Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

TWENTY-SIXTH DYNASTY OF ANCIENT EGYPT

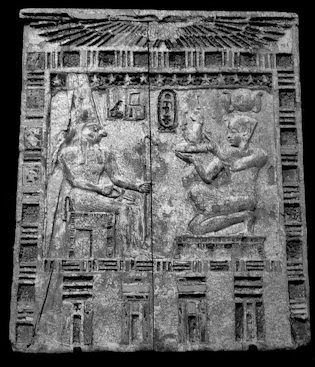

26th dynasty art

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty was founded by Psammethichus I, who made Egypt a powerful and united kingdom. This dynasty, which ruled from 664 to 525 B.C., represented the last great age of pharaonic civilization. The dynasty ended when a Persian invasion force under Cambyses, the son of Cyrus the Great, dethroned the last pharaoh. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Psamtek I reunited Egypt under Egyptian control and freed it from the Assyrians, thus inaugurating the 26th Dynasty and the Saite period. He reformed Egypt’s government and removed the last vestiges of the Kushite rule. Psamtek, Necho )Neko) II and Amose II carried out numerous building programs, including an ambitious scheme by Necho II (Necho II) to link the Red Sea and the Nile by digging a canal through the Wadi Tumilat.

“Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “After their invasion, the Assyrians soon withdrew from Egypt, leaving power in the hands of Psametik I (664-610 B.C.), ruler of the city of Sais in north-western Egypt. His dynasty followed that of the Nubians in its promotion of the past as a model for the present, much of its artwork being inspired by, or copied from, ancient models. Unfortunately, although the Assyrians were no longer a threat, the Persians took over Egypt in the reign of Psametik III... This take-over spelt the beginning of the end for Egypt as an independent nation.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egypt of the Saite Pharaohs, 664–525 BC” by Roger Forshaw (2019) Amazon.com;

“Jeremiah's Egypt: Prophetic Reflections on the Saite Period” by Aren M. Wilson-Wright | (2023) Amazon.com;

“Primary Sources, Historical Collections: Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies”

by Budge Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis (2023) Amazon.com;

“Saite Forts in Egypt: Political-Military History of the Saite Dynasty”

by Květa Smoláriková (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies” (Classic Reprint) by E. A. Wallis Budge Amazon.com;

“The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt, 1100-650BC” by Kenneth Kitchen (1996) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Inscriptions from Egypt's Third Intermediate Period” by Robert Kriech Ritner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Egypt in the Third Intermediate Period”

by James Edward Bennett (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

26th Dynasty Kings

The founder of the 26th dynasty, Psammetichus I (around 664–610 B.C.) strengthened Egypt by the widespread employment of foreigners – Greek and Jewish mercenary troops and Phoenician sailors and merchants. During his reign or that of Psammetichus II (around 595–89 B.C.) the famous colony of Jewish mercenary soldiers was established at Elephantine to protect the southern frontier of Egypt.

Psamtek (Psammetichus) I controlled Thebes by appointing his daughter, Nitocris, there as "divine votaress" of Amon. Psamtek I's success was due in part to the help of Greek (Ionian and Carian) mercenaries in his army, and as Assyria declined, Egypt's contacts with foreign countries grew. Greeks were given a free trading port at Naucratis in the Delta, and Psamtek I led troops to Palestine. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

mummy from the Saite Period

Dynasty 26 (Saite) Kings, 688–252 B.C.

Nikauba: 688–672 B.C.

Necho I: 672–664 B.C.

Psamtik I: 664–610 B.C.

Necho II: 610–595 B.C.

Psamtik II: 595–589 B.C.

Apries: 589–570 B.C.

Amasis: 570–526 B.C.

Psamtik III: 526–525 B.C.

Necho II (610–595 B.C.) continued these policies, campaigning unsuccessfully against the Chaldaeans under Nebuchadnezzar and defeating King Josiah of Juda. Subsequently, the Egyptian kings Apries (589–570) and Amasis (570–526) also struggled against the Chaldaeans. Necho II defeated the army of Josiah of Judah but was later was defeated by the Babylonian armies of Nebuchadnezzar. Necho II is regarded as one of the most significant Late Kingdom rulers. He came to the throne in 658 B.C. ) and recruited the displaced Ionian Greeks to form an Egyptian navy. His capture of Palestine is described in The Bible in the second Book of Kings. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Saite Kings

