Home | Category: Art and Architecture

LARGE SCULPTURES IN ANCIENT EGYPT

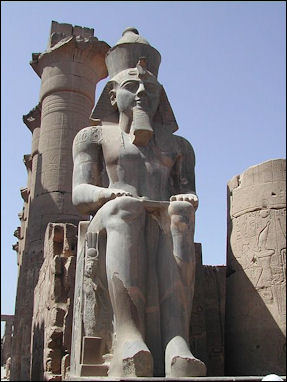

Ramses II Colossal statue The pharaohs commissioned rigid monumental statues to glorify themselves while they were still alive. The larger the state the more powerful the ruler. The most prolific pharaonic statue builder was Ramses the Great, whose likeness is found on colossi at Abu Simbel and other sites around Egypt.

"The art of portraiture very early created its own rigid conventions," the scholar Daniel Boorstin wrote. "Marks of a "grid" guided the sculptor at his work. It was long supposed that these were only a device commonly used by artists...for enlarging any small sketch. Then it was noticed that the squares always interesected bodies at the same places. These proved to be units of the canon of Egyptian sculpture."

"A standing figure comprised eighteen rows of squares (not counting the nineteenth row for the hair above the forehead). The smallest unit, the width of a fist, measured the side of a square. From wrist to elbow was three squares, from the slope of the foot to the top the knee was six squares, to the base of the buttock nine squares, to the elbow of the hanging arm twelve squares, to the armpit fourteen and a half squares. “

The Egyptian were never able to make free standing human sculptures. Either the figures were sitting down or coming out of a wall. When pharaohs and their queens were sculpted together the king usually wore a headdress and a skirt and his wife wore a tight fitting and revealing dress. Standing sculptures were characterized by clenched fists, rigid arms on the sides, two feet firmly on the ground with the left foot forward, but the body going nowhere.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SCULPTURE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS ANCIENT EGYPTIAN STATUES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

THE SPHINX africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Statues” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Statues: Their Many Lives and Deaths” by Simon Connor (2022) Amazon.com;

“Great Sculpture of Ancient Egypt” by Kazimierz Michalowski (1978) Amazon.com;

“The Mysteries of Abu Simbel: Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Sun” by Zahi Hawass (2001) Amazon.com;

“Colossal Statue of Ramesses II” by Anna Garnett (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sphinx: History of a Monument” by Christiane Zivie-Coche and David Lorton (2002) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Egyptian Art” by Émile Prisse d'Avennes (1991) Amazon.com;

“Highlights of the Egyptian Museum” by Zahi Hawass (2011) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum”

by Edna R. Russmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt At The Louvre” by Guillemette & Marie-Helene Rutschowscaya & Christiane Ziegler (trans Lisa Davidson). Andreu (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egypt and the Ancient Near East”

by New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Peter F Dorman, et al. (1988) Amazon.com;

Reliefs in Ancient Egypt — Closer to Painting or Sculpture

Reliefs show activities such as hunting, farming and battles. In Egypt we cannot, as we usually do now, reckon the art of relief as sculpture; it belongs from its nature to the art of painting or rather to that of drawing purely. Egyptian relief, as well as Egyptian painting, consists essentially of mere outline sketching, and it is usual to designate the development of this art in its various stages as painting, relief en creux (hollow relief) , and bas-relief If the sketch is only outlined with color, we now call it a painting, if it is sunk below the field, a relief en creux, if the field between the individual figures is scraped away, we consider it a bas-relief. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The style of drawing however is in all these cases exactly the same, and there is not the smallest difference in the way in which the figures are colored in each. At one time the Egyptian artist went so far as to seek the aid of the chisel to indicate, by modelling in very flat relief, the more important details of the figure; yet this modelling was always considered a sccondar) matter, and was never developed into a special style of relief.

Moreover the Egyptians themselves evidently saw no essential difference between painting, relief en creux, and bas-relief; the work was done most rapidly by the first method, the second yielded work of special durability, the third was considered a very expensive manner of execution. We can plainly see in many monuments how this or that technique was chosen with regard purely to the question of cost. Thus, in the Theban tombs, the figures which would strike the visitor first on entering are often executed in bas-relief, those on the other walls of the first chamber are often worked in relief en creux, while in the rooms behind they are painted.

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Sculptures

Ramses II Memphis Colossal statue Statues of the deceased called “ushabti” (shabtis) were placed in tombs next to the mummy. These were not intended for the public to see or as a memorial. They were a substitute for the person should something happen to the mummy, or they could be offered by the deceased as substitute if he was called on to do something unpleasant in the afterlife.

