Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

TIME IN ANCIENT EGYPT

sundial The Egyptians invented the 24 hour day and helped pioneer the concept of time as an entity. They divided the day into two cycles of 12 hours each. The origin of the 12-hour division might come from star patterns in the sky or from the Sumerian number system which was based on the number 12.

The Mesopotamians invented the 60 minute hour. The idea of measuring the year was more important than measuring the day. People could judge the time of day by following the sun. Judging the time of year was more difficult and important in knowing when to plant crops, expect rain or snow and harvest crops. That is why a yearly calendar was developed before clocks and minutes and seconds didn’t come to the Middle Ages.

The Babylonians have been credited with coming up with the idea of dividing the hour into 60 minutes. The number 60 seemed to be prized especially since 360 divided by six is 60 and some scholars have speculated that is why hours are made up of 60 minutes and minutes are made up of 60 seconds. Other believe the number 60 was arrived at by multiplying the visible planets (5, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) by the number of months (12).

Although Mesopotamians devised the first calenders the Egyptians conceived the modern 365-day, 12 month calendar. Egyptians added five days to the Babylonian 360-day calendar. The ancient Egyptian civil calendar had three season: 1) Akhet (Flooding); 2) Peret (Growing or Sowing); and 3) Shemu (Harvest). Each season had four months with 30 days. The additional five days were tacked onto the end of Harvest and set aside for feasting during the annual flooding of the Nile. The Hindus and Chinese also used 365-day calendars.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Discoverers” by Daniel Boorstin (1985) Amazon.com;

“Time in Antiquity” by Robert Hannah Amazon.com;

“Sundials: Their Theory and Construction” by Albert Waugh (1973) Amazon.com;

“Down to the Hour: Short Time in the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East (Time, Astronomy, and Calendars: Texts and Studies” by Kassandra J. Miller (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Timepiece of Shadows: a History of the Sun Dial”

by Henry Spencer Spackman (1895) Amazon.com;

“The Time Museum, Volume I, Time Measuring Instruments; Part 3, Water-clocks, Sand-glasses, Fire-clocks” by Anthony J. Turner (1984) Amazon.com;

“The Ritual Year In Ancient Egypt: Lunar & Solar Calendars and Liturgy”

by Mogg Morgan (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Calendar : The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

Festivals and Calendars of the Ancient Near East” by Mark Cohen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Biblical Calendar Then and Now: by Bill Bishop and Karen Bishop (2018) Amazon.com

“Dendera, Temple of Time: The Celestial Wisdom of Ancient Egypt” by José María Barrera (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“Royal Festivals in the Late Predynastic Period and the First Dynasty” by Alejandro Jiminez Serrano (2002) Amazon.com;

Clocks in Ancient Egypt

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “In order to tell the time Egyptians invented two types of clock. Obelisks were used as sun clocks by noting how its shadow moved around its surface throughout the day. From the use of obelisks they identified the longest and shortest days of the year. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

An inscription in the tomb of the court official Amenemhet dating to the16th century B.C. shows a water clock made from a stone vessel with a tiny hole at the bottom which allowed water to dripped at a constant rate. The passage of hours could be measured from marks spaced at different levels. The priest at Karnak temple used a similar instrument at night to determine the correct hour to perform religious rites.

Sarah Symons of McMaster University has pointed out that the idea that obelisks at temples as were used as sundials is probably untrue. Yes, there was connection between the obelisks and with the sun: the high point of an obelisk, covered with an alloy of gold and silver, reflected the sun before sunrise. The main function of obelisks, according to obelisk engravings, was to serve honor the pharaoh that commissioned it. Only when obelisks were taken from Egypt and placed in Rome and Paris were they used as a sundials.

After finding one of the world’s oldest sun dials in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, Prof. Susanne Bickel of the University of Basel speculated that people invented the sun dial perhaps to “regulate their work time with the device, or it may relate in some way to the decoration of the royal tombs where the sun’s nightly journey is depicted as structured around a 12-hour system. For now, we can only guess.” [Source Archaeology magazine]

Ancient Egyptian Sun Dials

The ancient Egyptians are thought to have been the first people to develop sun dials although there are some claims the Chinese developed them around the same time. The oldest Egyptian sun dials have been dated at 3500 B.C. A fragment of one at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has been dated to about 3000 B.C. The largest surviving sundial is the 31-meter-high obelisk of Karnak, erected around 1470 B.C. It casts its shadow on a temple of the sun god Amun Ra. A portable Egyptian sundial, or “shadow clock,” that survives from the time of Thutmose III (c. 1500 B.C.) is a horizontal bar about a foot long with a T-shaped structure at one end that casts a shadow on marks on the horizontal bar. In the morning the bar was set with the T facing east; at noon the T was revered and faced west. An example from the 8th century B.C. can be found at the Museum of the Ancient Agora in Athens.