James Allen and Marsha Hill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “When the Assyrians withdrew after their final invasion, Egypt was left in the hands of the Saite kings, though it was actually only in 656 B.C. that the Saite king Psamtik I was able to reassert control over the southern area of the country dominated by Thebes. For the next 130 years, Egypt was able to enjoy the benefits of rule by a single strong, native family, Dynasty 26. Elevated to power by the invading Assyrians, Dynasty 26 faced a world in which Egypt was no longer concerned with its role in international power politics but with its sheer survival as a nation. The Egyptians, however, still chose to think of their land as self-contained and free from external influence, unchanged from the days of the pyramid builders 2,000 years earlier. In deference to this ideal, the Saite pharaohs deliberately adopted much from the culture of earlier periods, particularly the Old Kingdom, as the model for their own. Later generations would remember this dynasty as the last truly Egyptian period and would, in turn, recapitulate Saite forms. [Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Under Saite rule, Egypt grew from a vassal of Assyria to an independent ally. There were even echoes of the bygone might of Egypt's New Kingdom in Saite military campaigns into Asia Minor (after the collapse of the Assyrian empire in 612 B.C.) and Nubia. In pursuit of these goals, however, the Saite pharaohs had to rely on foreign mercenaries—Carian (from southwestern Asia Minor, modern Turkey), Phoenician, and Greek—as well as Egyptian soldiers. These different ethnic groups lived in their own quarters of the capital city, Memphis. The Greeks were also allowed to establish a trading settlement at Naukratis in the western Delta. This served as a conduit for cultural influences traveling from Egypt to Greece. The conquest of Egypt by Persia brought an end to the Saite dynasty and native control of Egypt.

Herodotus on Psammetichus (Psamtik I: 664–610 B.C.)

Psammetichus — better known today as Psamtik I — was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664–610 B.C. The great Greek historian Herodotus (484 – c. ... 425 B,C.) wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “This Psammetichus had formerly been in exile in Syria, where he had fled from Sabacos the Ethiopian, who killed his father Necos; then, when the Ethiopian departed because of what he saw in a dream, the Egyptians of the district of Saïs brought him back from Syria. Psammetichus was king for the second time when he found himself driven away into the marshes by the eleven kings because of the helmet. Believing, therefore, that he had been abused by them, he meant to be avenged on those who had expelled him. He sent to inquire in the town of Buto, where the most infallible oracle in Egypt is; the oracle answered that he would have vengeance when he saw men of bronze coming from the sea. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Psammetichus did not in the least believe that men of bronze would come to aid him. But after a short time, Ionians and Carians, voyaging for plunder, were forced to put in on the coast of Egypt, where they disembarked in their armor of bronze; and an Egyptian came into the marsh country and brought news to Psammetichus (for he had never before seen armored men) that men of bronze had come from the sea and were foraging in the plain. Psammetichus saw in this the fulfillment of the oracle; he made friends with the Ionians and Carians, and promised them great rewards if they would join him and, having won them over, deposed the eleven kings with these allies and those Egyptians who volunteered. 153.

“Having made himself master of all Egypt, he made the southern outer court of Hephaestus' temple at Memphis, and built facing this a court for Apis, where Apis is kept and fed whenever he appears; this court has an inner colonnade all around it and many cut figures; the roof is held up by great statues twenty feet high for pillars. Apis in Greek is Epaphus. 154.

“To the Ionians and Carians who had helped him, Psammetichus gave places to live in called The Camps, opposite each other on either side of the Nile; and besides this, he paid them all that he had promised. Moreover, he put Egyptian boys in their hands to be taught Greek, and from these, who learned the language, are descended the present-day Egyptian interpreters. The Ionians and Carians lived for a long time in these places, which are near the sea, on the arm of the Nile called the Pelusian, a little way below the town of Bubastis. Long afterwards, king Amasis removed them and settled them at Memphis to be his guard against the Egyptians. It is a result of our communication with these settlers in Egypt (the first of foreign speech to settle in that country) that we Greeks have exact knowledge of the history of Egypt from the reign of Psammetichus onwards. There still remained in my day, in the places out of which the Ionians and Carians were turned, the winches64 for their ships and the ruins of their houses. This is how Psammetichus got Egypt. 155.

