Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

PROCESSIONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Scenes from a King's Thirty-Year Jubilee

Processions were a fixture of festivals and funerals in ancient Egypt. Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: “Egyptian processions were performed, and acquired meaning, in a religious context. Funeral processions, for example, symbolized the deceased’s transition into the hereafter. The most important processions, however, were the processions of deities that took place during the major feasts, especially those feasts that recurred annually. The deity left his or her sanctuary on these occasions and thus provided the only opportunities for a wider public to have more or less immediate contact with the deity’s image, although in most cases it still remained hidden within a shrine. These processions often involved the journey of the principal deity of the town to visit other gods, not uncommonly “deceased” ancestor gods who were buried within the temple’s vicinity. The “wedding” of a god and his divine consort provided yet another occasion for a feast for which processions were performed. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“They may be categorized as either processions of deities, in which royal processions would be included, or funeral processions. Processions of deities may be subdivided into those that took place within the temple and those that exited the temple. The former were not open to the wider public but had a profound impact on the architectural design of a temple, because the deity’s statue was carried around to “visit” interior stations or chapels, or—at least from the Late Period onward—the deity’s earthly manifestation was brought to the temple’s roof for the cosmic rejuvenation of the god through ritual unification with the sun, as part of the celebration of the rites of the New Year’s feast. Alongside these internal processional ways, votive statues were erected by the Egyptian elite to guarantee their permanent (even posthumous) presence in the audience whenever a deity epiphanized.

“Although there is clear evidence for feasts in the Old Kingdom, there are neither textual nor archaeological sources that inform us about processions or allow us to trace processional routes in that period. In fact, the bulk of source material dates to the New Kingdom and particularly to the Ptolemaic Period. This bias in the chronological distribution of the surviving material has, consequently, a bearing on the relative validity of our interpretations and reconstructions. Despite this caution, we may surmise that the basic features of processions were similar before, during, and after the New Kingdom.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Royal Festivals in the Late Predynastic Period and the First Dynasty” by Alejandro Jiminez Serrano (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Ritual Year In Ancient Egypt: Lunar & Solar Calendars and Liturgy”

by Mogg Morgan (2014) Amazon.com;

Festivals and Calendars of the Ancient Near East” by Mark Cohen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year: Their Socio-Religious Functions”

by Masashi Fukaya (2020) Amazon.com;

“Reliefs and Inscriptions at Luxor Temple, Volume 1: The Festival Procession of Opet in the Colonnade Hall” (1994) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Food and Festivals” by Stewart Ross (2001) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“The Calendar : The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Biblical Calendar Then and Now: by Bill Bishop and Karen Bishop (2018) Amazon.com

Herodotus on Egyptian Processions and Feasts

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “The Egyptians hold solemn assemblies not once a year, but often. The principal one of these and the most enthusiastically celebrated is that in honor of Artemis at the town of Bubastis31 , and the next is that in honor of Isis at Busiris. This town is in the middle of the Egyptian Delta, and there is in it a very great temple of Isis, who is Demeter in the Greek language. The third greatest festival is at Saïs in honor of Athena; the fourth is the festival of the sun at Heliopolis, the fifth of Leto at Buto, and the sixth of Ares at Papremis. 60. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“When the people are on their way to Bubastis, they go by river, a great number in every boat, men and women together. Some of the women make a noise with rattles, others play flutes all the way, while the rest of the women, and the men, sing and clap their hands. As they travel by river to Bubastis, whenever they come near any other town they bring their boat near the bank; then some of the women do as I have said, while some shout mockery of the women of the town; others dance, and others stand up and lift their skirts. They do this whenever they come alongside any riverside town. But when they have reached Bubastis, they make a festival with great sacrifices, and more wine is drunk at this feast than in the whole year besides. It is customary for men and women (but not children) to assemble there to the number of seven hundred thousand, as the people of the place say. 61.

“This is what they do there; I have already described how they keep the feast of Isis at Busiris. There, after the sacrifice, all the men and women lament, in countless numbers; but it is not pious for me to say who it is for whom they lament. Carians who live in Egypt do even more than this, inasmuch as they cut their foreheads with knives; and by this they show that they are foreigners and not Egyptians. 62.

“When they assemble at Saïs on the night of the sacrifice, they keep lamps burning outside around their houses. These lamps are saucers full of salt and oil on which the wick floats, and they burn all night. This is called the Feast of Lamps. Egyptians who do not come to this are mindful on the night of sacrifice to keep their own lamps burning, and so they are alight not only at Saïs but throughout Egypt. A sacred tale is told showing why this night is lit up thus and honored. 63.

