Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “Almost all categories of instruments were represented in Mesopotamia and Egypt, from clappers and scrapers to rattles, sistra, flutes, clarinets, oboes, trumpets, harps, lyres, lutes, etc. ...In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), Egypt borrowed several instruments from Mesopotamia: the angular vertical harp, square drum, etc. The organ, invented in Ptolemaic Egypt, is first attested in its new, non-hydraulic form in the third century a.d. Hama mosaic.[Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“Names of musical instruments are fairly well known owing to the hieroglyphic inscriptions accompanying the paintings, but they are rather vague : for instance the word mat designates the flute as well as the clarinet. No document has yielded any indication about the music, either theoretical or practical. Ancient music may have survived to some extent in that of the tribes of the Upper Nile or in oases such as that of Siwa. This might be suggested by some satirical songs dealing with animals, in the line of fables and scenes depicted on papyri and ostraca. They have been recorded by Hans Hickmann, a more positive contribution than the hypotheses he has put forward in numerous publications about the so-called chironomy and the play of musical instruments. Sachs’ early polyphonic theory, based on pictures of harpists, is without foundation, for it cannot be proved that both hands of the harpist struck any two strings simultaneously, while his further theory of the pentatonic basis of ancient oriental music has been disproved by the discovery of the heptatonic system in ancient Mesopotamia. ^*^

“The instruments may be classified following normal practice proceeding from the simplest to the most complex, into idiophones (clappers and the like), membranophones (drums), aerophones (flutes and reed instruments) and chordophones (string instruments). ^*^

“Organs . It was in third-century B.C. Egypt that Ctesibius, a Greek of Alexandria invented an instrument combining the pan-pipe with a key-board. The air came from a tank in which its pressure was kept constant by a volume of water: hence the name hydraulos , meaning literally water-oboe, a name which was retained even after the water tank was superseded by another device, the pneumatic bellows. The change must have taken place before the third century A.D., for the new contraption is depicted yet again on the Hama mosaic. The hydraulos served purely profane purposes: it was used in circus games and musical competitions. Only in the Middle Ages was it intro- duced into the liturgy of the church, under the name of organon or organum , meaning literally ‘instrument’ .” ^*^

See Separate Article: MUSIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

““Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt” by Lise Manniche (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Music of the Most Ancient Nations - Particularly of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Hebrews” by Carl Engel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Musical Aspects of The Ancient Egyptian Vocalic Language” by Moustafa Gadalla (2016) Amazon.com;

“Love Poetry and Songs from the Ancient Egyptians” by Gilbert Moore (2015)

Amazon.com;

“Echoes of Egyptian Voices: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Poetry” translated by John Foster (1992) Amazon.com;

The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry” by William Kelley Simpson, Robert K. Ritner, et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“Writings from Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkerson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple” by David Klotz | (2006) Amazon.com;

Hymns, Prayers and Songs: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Lyric Poetry”

by Susan Tower Hollis and John L Foster (1996) Amazon.com;

“Meditation Music of Ancient Egypt” by Gerald Jay Markoe (CD) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Dances” by Irena Lexová (1999) Amazon.com;

Clappers, Scrapers and Rattles from Ancient Egypt

It seems likely that idiophones such as clappers and rattles were among the first musical instruments. It has been theorized that they grew out of man's natural desire to dance and make rhythm, and succeeded human actions such of stamping the ground and clapping hands. Idiophones appear with some frequency in ancient Egyptian iconography, appearing to augment cadence led by the hands or feet, which are believed to have played a dominant part in the music and the dance of ancient Egypt.

Sibylle Emerit of the Institut français d'archéologie orientale wrote: “The first percussion instrument known in the Nile Valley was the clapper. It has been attested since prehistoric times, in the iconography as well as in archaeological remains. Made of two wooden or ivory sticks, either straight or curved, they are struck against one another by the musician with one or both hands; the presence of a hole made it possible to tie them together. Various ornamental motives decorate these instruments, varying according to the period they were in use: Hathor, either human or animal headed, a hand, a humble papyrus, or a lotus flower. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

clappers

“Sistra and the menit-necklace were also used as percussion instruments. This use has been attested from the Old Kingdom to the Roman Period. Two types of sistra coexisted, the sistrum in the form of a “naos” and the arched sistrum. In both cases, it is a kind of rattle formed with a handle and a frame crossed by mobile rods, sometimes embellished with metal discs. The swishing sound made by the menit-necklace was caused by rows of beads, shaken by the musician, which would be the counterweight part of the collar.

