Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids) / Death and Mummies

OLD KINGDOM TOMBS

In late 2018, archaeologists announced the discovery of an untouched and well-preserved 4,400-year-old tomb of a royal priest — Wahtye — and his family. The “one of a kind” find, in Saqqara (See Below). A documentary, directed by James Tovell, highlighting the 3,000 artifacts discovered within including the first complete mummified lion cub and a temple dedicated to the Egyptian cat goddess Bastet. According to Yahoo News: There's also evidence that the family died from an epidemic, which was probably malaria — and, if proven, it would be the first documented case of malaria in history. The owner of the tomb, which was buried 16 feet beneath the sand, has an interesting story too, having served King Neferirkare of the Old Kingdom’s fifth dynasty, which ruled from around 2500 to 2350 B.C. Hieroglyphs carved into the stone above the tomb’s door reveal some of his titles, including royal purification priest, royal supervisor and inspector of the sacred boat. [Source: Suzy Byrne Yahoo News, October 28, 2020] —

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In the Old Kingdom, in the third millennium B.C. the elites appear to have favored private family spaces such as the priest Wahtye’s rock-cut tomb, which included an ornate, above-ground chapel for visitors lined with painted reliefs, inscriptions and statues of Wahtye himself. Burial shafts dug into the floor of such tombs were dedicated to particular family members. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, August 2021]

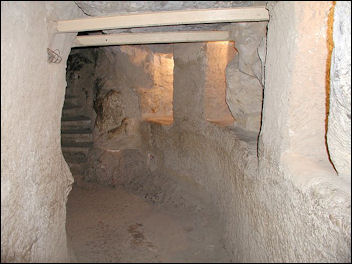

In 2020, Archaeology magazine reported: During investigation of the funerary complex of the 5th Dynasty pharaoh Djedkare Isesi (r. ca. 2381–2353 B.C.), a team from the Czech Institute of Egyptology discovered the painted tomb of a high-ranking Old Kingdom Egyptian dignitary. After descending a narrow subterranean tunnel that opened up into a series of rooms, members of the team, led by archaeologist Mohamed Megahed, found hieroglyphs on the walls announcing that a man named Khuwy was entombed within the chamber. The writing also enumerates Khuwy’s many titles, including “Secretary of the King,” “Companion of the Royal House,” and “Overseer of the Tenants of the Great House.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, January-February 2020]

“Alongside the hieroglyphs are scenes painted in colors that remain vibrant even after 4,300 years. One of the main panels depicts Khuwy himself, seated before a table piled high with food, drinks, and other offerings meant to sustain him in the afterlife. “Scenes of the tomb owner are highly unusual in Old Kingdom tombs,” says Megahed. The high-quality paintings, the tomb’s proximity to Djedkare’s own pyramid, and its design — which mimics that of a tomb belonging to a 5th Dynasty pharaoh — all suggest that Khuwy played a prominent role in the royal court.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs” by Philip J. Watson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Early Burial Customs in Northern Egypt (BAR International)

by Joanna Debowska-Ludwin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cultural Expression in the Old Kingdom Elite Tomb” by Sasha Verma (2014) Amazon.com;

“Journey to the West: The World of the Old Kingdom Tombs” by Miroslav Bárta (2012) Amazon.com;

“Saqqara: The Royal Cemetery of Memphis: Excavations and Discoveries Since 1850"

by Jean Philippe Lauer (1976) Amazon.com;

“Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2020" by Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Old and Middle Kingdom Theban Tombs” by Rasha Soliman (2009)

Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pyramids” by Mark Lehner (1997) Amazon.com;

“Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History” by Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Tomb in Ancient Egypt” by Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Tombs: The Culture of Life and Death” by Steven Snape (2011) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

Mastabas

Balat mastaba tomb Mastabas are tombs used by early dynasties. onstructed of mudbricks or limestone, they generally had a flat-roof, rectangular shape and inward sloping sides.

Mastabas are named after the Arabic word for “rectangular mud benches.” From a distance, a flat-topped mastabas do resemble benches. Historians speculate that the Egyptians may have borrowed architectural ideas from Mesopotamia, since at the time they were both building similar structures.

