Home | Category: Religion and Gods

AKH

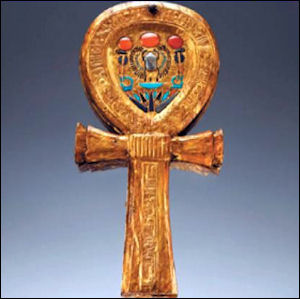

Ankh mirror from

Tutanchamun'sTomb Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The notion of akh, often translated as (effective) spirit, pointed toward many different meanings, such as the identity of the transfigured dead as well as that of living persons who acted efficaciously for (or on behalf of) their masters. The akh belonged to cardinal terms of ancient Egyptian religion and hence is often found in Egyptian religious texts, as well as in other textual and iconographic sources. Its basic meaning was related to effectiveness and reciprocal relationship that crossed the borderlines between different spheres. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The akh is included among religious terms connected to the Egyptian conception of human and divine beings, their status, roles, and mutual relationships. Since it was linked to a wide range of ideas and beliefs at the core of ancient Egyptian religion, this term and its derivatives occur regularly in Egyptian religious texts, as well as in textual and iconographic sources of other character.

“Although the akh—like the words ka and ba—lacks an exact counterpart in any modern language, it has often been translated as “spirit”, leaving aside the impossibility to find exact counterparts for words in different languages. The Egyptian term, however, pointed toward many different but interconnected meanings, for instance, the ideas of the transfigured, efficacious, glorious, or blessed dead. The term akh also had to do with the notions of being an intermediator between the living and the divine (see below). The core meaning of akh had to do with the idea of “effectiveness” and mutual relationship or dependence that crossed the borderlines between the human and divine spheres, and between the world of the living and the realm of the dead.

“The Egyptians used a representation of the northern bald ibis for the hieroglyphic sign “akh”. The bird (as well as its ancient images) is easily recognizable by the shape of its body, posture, shorter legs, long curved bill, and a typical crest covering the back of the head. Although there are many aspects of this bird’s nature that must have had impact on the mind of the Egyptians—such as the glittering colors on its wings — the main factor in holding the bird in particular esteem and relating it to the concept of the akh was its habitat, since the northern bald ibis used to dwell on rocky cliffs that stretched out along the eastern bank of the Nile. It was the region that the Egyptians called the akhet, and considered the region of sunrise, rebirth, and resurrection. Therefore, these birds were connected with powers and beings believed to dwell within or behind the region of the horizon.

“Although recent research has shown that no primary link probably existed between the word Ax (akh) and the term jAxw (jakhu) meaning “light, radiance, or glow”, the akh was often connected with solar light and stellar brilliance, or even with the light-based creative power. K. Jansen- Winkeln has put forward the idea that the original notion of the akh and of its derivatives was linked to the mysterious, invisible power and efficacy of the sun at the horizon (e.g., akhet) during the dawn and the dusk when the light was visible although its source remained hidden.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Symbols: 50 New Discoveries” by Jonathan Meader and Barbara Demeter (2016) Amazon.com;

“Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art” by Richard H. Wilkinson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Manfred Lurker (1984) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt” by Robert Thomas Rundle Clark Amazon.com;

“Esoterism and Symbol” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (1985) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion” by Donald B. Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Egyptian Cosmology and Akhu

Ank, Djed and Sun

On Egyptian religion and cosmology and the akhu, Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The three levels or realms of created cosmos (the earth, the sky, and the underworld) converged at the horizon (akhet). The latter term represented the junction of cosmic realms, and it was also viewed as the place of sunrise, hence the place of birth, renewal, and resurrection. Moreover, it was considered a place where divine beings (both gods and the blessed dead) dwelt and from whence they could venture forth. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The notion of the akh has often been translated as “spirit” or “blessed dead,” though the range of its aspects and powers covered also the meanings of “superhuman power” or “sacred mediator”. The Egyptians considered their blessed and influential dead—the akhu—as “living,” i.e., as “the resurrected”; however, human beings had to be transfigured and admitted into this state. Finally, the akh represented a mighty and mysterious entity that was part of the divine world and yet still had some influence upon the world of the living. They could interact with the living by means of superhuman powers and abilities, guard their tombs, punish intruders or wrongdoers, help in cases when human abilities were insufficient, or act as mediators between gods and men.