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “The simplest percussion sticks are held one in each hand. In Egypt, clappers imitated a forearm, in bone or ivory, ending in a sculptured hand In the second type, found only in Egypt, both clappers are held in one hand, beingattached together at their base and terminating in a small human or animal head. Theyare depicted in one tomb of the Middle Kingdom and in some of the New Kingdom. A third simpler type is made of a piece of flexible wood slit down the middle, except for a short section at the base, serving as a handle. Such instruments continued in use until the Late Period (712–332 B.C.), but by that time they were reduced to about 80 mm. in length and made in wood, often in the shape of little boots, fir-cones, or pomegranates. These were in time to develop into the castanets of Andalucia but already are to be found in Syria, on the third-century Hama mosaic. A fourth type has each clapper terminating in a small metal cymbal fixed to it with a nail. It is found in the first centuries a.d., not only in Egypt but once more on the Hama mosaic, in North Africa at Carthage on mosaics, and on Roman sarcophagi. Its origin is unknown; the type appears in Iran on Sasanian silverware and survives in Byzantium and in medieval manuscripts. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“Rattles exist in two categories : gourd and ‘pie-crust’ rattles, filled with pebbles or other small, hard objects, made of clay, sometimes in animal shapes, and found both in Mesopotamia and Egypt..Bunch rattles are depicted in Egypt in scenes of the Middle and New Kingdoms and called mainit or menat. This instrument is made of several rows of beads held together and attached by two chains to a long metal handle. Sachs did not recognize them as musical instruments, but one may cite a text in which the return of an important person is celebrated by the sound of the mainit and sistra. A scene in a Theban tomb shows women brandishing a mainit in one hand and a sistrum in the other. More- over, one menat in the Louvre has its metal pieces slightly worn off owing to their frequent concussion. ^*^

“The sistrum consisted of a handle and a frame with jingling cross-bars. In Egypt the spur-sistrum is already present on a relief of the sixth dynasty now in Vienna. Later bronze sistra are in the British Museum, in the Louvre and in other collections. Another form, exclusively Egyptian, is in the shape of a small temple or naos , the walls of which have holes, with jingling cross-wires strung through them. The handle is variously adorned, very often with the head of the goddess Hathor in whose honour the instrument was played, before it was taken over by the Isis cult. The naos- sistrum is attested at sixth-dynasty Dendera. A good picture of it is found at Beni Hassan in a tomb of the twelfth dynasty. It may be in bronze, silver, or ivory; some, votive ones, are in enamelled porcelain. The third type, dating from the New Kingdom, had a horseshoe-shaped frame instead of the naos. Several wires slipped back and forth in the loose holes and could have jingling discs strung upon them to increase the noise. This type of sistrum spread with the Isis cult all over the Roman empire. ^*^

Drums, Cymbals and Bells in Ancient Egypt

Round and square kettledrums and the castanets, which were the instruments usually played by the dancers. Barrel-shaped drum and the trumpets were played by soldiers. Sibylle Emerit wrote: “The two main membranophones used by ancient Egyptians were the single membrane drum mounted on a frame and the barrel-shaped drum with two membranes. The single membrane drum is attested in the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.) in a scene carved in the solar temple of Niuserra in Abu Ghurab. It is a very large-sized round drum, which was used during the Sed Festival. In the New Kingdom, a small-sized model, the round tambourine, was depicted to be exclusively played by women in a context of ovations. A so-called “rectangular” tambourine was also used by the musicians, but only during the 18th Dynasty. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The barrel-shaped drum has been attested from the Middle Kingdom onwards. The instrument, suspended round the neck of the musician, was struck with the hands. The use of drumsticks seems to have been unknown in Egypt. In the New Kingdom, this instrument was only played by men and more particularly by Nubians during military or religious processions. In the Late Period, depictions are found of a small-sized barrel-shaped drum in the hands of some women . The existence of a vase- shaped drum is still debated.”

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “In Egypt, drums are relatively rare. There is none attested in the Old Kingdom. One specimen from the twelfth dynasty was found in Tomb 183 at Beni Hassan. It is cylindrical, 1 m. high with two hides held by strings. Only in the New Kingdom did drums become common, though never introduced into the Osiris cult. They are depicted in military or private scenes. They are barrel-shaped with two hides, and often suspended from the neck of the musician by means of a leather thong. The fact that the hides are held and tightened by means of strings or laces may point to a Nubian provenance, for this is the common type of drum in present-day Africa, whereas the Mesopotamian ones are glued or nailed. Another drum made in terracotta is the ancestor of the Arabic darbukka ; the type appears on a Theban relief. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“A frame drum in a scene of the twelfth dynasty is about 750 mm. in diameter and resembles the contemporaneous Hittite instrument. More remarkable is the rectangular drum with concave sides, about 700 mm. long, of the eighteenth dynasty. Both this and the round terracotta drum have their origin in Asia. Neither in Mesopotamia nor in Egypt were drums, even the largest ones, ever played with a stick. This accessory, probably of Indian origin, does not appear until the Roman period in the A.D. third century. ^*^

