Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

PEOPLE OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN

The study of ancient Egyptian people and life — whether it be homes, food, family life, hair care, child rearing, pets or whatever — is based mostly on identifying scenes associated with each of these activities from monuments, temples and tombs and translating and interpreting the inscriptions and texts found with them. Clues can also be gleaned from artifacts found in burials.

The study of ancient Egyptian people and life — whether it be homes, food, family life, hair care, child rearing, pets or whatever — is based mostly on identifying scenes associated with each of these activities from monuments, temples and tombs and translating and interpreting the inscriptions and texts found with them. Clues can also be gleaned from artifacts found in burials.

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Of the Egyptians themselves, those who dwell in the part of Egypt which is sown for crops practise memory more than any other men and are the most learned in history by far of all those of whom I have had experience: and their manner of life is as follows: — For three successive days in each month they purge, hunting after health with emetics and clysters, and they think that all the diseases which exist are produced in men by the food on which they live. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Egyptians are excessively careful in their observances, both in other matters which concern the sacred rites and also in those which follow... The Egyptians are from other causes also the most healthy of all men next after the Libyans (in my opinion on account of the seasons, because the seasons do not change, for by the changes of things generally, and especially of the seasons, diseases are most apt to be produced in men).

In another respect the Egyptians are in agreement with some of the Greeks, namely with the Spartans, but not with the rest, that is to say, the younger of them when they meet the elder give way and move out of the path, and when their elders approach, they rise out of their seat. In this which follows however they are not in agreement with any of the Greeks — instead of addressing one another in the roads they do reverence, lowering their hand down to their knee. They wear tunics of linen about their legs with fringes, which they call calasiris; above these they have garments of white wool thrown over: woolen garments however are not taken into the temples, nor are they buried with them, for this is not permitted by religion. In these points they are in agreement with the observances called Orphic and Bacchic (which are really Egyptian), and also with those of the Pythagoreans, for one who takes part in these mysteries is also forbidden by religious rule to be buried in woolen garments; and about this there is a sacred story told.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 1: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 2: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 3: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

“Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohs” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen (2009) Amazon.com;

“The African Origin of Civilization” by Cheikh Anta Diop (1974) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic: Rethinking the Origins” by María Victoria Almansa-Villatoro, Silvia Štubňová Nigrelli (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Society” by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

“The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Culture Revealed” by Moustafa Gadalla (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Burden of Egypt” by John A. Wilson (1951) Amazon.com;

“Through a Glass Darkly: Magic, Dreams and Prophecy in Ancient Egypt” (2023)

by Kasia Szpakowska (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

Population of Ancient Egypt

At its height, ancient Egypt only had a population of 1.5 to 2 million people. Large cities in the Near East in the third millennium B.C. had only around 20,000 or 30,000 people. The population density around Amarana — royal city built by Akhnaten to honor the god Atun — was about 500 people per square mile in 1540 BC.

It is estimated that the population of Egypt (the Nile Valle) doubled between 4000 and 3000 B.C. and quadrupled between 4000 B.C. and 2500 B.C., the height of the Old Kingdom, when the pyramids were built. In 1250 B.C. the population of ancient Egypt was about 1.5 times what it was in 2500 B.C. and then it dropped to Old Kingdom levels before the Greco-Roman period.

Methods of birth control mentioned in the Petri Papyrus (1850 B.C.) and Eber Papyrus (1550 B.C.) included coitus interruptus and coitus obstructus (ejaculating into a bladder inserted in a depression at the base of urethra). To keep from having babies, Egyptian women were advised to inset a mixture of honey and crocodile dung in their vagina. The honey may have acted as a temporary cervical cap but the most effective agent was acid in the dung that acted as the world's first spermicide.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

What Did Ancient Egyptians Look Like

It is not known exactly what ancient Egyptians looked like: whether they were white, black or brown. Many scholars believe they probably looked like modern Egyptians.

According to mic.com Despite the mummies, statues and engravings that the ancient Egyptians left behind, there is still much controversy over just what, exactly, they looked like. One thing's for certain though — despite what you might believe about them given Hollywood's whitewashing of Egyptians, the residents of ancient Egypt weren't white [Source: mic.com, April 26, 2016].

According to Slate, they were probably a range of colors, and "neither white nor black" by our contemporary understandings: "Ancient Egypt was a racially diverse place, because the Nile River drew people from all over the region. Egyptian writings do not suggest that the people of that era had a preoccupation with skin color. Those who obeyed the king, spoke the language, and worshipped the proper gods were considered Egyptian."