Sun dials were of limited use in cloudy weather (which fortunately for Egyptians was rare) and at night. The sun' shadow moved so slowly it was relatively useless marking off minutes and seconds. Thutmose III era sundials were also useless early in the morning and late in the afternoon when the shadow was cast to an infinite length (this problem was later addressed by Greek sun dials, which were shaped like the interior of the bottom half of a globe).

The other problem with sundials is that they marked off hours that varied in length with the seasons (as the length of the day changed from short in the winter to long in the summer). Egypt is relatively near the equator so the days didn't change that much. Not until the 16th century were sundials marked with true hours, when people acquired pocket sundials as well as clocks.

The Egyptians used "temporary hours" or "temporal hours" which varied in length from day to day depending on what time the sun rose and set. The “Book of That Which Is” describes the 12 sections of the Underworld as each being related to an hour of the night.

Oldest Sundial and Its Use

portable sundial One candidate for the oldest surviving sundial was found in Egypt and dates to around 1450 B.C. Located in the Egyptian museum in Berlin (catalog number 19744), and made of schist , it was probably found in Hermopolis in central Egypt and dates to the reign of Thutmosis III (1479 - 1425 B.C.) during the New Kingdom. The name and titles of the pharaoh are engraved on the side. [Source: http://www.wijzerweb.be/egypteengels.html]

The sundial is shaped like the letter L. The short piece is the gnomon (vertical rod giving a shadow). In the gnomon there is a hole for attaching a small plumb bob. Below is a vertical groove to align the thread of the plumb bob. In the horizontal plane of the long bar there are five circles — marks for the time scale. The distances between the marks are proportional to the numbers 1,2,3,4,5.

In 1910 the German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt hypothesized that the shadow of the gnomon gives an indication of the so-called unequal hours on the time scale. Because in the period between sunrise and sunset is shorter in winter than in summer, the hours are unequal depending on the season. Unequal hours were in use until the Middle Ages. The height of the sun also varies the seasons and this affects the length of the shadow. To give a shadow to the correct mark throughout the year, the gnomon should be variable in height. Therefore Borchardt assumed that the sundial, as it was found, is incomplete and needed a crossbar of a suitable height that served as an adjuster. He surmised these crossbars were lost. In 1965 the Dutch mathematician corroborated Borchardt’s hypothesi to some degree by calculating the shadow of a higher gnomon. He found that a reading from a certain mark was in agreement with reading at the other marks and was a good approximation of the measurement of the unequal hours.

In 1999 Sarah Symons of McMaster University in Ontario Canada defended her doctorate thesis "Ancient Egyptian Astronomy: Timekeeping and Cosmography in the New Kingdom," part of which rejected the theories of Borchardt and Bruins on L-shaped sundials using her knowledge of Egyptian texts and culture and the mathematical background of gnomonics. Symons refutes Borchardt’s theory on four arguments: 1) The sundial hieroglyph shows the L-shape with a small plumb bob, but no crossbar. 2) The calculation of the indications of unequal hours are not measured with a degree of accuracy that merits the addition of a crossbar. 3) Usage of the sundial: The only tool to set up the sundial, is the plumb bob to level it. Directing the sundial with the gnomon towards the sun - the shadow coinciding with the long part of the L-shape over its full width.

4) The text in the Osireon cenotaph name, near the temple of Seti I at Abydos, which describes the construction and usage of such L-shaped sundials. In the text and the accompanying drawing, there is nothing about a crossbar. The simple ratios of the distances between the marks are indicated as corresponding to 3, 6, 9, 12. As in other ancient Egypt drawings, the distances are not drawn to scale. The text describes these relations as "an established procedure.” A passage in the text on the orientation of the sundial can be interpreted in two ways: an east-west orientation with a rotation of 180 degrees at noon or a continuous turning towards the sun.

