STONE TOOL MANUFACTURING IN ANCIENT EGYPT

ancient Egyptian surgical tools

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “The amount of work a knapper invested in making a tool was dependent on the length of time it could be expected to be used. Axes which received harsh treatment and therefore broke quickly were generally fashioned with a few well-placed strokes. The heads were fastened to the handles by cutting a socket into the wood, inserting the blade and tying it with a cord two or three feet in length. No cement was used.

“Broken tools were often reshaped and dull edges resharpened. Axe heads were sometimes ground down to such an extent that little stone was left protruding from the socket, before they were discarded. Knapping was quite a difficult craft and became specialised in pre-historic times. Workshops producing stone tools have been found in 4th millennium Hierakonpolis.

“The advancing bronze age saw a decline in the frequency of use and quality of stone tools, not just because metal displaced stone but possibly also because the best craftsmen preferred the material which offered the more interesting possibilities. Bronze tools must have been significantly more expensive than flint and therefore less affordable. Knapping, a specialized profession once, probably became one of the tasks which labourers who were not very expert at it but too poor to be able to purchase metal tools, had to perform of necessity. The quality of the stone had deteriorated as well. Deposits closer-by were being exploited despite the poor quality of the flint. But the knowledge of manufacturing basic stone blades continued until Roman times.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”The Production, Use and Importance of Flint Tools in the Archaic Period and the Old Kingdom in Egypt” by Michał Kobusiewicz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: Ground Stone Tools, Rock-cut Installations and Stone Vessels from Prehistory to Late Antiquity” by Andrea Squitieri and David Eitam (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries” by A. Lucas and J. Harris (2011) Amazon.com;

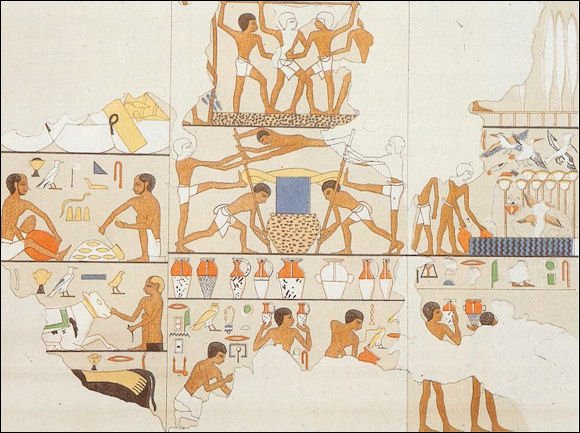

“'Make it According to Plan': Workshop Scenes in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom” by Michelle Hampson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Metalworking and Tools” by Bernd Scheel (1999) Amazon.com;

“Old Kingdom Copper Tools and Model Tools” by Martin Odler (2017)

Amazon.com;

“Tools, Textiles and Contexts: Investigating Textile Production in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age” by Eva Andersson Strand and Marie-Louise Nosch (2015) Amazon.com;

“Commerce and Economy in Ancient Egypt” by Andras Hudecz (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Economy: 3000–30 BCE” by Brian Muhs (2018) Amazon.com;

Dynastic Period Stone Tool Production

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: “Larger, Old Kingdom assemblages of knapped stone tools were also discovered at Giza, and the importance of the flint sickle for the agrarian society of ancient Egypt is mirrored at sites such as Kom el-Hisn. From Ain Asil in the Dakhla oasis comes an assemblage from the second half of the third millennium B.C. that features a high amount of scrapers, indicating a special task such as hide processing. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The use of flint tools continued throughout the second millennium B.C. as the raw material was cheap and plentiful and thus more affordable and accessible than metal. The tomb of the nomarch Amenemhet at Beni Hasan (BH2) of the 12th Dynasty has a scene showing the mass production of flint knives by men. In wall decoration, the shape of the knives of the Old Kingdom, the First Intermediate Period, and Middle Kingdom look very similar. They have a straight back and a convex cutting edge. However, in most cases the handles were more elaborate in the Old Kingdom.

“A fine lithic sequence from the Middle to the New Kingdoms can be studied at the sites of Tell el-Daba and Qantir in the eastern Nile Delta. Lithic assemblages are also known from the New Kingdom capital at Tell el-Amarna. Right down to the first millennium B.C., flint was used as a raw material for implements such as arrowheads. The finds in the royal tombs at el-Kurru are a good example of this. The specialized craftsmanship of flintknapping probably came to an end in the first millennium B.C..