A book called Chronicle of the Pharaohs shows paintings, scuptures and mummies of 189 pharaohs and leading personalities of Ancient Egypt. Of these, 102 appear European, 13 look black and the rest are hard to classify. All nine mummies look European. The god Nuit was painted as white and blond. A painting from Iteti's tomb at Saqqara shows a very Nordic-looking man with blond hair.

The very first pharaoh, Narmer, also known as Menes, looks very European, The same can be said for Khufu's cousin Hemon, who designed the Great Pyramid of Giza. A computer-generated reconstruction of the face of the Sphinx shows a European-looking face. The Egyptians often painted upper class men as red and upper class women as white; this because the men became sunburned or tanned while outside under the burning Egyptian sun.

Hair and Eye Color of Ancient Egyptians

The mummy of Rameses II has fine silky yellow hair. The mummy of the wife of King Tutankhamen has auburn hair. The tomb of the wife of Zoser, the builder of the first pyramid in Egypt, has a painting of her showing her with reddish-blond hair. Queen Hetop-Heres II, of the Fourth Dynasty, the daughter of Cheops, the builder of the great pyramid, is shown in the colored bas reliefs of her tomb to have been a distinct blonde. Her hair is painted a bright yellow stippled with little red horizontal lines, and her skin is white.

Paintings from the Third Dynasty show native Egyptians with red hair and blue eyes. Amenhotep III's tomb painting shows him as having light red hair. Red-haired mummies were found in the crocodile-caverns of Aboufaida. A blond mummy was found at Kawamil along with many chestnut-colored ones.

A funerary mask with the attributes of the goddess Isis shows a vivid blue-green color of eyes. An Egyptian scribe named Saqqara around 2500 B.C. has blue eyes. A common good luck charm was the eye of Horus, the so-called Wedjat Eye. The eye is always blue, and the word "wedjat" means "blue" in Egyptian. Queen Thi is painted as having a rosy complexion, blue eyes and blond hair.

Concepts of Self in Ancient Egypt

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “The human body is both the physical form inhabited by an individual “self” and the medium through which an individual engages with society. Hence the body both shapes and is shaped by an individual’s social roles. [Source:Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “The human body is both the physical form inhabited by an individual “self” and the medium through which an individual engages with society. Hence the body both shapes and is shaped by an individual’s social roles. [Source:Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The culture of ancient Egypt offers rich resources for analyzing the Egyptians’ conceptualization of the body and the embodied self, in terms of texts and language, pictorial representation, religious beliefs and eschatology, rituals, bodily practices (including grooming and medicine), and social differentiation (such as class, age, and gender). The practice of mummification informs us, not only of the Egyptians’ knowledge of human physiology, but of their conceptualization of the body, which is culturally constructed in every society, while extant physical remains give a much greater insight into the physical anthropology of the populace than is possible for other ancient societies.

“The human being as a complete entity was composed of numerous elements in addition to, or residing in, the physical body. These included fate, the extent of one’s lifetime (aHaw), the name (rn), the shadow (Swt), one’s personal magic (HkAw), the life force (kA), and in some interpretations, the soul (bA). The heart (jb or HAtj) was a metonym for emotion and cognition, and the pumping of the heart was recognized as an indicator of health and life. The jb- heart connoted emotions and cognition, while the HAtj-heart was the physical organ, although the two words could be used interchangeably. An individual was also linked to his parents and ancestors through both the life force (kA) and the physical body, as the expression “heart (jb) of my mother” may suggest (Book of the Dead 30 a - b). Bringing together these elements of the person is a goal expressed in funerary literature and in art, for instance through the symbolism of coffin iconography, including the Four Sons of Horus associated with the integrity of the corpse. A scene from the Ramesside tomb of Amenemhat depicts each of the Four Sons presenting one of these elements to the deceased: Amset bears the heart (jb), Hapi the bA, Duamutef the kA, and Qebehsenuef the XAt-corpse, presaged as a mummy (saH) by being shown in the wrapped form.”

