Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN POSSESSIONS

Queen Hetepheres funerary bed Walls were sometimes decorated with paintings. Mats made from reeds or straw covered the floors. Lamps were comprised of saucers of oil with a wick floating in it. Rich people had beds, stools, couches and chairs. There weren’t many tables. Pillows stuffed with pigeon feathers have been found.

Beautiful chests made of wood, ivory and pottery was used to store linens, cosmetics and jewelry. Some furniture was overlaid with precious metals and inlaid with precious stones and ebony and ivory. Carpets were woven from linen and ornamented with sewn-on patches made from colorful dyed wool. Cosmetic pots often contained kohl, which the ancient Egyptians applied like eye-liner, perhaps to screen out the sun.

Cooking was done in pottery bowls placed in an open fire or in clay ovens. Food and water was stored in large pottery jars. Other possessions included beer jars, glass bottles, trays for sifting grain and flour, fish hooks, flints, flint knives, wine strainers, baskets, and seals inscribed with images of the sun god Amon-Re, the falcon god Horus and Min, the God of fertility.

In ancient India and Egypt ice was sometimes derived from water set in the ground that froze due to cooling evaporation. As early as 3000 B.C., Egyptians were able to make ice in the desert by taking advantage of a natural phenomena that occurs in dry climates. Water left out at night in shallow clay trays on a bed of straw would freeze as a result of evaporation into the dry air and sudden temperatures drops even though the temperature was well above freezing.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Stone Tools in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: Ground Stone Tools, Rock-cut Installations and Stone Vessels from Prehistory to Late Antiquity” by Andrea Squitieri and David Eitam (2019) Amazon.com;

“Culinary Technology of the Ancient Near East From the Neolithic to the Early Roman Period” by Jill L. Baker (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Furniture Volume II: Boxes, Chests and Footstools”

by Geoffrey Killen | Mar 31, 2017 Amazon.com;

“Stone and Metal Vases” by W.M. Flinders Petrie (1853-1942) Amazon.com;

“Old Kingdom Copper Tools and Model Tools” by Martin Odler (2017)

Amazon.com;

”A Manual of Egyptian Pottery, Volume 1: Fayum A - A Lower Egyptian Culture”

by Anna Wodzinska (2011) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Jon Manchip White (2012) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Egypt: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Donald P. Ryan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Ancient Egyptian Mirrors, Fans and Umbrellas

Egyptian mirrors were made from polished metal. They had elaborate handles made in the shapes of animals, flowers and birds. Some had ebony and ivory handles. A copper alloy mirror from the 2nd Millennium B.C. has a handle made out of stone that looks like a column of papyrus.

Tomb paintings and texts, some as old as 3000 B.C., contains images of fans and "fan servants and "royal fan bearers," whose responsibility it was to wave huge fans made from palm fronds or woven papyrus reeds to keep their masters cool.

Umbrellas were used in Mesopotamia as early as 1400 B.C. for protection from the sun not rain and they were also symbols of status and rank. By 1200 B.C. umbrellas became symbols of the god Nut, a celestial goddess who presided over an umbrella-like sky.

Tools in Ancient Egypt

ancient Egyptian mirrors

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “Quite a lot is known about ancient tools thanks to the importance the Egyptians attributed to their use in the next world. The graves of craftsmen often contained tools or models of tools, and tomb walls were at times decorated with scenes of artisans at work demonstrating their techniques. And just to make sure that one would not be left without the necessary implements some had lists of tools carved into the walls. [Source: André Dollinger, Pharaonic Egypt site, reshafim.org.]

“The 6th dynasty official Kaiemankh had such a list: a thousand adzes (an.t), a thousand axes (mjb.t), a thousand mnx-chisels , a thousand DAm.t-chisels, a thousand sA.t-chisels, a thousand gwA-chisels, a thousand saws (tfA). He also did not forget to supply some raw materials like bD.t, apparently chunks of metal (bD refers to a crucible or mould), and Tr, a mineral brought from Elephantine.

“Wood, ivory, bone and stone have been used for making tools since earliest times. Wood has marvellous qualities for which it is used and loved to this day. It combines toughness and pliability and can be given almost any shape. It was part of many tools, generally forming the handle. But some tools were made entirely of wood and remained so through the millennia.