One of the World's Oldest Sundials Found in Valley of the Kings

ancient Egyptian sundial

In 2013, a team led by Prof. Susanne Bickel of the University of Basel announced that had found one of the world’s oldest sun dials in the Kings’ Valley while clearing the entrance to one of the tombs. A 13th-century limestone sundial found in the Valley of the Kings is one of the earliest timekeeping devices discovered in Egypt — or for that matter the world. Produced during Egypt’s 19th Dynasty and inscribed with black ink, it measures 18 centimeters (7 inches) wide, 15 centimeters (6 inches) tall, three centimeters (1.3 inches) thick. [Source Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

According to Archaeology magazine: Almost 3,500 years ago, men working in the Valley of the Kings, the burial ground for ancient Egypt’s pharaohs and nobility, made a small sundial using a chip of discarded limestone to mark their days. Uncovered by archaeologist Susanne Bickel of the University of Basel in an area where workmen of the 19th Dynasty rested after laboring in the royal tombs, the sundial is one of the earliest such devices ever found in Egypt. Although the men made many drawings in their leisure time — the team even found an image of Ptah, the god of craftsmen and architects — this is the only sundial among the thousands of these chips that have been found. After marking 12 even spaces on the chip, the workmen fixed a wooden or metal stick into the hole at the top to cast a shadow and measure the sun’s progression. Until recently, it was thought that this type of sundial only became common in the Greco-Roman period, at least 1,000 years later.

According to a University of Basel release: “The researchers found a flattened piece of limestone (so-called Ostracon) on which a semicircle in black color had been drawn. The semicircle is divided into twelve sections of about 15 degrees each. A dent in the middle of the approximately 16 centimeter long horizontal baseline served to insert a wooden or metal bolt that would cast a shadow to show the hours of the day. Small dots in the middle of each section were used for even more detailed time measuring. [Source: University of Basel, phys.org, March 15, 2013]

“The sun dial was found in an area of stone huts that were used in the 13th century BC to house the men working at the construction of the graves. The sun dial was possibly used to measure their work hours. However, the division of the sun path into hours also played a crucial role in the so-called netherworld guides that were drawn onto the walls of the royal tombs. These guides are illustrated texts that chronologically describe the nightly progression of the sun-god through the underworld. Thus, the sun dial could also have served to further visualize this phenomenon.”

Bickel told Livescience: “"The significance of this piece is that it is roughly one thousand years older than what was generally accepted as time when this type of time measuring device was used...The piece was found with other ostraca on which small inscriptions, workmen's sketches, and the illustration of a deity were written or painted in black ink. One hypothesis would be to see this measuring device in parallel to the illustrated texts that were inscribed on the walls of the pharaohs' tombs and where the representation of the night and the journey of the sun god through the netherworld is divided into the individual hours of the night. The sundial might have been used to visualize the length of the hours." On the device being used to measure work hours, she said. "I wondered whether it could have served to regulate the workmen's working time, to set the break at a certain time, for example.” [Source: Jeanna Bryner, Live Science, March 20, 2013]

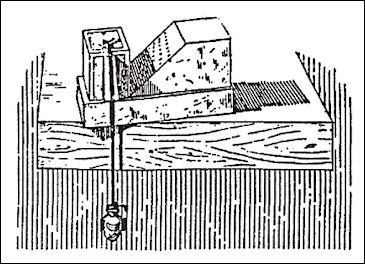

Ancient Egyptian Water Clocks

The ancient Egyptians developed water clocks (useful at night) in the 15th century B.C. Water clocks operate on the principle that water can be made to drip at a fairly constant rate from a bowl with a tiny hole in the bottom. To make sure that time scale remains constant water pressure had to remain constant and an effort had to be made to make sure that the hole in the vessel wasn't worn larger. The clocks were used primarily like hour glasses. Calibrating them to measure off uniform hours at night that were linked to the hours of the day, which changed depending on the season, was too complicated for the ancient Egyptians to deal with.

Daniel Boorstin wrote: the Egyptians had “both outflow and inflow models of water clocks. The outflow type was an alabaster vessel with a scale marked inside and a single hole near the bottom where the water dripped. By noting the drop of the water level inside from one mark to the next mark below on the scale, the passage of time was measured. The later inflow type, which marked the passing time by the rise of water in the vessel, was more complicated, as it required a constant source of regulated supply." [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Creators"]

Time was sometimes determined from lamps. Ancient lamp wicks were timed to last for four hours.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024