Self-Presentation in Ancient Egypt

Hussein Bassir wrote: In ancient Egypt the primary intention of creating textual self-presentations — or self-portraiture in words, similar to that in paintings, statuary, and reliefs — was to present the explicit characteristics of protagonists in a corresponding fashion, introducing their values and effectiveness to live and rejoice in immortality, both in the afterlife and in the consciousness and thoughts of Egypt’s subsequent generations. The practice of self-presentation was rooted in Egyptian literature from at least the Third Dynasty, and through the course of dynastic history, it differed in aspect, composition, and theme. [Source: Hussein Bassir, an Egyptian archaeologist of Giza Pyramids, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2021]

Self-presentations show the lives of the elites, vividly portraying their beliefs, culture, and expectations for the afterlife. The relationship between royalty and nobility in self-presentations is alluring and informative and compels us to envision the times and the contingencies in which they were created. These texts also make explicit their owners’ wish to be remembered — not forgotten — after death. The presentation of the non-royal self in ancient Egypt represents a window into its culture and historical periods.

Although almost all ancient Egyptian biographies were written in the first person, it is not known whether the protagonists themselves dictated their textual content or one of their family members dictated it on their behalf. Based upon this misunderstanding or assumption, both titles are commonly used: “autobiography,” though we may not be certain whether the work’s author was in fact the protagonist, and “biography,” though we may not be certain of who actually wrote the work — the protagonist or someone else. Baines prefers to employ the term “self-presentation,” rather than autobiography or biography.

Egyptian self-presentations exhibit a holistic approach. They were written in a form that fused genres such as narrative, wisdom literature, funerary literature, and wishes for the afterlife. Self-presentations can be classified into two main types: 1) idealized self-presentations, which present the protagonist as living in perfect accordance with the moral concept of maat; and 2) event-based self-presentations, which reveal significant events the protagonist witnessed or experienced in his professional career, and from which history can often be derived.

The self-presentations of the Fifth Dynasty are particularly informative for their outline of the interactive relationship between the king and the non-royal elite protagonist; this interaction constitutes the subject matter of the self-presentational text. From the end of the Fifth Dynasty and continuing through the Sixth Dynasty, self-presentations detail their protagonists’ careers, including the reigns and state of affairs of the kings under whom they served. The self-presentations of the Sixth Dynasty, especially, reveal the achievements of their owners; as such, they are the forerunners of the laudatory self-presentations of the First Intermediate Period.

The self-presentation at Elkab of Ahmose, son of Abana, who served under a succession of pharaohs in the 17th to 18thDynasties, states: “Now when I had established a household, I was taken to the ship ‘Northern,’ because I was brave. I followed the sovereign on foot when he rode about on his chariot. When the town of Avaris was besieged, I fought bravely on foot in his majesty’s presence. Thereupon I was appointed on the ship ‘Rising in Memphis.’ Then there was fighting on the water in ‘Pjedku’ of Avaris. I made a seizure and carried off a hand. When it was reported to the royal herald the gold of valor was given to me”.

In the following elaborate self-presentation text on the Theban block statue of Twenty-fifth Dynasty official Harwa, it is notable that no royal name is mentioned: “My Lady made me great when I was a small boy, she advanced my position when I was a child. The King sent me on missions as a youth, Horus, Lord of the Palace, distinguished me. Every mission on which their majesties sent me, I accomplished it correctly, and never told a lie about it. I did not rob, I did no wrong, I maligned no one before them. I entered the Presence to resolve difficulties, to assist the unfortunate. I have given goods to the have-not, I endowed the orphan in my town. My reward is being remembered for my beneficence, my ka enduring because of my kindness — Harwa” .

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Non-Royal Self-Presentation” by Hussein Bassir, escholarship.org

Instruction of Ptah-hotep (2200 B.C.) On Being a Good Person

The Instruction of Ptahhotep is an ancient Egyptian literary composition written by the Vizier Ptahhotep, during the rule of King Izezi of the Fifth Dynasty. Regarded as one of the best examples of wisdom literature, specifically under the genre of Instructions that teach something, of Ptahhotep addresses various virtues that are necessary to live a good life in accordance with Maat (justice) and offers insight into Old Kingdom — and ancient Egyptian — thought, morality and attitudes. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “If you desire that your conduct should be good and preserved from all evil, keep yourself from every attack of bad humor. It is a fatal malady which leads to discord, and there is no longer any existence for him who gives way to it. For it introduces discord between fathers and mothers, as well as between brothers and sisters; it causes the wife and the husband to hate each other; it contains all kinds of wickedness, it embodies all kinds of wrong. When a man has established his just equilibrium and walks in this path, there where he makes his dwelling, there is no room for bad humor. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“Be not of an irritable temper as regards that which happens at your side; grumble not over your own affairs. Be not of an irritable temper in regard to your neighbors; better is a compliment to that which displeases than rudeness. It is wrong to get into a passion with one's neighbors, to be no longer master of one's words. When there is only a little irritation, one creates for oneself an affliction for the time when one will again be cool.