“When the people go to Heliopolis and Buto, they offer sacrifice only. At Papremis sacrifice is offered and rites performed just as elsewhere; but when the sun is setting, a few of the priests hover about the image, while most of them go and stand in the entrance to the temple with clubs of wood in their hands; others, more than a thousand men fulfilling vows, who also carry wooden clubs, stand in a mass opposite. The image of the god, in a little gilded wooden shrine, they carry away on the day before this to another sacred building. The few who are left with the image draw a four-wheeled wagon conveying the shrine and the image that is in the shrine; the others stand in the space before the doors and do not let them enter, while the vow-keepers, taking the side of the god, strike them, who defend themselves. A fierce fight with clubs breaks out there, and they are hit on their heads, and many, I expect, even die from their wounds; although the Egyptians said that nobody dies. The natives say that they made this assembly a custom from the following incident: the mother of Ares lived in this temple; Ares had been raised apart from her and came, when he grew up, wishing to visit his mother; but as her attendants kept him out and would not let him pass, never having seen him before, Ares brought men from another town, manhandled the attendants, and went in to his mother. From this, they say, this hitting for Ares became a custom in the festival32. 64.

“Furthermore, it was the Egyptians who first made it a matter of religious observance not to have intercourse with women in temples or to enter a temple after such intercourse without washing. Nearly all other peoples are less careful in this matter than are the Egyptians and Greeks, and consider a man to be like any other animal; for beasts and birds (they say) are seen to mate both in the temples and in the sacred precincts; now were this displeasing to the god, the beasts would not do so. This is the reason given by others for practices which I, for my part, dislike; 65. but the Egyptians in this and in all other matters are exceedingly strict against desecration of their temples.

Forms of Processions

Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: “During the major religious feasts a procession of the deity exiting the temple was the highlight, because it was the only occasion during which the public, who did not have unrestricted temple access, could have more immediate contact with the deity. The deity’s statue appeared (xaj) by coming forth (prj) from the temple’s sanctuary in a ceremonial bark—hence the two Egyptian terms for procession: sxay (“the causing of a god or ruler to appear”) and prt or prw (“a coming forth”). In most cases the divine image was nevertheless hidden in a naos (shrine) that was carried within the bark and was therefore still invisible to the public. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

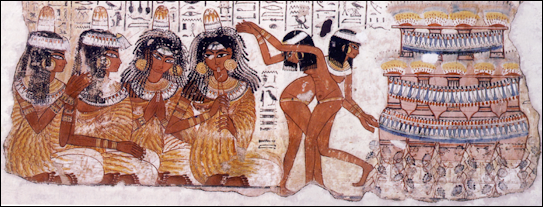

Nebamun tomb fresco dancers and musicians

“On the other hand, reliefs depicting the feasts of the god Min suggest that Min’s image was visible during the procession . In Egyptology it has generally been thought that the divine image in the bark and the cult statue in the sanctuary were one and the same image. However, evidence from Karnak suggests that there were two distinct statues—one that remained in the sanctuary, sSmw jmnw/Dsrw (“hidden/secret/sacred image”), and another that was used as a processional statue, sSmw xw (“the protected image”) or nTr pn Spsj/nTrt tn Spst (“this venerable god/goddess”). The ceremonial bark was not made for actual rowing or sailing, but for being carried on the shoulders of priests, and had carrying poles for that purpose. For sailing on the Nile, Amun’s bark was put onto a boat and pulled by the royal ship.

“The processions that exited a temple for destinations outside the temple precinct usually followed internal processions within the temple and were, with some exceptions, part of the major feasts in an annual cycle. Such feasts usually lasted at least 11 days, although longer durations are also known. Temple reliefs show the outward appearance of these events (including their participants), which comprised five basic elements: 1) the temple’s principal gods (i.e. the triad) in their processional barks; 2) other deities, represented as standards, preceding the barks; 3) the king; 4) the people who formed the audience; and 5) those who acted in the procession. Those who were actively involved were, for example, priests who bore the processional bark, the standards, or other cultic instruments, the rowing crew (needed when the processional bark was actually transported on the Nile in a larger craft), and singers, musicians, and dancers who accompanied the cult statue. The presence of singers implies the existence of standard hymns that were sung—and indeed texts of hymns for the god in procession are preserved. Some processions involved a journey across the Nile River. In a river procession, the Egyptian term for which was Xn(y)t (“rowing”), the ceremonial bark was put into another bark to be ferried over. Necessary rest periods for those who had to carry the bark provided opportunities for the performance of rituals for the deity (e.g., the presentation of offerings, the burning of incense, and the recitation of hymns;