“In a parallel with the gods and people, a certain hierarchy existed even within the society of spirits. The deceased king thus represented “the head of the akhu” (Pyramid Texts Spell 215, §2103). According to Egyptian cosmology and mortuary texts, the akhu were “born” or “created” at the horizon, where they also dwelled and where they came from. Some sources (e.g., the so-called Book of the Dead), thus, use an expression jmyu akhet (“those who dwell in the horizon”) to denote or describe the blessed dead. Since the akhu were dependent on ritual actions performed by the living, a mutual relationship and cooperation between men and akhu formed one of the pillars of ancient Egyptian religion.”

Gods, Akhu, and Men

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The Egyptians divided the cogitative beings of the world into different types or categories with regard to the degree of their power and authority. This concept occurred for the first time in Middle Kingdom texts and remained in use until the Roman Period. The division of the categories of beings appears also in the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead, as well as in hymns, ritual or educational texts, and onomastica. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The highest position among the beings was held by the gods (nTrw) and the lowest was reserved for human beings (rmT; occasionally subdivided into pat, rxyt, and Hnmmt), or rather the living (anxw tp tA). The boundary sphere between the human and divine worlds was believed to be operated by semi-divine entities or beings with super-natural status and power, such as the demons and the blessed and the damned dead (the Axw and the mwtw), and by the supreme intermediator, the king. Royal annals or king-lists, which sometimes record divine dynasties and rule of the akhu prior to the historical or at least legendary rulers, witness a very similar concept of hierarchy.

“As to the role of the akh among other terms relating to composites, parts, or manifestations of human and divine beings, unlike the body, the ka, the shadow, it was never believed to represent part of the composition of a human entity. The Egyptians considered their blessed, efficient, and influential dead (i.e., the akhu) as “living,” that is, as “resurrected.” According to Egyptian ideas on life, death, and resurrection, a person did not have an akh, he or she had to become one. Moreover, this posthumous status was not reached automatically. Human beings had to be admitted and become transfigured or elevated into this new state. The dead became blessed or effective akhu only after mummification and proper burial rites were performed on them and after they had passed through obstacles of death and the trials of the underworld. Thus, only a person who lived according to the order of maat, who benefited from rituals or spells called the sakhu—those which “cause one to become an akh” or the “akh-ifiers” —and was subsequently buried, could be glorified or become transfigured into an akh. Late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period offering formulae attest the idea that a person was made akh by the lector priest and the embalmer. After reaching this status, the dead were revived and raised to a new plane of existence. The positive status of the mighty and transfigured akhu was mirrored by a negative concept of the mutu who represented those who remained dead, i.e., the damned.

“From a cosmological point of view, the horizon (e.g., akhet) played a very important role in the process of becoming an akh. Although it mainly represented the junction of cosmic realms (the earth, the sky, and the netherworld), the horizon was a region in itself. The akhet was believed to be the place of sunrise, hence the place of birth, renewal, and resurrection, and, moreover, it was considered a region where divine and super-human beings dwelt and from whence they could venture forth. Thus, the horizon represented the very place of “birth” or “creation” of the akhu. In the Book of the Dead, the blessed dead were denoted as “those who dwell in the horizon”.

“Besides the above-mentioned moral and ritual prerequisites, one’s intellectual power and knowledge as well as his or her social status might have been important factors in reaching the akh-status. In a parallel to the world of the gods and human beings, a certain hierarchy and stratification existed even within the society of the akhu. Thus, the (deceased) king or Horus represented “the head of the akhu” (Pyramid Text §§ 833, 858, 869, 899, 903, 1724, 1899, 1913 - 1914, 2096, 2103) or was considered the first of the akhu, the “akh akhu”.”

