Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids)

MIDDLE KINGDOM (2030–1640 B.C.)

The kings of the Twelfth Dynasty restored central government control and a single strong kingship in the period known as the Middle Kingdom. Consisting of the 12th, 13th and part of the 11th dynasties, the Middle Kingdom lasted from around 2030 to 1640 B.C. The period between the Old Kingdom and the New Kingdom — the 1st Intermediate Period (2150 to 2030 B.C.), the Middle Kingdom (2030 to 1640 B.C.) and the 2nd Intermediate Period (1640 to 1540 B.C.) — does not receive that much attention from historians and is largely unknown to the general public. Not that much new or of interest happened. There were some pyramids but no great ones. Art and culture were not all that different that what preceded and came after it. The Middle Kingdom reached its zenith under the 12th Dynasty. The Pharaoh was not then an absolute monarch but rather a feudal lord, and his vassals held their land in their own power.

The Middle Kingdom was a period of decline and then prosperity and economic and political expansion. It consisted of the second part of the 11th dynasty and the 12 and 13 dynasties, with 29 rulers. The Middle Kingdom ended with the invasion of a people called the Hyksos. The Hyksos were Semitic nomads who broke into the Delta from the northeast and ruled Egypt from Avaris in the eastern Delta.The Middle Kingdom pharaohs established their capital first at Lisht near Memphis. Later the capital was moved further south along the Nile to Thebes (Luxor) after a family from Thebes outmaneuvered its rivals and reunified the country around 2000 B.C. and promoted their gods. Egyptian territory expanded during the Middle Kingdom. Nubia was reconquered, forts were built in the south and foreigners from all over the Mediterranean came to live in Egypt.

During the Middle kingdom powerful kings secured the dynastic succession by appointing the heir presumptive as coregent. There were some great kings but none that were famous like King Tut or Ramesses II. The Middle Kingdom was a generally peaceful time. However, expeditions were sent during some phases of the Middle Kingdom to push the borders of Egypt outward. Only during Senusret III do we see numerous campaigns of this type. Senusret III also regained the power that was enjoyed by Mentuhotep I by instituting several internal reforms.

According to the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Egypt annexed Nubia as far south as the second Cataract and built a system of fortresses there. An Egyptian settlement in Sinai worked the mines and included a temple dedicated to the important goddess Hathor. Egypt exercised a strong cultural influence over Palestine and offered political protection to local rulers in the region; ties with Byblos were particularly close. Throughout the Middle Kingdom, Asiatic peoples from Palestine settled in Egypt, especially in the eastern Delta. Close contacts also existed with Crete, which brought goods and craftsmen to Egypt by boat. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DYNASTIES OF THE MIDDLE KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT (2030–1640 B.C.)

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom" edited by Adela Oppenheim, Dorothea Arnold, Dieter Arnold, et al. (2015) Amazon.com;

"The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Society" by Wolfram Grajetzki, Amazon.com;

“Analyzing Collapse: The Rise and Fall of the Old Kingdom” by Miroslav Bárta , Aidan Dodson, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period” by Silke Grallert and Wolfram Grajetzki (2007) Amazon.com;

“Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms”

by Julia Troche (2021) Amazon.com;

“Labour Organisation in Middle Kingdom Egypt, Illustrated, by Micòl Di Teodoro (2018) Amazon.com;

“Rise of the Hyksos: Egypt and the Levant from the Middle Kingdom to the Early Second Intermediate Period” by Anna-Latifa Mourad (2015) Amazon.com;

“Hyksos: A Captivating Guide” Amazon.com;

“The Hyksos: A New Investigation” by John Van Seters (2010) Amazon.com;

Hyksos and Israelite Cites (Classic Archaeological Reprints)

by W. M. Flinders Petrie; J. Garrow Duncan Amazon.com;

The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

List of Rulers from the Middle Kingdom and Intermediate Periods

The 1st Intermediate Period consisted of dynasties 8, 9, 10, and the first half of 11, with a half dozen or so rulers. The Middle Kingdom consisted of the second half Dynasty 11 and dynasties 12 and 13, with 29 rulers. The 2nd Intermediate Period consisted of dynasties 14, 15, 16 and 17, with a dozen rulers.

Turin King List

First Intermediate Period

(ca. 2150–2030 B.C.)

Dynasty 8–Dynasty 10, (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.)

Dynasty 11, first half, (ca. 2124–2030 B.C.)