The sculptures were often made of stone with the understanding that that meant they could last for eternity. If something happened to the mummy the pharaoh's “ Ka” , or vital force, could move into the sculpture. Because they possessed ka, statues were regarded as powerful and even dangerous.

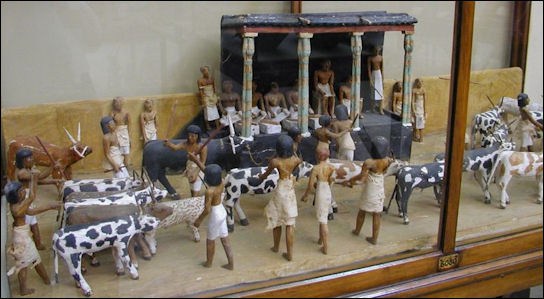

Some tombs contained "reserve heads" made from plaster casts of the mummified head which served the same purpose. The face on the sculpture had to recognizable, lest the ka get confused and inhabit the wrong statue. “Ushabti” were also included with the dead to perform the labors of the gods. These were often small exquisite small statues of ordinary people — such as potters, butchers and cooks, performing their daily chores such as rolling dough, cutting meat, kneeling at a harp and working a pottery wheel — that were brought along to perform these duties in the afterlife. Some men brought along carved stone "divine concubines" The sculptures were often incredibly lifelike. The eyes of some statues were inlaid with quartz crystal.

Block Statues in Ancient Egypt

Regine Schulz of the Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum wrote:“The term “block statue” is used in Egyptology to describe a statue type defined by its shape. It is characterized by the special squatting posture of the person represented, with the knees drawn up in front of the chest and the arms crossed above them. The body is often largely enveloped in a cloak, which intensifies the compact, cubical appearance of the statue. The block statue was one of the most common types of private sculpture in ancient Egypt from the Middle Kingdom to the Late Period, and was probably invented in the early 12th Dynasty at Saqqara. Soon thereafter, block statues came to be used all over Egypt, including the provinces. However, most of these statues were excavated at Thebes. In the so-called Karnak cachette alone, the French archaeologist George Legrain discovered more than 350, which is more than one third of all the stone statues hidden in this ancient temple-cache, aptly demonstrating the significance of the statue type in ancient Egyptian temple sculpture. [Source: Regine Schulz, Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum, Hildesheim, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

block statue

“Block statues generally represent specific private individuals who are male and adult, but never kings or deities. Very few examples depicting women appear in the Middle and New Kingdoms; rather, they are more commonly part of statue groups showing men and women together in the characteristic squatting posture Only two examples show a female, singly. One such statue may be a provincial experiment and depicts a woman with a Hathor wig. The other statue is known only from a drawing made by Richard Pococke (1704 – 1765) during his travels to Egypt in 1737 and 1738. According to Pococke’s description, the statue represents Isis; a second, separate drawing features a block statue of a male, designated by Pococke as Osiris. The statues in these two illustrations are very similar and may have belonged to a Ramesside statue group of a man and a woman that has lost its shared base.

“A special type of block statue includes uninscribed squatting figurines that are completely enveloped (draped in a cloak) and placed in Middle Kingdom model boats, depicting the pilgrimage to Abydos as part of the funeral ritual. These figurines not only represent the deceased or his statue, but sometimes also other participants in the ritual. Another special the Amun Temple of Naga (Sudan). These were possibly used for ritual purposes, but it is unclear if they represent specific individuals or just unnamed intermediaries between worshippers and gods. Three-dimensional representations of squatting people performing activities, such as the so-called servant figures, are to be distinguished from block statues. They usually do not represent specific individuals, and the gestures of their arms, their attributes, as well as their contexts clearly define the differences in their function and meaning.

“Block statues were sculpted in various hard and soft stones, and from the Late Period were occasionally carved in wood, or cast in bronze. Interestingly, in several cases where one individual was represented by a pair of block statues, a dark stone was chosen for one representation in the pair, and a light stone was chosen for the other. The size of the figure was mostly dependent on the social status of the represented person, and the functional context. The largest examples reach up to 1.5 m, but the average height ranges between 200 and 600 mm. Smaller examples were often integrated into larger structures, such as stelae or shrines (British Museum EA 569 and 570), or offering platforms (Brooklyn Museum 57.140).Miniature examples, measuring between 2 and 6 cm, served as seals, and some had an amuletic function; it is also possible that they were intended as gifts for family members or subordinates.”