Role of the Akh

Ankh

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “When a dead person’s journey to the afterlife had successfully finished and he/she was justified, transfigured into an akh, and resurrected, the person became a mighty and mysterious entity, which participated in the divine sphere of existence and yet still had some influence upon the world of the living. The akhu guarded their tombs where they promised to punish intruders on the one handand be inclinable to those who presented them with offerings on the other. But they also interacted with the living by means of superhuman powers and abilities: they could help in cases when human abilities were insufficient, as evidenced by the so-called Letters to the Dead, and acted as mediators who could intercede on behalf of the living with the gods or other akhu. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Although the akhu had reached the afterlife existence, they still needed the living, since it was the latter who performed rituals, carried out the embalming and funerary requirements, and provided their dead ancestors with offerings. Sus- taining the needs of the akhu is attested by a ceremony called “the feeding the akh” with the glorified deceased depicted in front of food offerings in the 4th and 5th Dynasty tombs at Giza. This ceremony was later incorporated into the Opening of the Mouth ritual. Later still, Ani in his Teachings reminds his audience that one should appease the akh with everything he desires, since that spirit is capable of doing all kinds of evil things.

“As for the above-mentioned “feeding of the akh” scene, some scholars have connected it to depictions attested on Early Dynastic cylinder seals where the šps- noble is represented seated opposite a head- turned akh-bird with an offering table in between them, and by doing so, traced the feeding of the akh ritual back to early periods of Egyptian history. Such interpretation is, however, still uncertain, as is the identification of the bird on these seals, since the depicted animal does not bear the main characteristic features of the northern bald ibis, and it thus would represent an unprecedented way of imaging this bird, unique both in Egyptian script and art. “The akhu and the living represented co- dependent communities, and their mutual relationships and cooperation formed one of the pillars of ancient Egyptian religion. And it was precisely the bilateral akh-efficient, reciprocal actions of both categories of beings, which crossed the threshold of death and the border of this and the next world. In this funerary context, the living son was efficacious and serviceable for/on behalf of his father, as much as the father was akh-efficient and beneficial for/on behalf of his son, besides being an akh himself. The son gained this status by providing his father with burial and offerings, as well as by assuming the father’s earthly position and authority, and the latter by legitimizing the son’s heritage and authority as well as by supporting and protecting him from the afterlife.

“This type of a mutual efficacy between father and son found its mythological model in the relationship between Osiris and Horus. As early as in the Pyramid Texts, Osiris is said to have become an akh (blessed, justified, glorified, resurrected, mighty, etc.) through the deeds of his son Horus; in the same way, Horus was believed to have become akh- effective and was legitimized by his father Osiris. A similar idea is attested also in the Book of the Dead Chapter 173 where Horus comes to Osiris to revive him with the embrace (of his ka), that is, to make him an akh.”