“If you are a son of the guardians deputed to watch over the public tranquillity, execute your commission without knowing its meaning, and speak with firmness. Substitute not for that which the instructor has said what you believe to be his intention; the great use words as it suits them. Your part is to transmit rather than to comment upon.

See Separate Article: ETHICS AND VALUES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Customs

The custom of handshaking has been traced back to ancient Egypt. Hieroglyphics, dating back to 2800 B.C., representing the verb "to give," show an extended hand. Kings in ancient Babylon and Assyria grasped the hands of statues of their major Gods during important celebrations and festivals. Kissing the feet, hands of hems of garments of important people was an expression of respect in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

The first known book of manners and correct manners, “The Instructions of Ptahhotep”, was written around 2500 B.C. and a papyrus copy lies a Museum. Known as the "Prisse payrus," it advises guests with their boss to "laugh when he laughs," and "thou shalt be agreeable to his heart." Women are advised to "Be silent it is a better gift than flowers.”

In Genesis 41:41-42 a pharaoh gives Joseph a ring to symbolize a deal has been made. Most ancient rings were made of steatite of medals such as bronze, silver or gold. Few were adorned with precious stones. Some of the oldest known rings were used as signets by rulers, public officials and traders to authorize documents with a stamp. Signatures were not used until late in history.

Herodotus on Egyptian Customs

duality?

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “It is sufficient to say this much concerning the Nile. But concerning Egypt, I am going to speak at length, because it has the most wonders, and everywhere presents works beyond description; therefore, I shall say the more concerning Egypt. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Just as the Egyptians have a climate peculiar to themselves, and their river is different in its nature from all other rivers, so, too, have they instituted customs and laws contrary for the most part to those of the rest of mankind. Among them, the women buy and sell, the men stay at home and weave; and whereas in weaving all others push the woof upwards, the Egyptians push it downwards. Men carry burdens on their heads, women on their shoulders. Women pass water standing, men sitting. They ease their bowels indoors, and eat out of doors in the streets, explaining that things unseemly but necessary should be done alone in private, things not unseemly should be done openly. No woman is dedicated to the service of any god or goddess; men are dedicated to all deities male or female. Sons are not compelled against their will to support their parents, but daughters must do so though they be unwilling. 36.

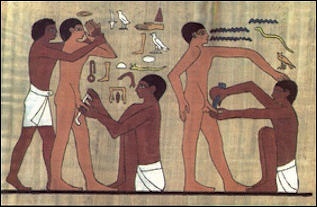

“Everywhere else, priests of the gods wear their hair long; in Egypt, they are shaven. For all other men, the rule in mourning for the dead is that those most nearly concerned have their heads shaven; Egyptians are shaven at other times, but after a death they let their hair and beard grow. The Egyptians are the only people who keep their animals with them in the house. Whereas all others live on wheat and barley, it is the greatest disgrace for an Egyptian to live so; they make food from a coarse grain which some call spelt. They knead dough with their feet, and gather mud and dung with their hands. The Egyptians and those who have learned it from them are the only people who practise circumcision. Every man has two garments, every woman only one. The rings and sheets of sails are made fast outside the boat elsewhere, but inside it in Egypt. The Greeks write and calculate from left to right; the Egyptians do the opposite; yet they say that their way of writing is towards the right, and the Greek way towards the left. They employ two kinds of writing; one is called sacred, the other demotic19. 37.

“They are religious beyond measure, more than any other people; and the following are among their customs. They drink from cups of bronze, which they clean out daily; this is done not by some but by all. They are especially careful always to wear newly-washed linen. They practise circumcision for cleanliness' sake; for they would rather be clean than more becoming. Their priests shave the whole body every other day, so that no lice or anything else foul may infest them as they attend upon the gods.

