main chamber is left irregular, painted over with bunches of grapes. The effect makes viewers feel they are looking up under the canopy of a cool vineyard. It is no surprise that Sennefer's proudest title is that of Overseer of the Gardens of Amun. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Amun was the god of Thebes, with his principal sanctuary at Karnak .The ruins of this place eventually covered an area the size of the financial City of London. In Sennefer's day it had not reached this size but was still impressive, with correspondingly grand gardens. A vignette of part of the estate occupies one wall of the Tomb of the Vines. It was walled, reached by means of a waterway, with tunnels of trellised vines separating different gardens. The text accompanying the picture ascribes the building of the garden to the ruling monarch, who would certainly have approved such a project, but the inspiration would have been Sennefer's, as is confirmed by the ingenuity that went into the design of his tomb. |::|

“Sennefer, whose other title is Mayor of Thebes, is shown on the pillars of his tomb wearing an amulet in the form of a double heart, inscribed with the name of his sovereign. This indicates his loyalty to his king, and his position as a royal favourite. Until forty years ago, Sennefer was known only from his statue in the Cairo Museum, and his exquisite tomb. But he has also come to light in a letter written on papyrus (now in Berlin) to an estate manager. Letters from this period are rare, and those that drop their official mask and reveal an individual are even rarer. Hectoring of the sort shown here is characteristic of Egyptian officials, and can even be affectionate. It is the passionate sincerity of the letter that really counts. |::|

“A note on the reading: The precise meaning of the Egyptian word wiwi is unknown, but it is clear that Sennefer thinks that his tenant is ineffectual in some way. Cusae and Hu were towns on the river to the north of Thebes. The letter was intended to dismay poor Baki, but he never read it. The letter was found still rolled up and sealed, as it was when it was sent more than thirty centuries ago. |::|

“The letters, temple carvings and coffin inscriptions of ancient Egyptians offer us an insight into the private life of an extraordinary civilisation. The collection of readings performed here range across 3,000 years; they include a letter from a king, a princess's prayer and the dream of a temple dancer. These are the testimonies of real people, citizens of ancient Egypt; some important, others less so, but all very much alive in the words that survive them.” |::|

Sattjeni, Wife a Governor and Member of the Ancient Egyptian Elite

A coffin, discovered in 2016 in the necropolis at Qubbet el-Hawa across the Nile River from Aswan by a team led by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, an Egyptologist at the University of Jaén in Spain., belonged to an important local woman, Sattjeni, daughter of one governor, wife of another and mother of two more. Sattjeni's mummified body was buried in two cedar coffins made of wood imported from Lebanon. She was not a royal, but her family practiced royal strategies to hold on to their governing power: She married her sister's widower, and her family was associated itself with the ram-headed deity Khnum. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, June 6, 2016 |~|]

Jiménez-Serrano told livescience: “Qubbet el-Hawa is one of the most important nonroyal necropolises of ancient Egypt. Its importance lies in the great quantity and quality of the biographical inscriptions carved in the façades of the funerary complexes. The necropolis was mainly used to bury the highest officials of the nearby town of Elephantine, the capital of the southernmost province of Egypt, at the end of the third millennium and the beginning of the second (2200 B.C. to 1775 B.C). The governors were buried together with their relatives; the members of their courts (officials and domestic service) were buried in other smaller and less-decorated tombs. Thus, today, we know the existence of 100 tombs, of which only 80 have been completely cleared. |~|

“During the Middle Kingdom, especially during the 12th Dynasty (1950 B.C. to 1775 B.C.), the governors of Elephantine built giant funerary complexes in the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa. Some of them are beautifully decorated and have important inscriptions....Sattjeni was the second daughter of one of the most important figures of the 12th Dynasty, the governor Sarenput II. Unfortunately, her brother Ankhu died shortly after his father, and there were no male successors. So she and her sister Gaut-Anuket had the rights of the rule in Elephantine. The latter married a certain official called Heqaib and converted him into the new governor of Elephantine: Heqaib II. However, we suspect that Gaut-Anuket did not live much time, because Sattjeni married Heqaib II. They had at least two children, who became the governors of Elephantine successively, as Heqaib III and Ameny-Seneb. |~|