Types of Ancient Egyptian Block Statues and Their Development

Regine Schulz of the Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum wrote: Block statues occur from the early 12th Dynasty to the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. The basic shape as well as possible additions varied over time. Not all examples show the represented person squatting directly on the ground. Some squat on a low rectangular element (British Museum EA 888), on a low cushion (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 03.1891), or on a low stool, which was most popular in the Ramesside Period. A back slab or pillar was used in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) and Thutmosid Period only occasionally, but from the Ramesside Period it became a standard element of most block statues (Louvre N 519). [Source: Regine Schulz, Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum, Hildesheim, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“In the early 12th Dynasty the body forms were largely visible and the only clothing worn the body, leaving only the head, hands, and usually feet uncovered. The hands of these statues are normally empty; in a few examples, the extended right hand holds a corner of the cloak (Brooklyn Museum 57.140 a, b). In the Thutmosid Period of the 18th Dynasty even the feet were enveloped (British Museum EA 48) and attributes appear in the hands. Typical for this period was the lotus flower (Louvre E 12926) although the folded linen cloth, as well as lettuce (a symbol of renewal and fertility), was also featured. A special type of block statue was developed for the high official Senenmut who served under Queen Hatshepsut. This statue type featured Senenmut and the young princess Neferura enveloped together in the same cloak (Cairo, Egyptian Museum JE 37438).

“From the 18th-Dynasty reign of Amenhotep III to the 19th Dynasty, the statue type was modified and enriched by variations of costumes, wigs, and jewelry ( Florence, Museo Archeologico 1790). Additional elements became particularly common in the Ramesside Period, such as stelae, divine figures (Art Museum of the University of Memphis, Institute of Art and Archaeology 1981.1.20: statue of Nedjem), naoi (Louvre A 110), emblems (Louvre E 17168), incised ritual scenes (e.g., Cairo, Egyptian Museum CG 567), and a variety of hand-held attributes or symbols, such as the menat or sistrum (see Paris, Louvre E 17168), as well as ankh (anx), maat (mAat), djed (Dd), and tit (tjt) signs. However, lettuce, as a symbol of renewal and fertility, became the most important of these attributes.

block statue of prophet and scribe Djedkhonsuefank

“In the Third Intermediate Period block statues of the simple, enveloped type with covered feet resurfaced in Upper Egypt. Theplain areas at the front and sides were covered with texts and incised scenes, and in some cases a large bAt-symbol-shaped sistrum appears on the front (Cairo, Egyptian Museum CG 42210). For the first time a block statue appears with a cap instead of a wig (Cairo, Egyptian Museum CG 42230). In Lower Egypt the body forms are more visible, and additions such as naoi are still common (British Museum EA 1007). The scarab on top of the head seems to be a Lower Egyptian innovation (British Museum EA 1007). In the 25th Dynasty artists drew on all possible options, and closely enveloped forms appear beside forms displaying clearly distinguishable bodies with short kilts. The surfaces of the bodies are less tightly decorated than in the earlier Third Intermediate Period, and the sides of the statues are often plain. In the Late Period this trend continues, but the diversity of forms further expands (Cairo, Egyptian Museum CG 48624; Metropolitan Museum 1982.318; Los Angeles County Museum of Art 48.24.8). Graywacke became a very popular material, and the high polish of the surface, as well as the fine carving of the inscriptions, is characteristic for this period. “In the course of the late 26th and 27th Dynasties block statues became less common but, particularly in Upper Egypt, were revived in the 30th Dynasty, extending into the early to mid-Ptolemaic Period. During this time the enveloped subtypes became more common (Brooklyn Museum 69.115.1). A last innovation came with the introduction of magical texts covering the entire statue, including the head, and the occasional addition of Horus-stelae (Cairo, Egyptian Museum JE 46341).

“In addition to single examples, groups of two or more block statues exist, which sometimes also combine block statues with other statue types. Furthermore, smaller representations of one or more family members sometimes appear in the front or on the sides of the squatting statue (Brooklyn Museum 39.602; Cairo, Egyptian Museum JE 46307) as well as representations of deities and divine symbols. Several officials had more than one block statue, and pairs are common; such pairs occur in funerary contexts during the Middle Kingdom, whereas from the New Kingdom to the Late Period they are limited to temples. A few celebrities even had multiple block statues. Ray, the High Priest of Amun under Ramesses II, had four block statues in Karnak—two in the temple of Amun and two in the temple of Mut. The largest number, however, belonged to Senenmut, a high official under Queen Hatshepsut, who had at least eight, six of which were placed in the temple of Amun at Karnak.”