Power of the Akh

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: ““From the Old Kingdom onwards, the term akh often received an adjectival qualification within mortuary texts and tomb inscriptions. Thus, the akh could be mnx (proficient, potent), Sps (noble, venerable), but mainly jqr (excellent, competent) and apr (equipped). These expressions should describe the status and the power of the akh that were based on undergoing proper rituals, having proper tomb equipment and cult, and knowing proper spells or magic. Moreover, they should also draw attention towards his ability to act effectively for/on behalf of the living, since the akhu were both efficacious/helpful and influential. The efficacious power or competency of the akh was not restricted only to the above- mentioned bilateral, reciprocal relationship between two agents, mainly father and son, Horus and Osiris: it also covered a trilateral relationship where the akh functioned as a mediator, intercessor, or messenger between the living and higher super-human authorities, other akhu, and the gods. Using a word-play or pun as the Egyptians often did, we can say that a blessed, glorified deceased was believe to operate as an “akhtaché” of a divine authority among the living, who could intercede on behalf of his or her worshipers. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“From the Old to the Middle Kingdom, the living (both direct descendants of the deceased and the passers-by) could turn to the akhu in their tombs with offerings and spoken pleas, or even with requests written in “letters”. From the New Kingdom onwards, however, different media in this type of ancestor worship or private cult are attested: these include the so-called anthropoid ancestor busts and mainly the Ax iqr n Ra (akh jqer en Ra) stelae. The latter artifacts (attested from the late 18th Dynasty to the 20th Dynasty) showed the deceased person seated, usually with a lotus flower at his or her nose, and denoted him or her as an excellent akh, who is in a close relationship to the sun-god Ra and who can thus operate for/on behalf of him and intercede for/on behalf of worshipers. The akh was believed to have similar qualities and dispose with similar powers that have much later been ascribed also to angels in Greek magical papyri), ghosts in Coptic literature, and the saints in Christianity.

“However, the akh-effectiveness and its reciprocal relationship were not restricted to the sphere of the afterlife and to the mutual relationship between the living and the dead. Also the living of all social levels could become akh-effective on behalf of a higher earthly authority, or they could perform akhu-deeds for somebody. Thus, kings, officials, and townsmen could act with akh- effectiveness on behalf of their gods, kings, lords, or one another. The efficacious power of the akh was again connected both to the reciprocal relationship between father and son and to the trilateral relationship with the akh acting responsibly on behalf of a superior authority and helpfully for his petitioners.”

Akh-Relationship in the Amarna Period

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “Recent research has shown that the above- mentioned Ax iqr n Ra stelae probably had their direct precursors in the so-called “Family- stelae” of the Amarna Period that have been interpreted as media of religious practice rooted in ancestral worship with the king Akhenaten and his wife as Aten’s direct intermediators towards the people. Thus, the king was truly operating according to the proclamation of his new name, that is, as an (or rather the only) akh en Aten. Not only did he claim that he was akh-effective for/on behalf of his father Aten in the same way his divine father was akh for him, but he himself became a direct object of cult as Aten’s only intermediator, messenger, and image. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The importance of this concept is also strengthened by the fact that in the Amarna tombs we lack the former notion of the glorified and effective deceased (akh). The deceased are intentionally denoted almost exclusively as the righteous (mAatjw) or favored ones (Hsyw) there. The expression akh and the hieroglyphic sign of akh itself occur mainly within the name of the king or with regards to the relation between the king and the god. Other attestations speak about the earthly “akh- effective” and “serviceable” power of scribes and priests or about the akh-effectiveness of the deceased officials to their lord, the king. Similar akh- effective relationships of officials towards the king are attested, for example, in Parennefer’s Theban tomb or within an offering formula found in a private house in el-Amarna . A unique phrase was discovered among inscriptions in the tomb of Aye at el-Amarna: “You are first among the king’s companions, while similarly you are the first in front of the akhu” . W. J. Murnane translates the last term as “illuminated spirits,” however, in the light of the above-mentioned evidence on the akh reciprocity and relationship, we may assume that the expression was not endowed with its earlier mortuary meaning, but that it referred to Aye’s earthly position and his role as the highest official. Thus, priests and officials of the Amarna Period acted as akhu for/on behalf of the king, who himself operated and interceded as the akh of the supreme authority of Aten. The same officials, however, did not receive the status and function that was assigned to the glorified deceased prior to the historical period in question. They did not became the akhu who would act on behalf of gods and intercede on behalf of the petitioners, since this position was already occupied by the god’s sole earthly image, emissary, and intermediator, the king, as the sole akh of Aten.”