“Ploughs did not have a European-style ploughshare. There was no need to turn over the soil, as the Nile deposited nutrients with every yearly flooding. Used only to break up the topsoil, they continued to be lightly built. Hoes, rakes and grain scoops too were made of wood as were some tools mostly women used, such as spindles and looms. Carpenters' mallets were often just blocks of wood with a handle. Fire drills consisted of a wooden bow and a plant fibre string. Many of these tools changed but little over the centuries. The spindles of the twelfth dynasty for instance had whorl of greater depth than those of the New Kingdom and at the top a long spiral groove for the thread. In Roman times this groove was replaced by a metal hook.”

See Separate Article: TOOLS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MADE OF STONE, METAL AND METEORIC IRON factsanddetails.com

Furniture in Ancient Egypt

pillow According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The typical Egyptian house had sparse furnishings by modern standards. Wood was quite scarce, so large furniture items were not common. By far the most common pieces of furniture were small 3 and 4 leg stools and fly catchers. Stools have been found in common houses as well as in Pharaohs’ tombs. Other items of utilitarian furniture include clay ovens, jars, pots, plates, beds, oil lamps, and small boxes or chests for storing things. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The ever present stool was made from wood, and had a padded leather or woven rush seat. The stools’ 3 or 4 legs were very often carved to look like animal legs. Wealthy people had their stools and all furniture in general was richly decorated with gold or silver leaf. The more common people would have things painted to look more expensive than they were. +\

“The Egyptian bed was a rectangular wooden frame with a mat of woven cords. Instead of using pillows, the Egyptians used a crescent-shaped headrest at one end of the bed. Cylindrical clay ovens were found in almost every kitchen, and the food was stored in large wheel-made clay pots and jars. For common people, food was eaten from clay plates, while the rich could afford bronze, silver, or gold plates. The ruling class also commonly had a throne chair with a square back inlaid with ebony and ivory. Almost everyone also had a chest for storing clothing and a small box for jewelry and cosmetics. Walls were painted, and leather wall hangings were also used. Floors were usually decorated with clay tiles.” +\

See Separate Article: FEATURES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN HOUSES: ROOMS, FURNITURE, GARDENS, DECORATIONS africame.factsanddetails.com

Everyday Items from Tutankhamun’s Tomb

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “In 1922 the discovery of the virtually intact tomb of Tutankhamun became probably the best known and most spectacular archaeological find anywhere in the world. The small tomb contained hundreds of objects (now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo), many richly decorated and covered in gold, that would be needed by the king in his afterlife. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“Tutankhamun's bed: Several beds were found in the tomb (including one that folded up for travelling). This example is of gilded wood, with an intact base of woven string. A headrest would have been used instead of a pillow, and the rectangular board at one end of the bed is a foot-board (not a head-board as in modern beds). The frame of the bed is supported on feline legs. |::|

“Headrest: This elaborate headrest (used instead of a pillow) is made of elephant ivory. When in use, the back of the king's neck would rest on the curved support. The carved figure represents Shu, the god of the atmosphere, and the two lions on the base represent the eastern and western horizons. As well as being a functional object, this headrest has symbolic and ritual meanings too. |::|

“King's firelighter“: Along with all the rich and elaborate objects, the tomb contained some more humble and practical objects, such as this firelighter or fire stick. The end of the spindle would be placed in one of the holes in the base block, and then rotated rapidly by using a bow. The resultant friction on the base board would generate heat, which would ignite dry tinder and start a fire. |::|

See Separate Articles: TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: CONTENTS, ITEMS, TREASURES africame.factsanddetails.com

Feathers in Ancient Egypt

Emily Teeter of the University of Chicago wrote: “Throughout Egyptian history, feathers appear in purely utilitarian settings and also in ritual contexts where they ornament crowns and personify deities. Feathered fans were used to signal the presence of royal or divine beings, and feathers identified certain ethnic types. Feathers are known from representations and also actual examples recovered primarily from tombs. [Source: Emily Teeter, University of Chicago, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Feathers appear frequently in ancient Egyptian iconography, they are are referred to in texts, and they are incorporated into hieroglyphic writing. The prestige and value of feathers is attested by New Kingdom tomb paintings that show foreign delegations from Nubia, Libya, Asia, and Punt laden with exotic merchandise, including feathers. Most commonly shown are what appear to be the wing and tail feathers of ostriches and the wing feathers of falcons; however, it is often difficult to associate the representations with specific species of birds. Feathers were obtained by felling birds with bow and arrow and throw stick, by trapping birds with nets, and through trade.