Some mastabas were built to resemble pyramid. They often had ramps that were reminiscent of the causeways that led from the Nile Valley to the pyramids on the high plateau and had attached but separate rooms where pottery and statues were kept. The deceased were often laid to rest in burial shafts.

Old Kingdom tombs were held up with cedars from Lebanon. The pharaoh's sarcophagi were chiseled out of southern Egypti granite and floated 500 miles down the Nile from Aswan. Archaeologists found an ancient tunnel connecting two 4,000 year-old tombs to the tomb pharaoh Amenemhet I in Saqqara, Egypt. Scientists believe that the tunnels were created social-climbing Egyptian noblemen wanted to tap into the afterlife of the Pharaoh. Archaeologist Dr. David Silverman told AP: "Not only did they apparently feel thy were worthy, but they wanted to ensure they would have the best possible afterlife they could.

Saqqara

Saqqara (32 kilometers, 20 miles south of Cairo) is the home of ancient Egypt's oldest cemetery and was a religious center for the ancient capital of Memphis. Built on top of plateau that overlooks Memphis, it is famous for its mastabas (tombs) and step pyramids (the oldest large building in the world). Most of the buildings were built between 3,100 and 2181 B.C. The most famous of these is the Step Pyramid of Zoser, built in Third Dynasty of Old Kingdom for a pharaoh named Zoser (Djoser). It is possible to ride by camel from the Great Pyramids of Giza to Saqqara. This route passes by the pyramids of Abu Sir and Abu Gaurab that are otherwise difficult to reach.

Saqqara sits on the top or a barren, rocky escarpment above the green Nile Valley. It was established as a burial ground for Memphis. The cemetery area was huge. It stretched for 45 miles along the Nile. There was an entire cemetery devoted to mummified cats. Tombs found at Saqqara span a lengthy period of time. The area on the eastern escarpment of the North Saqqara plateau contains tombs dating back to the Second Dynasty, about 4,800 years ago, tombs dating to the 18th Dynasty (circa 1550 to 1295 B.C), the Late Period (circa 712 to 332 B.C.), as well as more tombs and artifacts dating to Ptolemaic and Roman times.

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: On the Nile's west bank, where riverfed crop fields give way to desert, the ancient site of Saqqara is marked by crumbling pyramids that emerge from the sand like dragon's teeth. Most striking is the famous Step Pyramid, built in the 27th century B.C. by Djoser, the Old Kingdom pharaoh who launched the tradition of constructing pyramids as monumental royal tombs. More than a dozen other pyramids are scattered along the five-mile strip of land, which is also dotted with the remains of temples, tombs and walkways that, together, span the entire history of ancient Egypt. But beneath the ground is far more — a vast and extraordinary netherworld of treasures. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, August 2021]

Apart from its eroding pyramids, Saqqara was known, by contrast, for its subterranean caverns, which locals raided for mummies to use as fertilizer and tourists ransacked for souvenirs. Looters carted off not only mummified people but also mummified animals — hawks, ibises, baboons. Saqqara didn’t attract much archaeological attention until the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, who became the first director of Egypt’s Antiquities Service, visited in 1850. He declared the site “a spectacle of utter devastation,” with yawning pits and dismantled brick walls where the sand was mixed with mummy wrappings and bones. But he also noticed the half-buried statue of a sphinx, and probing further he found a sphinx-lined avenue leading to a temple called the Serapeum. Beneath the temple were tunnels that held the coffins of Apis bulls, worshiped as incarnations of Ptah and Osiris.

mastaba tomb, one of the oldest kinds

Why was Saqqara Such an Important Burial Place for Ancient Egyptians?