“Cymbals, bells, and crotals (small metal rattles) were introduced more recently in Egypt, probably during the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). “In Egypt, large cymbals, 150 mm. in diameter, were probably held and struck like present-day examples. They are, however, only depicted on terracottas of the Greek period. But one pair, is supposed to date back to 850 B.C. Another, on a Syrian bronze, from about 1200 B.C. is in the Musee du Cinquantenaire. The Greek name for it was adopted in the ancient world and no Coptic name existed. Many bells in silver or gold or bronze were in use in the Late Period in Egypt and the Near East.” ^*^

Flutes in Ancient Egypt

flutes and pipes

The flute was the only wind instrument in use. There were two forms of flute under the Old Kingdom; the long flute, the player held obliquely behind him, and the short flute almost suppressed in favor of double flutes, as such as that played by the musician in the accompanying plate. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “The oldest representation of a wind instrument is depicted on a mudstone palette of the Predynastic time [fourth-millennium B.C.]: it is the long flute. Cut in a reed with a large diameter, it possessed only a small number of holes in its lower part. In the Old Kingdom, this flute occupied a dominating place in music scenes in the private funerary chapels. Only men used it during this period. In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), the fashion of this instrument started to fade. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: The flute on the pre-dynastic palette “is played by an animal. Sachs sees here a hunter disguised as an animal to lure game. This interpretation is, however, far from convincing; it might as well be a satirical fable like those the Egyptians were fond of in later times as in the Turin papyrus. The long flute is also depicted on reliefs of the Old Kingdom as part of orchestras. It is about 1 m. long and is held obliquely, from which may be inferred that there was no proper mouth- piece. The finger-holes, four in number, are pierced in the lower part of the pipe. A shorter flute is shown being played almost horizontally, straight in front of the musician, which means it was either a duct flute or an oboe. Finally the cross or trans- verse flute appears in the Ptolemaic period. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

Horns in Ancient Egypt

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “In Egypt the horn is never depicted. Some specimens in terracotta have been found. They were probably reserved for signalling. Best-known is the pair, one in silver and one of bronze found in the tomb of Tut-ankh-amen. But it also served for military purposes, as pictured for the first time about 1515 B.C. Its invention was attri- buted to Osiris, in whose cult it was used. Plutarch remarked that its blare was like an ass’s bray. Short trumpets in gold or silver also occurred in prehistoric Iran at Asterbad and Tepe Hissar. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010]

Emerit wrote: “The trumpet was used in Egypt since the New Kingdom, mainly in a military context. This instrument did not look like the piston trumpet invented in the nineteenth century, which is capable of giving all the notes of the scale. The Egyptian trumpet, straight and short, produced only the harmonic series of a note. It served especially for passing on orders instrumentalist Dd-m-šnb: “The one who speaks on the trumpet.” In the tomb of Tutankhamen, two trumpets were discovered, one made of silver and the other one of copper. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, new instruments were introduced to enrich the instrumentarium with, on the one hand, the introduction of the panpipes by the Greeks and, on the other hand, the invention of the hydraulic organ in Alexandria during the third century B.C.. Terracotta figurines show musicians playing these instruments.” A Hittite relief in the Louvre shows a pan-pipe instrument with six equal pipes which must have been stopped at different levels in order to produce different pitches. The instrument, common in Greece, was introduced from there into Egypt in the Graeco-Roman period. ^*^

Reed Instruments in Ancient Egypt

double flute player

On clarinet-like instruments, Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “Missing in Mesopotamia, the pipe with a single vibrating tongue was very popular in pairs as early as the Old Kingdom in Egypt, where it appears to have been, indigenous. Its earliest occurrence is on a relief of 2700 B.C. in the Cairo Museum. The twin pipes are coupled and their holes correspond. The instrument survives in modern Egypt under the Arabic name of zummara. The player stops the corresponding holes of both tubes simultaneously with one finger and as the holes, roughly cut into an uneven cane, produce slightly different pitches, the effect is a pulsating sound. Oboes seem to “have been introduced from Asia in the New Kingdom. The sound is produced in the double mouth-piece by the vibration of two reeds. The instrument was used in pairs, could be of considerable length and was played chiefly by women. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “In Egypt, one can distinguish the long flute, the double clarinet, and the simple or double oboe, but it is, however, very difficult to differentiate with certainty these four instruments, which are individualized— from an organological point of view—by the presence or the absence of a simple or double reed. When the instruments survived, these tiny reeds have generally disappeared, and they are never visible in the iconography. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The double clarinet has been attested since the 5th Dynasty. During the Old Kingdom, it was the most frequently represented aerophone. It is a simple reed instrument with two parallel pipes tied together by string. The musician plays the same tune on both pipes, but since the holes’ spacing is not strictly parallel, the obtained note is slightly dissonant.