“Among the Egyptians themselves, those who live in the cultivated country are the most assiduous of all men at preserving the memory of the past, and none whom I have questioned are so skilled in history. They practice the following way of life. For three consecutive days in every month they purge themselves, pursuing health by means of emetics and drenches; for they think that it is from the food they eat that all sicknesses come to men. Even without this, the Egyptians are the healthiest of all men, next to the Libyans; the explanation of which, in my opinion, is that the climate in all seasons is the same: for change is the great cause of men's falling sick, more especially changes of seasons. They eat bread, making loaves which they call “cyllestis,”37 of coarse grain. For wine, they use a drink made from barley, for they have no vines in their country. They eat fish either raw and sun-dried, or preserved with brine. Quails and ducks and small birds are salted and eaten raw; all other kinds of birds, as well as fish (except those that the Egyptians consider sacred) are eaten roasted or boiled. 78.

circumcision

“After rich men's repasts, a man carries around an image in a coffin, painted and carved in exact imitation of a corpse two or four feet long. This he shows to each of the company, saying “While you drink and enjoy, look on this; for to this state you must come when you die.” Such is the custom at their symposia. 79.

“They keep the customs of their fathers, adding none to them. Among other notable customs of theirs is this, that they have one song, the Linus-song,38 which is sung in Phoenicia and Cyprus and elsewhere; each nation has a name of its own for this, but it happens to be the same song that the Greeks sing, and call Linus; so that of many things in Egypt that amaze me, one is: where did the Egyptians get Linus? Plainly they have always sung this song; but in Egyptian Linus is called Maneros.39 The Egyptians told me that Maneros was the only son of their first king, who died prematurely, and this dirge was sung by the Egyptians in his honor; and this, they said, was their earliest and their only chant. 80.

“There is a custom, too, which no Greeks except the Spartans have in common with the Egyptians: younger men, encountering their elders, yield the way and stand aside, and rise from their seats for them when they approach. But they are like none of the Greeks in this: passers-by do not address each other, but salute by lowering the hand to the knee. 81.

“They wear linen tunics with fringes hanging about the legs, called “calasiris,” and loose white woolen mantles over these. But nothing woolen is brought into temples, or buried with them: that is impious. They agree in this with practices called Orphic and Bacchic, but in fact Egyptian and Pythagorean: for it is impious, too, for one partaking of these rites to be buried in woolen wrappings. There is a sacred legend about this. 82.

Eating Customs in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians, Greeks and Romans used towel-like napkins and finger bowls of water scented with things like rose petals, herbs and rosemary. The Egyptians used particular scents — orange blossom, myrrh, almond, cassia — for different courses.

Under the Old Kingdom the Egyptians squatted for their meals," two people generally at one little table, which was but half a foot high, and on which was heaped up fruit, bread, and roast meat, while the drinking bowls stood underneath. They ate with their hands, and had no compunction in tearing off pieces of goose. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

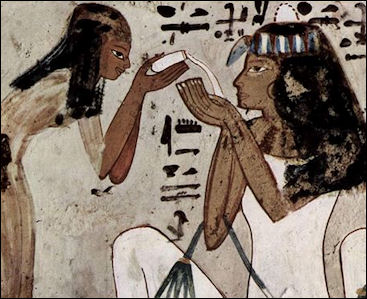

In later times common people ate in the same way, whilst the upper classes of the New Kingdom preferred to sit on high cushioned chairs and to be waited upon by men servants and female slaves. After eating, water was poured over the hands, corresponding to the modern Oriental custom; in the dining-rooms, therefore, we often find a jug and basin exactly like those of a modern wash-stand.

At royal banquets, guests sat on woven mats and drank bowl after bowl of red wine and ate fish, beef, fowl and bread and honey with their fingers. Servant girls washed their hands before they carried in trays of grapes, figs and palm. Beautiful and topless dancers performed to the music of flutes, harps and bone clappers.

