Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

COSMETICS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Duck-shaped kohl spoon In ancient Egypt cosmetics were widely used by both men and women. Black eyeliner was widely used. Ocher was applied for rouge. Oils and creams, often scented, kept skin moist in the dry climate. Sometimes cosmetics were even given as part of one’s wages.

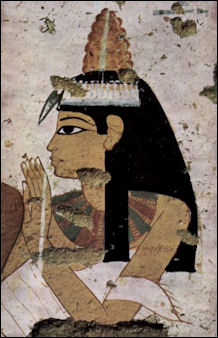

Applying cosmetics to their faces, the oiling of the limbs and hair, was as important to ancient Egyptians as their clothes.In their sculpture also, in which slight deviations from nature were allowed, the Egyptians liked to represent the marks of paint adorning the eyes. It was customary also to paint other parts of the body as well. There is one image of a woman applying rouge while looking at herself in a metal mirror which she holds with the rouge pot in her left hand. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Cosmetics were believed to be imbued with magical powers. Wearing green eye paint, or “ awadju”, was thought to summon the protection of Hathor, the goddess of beauty. Even in death cosmetics were regarded as a key to maintaining a youthful appearance. and the deceased were not happy without seven sorts of salve and two sorts of rouge. ' Among the objects buried with he dead to meet their needs in the afterlife were cosmetics, cosmetic spoons, palettes for on which kohl and ocher could be ground into cosmetics using polished stones, tubes to store eyeliner, jars of moisturizer, ivory hair combs, fragrant cedar and juniper.

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: Scented and moisturizing preparations were widely used for skin and hair, along with cosmetics, in particular green and black eye make-up made from malachite and galena, respectively. Cosmetic lines extending the eyebrows and the outer eye corners can indicate elevated or other-worldly status in art, being applied, for instance, to the king, the gods, and the transfigured dead. Skin color also had symbolic aspects in art: reddish brown paint was typically used to represent men, and light red or yellow for women, although there are a number of exceptions to these general observations. Yellow and white skin color symbolized the shining, bright skin of the gods and the transfigured dead, while deities like Osiris could be shown with black or green skin.” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sacred Luxuries: Fragrance, Aromatherapy, and Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt”

by Lise Manniche and Werner Forman (1999) Amazon.com;

”A Catalogue of Egyptian Cosmetic Palettes in the Manchester University Museum Collection” by Julie Patenaude and Garry J. Shaw (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

"Nefertiti's Face: The Creation of an Icon" by Joyce Tyldesley (Harvard University, 2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume” by Mary Galway Houston (1920) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry” by Carol Andrews (1991) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“Construction of an Ancient Egyptian Wig in the British Museum” by J.Stevens Cox Amazon.com;

“Historical Wig Styling: Ancient Egypt to the 1830s” by Allison Lowery (2019) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Eye Make Up

The Egyptians are credited with inventing eye makeup and were wearing it as far back as 4000 B.C. Both men and women wore eye make up; believing it could cure eye diseases and keep them from falling victim to the evil eye. The most common type, a black ointment known as kohl, was made with soot combined with a lead mineral called galena.. Green eye makeup was made by combining malachite — a green-colored a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral — with galena. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

The Egyptians are credited with inventing eye makeup and were wearing it as far back as 4000 B.C. Both men and women wore eye make up; believing it could cure eye diseases and keep them from falling victim to the evil eye. The most common type, a black ointment known as kohl, was made with soot combined with a lead mineral called galena.. Green eye makeup was made by combining malachite — a green-colored a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral — with galena. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Cheryl Dawley of Minnesota State University, Mankato, wrote: “Eye makeup was probably the most characteristic of the Egyptian cosmetics. The most popular colors were green and black. The green was originally made from malachite, an oxide of copper. In the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.) it was applied liberally from the eyebrow to the base of the nose. In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), green eye paint continued to be used for the brows and the corners of the eyes, but by the New Kingdom it had been superseded by black.