Processions at Major Festivals in Ancient Egypt

Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: “We are particularly well informed about festivals in Thebes due to the documentation provided by the various Theban temples. Some of the associated processions led Amun from his own temple in Karnak, on the east bank, southward to the Luxor temple, or across the river to the temples on the west bank. The occurrence of processions is also suggested by evidence from other sites, such as Memphis, Heliopolis, Thinis, Abydos, and the Nubian sites of Abu Simbel, el-Derr Amada, Gerf Hussein, and Wadi el-Sebua (at some of which Memphite or Theban theology was adapted). That bark processions occurred at each of these sites is not an absolute certainty due to the poor state of preservation of some of the aforementioned places. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Some processions traveled far beyond the temple’s vicinity. The most famous such example is the procession of the goddess Hathor of Dendara, attested in a set of scenes on the pylon of the Ptolemaic temple of Horus at Edfu. Hathor traveled some 180 kilometers upstream from her temple at Dendara to the temple of Horus of Edfu, her divine consort. Her arrival was the starting point of one of Edfu’s five major feasts, each of which lasted for two weeks and was part of a more complex set of feasts and processions in itself. Taking the travel time from Dendara to Edfu and back to Dendara, together with the feast proper, such a procession lasted over several weeks. These events have traditionally been interpreted as constituting a hieros gamos feast, that is, the feast of a divine wedding, celebrating the marriage of Horus and Hathor. This interpretation is now open to doubt. The reliefs and inscription may rather be seen as the depiction of a feast during which the principal deities of Edfu left the temple, together with the newly arrived Hathor, to visit the nearby necropolis, where primordial gods were believed to be buried. In the course of the visit, Horus and Hathor made offerings to these primordial gods and performed rituals to rejuvenate them, thereby stimulating a general regeneration.

funeral procession

“Although every cultic procession had its particular motivations rooted in the local theology, the festal visit of the chief deity to the burial place of his or her ancestors, such as that described above for Edfu, appears to be a feature common to many processions. At Thebes, for example, Amun, in his particular ithyphallic manifestation as Amun of Luxor (that is, Amenope, Jmn-jpt), went from the Luxor temple to the west bank to visit his small temple, 9sr-st, at Medinet Habu. 9sr-st was believed to be the burial place of the particular group of primordial gods known as the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. At 9sr-st, libations and offerings were made in performance of the funerary cult for the Ogdoad. The purpose of the visit, which recurred every ten days rather than annually, was the unification of Amenope, who took the form of the Kamutef-serpent, with the primordial Amun, a member of the Ogdoad. Through this unification the god revitalized himself.

“In the Theban festival of Opet, Amun came forth from his temple in Karnak and went southward to the Luxor Temple, where he received offerings, was recharged with energy thereby, and confirmed the sovereigns’ kingship in return. It has also been speculated that the feast may have celebrated a hieros gamos, as suggested by the prominent role played by the “God’s Wife,” a high-ranking priestess. In the Opet Festival processions Amun either traveled overland or sailed on the river parallel to the bank, apparently depending on the personal preference of the individual ruler. Hatshepsut, for example, took the overland route towards Luxor, then sailed back to Karnak. During her reign (1473 – 1458 B.C.) a processional alley was built as a monumental open space for the ritual performance, the layout allowing for a large crowd to witness the events. This structure connected the Karnak temples of Amun, Amun-Kamutef, and Mut to the temple of Luxor, although its configuration was considerably changed by her successors.

“During the “Beautiful Feast of the Valley,” Amun met with Mut and Khons (the three deities of the Theban Triad) at Karnak, and together they crossed the river to the west bank, where barks carrying the cult statues of the deified Amenhotep I (“Amenhotep-of- the-Forecourt”) and Ahmose-Nefertari joined them. The procession first visited the reigning king’s “house of millions of years” and then proceeded to the houses of millions of years belonging to former rulers, whose barks also joined the group, Accordingly, the itinerary changed with each new sovereign. The procession’s ultimate destination was Deir el- Bahri, which in essence is a sanctuary of Hathor. The deceased of the Theban necropolis were believed to partake in this procession and to benefit from the gods’ passing by their tombs. In the aforementioned Abydene Khoiak festival, the deceased were also thought to benefit from the divine passing by. Horus and Hathor’s journey to the Edfu necropolis is a further parallel.”