Mentuhotep I (ca. 2124–2120 B.C.)

Intef I (ca. 2120–2108 B.C.)

Intef III (ca. 2059–2051 B.C.)

Mentuhotep II (ca. 2051–2030 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Middle Kingdom

(ca. 2030–1640 B.C.)

Dynasty 11, second half, (ca. 2030–1981 B.C.)

Mentuhotep II (cont.) (ca. 2030–2000 B.C.)

Mentuhotep III (ca. 2000–1988 B.C.)

Qakare Intef (ca. 1985 B.C.)

Sekhentibre (ca. 1985 B.C.)

Menekhkare (ca. 1985 B.C.)

Mentuhotep IV (ca. 1988–1981 B.C.)

Dynasty 12, (ca. 1981–1802 B.C.)

Senusret I7 (ca. 1961–1917 B.C.)

Amenemhat II (ca. 1919–1885 B.C.)

Senusret II (ca. 1887–1878 B.C.)

Senusret III (ca. 1878–1840 B.C.)

Amenemhat III (ca. 1859–1813 B.C.)

Amenemhat IV (ca. 1814–1805 B.C.)

Dynasty 13, (ca. 1802–1640 B.C.)

Second Intermediate Period

(ca. 1640–1540 B.C.)

Dynasty 14–Dynasty 16, (ca. 1640–1635 B.C.)

Dynasty 17, (ca. 1635–1550 B.C.)

Tao I (ca. 1560 B.C.)

Tao II (ca. 1560 B.C.)

Kamose (ca. 1552–1550 B.C.)

See Separate Article: MIDDLE KINGDOM RULERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Beginning of the Middle Kingdom

Around 2040 B.C. the rulers of Thebes defeated the Heracleopolitan kings, took control of Lower Egypt and reunited Egypt under King Mentuhotep II of Dynasty 11. This dynasty ended when an official, Amenemhet I (around 1991–1962 B.C.), claimed the kingship and founded Dynasty 12, which lasted until around 1783 B.C. and became the classical age of Pharaonic Egypt. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The Middle Kingdom is considered to have started with Nebhepetre Mentuhotep I uniting all of Egypt. He ruled for 51 years and his reign brought much stability to Egypt. His conquest of much of Egypt meant draining the nonarchs of their armies and subsequently their power. This put Nebhepetre Mentuhotep I in such a position as king that had not been realized since Phiops II. His son ruled for some time but eventually Amenemhet I overthrew his grandson, Mentuhotep IV, marking the end of the 11th Dynasty. This apparently required assistance from the nomarchs. Some nomarchs would continue to hold king-like powers until Senusret III stripped them of it. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Achievements During the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt

According to Live Science: At the beginning of this period, a ruler named Mentuhotep II (who reigned until about 2000 B.C.) regained control of the whole country. Pyramid building resumed in Egypt, and a sizable number of texts of literature and science were created. Among the surviving texts is a document now known as the Edwin Smith surgical papyrus, which records a variety of medical treatments that modern-day medical doctors have hailed as being advanced for their time. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

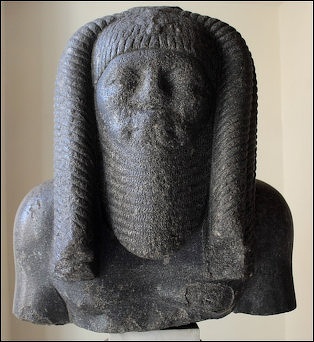

Amenemhet III

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: During the Middle Kingdom trade picked up dramatically and many resources which before had been unused were now being exploited. The Faiyum was exploited for the cultivation of crops, mines which produced gold and quarries were dug for building projects. During the entire Middle Kingdom many building projects were conducted. Mentuhotep I built his mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari. The 12th Dynasty re-established the pyramid building and every Pharaoh of that dynasty was buried in their own pyramid. +\ [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Many other structures were also built during this time. This included the building of fortresses. Amenemhet I built the series of fortresses that came to be known as the Wall of the Princes. Senusret I, built a series of 13 fortresses from the Second Cataract up along the west coast of the Nile to protect against invaders. +\

Problems During the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt

During the Middle Kingdom and the First and Second Intermediate Periods, Egypt became a group of states headed by warlords grouped loosely in confederations of north and south. This schism lasted for 700 years. At the beginning of this period one scholar wrote, "All the pyramids were looted, not secretly at night but by organized bands of thieves in broad daylight...The temples were burned. There was widespread violence. And a desperate famine took hold of the land."

Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt fought against one another. Poverty and hunger became widespread. Inscriptions show droughts, sandstorms and women forced to eat fleas to survive. One inscription read: "I gave bread to those who were hungry and clothes to those who were naked...All of Upper Egypt was dying of hunger, to the point where children were eating their own children." Another read, "The entire country had become like a starved locust."

Food Shortages and Famine in the First Intermediate Period and the Early Middle Kingdom

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “There are frequent allusions to low Nile levels that led to drought and famine in texts of the First Intermediate Period and the early Middle Kingdom. Autobiographical inscriptions of nomarchs of the First Intermediate Period and early Twelfth Dynasty depict these high officials as the saviors of their people in times of crisis, using rhetoric that goes back to Old Kingdom recitals of virtue in mortuary texts. Khety I, nomarch of Assiut during the First Intermediate Period, claims credit for a ten-meter-wide canal, providing irrigation to drought-stricken plowlands through planned water management. In his Beni Hassan tomb-autobiography, Amenemhet (Ameny), nomarch under Senusret I, claims that he preserved his nome in “years of hunger” through wise and fair policies of land management. There is also mention of a food shortage in the Hekanakht Papers. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“These texts suggest that abrupt climate change led to frequent famines, and that nomarchs took a leading role in saving their people because of their access to emergency food supplies, control over the management and conservation of existing food supplies, and access to the engineering skills needed for effective land and water management. Food shortages certainly occurred at times of drought or spoiled harvests, as stored commodities were used up and the new harvest was not yet ready or fit for consumption. What is not clear is whether the texts refer to true famines or temporary shortages in the food supply.

“There is no evidence that any action was taken on the part of the central government to intervene in local affairs; solutions presumably were left to the local officials, water management and the distribution of food being controlled locally. The piety typical of autobiographical inscriptions led officials to boast of virtuous acts that they may not have actually performed. Thus, there is probably much exaggeration in their claims of having saved the populace in times of disaster. While there were certainly occasional food shortages, there is no evidence for the dire conditions described in these autobiographies. There is also no evidence that drought and famine were unique to this period or were of such magnitude that they played a significant role in destabilizing the government at the end of the Old Kingdom. Climate change toward drier conditions at the end of the third millennium B.C. was likely gradual rather than catastrophic.”

Art and Culture During Middle Kingdom (2030–1640 B.C.)

Pectoral of Amenemhat III

During the Middle Kingdom there was a Renaissance of Egyptian culture. Temples were restored and new pyramids were built. Artists and craftsmen produced elaborate gold jewelry and painted wooden sculptures of everyday life. Writers produced some of ancient Egypt's best literature. According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: “The literature and the art of this period were used to promote the royal and elite values and interests. Many of the literary texts of this period have a propagandistic flavor and were circulated to the literati though the temples and schools. The monumental royal inscriptions on temples and other buildings were also used to address the public, to inspire loyalty, and to tell the people of the grandeur of their rulers. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: "The Middle Kingdom (mid-Dynasty 11–Dynasty 13, ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) began when Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II reunited Upper and Lower Egypt, setting the stage for a second great flowering of Egyptian culture. Thebes came into prominence for the first time, serving as capital and artistic center during Dynasty 11. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000 metmuseum.org/ \^/]

“The outstanding monument of this dynasty was Mentuhotep's mortuary complex, loosely modeled on the funerary monuments of his Theban ancestors. Built on a grand scale against the spectacular sheer cliffs of western Thebes, Mentuhotep's complex centered on a terraced temple with pillared porticoes. The masterful design, representing a perfect union of architecture and landscape unique for its time, included painted reliefs of ceremonial scenes and hieroglyphic texts. Carved in a distinctive Theban style also seen in the tombs of Mentuhotep's officials, these now-fragmentary reliefs are among the finest ever produced in Egypt. \^/

“At the end of Dynasty 11, the throne passed to a new family with the accession of Amenemhat I, who moved the capital north to Itj-tawy, near modern Lisht. Strongly influenced by the statuary and reliefs from nearby Old Kingdom monuments in the Memphite region, the artists of Dynasty 12 created a new aesthetic style. The distinctive works of this period are a series of royal statues that reflect a subtle change in the Egyptian concept of kingship.” \^/