“This discovery shows that the local dynasties of the periphery of the State emulated the royal family. In this concrete case, we can confirm that women were the holders of the dynastic rights. Probably, the members of these families married as the royal family — brother with sister — in order to keep the divine blood "pure." We must not forget that Sattjeni's family declared themselves heirs of a local god.” |~|

Estates and Local Officials in Ancient Egypt

an official

Juan Carlos Moreno García of Université Charles-de-Gaulle wrote: “A third kind of domain was formed by the landed possessions held by royal officials as remuneration for their services. Little is known about the standard estates allotted to each category of official (the categories having been based on an individual’s rank, function, and status). [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, Université Charles-de-Gaulle, France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Some agents of the king boasted in their autobiographical inscriptions of the (presumably exceptional) estates granted to them by the king to reward them for their outstanding services: Metjen (4th Dynasty) was rewarded with fields of variable dimensions for his activities as governor of several royal administrative centers (Hwt and Hwt-aAt) in Lower Egypt; Sabni of Elephantine (6th Dynasty) was nominated as xntj-S (an honorific court title) of a royal pyramid and was granted a field of about eleven hectares after a successful mission in Nubia; and Ibi of Deir el-Gabrawy (6th Dynasty) received a field of about fifty hectares linked to a Hwt. It seems doubtful whether the descendants of an official could have inherited the estates granted in this way. Members of the royal family (especially the royal sons) were possibly an exception, as their property was administered by a special administrative branch: the Overseer of the Provinces of Upper Egypt Kapuptah (5th Dynasty), for example, was also Overseer of the Property of the Royal Sons in the Provinces of Upper Egypt (jmj-r jxt msw nzwt m zpAwt Smaw), whereas Ankhshepseskaf (5th Dynasty) was Overseer of the Estates of the Royal Sons (jmj-r prw msw nzwt), a title also borne by his contemporary, the vizier Senedjemib-Inti; and prince Nykaura, a son of pharaoh Khafra, distributed his many estates among his wife and children while he was alive, although it is not certain that his instructions were also valid after his death. Some royal decrees, as well as the papyri from the royal funerary complexes of Neferirkara and Raneferef, show that the nomination of an official as xntj-S of a royal pyramid was an important source of income that included both offerings and agricultural estates. But access to these coveted honors was restricted, as the decrees in the Raneferef archive proclaim.

“The granting of estates as remuneration or reward to the officials of the kingdom was so widespread that an iconographic motif arose in private tombs depicting processions of offering bearers accompanied by place-names that supposedly represented the estates possessed by the tomb owner. However, these place-names seem to have been for the most part fictitious, used mainly as a decorative device emulating the ideal landscape governed by the king, a landscape represented in the funerary monuments of the king himself: the precisely symmetrical depiction of estates on the walls of the tombs (even in cases where the offering bearers bore no name), the absence of any information about virtually all these alleged place-names (even in the tombs of the heirs of the original owners), and the representation of exactly the same number of estates in both Upper and Lower Egypt suggest that this iconographic motif was not intended to depict the estates actually granted to an official.”

Family Served as a Social Safety Net in Ancient Egypt

Based on texts found at Deir el-Medina, a village of artisans near the Valley of the Kings, Anne Austin wrote in the Washington Post: In cases where these provisions from the state were not enough, the residents of Deir el-Medina turned to one another. Personal letters from the site indicate that family members were expected to take care of one another by providing clothing and food, especially when a relative was sick. These documents show us that caretaking was a reciprocal relationship between direct family members, regardless of gender or age. Children were expected to take care of both parents just as parents were expected to take care of all of their children. [Source: Anne Austin, Washington Post, February 17 2015. Anne Austin is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University ***]

“When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community. ***

“This shows us that health care in Deir el-Medina was a system with overlying networks of care provided through the state and the community. While workmen counted on the state for paid sick leave, a physician, and even medical ingredients, they depended equally on their loved ones for the care necessary to thrive in ancient Egypt.” **

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024