Stone Tool Materials in Ancient Egypt

flint knives

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “The three most common rock types used for these purposes were chert, dolerite, granite, metagraywacke, and silicified sandstone. A total of 21 ancient quarries are known for these stones...Chert was the material of choice for most stone tools as early as the Palaeolithic and continuing through the Dynastic Period. This rock consists of microcrystalline quartz and occurs as nodules in limestone. The terms “chert” and “flint” are variously and inconsistently defined and, for the purposes of this article, are treated as synonymous. Ancient Egyptians referred to chert as ds kilometers (des kem) when it was dark brown or gray, ds HD (des hedj) and ds THn (des tjehen) when of lighter color, or sometimes simply as ds (des). Chert was one of the toughest stones available to the Egyptians and had an abrasion (or scratch) hardness superior to that of all the metals, including the best quality iron. It was easily shaped by knapping, but its principal advantage was its ability to provide tools with a sharp, durable edge. It was therefore widely employed for all types of cutting blades, especially knives and sickle teeth, as well as adzes, awls, axes, burins, drill bits, pick heads, and scrapers, among others. Although chert was used throughout the Dynastic Period, the variety of tools and quality of workmanship declined over time as the use of metals increased, with only chert knives and sickle blades remaining relatively common until the Late Period. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Chert is common wherever limestone occurs, which is in the Nile Valley walls and on the adjacent desert plateaus between Cairo in the north and Esna in the south. There were undoubtedly many ancient chert quarries but relatively few of these have been reported. From Palaeolithic to Predynastic times chert cobbles were extracted from pits dug into gravel deposits on the Nile River terraces of Middle Egypt, and at Ain Barda in the Eastern Desert’s Wadi Araba. Pits were also dug into chert-bearing weathering deposits on top of the limestone in the Refuf Pass area of Kharga Oasis during the Predynastic Period. It was, however, probably more commonly the case in these early periods that chert was not excavated but merely harvested from natural surface accumulations of already loose pieces of rock. Such sources are often referred to as “quarries” in the archaeological literature, but this is a misnomer, as no significant digging occurred. It was only during the Dynastic Period that chert nodules were quarried directly from the limestone bedrock.

“Dolerite is a black igneous rock that is compositionally similar to basalt but coarser grained. It was the favored material for pounders (also called mauls and hammerstones), which broke and crushed rock through blunt force. Pounders were used in quarrying hardstones, such as Aswan granite and many other ornamental stones, and also in mining gold and other metals. They were additionally employed for sculpting the same hardstones into architectural elements, statues, sarcophagi, stelae, vessels, and other objects. Pounders were largely replaced by iron tools (hammers, picks, chisels, and wedges) toward the end of the Late Period, but they continued to be used whenever metal tools were either unavailable or too costly. The smaller pounders were usually elongated pieces of stone with a narrowed waist where a wooden handle was affixed with leather strips. The larger pounders, commonly up to 30 centimeters across but sometimes larger, were unhafted and so hand- held. In their most familiar form, these are well-rounded, subspherical balls.

Source Materials for Stone Tools in Ancient Egypt

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “Macrocrystalline vein quartz derived from igneous and metamorphic rocks occurs abundantly in all parts of Egypt as surface pebbles and cobbles, and was commonly used for the same tools as chert, as were also a variety of other hard, fine-grained rocks, especially silicified sandstone. None of these stones, however, was used to the same extent as chert. Only obsidian (volcanic glass) imported from southern Red Sea or Eastern Mediterranean sources produced tools with a sharper edge, but it was much more brittle as well as more costly, and so was little used. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

Of the four true quarries known, the most important is in Wadi el-Sheikh near el- Fashn. Here the workings extend 7 kilometers along the north side of Wadi el-Sheikh, making this one of the largest quarries of any rock type to survive from ancient Egypt. It was active from the late Predynastic Period to the New Kingdom, but most of the workings visible today apparently date to the Old and Middle Kingdoms. The thousands of quarry pits and trenches, which are dug into the cherty limestone bedrock, range from a few to several tens of meters across and are surrounded by spoil piles up to a few meters high. In one part of the quarry, the pits drop into vertical shafts up to 8 m deep, and these branch out at the bottom into horizontal tunnels. Other tunnels penetrate the limestone along its exposed edge on the wadi walls. The principal products of the quarry were bifacial blades used for knives and axes, and thin trapezoidal blades used for sickle-teeth and also perhaps as general-purpose cutting tools. About 12 kilometers to the southeast of Wadi el- Sheikh is a similar but smaller chert quarry on the mesa tops along the north side of Wadi Sojoor. This site is largely unstudied, but the many workings, based on the chert tools found, appear to date to the Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom.