Function and Meaning of Ancient Egyptian Block Statues

Regine Schulz of the Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum wrote: Most block statues were positioned in ritual places, particularly the precincts and forecourts of temples. From the New Kingdom onward they occasionally functioned as doorkeepers or as intermediaries between worshipers and deities. Smaller examples were combined with other monuments, such as stelae (British Museum EA 569 and 570), or mounted on pedestals. Only very few examples of the Middle and New Kingdoms come from funerary contexts, where they were placed in niches or small, separate chambers in the front or outer parts of the tomb. These statues were not the focus of the ritual for the deceased tomb owner, but rather were associated with the rituals for deified kings (in the Middle Kingdom) or with deities particularly venerated in the cemetery (in the 18th Dynasty). [Source: Regine Schulz, Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum, Hildesheim, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The meaning of the block statue type has been intensively discussed in Egyptology, and a wide variety of interpretations have been proposed. “The form of the statue has been variously interpreted as a posture of calmness, a typical “everyday life” depiction of an Oriental squatting posture, a manifestation of renewal and re-creation, as well as of protection, and as an abstract aesthetic concept. The creation of the block statue type in the early Middle Kingdom was indeed function- and meaning- related. The original meaning derives from two iconic elements: the special squattingposture, and the crossed arms. In ancient Egypt, squatting was the conventional working or resting posture. However, in the statuary of private individuals it expressed the privilege of being part of the ritual community.

“Nonetheless, the squatting individual was neither the main focus of the ritual nor the active ritualist. He was entitled to be present for, and to participate in, the rituals for deities and deified kings in temples and along processional routes, including those in the cemetery. The crossed arms amplify this meaning and convey a respectful, yet passive, submissiveness toward a god, king, or superior. During the consolidation phase of the block statue type in the mid-12th Dynasty, an enveloping cloak that covered most of the body was added. Such cloaks were also used for other statue types and conveyed the higher rank of the represented official, as well as his right to participate in temple rituals and processions. The crossed arms and the enveloping aspect also signify an Osirian dimension and represent the desire for renewal. Another hint of the block statues’ meaning can be found in the term Hzyw, “the praised and honored one,” which describes an individual of high ethical standards, excellent achievements, and piety. The Hzyw-status implies not only recognition, but also participation in the rituals and partaking in the offerings, as well as a promise of renewal after death. From the 22nd Dynasty the term Hzyw was occasionally written with a block statue as a determinative, and used to describe the honored person, as well as his statue. Some very rare depictions of block statues on stelae of the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.) may also refer to the Hzyw-status.”

Ancient Egyptian Wooden Sculptures

The Egyptians produced some wonderful wooden sculptures and lots of poorly crafted ones. Many of them were portraits, family scenes, depictions of everyday life and group scenes of individuals working in fields or boats. Describing a wooden statue of a hunting leopard, Blake Gopnik wrote in the Washington Post: “The coiled muscles in the feline’s shoulders have a prowling tomcat’s hunch; its head is down and to one side, as though its bobbing for a scent.”

wooden sculpture

Julia Harvey of the University of Groningen wrote: “Wood was a widely used material for sculpture in ancient Egypt from the earliest times. It was mostly native timber, but from the New Kingdom onwards, sculptors also used imported wood species. The majority of extant examples are from funerary contexts, found in both private and royal tombs, although the art of fine wood carving was also employed for furniture and other ritual objects. [Source: Julia Harvey, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Wooden sculpture has appeared alongside stone sculpture throughout Egyptian history, from prehistory down to Ptolemaic and Roman times. Although the vulnerability of wood to moisture and other threats, including termites—something the ancient Egyptians were clearly aware of—has often obscured this fact, fortunately enough survives to allow us to state for certain that wooden sculpture was always an important aspect of funerary and ritual practices. Wooden sculpture in this context has been taken to mean wooden statues of the king and queen and those of the tomb owner and his or her family. This means that certain categories with perhaps a claim to the designation sculpture have been excluded. These include cosmetic implements (e.g., mirror handles, unguent pots, cosmetic spoons, etc.), statues of prisoners, tomb models (with the exception of the extraordinarily elaborate female offering bearers from the early Middle Kingdom), harp finials, shabtis, statues of gods, and other ritual objects.

Wooden sculpture throughout Pharaonic history was mainly made of native timber— acacia, sycamore, and tamarisk, and sometimes a combination of these. For example, a statue of acacia may have a base made of tamarisk. The fibrous and knotty character of the native woods meant that statues larger than 300 - 400 mm had to be made from several separate pieces joined by dowels and mortise and tenon joints. The joints were subsequently concealed by a layer of paint or painted plaster on which the details of costume and jewelry were added. It is unfortunate that it is this painted layer that has often suffered the most damage. Imported woods like ebony and cedar were also occasionally used. In the New Kingdom, imported woods were favored for the production of royal statues in wood, and proportionally more private statuary was made of ebony. We should bear in mind, however, that as yet relatively few statues have had their wood scientifically analyzed, so all conclusions are tentative.