Middle Kingdom Pyramids

Dieter Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote : “The pyramid field of Dahshur is located along the western desert edge, 30 kilometers south of Cairo. The site includes two huge stone pyramids built by the Dynasty 4 king Snefru and three smaller Dynasty 12 brick pyramids that belonged to Amenemhat II, Senusret III, and Amenemhat III. The five pyramids are separated by vast areas of desert that contain private mastaba tombs and burials, stone quarries, pyramid construction ramps, causeways, workers' settlements, and other installations. [Source: Arnold, Dieter. "The Pyramid Complex of Senusret III in the Cemeteries of Dahshur", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

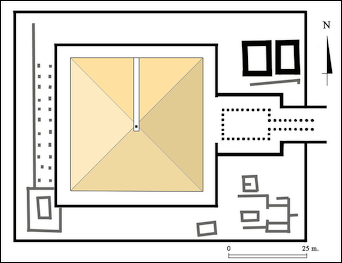

“The Dahshur complex was constructed in two phases. The original complex, which more closely followed Old Kingdom prototypes, included the pyramid, a small pyramid temple to the east, and a stone inner enclosure wall. A second, outer enclosure wall made of brick surrounded six smaller pyramids built for the royal women and a seventh pyramid that served as the king's subsidiary or ka pyramid. Later in the reign of Senusret III, the pyramid complex was enlarged to the north and south, transforming the originally square ground plan into an elongated rectangle. The larger southern extension contained the huge South Temple that seems to have marked the appearance of a new building type in a royal pyramid complex, perhaps replacing or broadening the function of the traditional pyramid temple. \^/

Amenemhet I's pyramid complex

“The plan of Senusret III's apartments under the pyramid closely follows those built by the kings of late Dynasty 5 and Dynasty 6. Senusret III's construction had a long entrance passage, antechamber, crypt, and a room to the side of the antechamber called a serdab by Egyptologists. An unusual feature is the placement of the pyramid entrance, which was not positioned in the north, as was traditional, but in the west. The walls of Senusret III's burial chambers were lined with beautifully finished white limestone, while the crypt was constructed of red granite that was whitewashed. Unlike some Old Kingdom pyramids, the walls were not inscribed with pyramid texts. The crypt contains a finely carved red granite sarcophagus embellished at the base with a pattern that replicates the form of an enclosure wall with palace facade paneling. The absence of any human remains in the tomb, as well as the cleanliness of the interior of the sarcophagus, suggests that Senusret III was not buried in his tomb at Dahshur; instead, the king may have been interred in Abydos, where the king built another mortuary complex. \^/

“The king's pyramid, the burial places of the royal women, and the private tombs surrounding the pyramid complex were plundered during the unstable period of Hyksos rule (ca. 1600 B.C.). The main destruction of the area occurred in the later Ramesside Period (ca. 1295–1186 B.C.), when the pyramids and mastabas were quarried down to their foundations. From the Late Period (712–332 B.C.) onward, the ruined site was used for lower-and middle-class private burials; most of the tombs belong to the late Roman period (ca. 200–350), though Christian burials have also been uncovered. The first large-scale excavation of Senusret III's complex was carried out by the French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan (1857–1924) between 1894 and 1895. The Metropolitan Museum resumed excavation work at the site in 1990 and continues its work in yearly, three-month campaigns.” \^/

Books: Arnold, Dieter The Pyramid Complex of Senusret III at Dahshur: Architectural Studies. With contributions and an appendix by Adela Oppenheim and contributions by James P. Allen. Publications of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition, vol. 26.. New York: n/a, 2002.

Government in the Middle Kingdom

The Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom together represent an important single phase in Egyptian political and cultural development. The Third Dynasty reached a level of competence that marked a plateau of achievement for ancient Egypt. After five centuries and following the end of the Sixth Dynasty (ca. 2181 B.C.), the system faltered, and a century and a half of civil war, the First Intermediate Period, ensued. The reestablishment of a powerful central government during the Twelfth Dynasty, however, re-instituted the patterns of the Old Kingdom. Thus, the Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom may be considered together. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Divine kingship was the most striking feature of Egypt in these periods. The political and economic system of Egypt developed around the concept of a god incarnate who was believed through his magical powers to control the Nile flood for the benefit of the nation. In the form of great religious complexes centered on the pyramid tombs, the cult of the pharaoh, the godking , was given monumental expression of a grandeur unsurpassed in the ancient Near East.*