Herodotus on Egyptian Distaste for Greek Customs

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “The Egyptians shun using Greek customs, and (generally speaking) the customs of all other peoples as well. Yet, though the rest are wary of this, there is a great city called Khemmis, in the Theban district, near the New City. In this city is a square temple of Perseus son of Danae, in a grove of palm trees. Before this temple stand great stone columns; and at the entrance, two great stone statues. In the outer court there is a shrine with an image of Perseus standing in it. The people of this Khemmis say that Perseus is seen often up and down this land, and often within the temple, and that the sandal he wears, which is four feet long, keeps turning up, and that when it does turn up, all Egypt prospers. This is what they say; and their doings in honor of Perseus are Greek, inasmuch as they celebrate games that include every form of contest, and offer animals and cloaks and skins as prizes. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“When I asked why Perseus appeared only to them, and why, unlike all other Egyptians, they celebrate games, they told me that Perseus was by lineage of their city; for Danaus and Lynceus, who travelled to Greece, were of Khemmis; and they traced descent from these down to Perseus. They told how he came to Khemmis, too, when he came to Egypt for the reason alleged by the Greeks as well—namely, to bring the Gorgon's head from Libya—and recognized all his relatives; and how he had heard the name of Khemmis from his mother before he came to Egypt. It was at his bidding, they said, that they celebrated the games. 92.

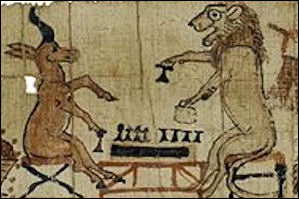

Humor, Sarcasm and Prejudice in Ancient Egyptian Art and Texts

A work called the “Teaching of Ani” penned during the 18th Dynasty offers this advice on drinking: “Do not indulge in drinking beer lest bad words come out of your mouth without you knowing what you are saying. If you fall and hurt yourself, no one will give you a helping hand. Your drinking companions will stand around saying, ‘Out with the drunkard!’ If someone comes to find you and talk to you, you will be discovered lying on the ground like a little child.” [Source: Nathaniel Scharping, Discover, September 22, 2016]

“A strong sarcastic strain comes out here and there, mostly in very small pieces,” Souren Melikian wrote in New York Times. “The ancient Egyptians were not above expressing their dislike of foreigners. Warfare repeatedly pitched the pharaohs against the Semitic states of the Near East. The unknown artist who engraved an ivory plaque destined to adorn a piece of furniture clearly did not have much sympathy for the Assyrians.A prisoner wearing the Assyrian princely attire is depicted raising his arms, tied around the wrists. He seems to be wriggling in a curious quasi-dancing posture. The Assyrian’s goggle-eyed stare makes him a figure of fun. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, May 20, 2011] Relations between the ancient Egyptians and the Nubians who lived south of their territory were not the best either. A small limestone trial piece was dug up at Tell el-Amarna by William Flinders Petrie during his 1891-92 excavation campaign. The sculpture in sunken relief portrays a man with curly hair and exaggerated protruding lips. This is a caricature, definitely not meant to flatter the model.

The museum label dates the small plaque to the reigns of Akhenaten or Tutankhamun, adding that it is “reminiscent of the images of Nubians and West Asians found in Haremhab’s tomb at Saqqara.” At that time Haremhab was still the commander of Tutankhamun’s army. Apparently, the dour general wasted no love on his foes. This was an ethnocentric culture that took an unfavorable view of outsiders.

It is only fair to add that the ancient Egyptians’ sense of fun could sometimes be turned on the sacred symbols of their own religion.Toth, the god of writing, accounting and other intellectual pursuits, was associated with two animals, the baboon and the ibis. A marvelous group on loan from the Louvre, which was carved under Amenhotep III (1389-49 B.C.), portrays the royal scribe Nebmerutef. The official reads a scroll with the faintest smile of concentrated attention. This is a man aware of his power to get things done. Perched on a pedestal next to him, a baboon with bushy eyebrows frowns, creating an irresistibly comical effect.

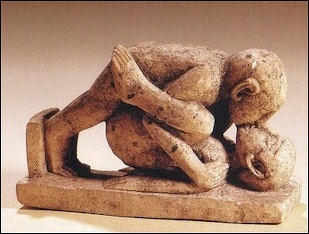

Satirical papyrus Artists retained their sense of fun right down to the end of ancient Egypt. A small turquoise faience baboon, 8.8 centimeters high, is a masterpiece of understated irony, so discreetly wielded that one cannot be absolutely sure that mockery was intended. Seated with its hands resting on its thighs and its penis delicately rendered, the animal stares ahead, with a suggestion of defiance and amusement all at once.

Their humor did not desert Egyptian masters when they portrayed themselves. A wooden statuette of Kery, who was active under Ramesses II (1304-1237 B.C.), hails him as the “great craftsman in the place of truth.” Kery was one of the artists chosen to decorate the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. The master proudly marches on, carrying the standard of “Horus son of Isis, Lord of the desert” on the staff. His happy expression suggests that his prayer for “a good life, combined with health, gladness and rejoicing every day” inscribed on the base had been fulfilled. With his puffed-up cheeks, the craftsman seems about to laugh, despite the solemn tone of his religious invocation that ends “my two eyes seeing, my two ears hearing, my mouth filled with truth.”