“Ancient Egyptian artisans were highly skilled at carving wood, and illustrations of workshop scenes often include statue-making. Although the inscriptions accompanying these scenes rarely refer to the statues depicted, the tools shown are a good indication of the material in question; an adze in the hand of a workman is an indication that the material is wood, whereas hammers and mallets tend to be limited to working stone. An adze, of course, would be quickly blunted if used on stone, and a mallet would be far too crude an instrument to work wood. The statues are usually shown in a completed state, regardless of the type of tool action. What is also revealed is that the artisans worked as a team rather than as individual artists; many individuals were involved in the production of a single statue.

“Unfortunately, not enough wooden statues survive to establish whether there were local fashions centered around a particular town or necropolis. We can surmise a major Old Kingdom workshop in or around Memphis producing for the necropolis of Saqqara, and in the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom there were centers at Assiut, Meir, and Beni Hassan. Few conclusions can be drawn from this, however, beyond remarking that the wooden statues from Beni Hassan tend to have extremely large, painted eyes. During the New Kingdom and later, the main workshops were in Thebes and Memphis, and it will come as no surprise that most provenanced statues from these periods come from these two locations.”

Wooden Statues in the Old and Middle Kingdoms: Wigs and Daily Life

Calving cow Julia Harvey of the University of Groningen wrote: “Wooden statues in the Old Kingdom may have been considered necessary to depict the tomb owner in his more active roles, accompanied by his wife. Stone statues in the tomb are usually static groups or seated statues, whereas those of wood usually show the tomb owner striding with staff and scepter in his left and right hand, respectively. These two aspects, active and passive, are matched by the depictions on Old Kingdom tomb walls. The statues, both wood and stone, first appear in the superstructure of the tombs, then in specially designed serdabs, and towards the end of the period in the burial chambers as well. As we move on in time, the quantity of wooden statues in each tomb increases while the size and quality decrease. In all, over 250 statues survive from this period. No royal statues have survived from the Old Kingdom. [Source: Julia Harvey, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Male statues in the Old Kingdom show a wide variety of costume and wig types, but unfortunately no combination of these can be linked to a specific role or title. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that the plaster layer with the subtle details of decoration has usually not survived the test of time. Female statues are nearly always standing or with the left foot just slightly advanced. Inscriptions on the bases of statues of both sexes are invariably lists of titles and names. The well- known offering formula “for the ka of” does not appear until the very end of the period, but it becomes standard during the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom. This is why the usual name chosen by Egyptologists for tomb statues in both wood and stone is “ka statues”.

“During the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom, the emphasis shifts from the tomb owner and his wife alone to include models of daily life as well. Particularly fine examples of female offering bearers are known from the tomb of Meketra, for example. These female offering bearers are probably personifications of funerary estates, three-dimensional examples of the friezes of personified estates decorating the lower parts of many temples. As the period progresses, the quality of the figures and models in general once again declines, although there are still a few exceptional pieces. The average size of wooden statues decreases after the 11th Dynasty, and although the range of costumes and wigs on male statues is much wider, there is still no prospect of identifying individual costumes and wigs with particular offices. One notable exception is the statue of Yuya in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which depicts him wearing the vizier’s costume. “Tombs and even simple graves in the provincial cemeteries, for example, at Beni Hassan, now often contain wooden statues of the tomb owner, resulting in a corpus of about 500 statues in total. Female statues resemble those from the Old Kingdom, with the addition of new wig types. Perhaps the most notable difference is that the females now have very pronounced waists and hips. The earliest extant royal statues in wood date to the 12th Dynasty (for example, the statues of Senusret I in Cairo and New York). Wooden shabtis are also known from the Middle Kingdom, but the best examples date to the New Kingdom.”