Central to the Egyptian view of kingship was the concept of maat, loosely translated as justice and truth but meaning more than legal fairness and factual accuracy. It referred to the ideal state of the universe and was personified as the goddess Maat. The king was responsible for its appearance, an obligation that acted as a constraint on the arbitrary exercise of power. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

The pharaoh ruled by divine decree. In the early years, his sons and other close relatives acted as his principal advisers and aides. By the Fourth Dynasty, there was a grand vizier or chief minister, who was at first a prince of royal blood and headed every government department. The country was divided into nomes or districts administered by nomarchs or governors. At first, the nomarchs were royal officials who moved from post to post and had no pretense to independence or local ties. The post of nomarch eventually became hereditary, however, and nomarchs passed their offices to their sons. Hereditary offices and the possession of property turned these officials into a landed gentry. Concurrently, kings began rewarding their courtiers with gifts of tax-exempt land. From the middle of the Fifth Dynasty can be traced the beginnings of a feudal state with an increase in the power of these provincial lords, particularly in Upper Egypt. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Administration in the Late Middle Kingdom

Wolfram Grajetzki of University College London wrote: “The early Middle Kingdom was one of the most decentralized periods of Egyptian history, with many flourishing local centers. In the late Middle Kingdom, these local centers still existed, but the big governors’ tombs and the well-equipped burials of the officials working for them have disappeared. In the late Middle Kingdom, the focus of the royal activities within the country was the Memphite-Fayum region, where all of the royal pyramids were built. Abydos was an important religious center. Especially in the 13th Dynasty, Thebes became the second royal residence of the country. Furthermore, an important population center developed at Avaris (modern Tell el-Dabaa) at the edge of the eastern Delta, where many people coming from the Near East settled. [Source: Wolfram Grajetzki, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Senusret II

“The typical titles of Middle Kingdom local governors are still well attested in the late Middle Kingdom, signifying that the general administrative structures continued and it is unclear what really changed. However, under Senusret III the last bigger tombs for local governors were built, but they are no longer securely attested under Amenemhat III. In the administration new titles appeared, while the long strings of titles for high officials common in almost all other periods of ancient Egyptian history are often just reduced to one title, the function title. Only highest state officials could bear additional ranking titles announcing their social position at the royal court. Titles became more precise: while the title “steward” was common in the other periods, now it often had an extension, such as “steward who counts the ships” or “steward who counts the cattle”. The largest number of scarab seals with name and titles of officials can be dated to the late Middle Kingdom, especially to the 13th Dynasty. Seal impressions of scarabs appear from that time on in great quantities at settlement sites. This seems to reflect a demand for tighter control of commodities.

“From the late Middle Kingdom, a significant number of administrative documents survive, providing valuable insights into parts of the administration. The large number of papyri found at el-Lahun (the pyramid town of Senusret II) also includes religious, mathematical, medical, and literary papyri. From administrative documents, but also from contemporary monuments, it becomes clear that having double names was common in this period. This may be seen in relation to the general trend of this period toward greater control, already visible in the more precise titles and the larger number of sealings used in administration.”

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: “For the most part Egypt's foreign relations remain peaceful during this period as witnessed by the famous tomb painting in the tomb of Khnumhotep ii at Beni Hasan. Part of this painting depicts 37 Asiatics (men, women, and children) bringing eye-paint to Khnumhotep. But there is evidence of international strife during the Middle Kingdom in the Execration Texts. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Religion, Culture and Life in the Late Middle Kingdom

Wolfram Grajetzki of University College London wrote: “Royal and private sculpture often no longer show an idealized image of young men (or women), but depict people of advanced age, maturity, and wisdom. Burial customs underwent a change presumably reflecting development in religious beliefs. Coffins were no longer provided with inner decoration or coffin texts. No wooden models showing food and craft production were placed into the burials, while magical objects used in daily life (magical wands, faience figures) were now included as burial goods. [Source: Wolfram Grajetzki, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Other objects placed into tombs, such as papyri or gaming boards, were taken from work and leisure in daily life. The first shabtis in mummy form and heart scarabs are attested. In contrast, at the highest social level the deceased were equipped with royal insignia otherwise best known from the context of the underworld god Osiris . Mainly from the texts included in these tombs (but also from New Kingdom finds), several literary compositions are known. A number of them were most likely composed in the late Middle Kingdom. Especially several works of “pessimistic” literature, such as the Dialogue Between a Man and His Ba or the Admonitions of Ipuwer, should be mentioned.