Black eye paint, kohl, was usually made of a sulfide of lead called galena. Its use continued to the Coptic period. By that time, soot was the basis for the black pigment. Both malachite and galena were ground on a palette with either gum and/or water to make a paste. Round-ended sticks made of wood, bronze, haematite, obsidian or glass were used to apply the eye make-up.”[Source: Cheryl Dawley, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

The ancient Egyptians that beauty began with the eyes and, more precisely, the eyelids. They saw them as windows to the soul, Dr. Robert Schwarcz, a New York based OculoFacial Plastic and Reconstructive surgeon told The Daily Beast that “what the Egyptians called the windows to the soul are the first thing people look at.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 23, 2017]

Ancient Egyptian Eye Liner and Eye Shadow

Egyptians wore black eyeliner — known as “mesdemet” of kohl, from Arabic, the world's first mascara — in a circle or oval around their eyes, in part to ward off the evil eye but mainly it seems for the same reason women do it today: to accentuate their eyes and make their beauty pop out. A kind of paste stirred in a jar and moistened with saliva, kohl was generally made from antimony but also from burnt almond shells, fat and malachite, black oxide of copper and brown clay ocher. Applied with ivory, wood or metal sticks, it was also used to darken eyelashes and eyebrows.

Two colors were chiefly used — green, with which under the Old Kingdom they put a line under the eyes; and black, with which they painted the eyebrows and eyelids, in order to make the eyes appear larger and more brilliant. As a cosmetic antimony was chiefly used. It was imported from the East. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Eye shadow was worn on the upper eyelids and lower eyelids. It was usually black or green. Green eye shadow was made of powdered malachite (copper ore). Black came from galena (a dark sulfide of lead); gray was made from calcium carbonate. Goose fat was used as a binder. The ancient Egyptians also wore eye glitter made from the iridescent shells of beetles mixed with powder.

Sarcophagi depict faces with heavy eye-liner. Kohl, which the ancient Egyptians applied like eye-liner, is thought to have used as both a beauty and means of screening out the bright Egyptian sun. On the use of kohl as eye make up, Alastair Sooke wrote for the BBC: “Recent scientific research suggests that the toxic, lead-based mineral that formed its base would have had anti-bacterial properties when mixed with moisture from the eyes. In addition, the heavy application of kohl around the eyes would have helped to reduce glare from the sun. In other words, there were simple, practical reasons why both men and women in ancient Egypt wished to wear eye makeup.[Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016. Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph |::|]

Ancient Egyptian Cosmetic Ingredients

Moisturizing creams and oils were made with bullock bile, whipped ostrich eggs, olive oil, plant resins, fresh milk and sea salt and were scented with frankincense, myrrh, thyme, marjoram and essences of fruit and nuts , particularly almonds. Anti-wrinkle creams were made with wax, olive oil, incense, milk, juniper leavers and crocodile dung.

Analysis of Egyptian make-up turned up galena, cerussite (a white carbonate of lead), , laurionite and phosgenite. Shades of gray were made by mixing galena, which is black, with cerussite laurionite and phosgenite, which are white.

Cosmetic powders usually contained around 10 percent grease which was used to provide texture and help it adhere to the skin. The grease usually came from animal fat, perhaps from geese. Modern cosmetics also contain about 10 percent vegetable fat.

Ancient Egyptian Cosmetic Chemistry

Kohl pot in the form of Bes Analysis of make-up powders found in the tombs of pharaohs who died between 2000 and 1200 B.C. showed they were made of chemical compounds such as laurionite and phosgenite that are not found in nature and are made using complicated process. The analysis was done at the Louvre by chemists from L'Oreal cosmetic company.

L'Oreal chemist Philippe Walter told Discover magazine, "To make laurionite and phosgenite, they couldn't use fire and high temperature. Those compounds are not stable above 170̊C. So they had to use gentler methods involving wet chemistry, the chemistry of solutions."

Walter believes the Egyptians made the compounds using methods like those used by Greeks a millennium later. The Greeks heated the galena to get rid of the sulfur and form a lead oxide, which was mixed with water and salt at a low temperature. Adding water for 40 days or so to keep the pH neutral yields laurionite. using some ground up natron produces phosgenite.