Wooden Statues in the New Kingdom and Afterwards; More Royals and Gods

Julia Harvey of the University of Groningen wrote: “A preliminary survey has revealed that the wooden statues from the first part of the 18th Dynasty continued to be inspired by the Middle Kingdom and are full of force and character. Model scenes disappear as do the female offering bearers. The New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) types appear to duplicate those from the same period in stone to a greater extent than in the earlier periods, and it is at last sometimes possible to link costumes to particular functions. The elaborate clothing of the later 18th Dynasty, for example, with its many pleats and folds was duplicated not only on the plaster coating but also in the wood itself, thus enabling us to identify military officers, priests, and priestesses with a much greater degree of certainty than before, even when the base of a statue is missing. When the base is extant, the names and titles of the deceased as well as an offering formula are now often accompanied by a dedicatory text. The dedicators are usually the son or daughter of the deceased, but often the parents, a brother, or sister appear, perhaps indicating that the deceased had died young. [Source: Julia Harvey, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

scribe statue

“The preliminary total for New Kingdom statues is about 80 male and 80 female, with over three quarters of that total dating to the period from Amenhotep III through the 19th Dynasty. Two interesting subgroups of statues come from the Deir el- Medina necropolis. One subgroup comprises statues of the tomb owners holding a standard crowned by a sacred emblem, often a hawk’s head or a ram’s head; the other subgroup consists of statues of the deified Ahmose- Nefertari, the wife of Amenhotep I. An interesting extra detail concerning the subgroup of standard bearers is a carved relief of either the wife or son on the left-hand side. Pair statues are extremely uncommon in all periods; for example, only three are known from after the second half of the 18th Dynasty.

“Royal sculpture in wood is much more common in the New Kingdom, and many royal tombs and temples of the period were provided with resin-coated or gilded wooden statues. The larger, life-size ones are usually freestanding statues of the king (e.g., the statues from the tombs of Thutmose III, Tutankhamen, and Horemheb), whereas the smaller ones are ritual statues usually placed in wooden shrines. The latter show the king striding while wearing the white or red crown, harpooning in a papyrus skiff, or standing on the back of a panther. Statues of queens are much less numerous and seem also to be on a much smaller scale. However, they are no less magnificent when they do survive, for example, the wooden head of Queen Tiy, which was recently reunited with its headdress. A pair of statues of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy, found at Kom Medinet Ghurab in the Fayum and now in the Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim, also deserve mention—despite their tiny size (60 and 60.5 mm, respectively), the detail is exceptional. Votive statues of the deified Ahmose-Nefertari became popular during the Ramesside Period (see above).

“During the later Egyptian periods, private wooden statuary becomes much less common, although this could be an accident of preservation. A total of only four statues in wood of male and female tomb owners are currently known from the Third Intermediate Period, 25 from the Late Period, and only three from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. Those from the Late Period, like most art of that time, imitate Middle Kingdom styles. Also during this period, kneeling figures of Isis and Nephthys begin to be placed on either side of the sarcophagus in the burial chambers of private tombs; ba-birds, falcons, and akhom figures (archaic figure of a perched falcon), as well as Anubis jackals were placed on top. Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figures, often with a cavity containing a papyrus roll, were also popular.”

Shabtis

Tutanhkamun (King Tut) shabti

Figurines called shabti were often buried with the deceased. Their purpose was to do the deceased's work in the afterlife for them. Shabtis were small burial figurines that served like magical servants, doing chores for the deceased in the afterlife. Rich people often had had many shabties. According to an Brooklyn Museum catalog on ancient Egyptian grave goods the wealthy might have a different shabty for every day of the year, “40 shabties were an ideal number to own in the Ramesside Period” because that provided “enough workers for each of the 30 days of the month plus overseers and foremen." [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, March 11, 2010]

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: “During and after the annual flood of the Nile, the population were subject to compulsory labour on state projects such as building and maintenance of the irrigation system. In life it would be possible to avoid this by providing a substitute; in death, mummiform figurines or "Answerers" could serve the same purpose. The Egyptian words for these statuettes (usually called shabtis in English), are ushabti and shawabti. These words are of uncertain origin but may have been derived from the Egyptian word wSb(1) meaning "answer." [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

“The backs of these figurines were inscribed with Chapter 6 of "The Book of the Dead." This spell ensured that if the owner of the shabti was called upon at any time to do any kind of compulsory labour the shabti would respond and perform the duty instead of its owner. The practice of including these figurines in burials started during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2040-1640 B.C.(2)) when only one was usually included in the burial. The practice continued and by the Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1070-712 B.C.)there were sometimes so many in a burial that the shabtis were put in a special box: the custom had become to have one shabti for every day of the year with 36 overseer shabtis. The practice of including these figurines in burials died out in the Ptolemaic Period (332 B.C.-395 AD).