“I have often mentioned the Egyptian oracle, and shall give an account of this, as it deserves. This oracle is sacred to Leto, and is situated in a great city by the Sebennytic arm of the Nile, on the way up from the sea. Buto is the name of the city where this oracle is; I have already mentioned it. In Buto there is a temple of Apollo and Artemis. The shrine of Leto where the oracle is, is itself very great, and its outer court is sixty feet high. But what caused me the most wonder among the things apparent there I shall mention. In this precinct is the shrine of Leto, the height and length of whose walls is all made of a single stone slab; each wall has an equal length and height; namely, seventy feet. Another slab makes the surface of the roof, the cornice of which is seven feet broad. 156.

“Thus, then, the shrine is the most marvellous of all the things that I saw in this temple; but of things of second rank, the most wondrous is the island called Khemmis. This lies in a deep and wide lake near the temple at Buto, and the Egyptians say that it floats. I never saw it float, or move at all, and I thought it a marvellous tale, that an island should truly float. However that may be, there is a great shrine of Apollo on it, and three altars stand there; many palm trees grow on the island, and other trees too, some yielding fruit and some not. This is the story that the Egyptians tell to explain why the island moves: that on this island that did not move before, Leto, one of the eight gods who first came to be, who was living at Buto where this oracle of hers is, taking charge of Apollo from Isis, hid him for safety in this island which is now said to float, when Typhon came hunting through the world, keen to find the son of Osiris. Apollo and Artemis were (they say) children of Dionysus and Isis, and Leto was made their nurse and preserver; in Egyptian, Apollo is Horus, Demeter Isis, Artemis Bubastis. It was from this legend and no other that Aeschylus son of Euphorion took a notion which is in no poet before him: that Artemis was the daughter of Demeter. For this reason the island was made to float. So they say. 157.

“Psammetichus ruled Egypt for fifty-three years, twenty-nine of which he spent before Azotus, a great city in Syria, besieging it until he took it. Azotus held out against a siege longer than any city of which we know. 158.

Herodotus on Psammetichus’s Experiment on Language and Children

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Now before Psammetichus became king of Egypt,1 the Egyptians believed that they were the oldest people on earth. But ever since Psammetichus became king and wished to find out which people were the oldest, they have believed that the Phrygians were older than they, and they than everybody else. Psammetichus, when he was in no way able to learn by inquiry which people had first come into being, devised a plan by which he took two newborn children of the common people and gave them to a shepherd to bring up among his flocks. He gave instructions that no one was to speak a word in their hearing; they were to stay by themselves in a lonely hut, and in due time the shepherd was to bring goats and give the children their milk and do everything else necessary. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Psammetichus did this, and gave these instructions, because he wanted to hear what speech would first come from the children, when they were past the age of indistinct babbling. And he had his wish; for one day, when the shepherd had done as he was told for two years, both children ran to him stretching out their hands and calling “Bekos!” as he opened the door and entered. When he first heard this, he kept quiet about it; but when, coming often and paying careful attention, he kept hearing this same word, he told his master at last and brought the children into the king's presence as required. Psammetichus then heard them himself, and asked to what language the word “Bekos” belonged; he found it to be a Phrygian word, signifying bread. Reasoning from this, the Egyptians acknowledged that the Phrygians were older than they. This is the story which I heard from the priests of Hephaestus'2 temple at Memphis; the Greeks say among many foolish things that Psammetichus had the children reared by women whose tongues he had cut out. 3.

Herodotus on Necos (Nechos II 610–595 B.C.)

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Psammetichus had a son, Necos, who became king of Egypt. It was he who began building the canal into the Red Sea, which was finished by Darius the Persian. This is four days' voyage in length, and it was dug wide enough for two triremes to move in it rowed abreast. It is fed by the Nile, and is carried from a little above Bubastis by the Arabian town of Patumus; it issues into the Red Sea. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Digging began in the part of the Egyptian plain nearest to Arabia; the mountains that extend to Memphis (the mountains where the stone quarries are) come close to this plain; the canal is led along the foothills of these mountains in a long reach from west to east; passing then into a ravine, it bears southward out of the hill country towards the Arabian Gulf. Now the shortest and most direct passage from the northern to the southern or Red Sea is from the Casian promontory, the boundary between Egypt and Syria, to the Arabian Gulf, and this is a distance of one hundred and twenty five miles, neither more nor less; this is the most direct route, but the canal is far longer, inasmuch as it is more crooked. In Necos' reign, a hundred and twenty thousand Egyptians died digging it. Necos stopped work, stayed by a prophetic utterance that he was toiling beforehand for the barbarian. The Egyptians call all men of other languages barbarians. 159.