“The oboe appeared during the New Kingdom. It consisted of one or two long, thin pipes, which separate starting from the mouth of the musician to form an acute angle. The melody is only played on one of the pipes, the other one giving a held note. This instrument, mainly played by women during that period, supplanted the long flute and the double clarinet. According to the pictorial record, the latter two instruments did not disappear from the musical landscape and were played until the Roman time. With the arrival of the Ptolemies, a new type of oboe was attested in Egypt: the Greek aulos.”

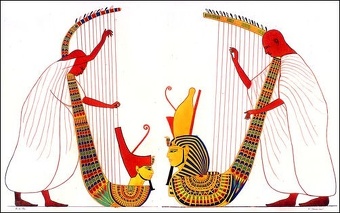

Harps in Ancient Egypt

The harp it seems was the favorite instrument in ancient Egypt. They came in two sizes. The medium size had six or seven strings, while the larger one had often twenty strings, For the former the performer was seated, for the latter he was obliged to stand. A very small harp, played resting on the shoulder, appears only in the time of the New Kingdom. " The construction of the harp does not always seem to have been the same, for instance, the resonance chamber at the lower end of the instrument is found only during a later period. The trigonon, the small three stringed harp, first appears under the New Kingdom; in still later times it became very common. This instrument may possibly have been of foreign origin, as was doubtless the lyre. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sibylle Emerit of the Institut français d'archéologie orientale wrote: “The harp has been attested in Egypt since the 4th Dynasty in the musical scenes depicted in the private tombs. It was the favorite instrument of the ancient Egyptians, but this object and its representation seem to have disappeared from the Nile Valley with the advent of Christianity. From the New Kingdom on, several forms of harps coexisted. They led to complex typologies (for instance, the ladle-shaped, boat-shaped, and crescent-shaped harp), but in spite of the large variety, the Egyptian harp was always a vertical type, generally arched and sometimes angular . The fundamental difference between arched and angular harps is that the first one is built from a single wooden piece while the second one requires two.” [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

harp

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: The Egyptian harp was essentially the Sumerian type, only diversified in the dimensions of the sound-box. It is difficult to state where the instrument originated. It seems probable that the Sumero-Elamite instrument, found at Chogha Mish as early as the fourth millennium, and the Egyptian one, which began to appear under the fourth dynasty, had one and the same origin. Or can they both have evolved independently from the more primitive musical bow? A type, inter- mediary between the bow and the harp, has been found in modern Afghanistan, represented on a specimen in the Museum of Arhus University, Denmark and another, uncatalogued, in the former Kunstkammer, Leningrad consists of a bow fixed to an oblong sounding-box. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“The connection is still obvious between the musical bow and the earliest Egyptian harp, with its arched neck comprising the entire length of the instrument and penetrating at the base into the half-ovoid sounding-box, which resembles the gourd resonator attached to the ethnographic musical bow. As in Sumer, the strings end in fastening knobs, not to be confused with the later, rotating pegs. There are never more than nine of these. In the Middle Kingdom, the harps are covered with abundant decoration. In the New Kingdom enormous instruments have as many as eighteen strings and are played standing. The sounding-box now com- prises the whole of the lower half of the instrument. It has not only painted motifs but sometimes also a sculptured head of a pharaoh. A second type is portable, its neck ends in a fine sculptured head, and the curve of the arch is deeply concave. A third category, even lighter, is called by musicologists the ‘shoulder harp’, carried as it is on the left shoulder. To play it the musician holds it either in that position or halfway down his arm, but with the strings still facing outwards, away from him, thus placing it within the category of the vertical harp. The sounding-box is longish: that of a specimen in the Louvre is more than 650 mm. long. Its four strings are attached to a a neck inserted under the hide which must have covered the box; notches are cut in order to avoid slipping. Under the twenty-fifth dynasty the vertical arched harp became more and more concave, until nearly a right angle was formed between the sounding-box and the strings, but the vertical sounding-box is still at the base. ^*^