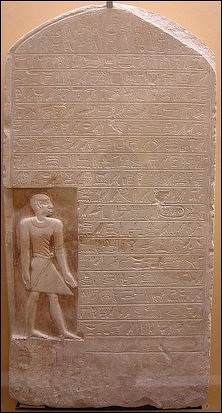

“In private inscriptions mainly on stelae, biographical inscriptions became rare. Now the stela owner is often shown together with colleagues including officials on the same social level, but also socially inferior colleagues working in lower ranks of the administration under the stela owner, while the core family— typical for the early Middle Kingdom— appears less often. Depictions of deities in private context are rare in the early Middle Kingdom. In the late Middle Kingdom, they can appear in the roundel in the uppermost part of private stelae or are depicted in front of the stela owner. The latter stela type often bears hymns to gods. These new features do not appear at exactly the same time; instead, they are a general development over several reigns, from about Senusret III (or even earlier) to the end of the 12th Dynasty and peaking in the early 13th Dynasty.

“Several late Middle Kingdom town sites have been at least partly excavated and provide valuable information on the living conditions of the population. HetepSenusret (el-Lahun) and Wahsut (at Abydos) were planned towns on a grid pattern with large houses for the ruling class in one quarter and smaller ones in others. For the rulers of the late 12th Dynasty, expeditions to the Eastern Desert including Sinai and the Red Sea are well attested. These enterprises left many inscriptions. For the 13th Dynasty, there is less evidence. Expeditions to Sinai are unattested. Only at Wadi el-Hudi, there are a number of inscriptions datable to Sobekhotep IV. There is also some evidence for ongoing activity at Gebel Zeit on the Red Sea coast, covering the late 12th and 13th Dynasties.”

Execration rituals are described in Middle Kingdom tombs. According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: “The Execration Texts were a class of formulas that functioned as destructive magic; they were designed to counteract negative influences, and they are attested from the Old Kingdom through the New Kingdom. The performance of execration rituals centered on objects inscribed to identify the target of the magical act; they were then destroyed or symbolically neutralized. These texts include figures made of unbaked clay and crudely formed into the shape of a bound prisoner. There are three lots of execration texts that deal with Western Asia containing standard formulae with the names of Asiatic chieftains and their related toponyms (place names), after which follows a comprehensive statement of curse along the lines of "all Asiatics of Gns, and their mighty runners … who may rebel … etc." [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Middle of the 13th Dynasty: Stabilization and End

What brought the Middle Kingdom to its ends is not well understood. Internal rivalries may have eroded the central government, and Dynasty 13 consisted of a sequence of short reigns. By around 1640, Egypt had disintegrated into several small kingdoms, a time referred to as the Second Intermediate Period. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Wolfram Grajetzki of University College London wrote: “ The core of the 13th Dynasty starts with some well-attested kings with brief reigns, known from their temple building activities (Amenemhat Sobekhotep II at Medamud) or pyramids.. The vizier Ankhu and the treasurer Senebsumai were in office under these kings. These officials are well known from many monuments and were most likely in office under several rulers. With over 30 scarab seals mentioning his name and title, Senebsumai is one of the best attested Egyptian officials on this type of source. He also appears on more than ten Abydos stelae making him the best attested Middle Kingdom official mentioned on this object type. Papyrus Boulaq 18 belongs to this approximate period. It is an account of the Theban palace written on the occasion of the king’s visit to Thebes and lists the court officials, headed by the vizier Ankhu, and the rations they receive. Under the vizier was a small group of other leading officials with the ranking title “royal sealer,” and the bulk of middle and lower officials working at the royal palace appears in the papyrus. The king’s wife and family are mentioned, but not the king himself. [Source: Wolfram Grajetzki, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

13th dynasty stela

“Another important document from about this time is Brooklyn Papyrus 35.1446 also from Thebes, dealing with the “great enclosure”, the name of the institution that organized corvée. This document is one of the main attestations for corvée, i.e., labor. It seems that most Egyptians had to work for a certain time span in different types of state projects. The back of the document lists about ninety serfs including a large number of textile weavers. The great amount of Asiatic names in that list is remarkable and demonstrates how many foreigners from that region seem to have lived at Thebes. Although one has to be careful with concluding ethnic identity from a list of names only, the large number of foreigners in late Middle Kingdom Egypt is also attested by other sources.