Lead-based eye liner and eye shadow contained oxidized chlorine chemicals that are rare in nature and require the difficult process of wet chemistry to make. Chemists believed that Egyptians went though the trouble to make these chemicals partly to produce cosmetics that had medicinal qualities. Laurionite and phosgenite were used by the Greeks and Romans to treat eye diseases. In ancient Egypt, eyes diseases such as conjunctivitis were very common.

Practical Side of Ancient Egyptian Beauty Aids

Eyeliner not only helped one’s appearance it also helped keep away flies, cut the sun’s glare and contained lead sulfide and chlorine, which acted as disinfectants. There is no evidence of an toxic results from the lead. Ancient Egyptian eye makeup may have been used to warded off infections. Work by Paris-based analytical chemists Philippe Walter and Christian Amatore points that one of its key ingredients — lead — kills bacteria and eye make-up itself may have been used to prevent eye disease.

Alastair Sooke wrote for the BBC: “For modern archaeologists, the ubiquity of beauty products in ancient Egypt offers a conundrum. On the one hand, it is possible that ancient Egyptians were besotted with superficial appearance, much as we are today. Indeed, perhaps they even set the template for how we still perceive beauty. But, on the other, there is a risk that we could project our own narcissistic values onto a fundamentally different culture. Is it possible that the significance of cosmetic artefacts in ancient Egypt went beyond the frivolous desire simply to look attractive? [Source: Alastair Sooke, BBC, February 4, 2016. Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph |::|]

“This is what many archaeologists now believe. Take the common use of kohl eye makeup in ancient Egypt – the inspiration for smoky eye makeup today. Recent scientific research suggests that the toxic, lead-based mineral that formed its base would have had anti-bacterial properties when mixed with moisture from the eyes. In addition, the heavy application of kohl around the eyes would have helped to reduce glare from the sun. In other words, there were simple, practical reasons why both men and women in ancient Egypt wished to wear eye makeup. |::|

“It’s the same with other ancient Egyptian ‘beauty products’. Wigs helped to reduce the risk of lice. Jewellery had powerful symbolic and religious significance. A fired clay female figure, depicting an erotic dancer, excavated at Abydos in Upper Egypt and now in the exhibition at Two Temple Place, is embellished with indentations that were meant to represent tattoos. Of course, in ancient Egypt, tattoos probably had a decorative purpose. But they may have had a protective function too. There is evidence that, during the New Kingdom, dancing girls and prostitutes used to tattoo their thighs with images of the dwarf deity Bes, who warded off evil, as a precaution against venereal disease.” |::|

Ancient Egypt’s Toxic Makeup Fought Infection, Researchers Say

Sindya N. Bhanoo wrote in the New York Times, “The elaborate eye makeup worn by Queen Nefertiti and other ancient Egyptians was believed to have healing powers, conjuring up the protection of the Gods Horus and Ra and warding off illnesses. Science does not allow for magic, but it does allow for healing cosmetics. The lead-based makeup used by the Egyptians had antibacterial properties that helped prevent infections common at the time, according to a report published Friday in Analytical Chemistry, a semimonthly journal of the American Chemical Society. [Source: Sindya N. Bhanoo, New York Times, January 18, 2010]

“It was puzzling; they were able to build a strong, rich society, so they were not completely crazy,” Christian Amatore, a chemist at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and one of the paper’s authors, told the New York Times. “But they believed this makeup was healing — they said incantations as they mixed it, things that today we call garbage.”

Amatore and his fellow researchers, Bhanoo wrote, used electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction to analyze 52 samples from containers of Egyptian makeup preserved at the Louvre. They found that the makeup was primarily made by mixing four lead-based chemicals: galena, which produced dark tones and gloss, and the white materials cerussite, laurionite and phosgenite. Because the samples had disintegrated over the centuries, the researchers were not able to determine what percentage of the makeup was lead.

Cosmetics case Although many written texts, paintings and statues from the period indicate that the makeup was extensively used, Egyptians saw it as magical, not medicine, Dr. Amatore said. In ancient Egypt, during periods when the Nile flooded, Egyptians had infections caused by particles that entered the eye and caused diseases and inflammations. The scientists argue that the lead-based makeup acted as a toxin, killing bacteria before it spread.