“The other two known Dynastic chert quarries date to the New Kingdom. A small one, which was also worked in the Predynastic Period, occurs on a hillside near Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt, but a larger and more important site is found in the Eastern Desert’s Wadi Umm Nikhaybar. The latter, not yet published outside of the present article, dates to the Ramesside Period and has two large trenches (25 - 28 m long, 3 - 4 m wide, and 2 - 2. 5 m deep) cut into the cherty limestone bedrock. Near these is a nearly square, fortress-like building with massive enclosure walls measuring 18 by 21 m. Only trapezoidal blades and the cores they were struck from are found in the knapping area beside the large building; the blades thus appear to be the principal, if not only, product of the quarry.

Although still debated, it seems likely that this shape was acquired through long use, the original tools having started as angular, irregular to subrectangular pieces of rock. Although the majority of pounders were of dolerite or its metamorphic equivalent, metadolerite, some were also of fine-grained granite from Aswan, silicified sandstone from near Aswan and Cairo, and anorthosite gneiss from near Gebel el-Asr in the Nubian Desert. The latter three rocks were also used as ornamental stones. What all these materials have in common is a high resistance to impact fracturing, dolerite being the most durable. Although there were probably many dolerite quarries for pounders, only three are known (two probable and one definite), and these are in Aswan. The one definite quarry is near Gebel el-Granite and is located on a small metadolerite outcrop. Here there are numerous places where both the bedrock surface and loose boulders on top of it have been worked, and beside each of these areas is a pile of angular pieces of metadolerite that are new pounders. These range from about 10 to 30 centimeters across, with most between 15 and 25 cm. Littering the ground, and in places forming a nearly continuous pavement, are metadolerite chippings, which are the by-product of the production of the pounders.

Utilitarian Stones in Ancient Egypt

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “The utilitarian stones of ancient Egypt were those rocks employed for implements and other mundane articles. Most of these fall into three categories: 1) tools for harvesting, food preparation, and stone working; 2) weapons for hunting, war, and personal protection; and 3) grinding stones for cereals and other plant products, ore rocks for gold and other metals, and raw materials for paint pigments and cosmetics. “The most common utilitarian stones were chert (or flint), dolerite, granite, metagraywacke (or graywacke), and silicified sandstone (or quartzite), but others were sometimes used as well (especially limestone and vein quartz). A total of 21 ancient quarries are known for these stones [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

Rocks were also used for other ordinary purposes, especially for weights (e.g., loom and net weights, plumb bobs, boat anchors, and measuring weights for balances). Objects from the first two categories, when produced by knapping (i.e., percussion and pressure flaking), are collectively referred to as “lithics.”

The stones exploited for tools and especially weapons were progressively supplanted by metals, initially copper in the late Predynastic Period, then the harder bronze beginning in the Middle Kingdom, and finally the still harder “iron” (actually low- grade steel) by the end of the Late Period. These metals, however, never completely replaced the stone tools and weapons, and crushing and grinding were almost always done with stones throughout antiquity.

Grinding Stones and Milling in Ancient Egypt

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “Grinding stones (also known as “mill” or “quern” stones) were widely used in all periods of Egyptian history for processing cereals (mainly emmer wheat and barley) and other plant products (those for unguents, perfumes, and other oils, or juices). They were also employed for crushing gold, copper, and other metallic ore rocks prior to smelting. Essentially any hard rock can serve as a grinding stone but, in the case of those used for plant products, there was a strong preference for silicified sandstone during the Predynastic and Dynastic Periods and vesicular basalt in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods . Coarse-grained granite from Aswan was additionally used in all periods. This chronological division is also exhibited in the grinding stones’ basic form. In Predynastic and Dynastic times, grinding stones consisted of a large stationary lower stone that was elongated and typically ovoid (often described as “boat-shaped”) with a flat (when new) to concave (when worn) upper surface. A smaller, hand-held upper stone (a “rider” or “rubber”) was pushed back and forth across the lower stone. The terms “mono” and “matate,” derived from Mesoamerican archaeology, are also sometimes applied to the upper and lower parts, respectively, of this so-called “saddle” hand-mill. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Two Greek innovations in cereal grinding technology were introduced into Egypt during the Ptolemaic Period: the “hopper-rubber” and “rotary” hand-mills. Both continued in use during Roman times along with the more primitive saddle hand-mills. The hopper-rubber hand- mill, also known as a “Theban hand-mill” (a translation of its ancient Greek name), had a rectangular upper stone into which were cut a trapezoidal grain hopper with a basal slit, and two lateral slots on top. A wooden cross-piece set into the slots served as a handle to push and pull the upper stone across a flat, usually rectangular, lower stone. Holes were sometimes cut into the sides of the upper stone for the insertion of handles . The upper and lower grinding surfaces were commonly incised (“dressed”) with parallel grooves to enhance the grinding action. The hopper-rubber hand-mills found in the Nile Valley and Fayum were commonly made from coarse- grained Aswan granite, but at Eastern Desert sites other similarly hard, local rocks were also employed. The rotary hand-mill, usually made from vesicular basalt but also occasionally from coarse-grained granite and silicified sandstone, arrived in Egypt late in the Ptolemaic Period. This mill type had a stationary circular lower stone with a central conical spindle, and a matching circular upper stone with an axial hole that fit over the spindle. The upper stone was hand-cranked with a wooden handle, set in a hole cut into one side, while grain was fed into the central opening.