See Separate Article: SHABTIS: TYPES, PURPOSE, SPELLS, CRAFTSMANSHIP africame.factsanddetails.com

Female Figurines in Ancient Egypt

Elizabeth Waraksa of UCLA wrote: “Figurines of nude females are known from most periods of Pharaonic Egyptian history and occur in a variety of contexts.” They are typically “small, portable representations of nude females averaging approximately 15 centimeters in height and occurring in clay (both fired and unfired), faience, ivory, stone, and wood. Such figurines are best represented from the Middle Kingdom onwards. Long regarded as toys, dolls, or concubine figures, female figurines have commonly been referred to as votive “fertility figurines.” However, recent research suggests a broader and more active function for these figures, including evidence for their deliberate destruction, in a variety of healing and apotropaic rites. [Source: Elizabeth Waraksa, University of California, Los Angeles, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Although most female figurines take the form of a nude woman, clothing is indicated on a few examples. Particularly emphasized on female figurines are the hair, breasts, and pubic area. Some female figures hold or suckle a child, or have a child next to them on a bed. Female figurines often lack proper feet and were not intended to stand upright, although some female-on-a-bed figures could be supported by the legs of the bed. Some rare female figures are fashioned in a seated or kneeling position.

“Depending on the material of which they were made, female figures were either carved or modeled by hand, or molded in an open mold; many were painted or embellished. Clay figurines could be modeled or molded of Nile silt, marl clay, or local oasis clay, and were frequently painted. Many New Kingdom through Late Period ceramic figurines were coated with a red wash post-firing. More elaborate ceramic and stone figures, in particular those depicting a female on a bed, were painted in polychrome, especially during Dynasties 18 - 20. A particular type of Third Intermediate Period ceramic figurine was painted with polychrome stripes.

“Some marl-clay figures of the Middle through New kingdoms were embellished with faience or metal jewelry; fringed, colored linen; and “beaded” hair—that is, hair represented by beads of mud, faience, or shell strung on linen thread. “Faience female figurines, including woman- on-a-bed examples, were molded and feature darker coloration to emphasize the eyes, nipples, navel, and hair, as well as to indicate jewelry, tattooing, and, on some examples, patterned clothing. Holes in the heads of some faience figurines reveal that hair, either real or artificial, was probably attached.

“Ivory figurines, which are rare, were carved and polished. Stone figurines were carved and sometimes painted either in polychrome or with a single pigment such as black (to emphasize hair and jewelry), or red or yellow (to emphasize flesh areas). Wooden female figurines, including the group known as “paddle dolls,” were carved and painted in black or polychrome to indicate jewelry, fabric, and pubic hair. Some examples bear painted images of birds, crocodiles, scarabs, and the goddess Taweret.

“Female figurines have been found in the full range of excavated sites in Egypt, from houses, temples, and tombs in the Nile Valley to cemeteries in the western oases, mining sites in the Eastern Desert and Sinai Peninsula, and Nubian forts. Often, female figurines derive from refuse zones in proximity to these areas. Most female figurines adhere to standardized types within chronological periods. This uniformity, together with their decoration in a variety of media, suggests mass production at a state-supplied workshop. Temple workshops are the most likely locale for their production, and male craftsmen, their most likely manufacturers.

One significant aspect of female figurines dating to the Middle Kingdom and later is their pattern of breakage. Although some female figurines are found whole, many display a clean, horizontal break through the torso-hip region—usually the most robust part of the figure —and are therefore recovered as either the upper or lower half only, or in joining fragments. Such breakage is indicative of deliberate destruction, which most likely occurred at the conclusion of a rite before the figurine was discarded. In combination with the frequent occurrence of the figurines in refuse zones, this breakage highlights their temporary utility.

Purpose of Ancient Egyptian Female Figurines

Elizabeth Waraksa of UCLA wrote: “Despite their being a well-known class of object, the exact function(s) of female figurines of Pharaonic Egypt has remained elusive. They have been variously categorized as “toys,” “dolls,” “wife figures,” “concubines (du mort),” or “Beischläferin.” Many of these terms were employed on the erroneous assumption that the figurines served as male tomb owners’ magical sexual partners in the next life, but it is now clear that female figurines could be placed in the tombs of men, women, and children, as well as deposited in domestic and temple areas, and the concubine theory has largely been abandoned. The prevailing theory on the function of female figures is the votive “fertility figurine” thesis suggested by Pinch. The iconography of the figures, as well as their discovery in temples to Hathor and domestic shrines, favors such an interpretation, as do inscribed female figures asking for the birth of a child (see Terms and Textual Evidence above). Recently, this thesis has been expanded to situate female figurines in a broader range of magico-medical rites not exclusively related to women and fertility . Magical spells calling for female figures of clay and wood reveal that such objects were ritually manipulated in rites to repel venomous creatures and heal stomachaches (see Terms and Textual Evidence above). These spells, together with the excavation of female figurines as part of a magician’s kit, suggest that the owners and users of female figurines were literate priests/magicians. Female figurines are thus best understood as ritual objects applicable to a range of magico-medical situations and that were frequently broken and discarded at the conclusion of their effective lives. [Source: Elizabeth Waraksa, University of California, Los Angeles, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian terms for magical figures are difficult to isolate. Nevertheless, several terms for clay female figurines have recently been identified. A spell to repel venomous snakes calls for a sjn , which can be translated “clay figure (of Isis).” A spell to relieve a stomachache calls for the words to be spoken over a rpyt nt sjnt, a “female figure of clay,” and for the pain to be transferred into this rpyt Ast or “female figure of Isis.” The term rpyt may be understood as a generic one applied to female images of all sizes and materials, including magical figurines . There can be little doubt that many other spells calling for female figurines existed but are now lost to us. Inscribed female figurines are very rare; only three examples are known, each bearing an appeal for a child. The wording of the appeals is indicative of a funerary context (in one case, the hetep di nesut formula is used), suggesting a supplicatory role for inscribed female figurines in a tomb setting.