“Necos, then, stopped work on the canal and engaged in preparations for war; some of his ships of war were built on the northern sea, and some in the Arabian Gulf, by the Red Sea coast: the winches for landing these can still be seen. He used these ships when needed, and with his land army met and defeated the Syrians at Magdolus,66 taking the great Syrian city of Cadytis67 after the battle. He sent to Branchidae of Miletus and dedicated there to Apollo the garments in which he won these victories. Then he died after a reign of sixteen years.

Herodotus on Psammis (Psamtik II: 595–589 B.C.)

After Necos died his son Psammis reigned in his place. Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “While this Psammis was king of Egypt, he was visited by ambassadors from Elis, the Eleans boasting that they had arranged the Olympic games with all the justice and fairness in the world, and claiming that even the Egyptians, although the wisest of all men, could not do better. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

When the Eleans came to Egypt and announced why they had come, Psammis assembled the Egyptians reputed to be wisest. These assembled and learned all that the Eleans were to do regarding the games; after explaining this, the Eleans said that they had come to learn whether the Egyptians could discover any juster way. The Egyptians deliberated, and then asked the Eleans if their own citizens took part in the contests.

The Eleans answered that they did: all Greeks from Elis or elsewhere might contend. Then the Egyptians said that in establishing this rule they fell short of complete fairness: “For there is no way that you will not favor your own townsfolk in the contest and wrong the stranger; if you wish in fact to make just rules and have come to Egypt for that reason, you should admit only strangers to the contest, and not Eleans.” Such was the counsel of the Egyptians to the Eleans. 161.

Herodotus on Apries (589–570 B.C.)

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Psammis reigned over Egypt for only six years; he invaded Ethiopia, and immediately thereafter died, and Apries the son of Psammis reigned in his place. He was more fortunate than any former king (except his great-grandfather Psammetichus) during his rule of twenty-five years, during which he sent an army against Sidon and fought at sea with the king of Tyre. But when it was fated that evil should overtake him, the cause of it was something that I will now deal with briefly, and at greater length in the Libyan part of this history. Apries sent a great force against Cyrene and suffered a great defeat. The Egyptians blamed him for this and rebelled against him; for they thought that Apries had knowingly sent his men to their doom, so that after their perishing in this way he might be the more secure in his rule over the rest of the Egyptians. Bitterly angered by this, those who returned home and the friends of the slain openly revolted. 162. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Hearing of this, Apries sent Amasis to dissuade them. When Amasis came up with the Egyptians, he exhorted them to desist; but as he spoke an Egyptian came behind him and put a helmet on his head, saying it was the token of royalty. And Amasis showed that this was not displeasing to him, for after being made king by the rebel Egyptians he prepared to march against Apries. When Apries heard of it, he sent against Amasis an esteemed Egyptian named Patarbemis, one of his own court, instructing him to take the rebel alive and bring him into his presence. When Patarbemis came and summoned Amasis, Amasis (who was on horseback) rose up and farted, telling the messenger to take that back to Apries. But when in spite of this Patarbemis insisted that Amasis obey the king's summons and go to him, Amasis answered that he had long been preparing to do just that, and Apries would find him above reproach, for he would present himself, and bring others. Hearing this, Patarbemis could not mistake Amasis; he saw his preparations and hastened to depart, the more quickly to make known to the king what was going on. When Apries saw him return without Amasis, he did not stop to reflect, but in his rage and fury had Patarbemis' ears and nose cut off. The rest of the Egyptians, who were until now Apries' friends, seeing this outrage done to the man who was most prominent among them, changed sides without delay and offered themselves to Amasis. 163.

“Learning of this, too, Apries armed his guard and marched against the Egyptians; he had a bodyguard of Carians and Ionians, thirty thousand of them, and his royal palace was in the city of Saïs, a great and marvellous palace. Apries' men marched against the Egyptians, and so did Amasis' men against the foreigners. So they both came to Momemphis and were going to make trial of one another. 164.