Osiris Procession at the Khoiak Festival at Abydos

On the so-called Khoiak Festival at Abydos. Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: “For the Middle Kingdom, the procession of the underworld god Osiris during the Khoiak Festival is well documented. The procession can be reconstructed as follows: It left the god’s temple at Abydos to visit his desert burial place, called Pqr (“Poker”), located in what is known today as Umm el-Qa’ab, the Pre- and Early Dynastic royal necropolis of Abydos. At this site is situated the tomb of 1st-Dynasty king Djer (2974 – 2927 B.C.), which was considered to be that of Osiris from (at least) around 2000 B.C. onward. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Procession to the Tomb of Merymery

“Thus the procession of the deceased royal god Osiris combined both royal and funereal elements. The exact route the procession took to Poker is not entirely certain, but the great number of Middle Kingdom stelae and chapels lining the so-called “terrace of the great god” (rwd n nTr aA) behind the temple of Osiris indicates that here the nSmt, the sacred bark of Osiris, passed by—an indication reinforced by the stelae’s recurrent formula expressing the dedicatees’ hope of seeing the “perfection” (nfrw) of Osiris. Seeing Osiris’s perfection was a symbol of having passed the judgment at death and of having entered the hereafter. The North and Middle cemeteries adjacent to the Abydene “terrace of the great god” may themselves be seen as flanking the processional way into the desert to the aforementioned tomb of Djer.

“The procession’s exact structure, however, is still quite obscure, because the activities of the feast itself were kept secret. The Khoiak Festival probably comprised multiple processions, with the procession of Wepwawet (prt Wp-wAwt) preceding the “great procession” (prt aAt) of Osiris. It is likely that during these processions the myth of Osiris was dramatically re-enacted, or at least recited. Further evidence, consisting of inscriptions and scenes in the Osiris chapels on the roof of the late Ptolemaic-early Roman Hathor temple at Dendara, may give us some idea of these Khoiak “mysteries.” Despite the late date of these attestations there is reason to consider that parts of the texts can be traced as far back as the Middle Kingdom.”

On a festival held in conjunction the Khoiak Festival during Ptolemic and Roman times, Filip Coppens of Charles University, Prague wrote: “The “Festival of the Coronation of the Sacred Falcon” (xaw nswt) was but one of many examples of this type of feast. It was celebrated during the first days of the month of Tybi and is depicted in detail on the inner face of the temple’s enclosure wall. The festival followed almost immediately upon the feasts surrounding the internment and resurrection of the god Osiris, in his role as ruler of Egypt and father of Horus, at the end of the month of Khoiak. On the first day of the fifth month of the year, Horus, as the son and legitimate heir of Osiris, assumed the kingship over the two lands. The annual Festival of the Coronation of the Sacred Falcon can be seen as a re-enactment of both Horus and the ruling pharaoh taking their rightful place upon the throne of Egypt. The main events of this festival consisted of a series of processions within the temple precinct. The main stages of the feast included: a procession of the falcon-headed statue of Horus from the sanctuary to the “Temple of the Sacred Falcon”, located in front of the main temple; the election of a sacred falcon, reared within the temple precinct, as the heir of the god; the display of this falcon (from the platform between the two wings of the pylon) to the crowd of people gathered in front of the temple; the falcon’s coronation in the temple; and, finally, a festive meal in the “Temple of the Sacred Falcon”. Another important festival in the temple of Edfu of which more than the name has been preserved is the “Festival of Victory” (Hb qnt) depicted on the interior of the enclosure wall. [Source: Filip Coppens, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

funeral procession

Political Dimension of Processions

Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: “In addition to their religious significance processions had clear political implications. On the occasion of the Beautiful Feast of the Valley, families gathered at the tombs of their ancestors and held a banquet. The core significance of the Beautiful Feast of the Valley was therefore funerary, yet a strong connection to the royal cult is also evident, demonstrated by the procession’s first destination on the west bank—the reigning king’s house of millions of years—which thus linked the god’s cult with the king’s. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The incidental movements of the ceremonial bark as it traveled upon the priests’ shoulders were seen as being induced by the deity and were consequently interpreted as expressions of divine will. Processions were thus occasions during which the deity gave oracles on a range of concerns—from the problems of everyday life, to the selection of a new ruler, to the legitimization of royal decisions. Hatshepsut is the first individual to report extensively on how Amun selected and enthroned her as king during a procession. Hatshepsut’s instrumentalization of an oracle given during a procession initiated a development resulting in the identification of the feast for Amun’s cosmic rejuvenation with the celebration of the king’s enthronement. Increasingly, political decisions were made not by the sovereign but by Amun, through oracles, some of which were delivered during processions. There is even reason to assume that in the 20th Dynasty some crown princes were selected by the deity. In the demotic fictional narrative The Battle for the Prebend of Amun (Papyrus Spiegelberg), such an oracle to legitimize royal power and activity, given during the occasion of a procession, is described.