“Egypt adopted, from the fifteenth century onwards, the vertical angular harp from Babylonia. This became a type in great favour, perhaps owing to the great stability of tuning allowed by the angular structure. The magnificent specimen preserved in the Louvre has been X-rayed: the internal structure of the sounding-box is thus well known. This box was held against the musician’s breast, its lower, tapering half between his thighs. The holder pierces the box above this tapering part. These splendid instruments have twenty-one strings, sometimes even more .” ^*^

Lyres in Ancient Egypt

partially restored lyre

The lyre appears to have been of foreign origin. It shows up only once before the 18th dynasty, and then in the hands of a Bedouin bringing tribute. It is frequently represented after the Egyptians had continuous intercourse with the Semites, and was evidently the fashionable instrument of the New Kingdom. It is found of all sizes and shapes, from the little instruments with five strings, which ladies could easily hold, to those with eighteen strings, some of which were six feet high, the performer having to stand by them. The reader can see lyres of different sizes together with lutes and harps in a picture of a house. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “A lyre, in the wide sense of the term, comprising, in Greece, the kithara and the lyra, is made of a sounding-box of various shapes, from the upper side of which two arms project upwards. The extremities of the arms are joined by a cross-bar. The strings are fastened at the base of the box, then run parallel to the front of it, over a bridge that transmits their vibration to the box, and continue between the arms to be finally twisted round the cross-bar, where their tension can be modified. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“In Egypt the lyre is a foreign instrument. It first appears, as has just been mentioned, in the hands of a Syrian nomad. It is rectangular and usually played with a plectrum. A few centuries later the lyre was fully adopted. It shows more elaborate forms, some- times light and elegant with gracefully contorted arms, sometimes more massive with a rectangular box and a protruding bar at the base for attaching the strings. Some animal ornaments on the arms recall Mesopotamia. Similarly the bow-shaped holder of a large lyre in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, has its parallel, or its model, in the great Babylonian lyre of the Ishali clay plaque. The El Amarna paintings show huge instruments, one of which seems to require two musicians. This compares with the Hittite instrument found at Inandyk described above. It is quite possible, given the political and cultural connections between the Hittites and Egypt, that this type was brought from Anatolia to the Nile valley. Perhaps under the influence of the Palestinian type, some Syrian lyres were modified: one of the arms gets shorter and shorter, the cross-bar more and more slanting, and the strings more and more unequal. This type is frequently depicted in Phoenicia and Assyria, where it sometimes appears along with the traditional, symmetrical type. ^*^

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “The lyre was imported from the Near East during the Middle Kingdom. It is represented for the first time in the tomb of Khnumhotep II in Beni Hassan, carried by a foreigner. This portable instrument, of asymmetric or symmetric shape, became fashionable from the New Kingdom onwards. At that time, mainly women played this instrument, holding it horizontally or vertically, except in Amarna, where men are depicted playing a huge symmetric lyre, placed on the floor or on a base. Two musicians play “quatremain” (playing the lyre at the same time) in a standing position. They wear special clothes: a flounced skirt, a small cape on the shoulders, and a pointed hat, which seem to indicate a Canaanite origin. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Lutes in Ancient Egypt

The lute was also in common use. It’s name — T nefer — is one of the commonest signs in hieroglyphics. Its Egyptian name was derived from a Semitic word and was played by striking it with the plectrum. It appears to originally have had only one string. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “The lute, which was introduced in Egypt at the beginning of the New Kingdom, was also imported from the Near East. This instrument became very popular throughout the Nile Valley and sometimes replaced the harp in depictions accompanying the famous Harper’s Song. Played by male as well as female musicians, it was an instrument with a long neck connected to a sound-box. The lute and the lyre could be played with a plectrum, while the harp could not.” [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: ““A lute has a long neck protruding from the sounding-box. The strings are parallel to the latter, as in the lyre. Moreover, pressure from the fingers on the strings at different levels along the neck shortens at will their vibrating length. Its origin is obscure, but certainly not Sumerian despite two representations. Iran is a possibility because many lutes are represented on terracottas or cylinder seals from Susa. The Babylonian documents show two types of lute. One, rustic, with a very long handle and a small, oval sounding-box as on a cylinder seal in the Louvre; the other is shorter with a more voluminous, nearly rectangular sounding-box. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“The lute has two types of sounding-box: one oval, the second very elongated. Somewhat later it was in favour with the Hittites, who had a third, more elaborate type, the precursor of the modern guitar with frets on the handle and sharing its peculiar shape of body. Generally the ancient lutes have only two or three strings.” ^*^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024