“When Apries with his guards and Amasis with the whole force of Egyptians came to the town of Momemphis, they engaged; and though the foreigners fought well, they were vastly outnumbered, and therefore were beaten. Apries, they say, supposed that not even a god could depose him from his throne, so firmly did he think he was established; and now, defeated in battle and taken captive, he was brought to Saïs, to the royal dwelling which belonged to him once but now belonged to Amasis. There, he was kept alive for a while in the palace and well treated by Amasis. But presently the Egyptians complained that there was no justice in keeping alive one who was their own and their king's bitterest enemy; whereupon Amasis gave Apries up to them, and they strangled him and then buried him in the burial-place of his fathers. This is in the temple of Athena, very near to the sanctuary, on the left of the entrance. The people of Saïs buried within the temple precinct all kings who were natives of their district. The tomb of Amasis is farther from the sanctuary than the tomb of Apries and his ancestors; yet it, too, is within the temple court; it is a great colonnade of stone, richly adorned, the pillars made in the form of palm trees. In this colonnade are two portals, and the place where the coffin lies is within their doors. 170. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Did a Fart Lead to a Revolt Against Apries

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a fart set off a chain of events that led to a revolt against King Apries of Egypt. Iphikrates posted on Reddit.com: In 570 B.C. the Egyptian king Apries, at the urging of the Lybians whose lands were being usurped, sent a large army against the Greek settlers of Cyrene (near modern Benghazi). The Greeks, however, proved silent but deadly: contrary to everyone's expectations, the Egyptian army suffered a crushing defeat. Believing that Apries deliberately sent them out to die, the survivors banded together with the relatives of the fallen and rebelled against the king. Apries responded by sending a trusted man named Amasis to dissuade the rebels, but they instead proclaimed Amasis their true king. Amasis figured that this trumped his previous job description and decided to roll with it. He consequently prepared to march against Apries.

Undaunted by the backfiring of his plan, Apries tried again: He sent against Amasis an esteemed Egyptian named Patarbemis, one of his own court, instructing him to take the rebel alive and bring him into his presence. When Patarbemis came and summoned Amasis, Amasis, who was on horseback, rose up and farted, telling the messenger to take that back to Apries (Hdt. 2.162.3)

When Apries heard of Amasis' refusal, he blew up and had the messenger Patarbemis mutilated. This outrage so infuriated the Egyptian population that whoever was still on Apries' side now turned coat. Apries, left with no other option, gathered his personal guard and all the mercenaries money could buy, and marched out to meet Amasis in the field.

In the hot wind of the Egyptian desert, the two armies came to blows — and Apries' outnumbered forces were swiftly overwhelmed. Apries was taken prisoner by Amasis. For a while he was kept alive, but the people demanded his death, and so Amasis' men took a rope and squeezed the air out of him. You'll notice that at the time of the fabled fart, the rebellion was already well under way. Amasis passing gas was only his way of rejecting a summons to the royal court, which started a chain of events that worsened a situation that already looked pretty bleak for Apries to begin with. It seems somewhat disrespectful to blame the uprising on a fart when in fact it was triggered by the unnecessary death of thousands of Egyptians.

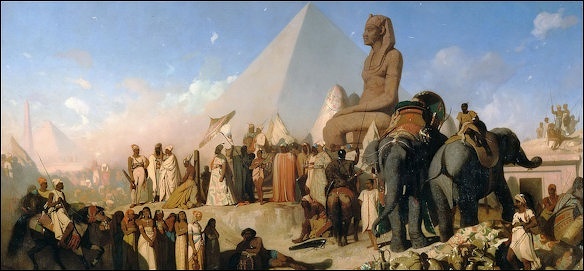

Psammetichus's meeting with Cambyses II of Persia

Herodotus on Amaris (Amasis, 570–526 B.C.)

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “After Apries was deposed, Amasis became king; he was from a town called Siuph in the district of Saïs. Now at first he was scorned and held in low regard by the Egyptians on the ground that he was a common man and of no high family; but presently he won them over by being shrewd and not arrogant. He had among his countless treasures a golden washbowl, in which he and all those who ate with him were accustomed to clean their feet. This he broke in pieces and out of it made a god's image, which he set in a most conspicuous spot in the city; and the Egyptians came frequently to this image and held it in great reverence. When Amasis learned what the townsfolk were doing, he called the Egyptians together and told them that the image had been made out of the washbowl, in which Egyptians had once vomited and urinated and cleaned their feet, but which now they greatly revered. “Now then,” he said, “I have fared like the washbowl, since if before I was a common man, still, I am your king now.” And he told them to honor and show respect for him. 173. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“The following was how he scheduled his affairs: in the morning, until the the hour when the marketplace filled, he readily conducted whatever business was brought to him; the rest of the day, he drank and joked at the expense of his companions and was idle and playful. But this displeased his friends, who admonished him thus: “O King, you do not conduct yourself well by indulging too much in vulgarity. You, a celebrated man, ought to conduct your business throughout the day, sitting on a celebrated throne; and thus the Egyptians would know that they are governed by a great man, and you would be better spoken of; as it is, what you do is by no means kingly.” But he answered them like this: “Men that have bows string them when they must use them, and unstring them when they have used them; were bows kept strung forever, they would break, and so could not be used when needed. Such, too, is the nature of man. Were one to be always at serious work and not permit oneself a bit of relaxation, he would go mad or idiotic before he knew it; I am well aware of that, and give each of the two its turn.” Such was his answer to his friends. 174.