“As a hieroglyph, the ostrich feather conveyed the phonetic value Sw, and, when used to write a word, served as the ideogram for Swt (feather) and mAat. It could also serve as determinative for mAat. The same sign was used to write the name of the gods Shu and Maat. In Late Period funerary papyri, a female figure with a head in the form of an ostrich feather may represent Maat or in other cases Imentet). In some personification of the West (vignettes of Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, the judges of the deceased wear an ostrich feather on their head symbolizing their ability to determine the truthfulness (maat) of the deceased’s confession. Feathers could be a distinctive feature of gods, such as Behdety, a form of Horus of Edfu, whose epithet is sAb-Swt (“dappled of plumage”) and who is represented by a winged disk.

“Tall narrow feathers in sets of four are used as the identifying headdress of Onuris. A similar arrangement appears on crowns of Amenhotep IV at East Karnak where they may allude to his association with Shu. Less clear is the symbolism of two ostrich plumes that often flank the crown of Osiris and the single or double ostrich feather with a midrib that is characteristic of the atef crown and the crowns of Amun, Isis, the God’s Wife, and some queens. Statues of Ptah and Menkaret from the tomb of Tutankhamen wear garments of feathers.

“In the New Kingdom and later, the deceased may be shown grasping one or more ostrich plumes in each hand, and feathers may also adorn their hair, probably symbolizing that the deceased is imbued with maat. Many royal and private coffins of Dynasty 17 and the New Kingdom are covered with chevron patterns representing a mantle of feathers (rishi), and the feathered wings of the deities Nekhbet and Wadjet encircle the shoulders and chest.

“Semi-circular feathered fans on long handles were held over a divine presence or a divine intermediary to proclaim its presence in processions and festivals. The phonetic value for “fan” was the same as for shade (Swt). In the New Kingdom, Swt became synonymous with the presence of the god, for example, “the shade of Ra had come to rest upon it” or the god’s shade “being upon his head”. A similar feather fan (sryt) served as a military standard for the army and navy. A tall slender fan (bht/xw or xwyt) of a single ostrich plume accompanied the king or members of the royal family as a sign of rank. “Fan bearer on the right of the king” was a prestigious title born by courtiers and princes. Horses who draw the king’s chariot often wear feathered plumes on their heads.

“Feathers that have been identified as ostrich were worn in the hair of Libyans and Nubians. This ethnic association of Nubians with the feather is so close that the text of a Dynasty 20 letter refers to an escort group as “feather-wearing Nubians”. A deposit of ostrich feathers from a campsite at tomb HK 64 at Hierakonpolis is related to both Nubians and Libyans. This group of deliberately arranged feathers was accompanied by an ostracon that refers to the return of the goddess Hathor from the desert. The texts of the Mut Ritual and the Hymn of Hathor from Medamud relate that the goddess was escorted by Libyans and Nubians who offered her ostrich feathers. The HK 64 deposit has been interpreted as the remains of an annual celebration that heralded the return of the goddess.”