“Rotary motion in milling was not only more efficient than the reciprocating motion of the saddle and hopper-rubber hand-mills, but it also allowed for larger mills that harnessed greater power sources. In Egypt during the Roman Period, this led to the first industrial- scale processing of cereals and other agricultural products as exemplified by the “horizontal rotary” and “edge-roller” mills. The former mill type consisted of a matched pair of large circular grinding stones, typically of coarse-grained Aswan granite. The lower stone was stationary while the upper (“runner”) stone turned around a wooden or metal spindle with a lever attached to either the runner or the spindle if the latter was socketed into a square axial hole in the runner. Grain was fed into the upper axial hole while the runner was rotated, via the lever, by either human or animal power. The edge-roller mill, in contrast, consisted of a circular stone (either large or small, and sometimes a pair of such stones) that rolled upright on its outer edge around a circular stone trough. A wooden lever passed horizontally through the axial hole of the upright stone and attached to a vertical spindle piercing the stationary trough, and this lever was then turned in the same manner as that of the horizontal rotary mill. Whereas all the aforementioned reciprocating and rotary mills ground materials by shearing them, the edge- roller mill merely crushed them, and because of this was especially popular for pressing olives and grapes. The absence of rigorous grinding also meant that softer stones, such as limestone, could be used for edge-roller mills.

“The granite and silicified sandstone used for grinding stones are the same rocks that were also employed as ornamental stones and no doubt came from the same quarries. The vesicular basalt preferred for rotary hand-mills does not occur in Egypt, but there are many potential sources in both the southern Red Sea and Eastern Mediterranean regions. Limited geochemical analyses suggest that at least some of the rock came from volcanic islands in the southern Aegean Sea . The extra expense incurred by basalt’s importation was not a deterrent to its use because it had a highly desirable feature: abundant, large vesicles (originally gas-filled cavities in the lava precursor of this volcanic rock). The edges of these vesicles act like cutting blades and are continuously sharpened as the stones wear down. To a lesser degree, the same process operates with silicified sandstone, which has smaller open pore spaces between its sand grains. The same cutting action can be achieved in Aswan granite or any other hard rock when the grinding surfaces are cut with parallel grooves, the edges of which function as cutting blades.

“The same chronological dichotomy of reciprocating and rotary grinding stones for plant products applies to the reduction of ore rock from mines. The stones used, however, were just the locally available hard rocks and so vary from one site to another. A well- documented evolution in grinding stone technology exists for the gold mines in Egypt’s Eastern Desert and Sudan’s Nubian Desert. Prior to the New Kingdom, ore rock was reduced through direct crushing by pounders on stone anvils. It was during the New Kingdom that the familiar reciprocating grinding stone ensemble was introduced. The lower stone originally had a flat surface and then developed an oval depression with use. This, with the accompanying upper (rubber) stone, has been referred to as an “oval” or “dished” hand-mill. The next big innovation occurred in the Ptolemaic Period, when the so-called “saddle quern” was used. This had an originally downward-curving lower stone (which became more deeply concave with use) and a massive, subtriangular upper stone with two lug handles. This unique form of hand- mill was also employed to a limited extent for grain during the Ptolemaic Period. The final development, in the Roman Period, was the rotary hand-mill that was larger but otherwise similar in form to those of vesicular basalt used for grinding cereals. Regardless of the method of grinding, the ore rock was pre-crushed to about pea- size on either a stone anvil or in a stone mortar.

“Other types of grinding (and crushing) stones employed in ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period onward were the mortar and pestle, along with their primitive counterparts, and the pounder (often of white vein quartz) and anvil (of any hard rock), as well as the so-called “palette,” which was used principally during the late Predynastic and

Dynastic Periods. Whereas a wide variety of materials were ground with mortars and pestles, palettes were apparently only used for the preparation of cosmetic eye shadow or kohl, usually powdered green malachite or dark gray galena. The palettes are sometimes elaborately decorated with relief carvings, such as those on the famous Narmer Palette of the 1st Dynasty from Hierakonpolis, now in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. In this case se, and in many other examples, the palette seems more of a votive or ceremonial object than a working grinding stone. Many of the more ordinary palettes have zoomorphic outlines , but other shapes also occur. Essentially all palettes were fashioned from grayish-green metagraywacke (commonly misidentified as “slate” or “schist”), one of the principal ornamental stones of ancient Egypt.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024