“It is said that even when Amasis was a private man he was fond of drinking and joking and was not at all a sober man; and that when his drinking and pleasure-seeking cost him the bare necessities, he would go around stealing. Then when he contradicted those who said that he had their possessions, they would bring him to whatever place of divination was nearby, and sometimes the oracles declared him guilty and sometimes they acquitted him. When he became king, he did not take care of the shrines of the gods who had acquitted him of theft, or give them anything for maintenance, or make it his practice to sacrifice there, for he knew them to be worthless and their oracles false; but he took scrupulous care of the gods who had declared his guilt, considering them to be gods in very deed and their oracles infallible. 175.

“Amasis made a marvellous outer court for the temple of Athena71 at Saïs, far surpassing all in its height and size, and in the size and quality of the stone blocks; moreover, he set up huge images and vast man-headed sphinxes,72 and brought enormous blocks of stone besides for the building. Some of these he brought from the stone quarries of Memphis; the largest came from the city of Elephantine,73 twenty days' journey distant by river from Saïs. But what I admire most of his works is this: he brought from Elephantine a shrine made of one single block of stone; its transport took three years and two thousand men had the carriage of it, all of them pilots. This chamber is thirty-five feet long, twenty-three feet wide, thirteen feet high. These are the external dimensions of the chamber which is made of one block; its internal dimensions are: thirty-one feet long, twenty feet wide, eight feet high. It stands at the entrance of the temple; it was not dragged within (so they say) because while it was being drawn the chief builder complained aloud of the great expense of time and his loathing of the work, and Amasis taking this to heart would not let it be drawn further. Some also say that a man, one of those who heaved up the shrine, was crushed by it, and therefore it was not dragged within. 176.

“Furthermore, Amasis dedicated, besides monuments of marvellous size in all the other temples of note, the huge image that lies supine before Hephaestus' temple at Memphis; this image is seventy-five feet in length; there stand on the same base, on either side of the great image, two huge statues hewn from the same block, each of them twenty feet high. There is at Saïs another stone figure of like size, supine as is the figure at Memphis. It was Amasis, too, who built the great and most marvellous temple of Isis at Memphis. 177.

“It is said that in the reign of Amasis Egypt attained to its greatest prosperity, in respect of what the river did for the land and the land for its people: and that the number of inhabited cities in the country was twenty thousand. It was Amasis also who made the law that every Egyptian declare his means of livelihood to the ruler of his district annually, and that omitting to do so or to prove that one had a legitimate livelihood be punishable with death. Solon the Athenian got this law from Egypt and established it among his people; may they always have it, for it is a perfect law. 178.

“Amasis made friends and allies of the people of Cyrene. And he decided to marry from there, either because he had his heart set on a Greek wife, or for the sake of the Corcyreans' friendship; in any case, he married a certain Ladice, said by some to be the daughter of Battus, of Arcesilaus by others, and by others again of Critobulus, an esteemed citizen of the place. But whenever Amasis lay with her, he became unable to have intercourse, though he managed with every other woman; and when this happened repeatedly, Amasis said to the woman called Ladice, “Woman, you have cast a spell on me, and there is no way that you shall avoid perishing the most wretchedly of all women.” So Ladice, when the king did not relent at all although she denied it, vowed in her heart to Aphrodite that, if Amasis could have intercourse with her that night, since that would remedy the problem, she would send a statue to Cyrene to her. And after the prayer, immediately, Amasis did have intercourse with her. And whenever Amasis came to her thereafter, he had intercourse, and he was very fond of her after this. Ladice paid her vow to the goddess; she had an image made and sent it to Cyrene, where it stood safe until my time, facing outside the city. Cambyses, when he had conquered Egypt and learned who Ladice was, sent her away to Cyrene unharmed. 182.