“The context, textual evidence, and iconography of female figurines relate them to a host of female deities. Archaeological evidence suggests a connection to the goddesses Hathor and Mut. The iconography of painted wooden figurines suggests an association with Nut and Taweret. Magical spells explicitly link female figurines to Isis and Selqet. It is likely that female figurines were fashioned as generic females so that they could serve as any one of numerous goddesses, depending on the situation at hand. The figurines possibly also were fashioned in this generic form in order to protect the deity invoked from the affliction she was being asked to address. It was through the recitation of a spell that a female figurine actively became a goddess for the temporary purposes of healing and protection.”

Reserve Heads of Old Kingdom Ancient Egypt

Barbara Mendoza wrote: The enigmatic reserve heads of the Old Kingdom (2670-2168 B.C.) in Egypt have been the topic of much discussion and debate since their discovery, primarily on the Giza Plateau, at the turn of the twentieth century. Their purpose and meaning to the ancient Egyptians confounded the first excavators who discovered them (de Morgan, Borchardt, Reisner, and Junker), and have puzzled the later Egyptian art historians, archaeologists, and Egyptologists who have studied them over the past century. This is mainly because the Egyptians did not leave a record for their use or function and because the heads were discovered in secondary context. All of the tombs in which they were found were either plundered or disturbed by flood, leaving them to much speculation. Their original discoverers and subsequent scholars have advanced numerous theories, which may or may not have a basis in the archaeological record. [Source: Barbara Mendoza, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2017]

Approximately life-size, reserve heads were made as self-contained heads, cut off at the neck; they are somewhat portrait-like, and most of them appear with close-cropped hair . Both sexes are represented among the 33 extant examples; and although their faces appear idealized, some of them possess individualized features. Most were made of limestone, and a few had traces of paint and/or plaster. Some heads show evidence of intentional damage. When stood on end, the heads appear to gaze upward — although it is not known whether they were meant to stand on end. Most of these figures were manufactured during the 4th Dynasty and were found primarily in a burial or funerary context.

The term “reserve head,” first advanced by Borchardt (1907) and later subscribed to by Junker and Reisner derived from his theory that these sculpted, portrait-like heads were placed in the burial shaft or chamber as a “substitute for the head of the deceased,” that is, held in reserve should the head of the deceased be destroyed Thus, the heads were defined by their supposed function.

Several theories have developed about the function and meaning of the reserve heads. Reisner, considering the physical properties of the heads, hypothesized that since they were cut off at the neck, they could be stood upright — given the flat, smooth surface of the base. He thought that they may have stood on a sarcophagus or “on the floor of the chamber” because they were originally placed in the burial chamber. Furthermore, he believed that the heads were substitutions for the vulnerable heads of the deceased, as did Junker (though he considered a different use) and Borchardt, and he first advanced the theory that the ancient Egyptian concept of “substitution” extended to the function of the “reserve” heads, hence their name.

The concept of substitution is simple. By Dynasty 3, the ancient Egyptians believed that the king had a kaor “double,” which was created when he was born, stayed with him throughout life, and “lived in the tomb” upon death. Provisions were made for thekain the burial process; that is, a funerary temple or serdab (statue chamber) was built inside the tomb for the kaand a statue was created for it to live in. The statues were representations of either tomb owners alone or the tomb owner with the royal family and served “as substitute bodies for the dead”. With the statue as home for the ka, it could come and go at will and partake in food offerings, which were offered periodically by mortuary priests. Mortuary priests maintained the provisions of the deceased. The funerary temple was often situated over a passage that led down to the burial chamber.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Reserve Head by Barbara Mendoza escholarship.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024