Akhu Power in Ritual and Magic

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “Besides the plural form akhu, a similar term (akhu as an abstract) is attested in Egyptian sources. It referred to akh-effective deeds, creative power of words, or ritual and magical spells . It also covered the aspects of secret knowledge and magical power of “invisible efficacy” possessed and operated by the gods, the deceased and magicians, or present in magical and medicinal texts. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“As was already mentioned above, the deceased were both respected and venerated for the akh-efficacious help they offered, but they were also feared for their power and for revenge they might bring. In this respect, the term akh referred not only to the deceased individual but also to his powers and potential manifestation. Usually, the living asked these mighty, effective, and influential deceased forhelp by cultic means (see above). However, in several attested cases, we read about the summoning of an akh-spirits to work for a magician or to speak to him, and there is also evidence for repelling of malevolent akhu and exorcisms, as in the case of the famous Bentresh Stela. These ideas on the nature, power, and function of the akh survived even within Coptic words, particularly the jkh (demon).”

Northern Bald Ibis — the Akh Bird

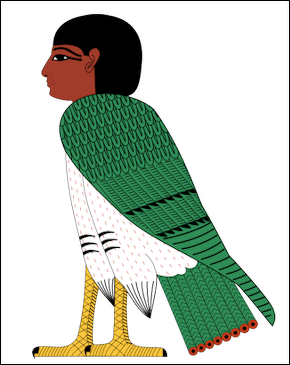

the ba bird, symbol of the soul

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “Three different kinds of ibis species are attested from ancient Egypt: the sacred ibis, the glossy ibis, and the northern bald ibis. Pictorial representations of the latter bird—easily recognizable by the shape of its body, the shorter legs, long curved beak, and the typical crest covering the back of the head—were used in writings of the noun akh and related words and notions (e.g., the blessed dead). We can deduce from modern observations that in ancient times this member of the ibis species used to dwell on rocky cliffs on the eastern bank of the Nile, that is, at the very place designated as the ideal rebirth and resurrection region (the akhet). Thus, the northern bald ibises might have been viewed as visitors and messengers from the other world—earthly manifestations of the blessed dead (the akhu). The material and pictorial evidence dealing with the northern bald ibis in ancient Egypt is accurate, precise, and elaborate in the early periods of Egyptian history (until the final phase of the third millennium B.C.). Later, the representations of this bird became schematized and do not correspond to nature. Thus, they do not present us with any direct and convincing evidence for the presence of the northern bald ibis in Egypt, and, moreover, they most probably witness both the bird’s decline and its disappearance from the country.[Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ] “As for the connection between the northern bald ibis and the akh, some scholars reached the conclusion that there was no (or only a phonetic) intrinsic relation between the two; others connected the root word akh with the term jakhu (“light, radiance or glow”) suggesting that the “glowing” purple and green feathers on the wings of the bird represented its link to the ideas of light, splendor, and brilliance. There are, however, scholars who have challenged the theory that the word akh was primarily connected with light and glare and suggested that the original meaning of the notions akh and akhu might have been linked, for example, to the idea of a mysterious, invisible force and to the efficacy of the sun at the horizon.

“Although there are many (probably secondary) aspects of the northern bald ibis’ nature that could have been important for the Egyptians such as, for example, the above- mentioned glittering colors on its wings, or its calling and greeting display, the main factor in holding the bird in particular esteem and connecting it with the akhu and the idea of resurrection was its habitat. This member of this ibis species used to dwell at the very place designated as the ideal rebirth and resurrection region (the eastern horizon as the akhet); moreover, its flocks might have very well represented the society of the “returning” dead. The ancient Egyptians saw migratory birds as the souls or spirits of the dead, and the fact that the northern bald ibis counts among the migratory birds might also have been very important. The arrival of these birds could have been a sign of the coming “spring” or the harvest season, as was the case at Bireçik. Thus, we find circumstantial evidence, which seems to support the theory that in ancient Egypt, the northern bald ibises were viewed as visitors and messengers from the other world and were earthly manifestations of the blessed dead.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024