“Moreover, Amasis dedicated offerings in Hellas. He gave to Cyrene a gilt image of Athena and a painted picture of himself; to Athena of Lindus, two stone images and a marvellous linen breast-plate; and to Hera in Samos, two wooden statues of himself that were still standing in my time behind the doors in the great shrine. The offerings in Samos were dedicated because of the friendship between Amasis and Polycrates,75 son of Aeaces; what he gave to Lindus was not out of friendship for anyone, but because the temple of Athena in Lindus is said to have been founded by the daughters of Danaus, when they landed there in their flight from the sons of Egyptus. Such were Amasis' offerings. Moreover, he was the first conqueror of Cyprus, which he made tributary to himself. “

Temples in the 26th Dynasty

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: During the rule of the pharaohs who hailed from Sais, the towns of the Delta became the focus of great development. The temples were restored or rebuilt; the local cults blossomed. A good indication of this remarkable apex is the clerical titulary — that is, priestly titles that either were known from earlier texts, or occur in this period for the first time. Their associated functions were often linked to a specific god, worshiped in a specific temple. The Theban region was mostly under the direct influence of the divine adoratrices, whose power had been established since the early Third Intermediate Period. Their names, inscribed on monuments, are given the same status as that of the kings who installed them in office. The office disappeared at the end of the 26th Dynasty. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Given the poor preservation of most of the Delta sites, we often have only the temple foundations and certain stone elements remaining, while the temple superstructures have completely disappeared. The temple of Amun at Tell el-Balamun/Sema-Behedet was completely renovated under Psammetichus I. The ongoing excavations at Buto give us a basic idea of the temple of Wadjit, built by Amasis. The same is true for the temples of Sais, although excavations have revealed very few remains in situ. At Mendes, Amasis rebuilt the temple of Banebdjed. Of the four monumental monolithic naoi, dedicated to Shu, Geb, Ra, and Osiris — the four “bas” of Banebdjed — only one is standing today, dominating an open field. At Tanis the discovery of foundation deposits bearing the name of Apries indicates the period in which the Mut temple was renovated and embellished with a columned court fronting the temple. Similar renovations were carried out in the time of Apries of the temples of Amun and Amun of Ipet. In this period there were also building activities in Imet (Tell Nabasha/Tell Faraun) and Pithom (Tell el-Maskhuta), where Ramesside monuments from Tell el-Rataba in the Wadi Tumilat were re-used. In Memphis the building activities concentrated on a restoration of the Serapeum and the construction of the palace of Apries. The many stelae dedicated to the deceased Apis date to this period.

“The northern section of the temple complex there, several chapels were dedicated to specific forms of Osiris, such as “Osiris Wennefer, “Neb Djefau”” (Osiris Wennefer, Lord of Nourishment) and “Osiris Hery-ib pa Ished” (Osiris Who Resides in the Persea Tree). The buildings are inscribed with the names of the contemporary ruling pharaohs and divine adoratrices. The latter also erected several chapels in the Montu temple complex in north Karnak, while their funerary chapels were located within the walls of Medinet Habu. To the south, at El- Kab, a temple of Psammetichus I has been brought to light, and several other temples in Upper Egypt were embellished in this period.

“Remains of several 26th-Dynasty temples in the oases indicate important cult activities in the Libyan Desert. At Siwa the Egyptian-style temple of Aghurmi was dedicated to the form of Amun popular in the oasis: the god depicted with the head of a ram. This temple was built at the time of Amasis and is the only 26th-Dynasty construction of which more than the foundations remain. The name of Amasis is also found on several chapels in Ain Muftella in the Bahariya Oasis. These chapels were part of a carefully designed decorative program, displaying an elaborate pantheon, “artistry and epigraphy, with a sophistication that is typical for this period of archaizing workmanship. Many temples are embellished in this period with naoi of hard stone, such as granite or greywacke.

Typical also is the widespread use of Egyptian “bekhen” stone. Two good examples are the naos of Mefky, dedicated to a local form of Osiris and dated to the rule of Amasis, and the naos of Baqlieh, dedicated to Thoth “who separates the two companions”. The temple courts housed an abundance of statues of priests who lived during the 26th Dynasty, or slightly later, such as Neshor, Wedjahorresne, and Horkhebi. These statues typically have an autobiographical text inscribed on their back pillar. The inscriptions provide us with a record of the existence of temples for which we have no other evidence and they contain information on temple function and decoration for which we have no other sources.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions”edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024