“Four long-reigning kings followed, with two or three short-reigning kings in between. Neferhotep I, Sobekhotep IV, Ibia, and Aye ruled a total of about 50 years. While the first two kings are well known from monuments throughout the country, the two others are mainly known from a large number of scarab seals. Neferhotep I and Sobekhotep IV, who reigned together for about 20 years, were brothers coming from a family of officials. Their grandfather Nehy was “soldier of the town regiment,” a military official from a mid level of command. A copious amount of private stelae is datable under these two kings. They no longer bear the king’s name in the roundel of the stelae or a date, but some officials are featured in rock inscriptions together with the kings under which they served, and that enables the reconstruction of a dense network of officials.

“No such evidence is available for the reigns of Wahibra Ibia and Merneferra Aye. The latter king is the last attested on monuments from Upper and Lower Egypt. The pyramidion of his pyramid was found in Tell el-Dabaa. All following kings assigned to the 13th Dynasty are only known from monuments found in Upper Egypt. Parts of the eastern Delta with Tell el-Dabaa as center were taken over by local kings—perhaps of Near Eastern origin—and the unity of the country ended. However, the timing of the development is uncertain. The end of the 13th Dynasty and its relation to the following dynasties remains highly enigmatic. It can only be said with certainty that at one point the court moved from Itytawy in the north to Thebes in the south, while the Hyksos seem to have ruled in the north.”

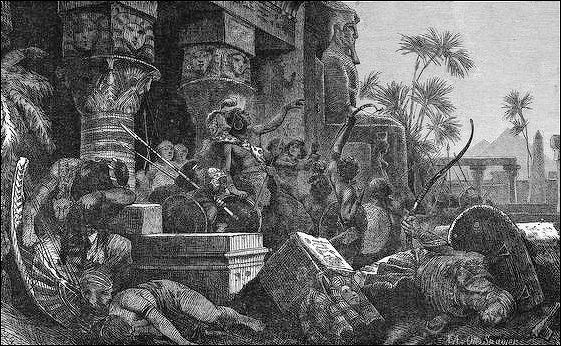

Hyksos Invade Ancient Egypt

Around 1700 B.C., the Hyksos — a mysterious Semitic tribe from Caucasia in the northeast — invaded Egypt from Canaan and routed the Egyptians. The Hyksos were a chariot people. They and the Hittites were the first people to use chariots in the Middle East, an advancement that gave them an advantage over the people they conquered. The Hyksos introduced the horse and chariot to the Egyptians, who later used them to expand their empire. In Egyptian the word Hyksos means “ruler of foreign lands”.

Hyksos rule over Egypt was relatively brief. They established themselves for a while in Memphis and exactly how they came to power is not clear. Later they established a capital in Avaris, along the Mediterranean in the Nile Delta. During the Second Intermediate Period they ruled northern Egypt while Thebes-based Egyptians ruled southern Egypt. In the 2nd Intermediate Period, the four rulers during 15 and 16 dynasties were Hyksos. The Hyksos were thrown out of Egypt in 1567 B.C.

The Hyksos are sometimes referred to as the Shepherd Kings or Desert Princes. In the A.D. 1st century The Roman-Jewish historian Josephus described the Hyksos as sacrilegious invaders who despoiled the land. One ancient text on the Hyksos reads: “Hear ye all people and the folk as many as they may be, I have done these things through the counsel of my heart. I have not slept forgetfully, (but) I have restored that which has been ruined. I have raise up that which has gone to pieces formerly, since the Asiatics were in the midst of Avaris of the Northland, and vagabonds were in the midst of them, overthrowing that which had been made. They ruled without Re, and he did not act by divine command down to (the reign of) my majesty. (Now) I am established upon the thrones of Re....” [Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” Princeton, 1969, web.archive.org, p. 231]

Chronicles that portray Hyksos rule as cruel and repressive were probably Egyptian propaganda. More likely they came to power within the existing system rather than conquering it and ruled by respecting the local culture and keeping political and administrative systems intact. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “The Hyksos presented themselves as Egyptian kings and appear to have been accepted as such. They tolerated other lines of kings within the country, both those of the 17th dynasty and the various minor Hyksos who made up the 16th dynasty.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Hyksos invasion by 19th-century artist Hermann Vogel

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024