“In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), the Theban Opet- procession became a demonstration of royal power and splendor, be it by virtue of the architectural framework or the royal presence at the feast. Furthermore Amun’s rejuvenation during the feast was associated with a regeneration of royal power. In the reign of Ramesses II (and again in the reign of Ramesses III) this rejuvenation was enhanced by the participation of the king’s multitudinous sons, as suggested by temple reliefs. Although it is unlikely that such scenes reflected reality—presumably only some of the princes were present—they nevertheless must have impressively displayed the pharaoh’s vigor and the guaranteed endurance of the dynasty.

“During the Amarna Period all processions were replaced by the royal family’s daily journey from the royal palace to the temple of Aten in Akhetaton (Tell el-Amarna), where the cult was performed. The trek was presented as a divine procession of “a god visiting another god,” followed by an offering procession within the Aten temple. From this perspective, the appearance of the royal family in Amarna constituted the apogee of processions as demonstrations of royal power.”

funeral procession

Processions During Ptolemaic-Roman-Era Temple Festivals

Filip Coppens of Charles University, Prague wrote: “A festive procession could take place within the temple itself, the statues being carried to other chapels or halls inside the temple or to constructions on its roof. The temples ofPtolemaic and Roman Egypt were especially suited for processions inside the temple. The increasing number of enclosure walls that surrounded the temple proper in this period formed a series of corridors that were used for festive processions, which thus took place in the open air but were still hidden from view. The celebration of the “Opening of the Year” (wp-rnpt)—heralding the arrival of the inundation—is an example of a festive procession that took place entirely within the temple walls. This feast of the New Year was a national festival celebrated in all temples, but it is best known from the temples of Edfu and Dendara. Although the specific rites and activities performed differed from place to place (often starting as early as the end of the month of Mesore and proceeding during the five epagomenal days), a general pattern of the processional activities has emerged for New Year’s Day. The statues would be carried in procession from their resting place in temple chapels and crypts to the complex of wabet and court—a set of two chambers consisting of an open court and a slightly elevated chapel—where they were purified, clothed, and adorned. The procession would then continue to a kiosk on the roof of the temple, where, through the ritual of the “opening of the mouth” and the exposure to the sunlight, the statues would be revitalized and reunited with their ba, or “divine power/manifestation”. [Source: Filip Coppens, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Processions with statues were not limited to the interior halls and chapels of the temple, but also regularly took place outside the temple, either within or outside its precinct. These festivals offered the general population the opportunity of closer contact with their deities; thus multitudes of believers would gather along the procession routes, especially when the statues of the gods would leave the precinct. The processions also provided the Egyptians with the opportunity to make use of the oracular powers of their divinities.

“Within the temple precinct, the procession could journey towards the birth temple (“mammisi”) or the sacred lake, among other places. For instance, at the temple of Dendara, a large number of deity-statues often traveled to the bark station and the sacred lake in the month of Tybi, while the goddess Hathor journeyed in procession to the mammisi on no less than six occasions throughout the year.

“Of the processions that took place outside the temple precinct (occasions when the statue of the god would be carried, or sailed, to other temples or sacred sites), the best- known regional example from Ptolemaic times is undoubtedly the “Beautiful Feast of Behdet” (sHn nfr n BHdt). The central themes of this festival, which took place in the month of Epiphi, were fertility and regeneration. It was in essence a popular festival and involved the public more than most other festivals, since it took place largely outside the temple precinct. The festival is described in great detail and depicted on the walls of the open court in the temple of Edfu. It consisted of a 180-kilometer journey that the statue of the goddess Hathor undertook by boat from Dendara to Edfu. On the way to Edfu the procession would halt at several towns, including Thebes and Hierakonpolis, to pay a visit to the deities in the local temples. From Hierakonpolis onwards, the local form of the god Horus would accompany Hathor on her journey to Edfu in his own boat. Numerous pilgrims would gather at these towns to witness the procession of the goddess; other Egyptians would observe the boat of the goddess passing by from the shores of the Nile; and official delegations from, among other places, Elephantine and Hierakonpolis were sent to the final destination, Edfu, to partake in the festival. The central act of the festival was the visit of the main deities of Edfu (Horus and Hathor in particular) to the necropolis of Behdet to bring offerings to Edfu’s ancestor gods. The aim of the rites and acts performed was the regeneration of the ancestor gods, together with a general regeneration of the whole of Egypt.”

funeral procession

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024