Emotions in Ancient Egypt

Angela McDonald wrote: Emotions have been extensively studied across disciplines, but are best defined within specific cultural contexts. In ancient Egypt, they are presented both as visceral experiences that may be “contained” within or transmitted from the heart or stomach, and as socially constructed strands of personhood. Emotions manifest in gestures, postures, and, to a lesser extent, facial expressions in Egyptian art; the presence or absence of their markers in humans may be connected to decorum and status. [Source: Angela McDonald, University of Glasgow, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

Animals are used both in art and script to represent emotional states. Various expressive terms exist to describe emotions linguistically, many of them compounds involving the heart, and emotional states are described in diverse genres of texts throughout time, particularly in New Kingdom love poetry. For the most part, emotions are not depicted on faces in Egyptian art; this is not unexpected since it has long been recognized that art strove to present the eternal, and not the ephemeral.

For Egyptian conceptualizing of emotion, we might usefully look to the body’s center, which was believed to house the organs of thought and feeling. Terms for the heart and the belly show considerable overlap as both organs of the body and as vessels for emotion. In the context of the Coffin Texts, the jb exclusively serves as a metaphorical “container” for the emotions of love and anger, although the HAtjand the Xt may store fear, awe, and dread as forces generated by a fearsome entity. The ancient Egyptians thus seem to have regarded emotions as visceral things, contained within the belly of the self and transmitted into the bellies/bodies of others. A person thought and felt with his heart, reinforcing the intertwining of those two actions, and there is no evidence of a hard and fast distinction made between the physical and the mental aspects of these experiences. This perhaps clarifies why many physical states (heat, cold, roughness, smoothness, etc.) are compounded with-jb to describe internal.

Within Egyptology, individual emotions have been the object of study. Happiness and sadness have been compared in both art and language. Anger as an Egyptianized concept has received considerable attention in the last few years. Depictions of familial affection and grief have been studied from the Amarna Period when, exceptionally, emotions become part of the artistic canon ; grief itself (albeit stylized) is in evidence from the Old Kingdom and bodily expressions of it are commonplace in mourning scenes.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Emotions” by Angela McDonald escholarship.org

Emotions in Ancient Egypt Expressed with Animals and Fruit

Angela McDonald wrote: Animals in love poetry stand again as exemplars of particular emotional states: e.g., a crocodile representing feelings of threat or fear of rejection, and a mouse representing the opposite, a jackal representing lustiness. Very common are tropes that concretize abstract feelings, making them manifest as physical things or sensations: e.g., a series of descriptions on the Deir el-Medina Vessel of love melding with the lover’s body like oil mixing with honey, like fine linen wrapping the body, like incense smoke in the nose. Further, each simile captures an aspect of love embedded in the body: a signet ring on the finger encapsulates its perfect fit, a mandrake in the hand anticipates the pleasure it will bring. All the images presented culminate in the idea that the two lovers will experience togetherness in the same way. [Source: Angela McDonald, University of Glasgow, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

Other senses are often evoked, particularly the senses of smell and taste through images of flowers and fruit. The longing for a loved one evident in love poetry is echoed in texts expressing the longing for particular cities, for the past, and for gods, particularly in the New Kingdom.

Echoing the use of animals in Egyptian art to represent emotions that decorum proscribed in the elite human realm, examples of animal determinatives acting as emotional prototypes abound in script. A mother cow and suckling calf embody the concept of familial affection, just as they do in art; crocodile determinatives are used for a spectrum of terms ranging from the threat of fearsomeness to actual aggression, and various birds epitomize feelings of fearfulness. Most iconically, the trussed goose can be used as a determinative or logogram for the noun snD(fear) and its derivatives, perhaps because the exposed body shows “goosebumps”, but possibly also because it represents the endpoint of the frightening act of strangulation: numerous written (e.g., “I will seize him like a bird so that I may cast fear [snD] into him”: Urk. I. 202.6-7) and visual renderings (Akhenaten strangling a goose) of this act survive, and the sign is used as a determinative for the act of sacrificing birds as offerings as well as the birds themselves throughout history,

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024