As for the use of such chemicals today Amatore said that the toxicity of lead compounds overshadowed the benefits and that there had been many documented cases of poisoning as a result of lead in paints and plumbing in the 20th century. Neal Langerman, a physical chemist and the president of Advanced Chemical Safety, a health safety and environmental protection consulting firm, said, “You probably won’t want to do this at home, especially if you have a small child or a dog that likes to lick you.”

Nonetheless, Dr. Langerman said, it makes sense that the Egyptians were attracted to the compounds. “Lead and arsenic, among other metals, make beautiful color pigments,” he said. “Because they make an attractive color and because you can create a powder with them, it makes sense to use it as a skin colorant.” “It’s the dose that makes the poison,” Dr. Langerman said, in paraphrasing the Renaissance physician Paracelsus. “A low dose kills the bacteria. In a high dose, you’re taking in too much.”

mummy tattoo

In April 2016, scientists announced they had found a 3000-year-old mummy from ancient Egypt heavily tattooed with animals and flower symbols, which are believed to have been sacred and have served to advertise and enhance the religious powers of the woman. Traci Watson wrote in Scientific American: “The newly reported tattoos are the first on a mummy from dynastic Egypt to show actual objects, among them lotus blossoms on the mummy’s hips, cows on her arm and baboons on her neck. Just a few other ancient Egyptian mummies sport tattoos, and those are merely patterns of dots or dashes. Especially prominent among the new tattoos are so-called wadjet eyes: possible symbols of protection against evil that adorn the mummy’s neck, shoulders and back. “Any angle that you look at this woman, you see a pair of divine eyes looking back at you,” says bioarchaeologist Anne Austin of Stanford University in California, who presented the findings at a meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. [Source: Traci Watson, Scientific American, May 5, 2016 /*/]

“Austin noticed the tattoos while examining mummies for the French Institute of Oriental Archaeology, which conducts research at Deir el-Medina, a village once home to the ancient artisans who worked on tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings. Looking at a headless, armless torso dating from 1300 to 1070 B.C., Austin noticed markings on the neck. At first, she thought that they had been painted on, but she soon realized that they were tattoos. /*/

“Austin knew of tattoos discovered on other mummies using infrared imaging, which peers more deeply into the skin than visible-light imaging. With help from infrared lighting and an infrared sensor, Austin determined that the Deir el-Medina mummy boasts more than 30 tattoos, including some on skin so darkened by the resins used in mummification that they were invisible to the eye. Austin and Cédric Gobeil, director of the French mission at Deir el-Medina, digitally stretched the images to counter distortion from the mummy’s shrunken skin. /*/

“The tattoos identified so far carry powerful religious significance. Many, such as the cows, are associated with the goddess Hathor, one of the most prominent deities in ancient Egypt. The symbols on the throat and arms may have been intended to give the woman a jolt of magical power as she sang or played music during rituals for Hathor. The tattoos may also be a public expression of the woman’s piety, says Emily Teeter, an Egyptologist at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute in Illinois. “We didn’t know about this sort of expression before,” Teeter says, adding that she and other Egyptologists were “dumbfounded” when they heard of the finding. /*/

“Some tattoos are more faded than others, so perhaps some were made at different times. This could suggest that the woman’s religious status grew with age, Austin says. She has already found three more tattooed mummies at Deir el-Medina, and hopes that modern techniques will uncover more elsewhere. Even infrared imaging can’t penetrate an intact mummy’s linen binding. But a nineteenth-century penchant for unwrapping mummies could enable the discovery of more tattoos, says Marie Vandenbeusch, a curator at the British Museum in London. Such examples could provide needed evidence “to really pinpoint the use of those tattoos”, she says. /*/

“Austin argues that the scale of the designs, many of them in places out of the woman’s reach, implies that they were more than simple adornment. The application of the tattoos “would’ve been very time consuming, and in some areas of the body, extremely painful”, Austin says. That the woman subjected herself to the needle so often shows “not only her belief in their importance, but others around her as well”.” /*/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo and Livescience (the mummy tattoo)

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024