Archaeological Evidence of Feathers in Ancient Egypt

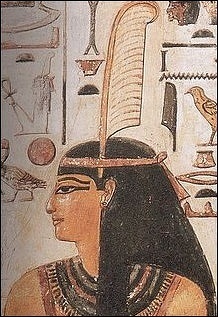

Maat and the feather of truth

Emily Teeter of the University of Chicago wrote: “Only a few examples of feathers are preserved in the archaeological record, and there has been little effort to identify them precisely. What has been described as “large black feathers, possibly the wing or tail feathers of a crow or some such bird” were recovered from a tomb at el-Balabish. Several examples of unidentified feathers, some bound with red-dyed leather (perhaps the remains of fans), were found in C-Group tombs. [Source: Emily Teeter, University of Chicago, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Feathers have been recovered from several New Kingdom tombs. The pillows used to pad the seat of a chair from the tomb of Yuya and Tuya contained what was described as “pigeon feathers” or “down”, and another in the collection of the British Museum is stuffed with “feathers of a waterfowl”. The tomb of Tutankhamen contained eight fans once trimmed with plumes. One fan had alternating brown and white feathers. Although the feathers were not identified by a specialist, their origin is described by decoration on the fan’s semi-circular “palm” that shows scenes of an ostrich hunt and by the inscription on its staff that states that ostriches were bagged by the king while hunting in the desert east of Heliopolis. Another fan from the tomb was fitted with white ostrich plumes.

A hand fan was fitted with well-preserved whitish ostrich feathers that emerged from a shorter row of brown feathers. These fans from the tomb reflect the demand for, and popularity of, ostrich plumes. Carter no. 242 was fitted with 30 plumes, no. 245 with 41, and another with 48. The use of ostrich feathers for these fans, which, according to scenes of royal processions, were held near the head of the king or the deity, may be due not only to the beauty and large size of the feathers, but also because the ostrich plume is the hieroglyph for Maat, the incarnation of truth and cosmic balance. A “carefully laid mass of ostrich feathers” (see above, Feathers as Ethnic Designators) was discovered in a round pit near the central heart of tomb HK 64 at Hierakonpolis. Carbon dating has established a date of the Second Intermediate Period for the deposit. The cache tomb KV 63 in the Valley of the Kings has yielded at least ten pillows stuffed with yet unidentified feathers.

Ostrich Eggshells in Ancient Egypt

Jacke S. Phillips of the School for Oriental and African Studies in London wrote: “Ostriches were hunted in what are now the southern Egyptian, Sudanese, and Libyan deserts for food, feathers, and eggshells from the earliest times. From their eggshells beads, pendants, and vessels were manufactured. Decorated eggshells were used from the Predynastic Period onward and seem to have a religious meaning. [Source: Jacke S. Phillips, School for Oriental and African Studies, London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

ancient Egyptian ostrich egg

“Ostrich eggshell has been recovered at prehistoric and Predynastic sites all along the Nile Valley, and in the Fayum and deserts. Individual eggshells, which can be as large as 170 by 130 mm and 3.5 mm thick, have been found in graves of Naqada I– III and some settlement contexts. A few were decorated and occasionally clay “eggs” were used in lieu; one shell even substituted for the missing head of the deceased. Eggshell jewelry is common from Predynastic times through Dynasty 22, mostly as small disc-beads that were shaped, drilled, and strung as simple necklaces. Larger perforated discs may have been ear, forehead, or clothing ornaments. Pendants, likely having amuletic significance, were perforated at one end and cut to a variety of shapes. Eggshell is sometimes painted, but seems not to have been used as inlays in Egypt.

“Vessels are the only other objects known to have been made from ostrich eggshell. Extremely few are published, but the variety of types chiefly dating to Dynasty 18 include a “container” and cup, both featuring a drilled hole (that on the cup probably intended for a wooden handle), and fragments thought to be a vessel. The added anhydrite neck/rim of a flask from Abydos suggests its date is Dynasty 12 or the Second Intermediate Period, despite its 18th Dynasty context. At least six vessels are reported from Hyksos Period tombs at Tell el-Dabaa. Vessels also were produced earlier despite their extreme rarity in the archaeological record, as attested by an elaborate Dynasty 6 perfume vessel recently found in the Dakhla Oasis, and undoubtedly were used as water containers from earliest times before the production of ceramic vessels. Ostrich eggs were exported to the Aegean from the late Old Kingdom onwards and converted to vessels there.

“In Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt ostrich eggs, sometimes painted, have been found in religious contexts, such as at Berenike. In Coptic Egypt, the egg itself came to symbolize the birth and resurrection of Christ, often decorating the church interior. This symbolism has passed down into both the eastern and western churches.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024