"The reasons for being buried at the site differed through time," Nico Staring, an Egyptologist and guest researcher at Leiden University, told Live Science. One of the most important reasons was its nearness to Memphis. "Saqqara was the main necropolis associated with the capital city of Memphis, which remained, to a large extent, an administrative center throughout Egypt's history as well as being a major religious center celebrating the cults of a variety of deities" Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, told Live Science. "Saqqara should be viewed as a component of the wider, lived urban environment" he said. "The living inhabitants of Memphis shaped and reshaped the necropolis over many generations, and so the life histories of both the city and its necropolis were closely intertwined." [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 2, 2024]

Saqqara was also revered because some early Egyptian pharaohs built their tombs there. During the second dynasty (circa roughly 2800 to 2650 B.C.) the pharaohs Hotepsekhemwy, Reneb and Ninetjer all constructed tombs at the site, Lara Weiss, CEO of the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Germany, told Live Science. The third dynasty pharaoh Djoser famously constructed a step pyramid at Saqqara, and several other pharaohs, such as the fifth dynasty pharaohs Userkaf, Unas and Djedkare Isesi, also built pyramids at the site. As the pharaohs were buried, "large numbers of their court officials constructed their so-called mastaba tombs in their vicinity," Staring added, explaining that the grounds weren't just for royalty.

Even in the New Kingdom (circa 1550 to 1070 B.C.), a time when pharaohs were buried in the Valley of the Kings about 300 miles (483 kilometers) away, many officials still wanted to be buried at Saqqara. This happened because of the site's history and association with Egyptian deities, Staring said. While "the kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes, the kingdom's most important administrators built their temple-shaped tombs at Saqqara, at a site that was imbued with history and a site that was considered to be the abode of various prominent deities such as Sokar, a god of death," Staring said.

On why Saqqara was a popular burial place for 3,000 years, Campbell Price, of the Manchester Museum, told Smithsonian magazine the answer also has to do with Saqqara’s pyramids. The necropolis had always been a center for religious cults, from the time high-ranking Egyptians were first buried there, often in low, flat-roofed tombs called mastabas, and probably long before. To help bring the country together after turbulent times, the 7th century B.C. Egyptian ruler Psamtik encouraged a revival of traditional rituals and belief; after a long period as a backwater, Saqqara exploded again in popularity. Far more than a local cemetery, says Price, it became a pilgrimage site, “like an ancient Mecca or Lourdes,” attracting visitors not just from Egypt but from all over the eastern Mediterranean. Buildings such as the Step Pyramid were already thousands of years old at this time, and people believed their creators, such as Djoser and his architect Imhotep, were gods themselves. Cults and temples sprang up. Pilgrims would bring offerings, and they vied for burial spaces for themselves and their families near the ancient, sacred tombs. “Saqqara would have been the place to be seen dead in,” says Price. “It had this numinous, divine energy that would help you get into the afterlife.” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, August 2021]

That created conditions for a thriving commercial operation entwined with the spiritual one, resulting in a kind of real estate market for the dead. “It’s a business,” says Dodson. There was probably a sliding scale of options available. Senior officials and military officers were interred in large tombs near the Old Kingdom pyramids of Unas and Userkaf, for example, while the poorest in society were probably buried “in the desert in a sheet.” But the wealthy middle classes appear to have opted for a shared shaft, perhaps with a private niche if they could afford it, or were simply piled with others on the floor. If you wanted to be close to the magical energy of Saqqara’s gods and festivals, Dodson says, “you bought yourself a space in a shaft.” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, August 2021]

The supersized burials unearthed found at Saqqara reveal how intense the desire for particular locations became — and how profitable they were. Instead of digging new tombs, the priests in charge of burials reused older shafts, expanding them and, Price and Dodson suggest, cramming in as many coffins as they could. The cliffs of the Bubasteion, overlooking the landscape and close to the main processional route, may have been one of the most sought-after spots of all.

Mastabas of Saqqara

Many of the tombs in Saqqara are mastabas, which have been built above the ground. Many were built for prominent Old Kingdom noblemen, officials and bureaucrats in an area also known as the Necropolis of Memphis. The tomb walls bear inscriptions showing scenes of everyday life in ancient Egyptian farming, animal breeding, hunting as well as religious rites and the offering of sacrifices to the dead.

The Mastaba of Ptah-Hotep to the southwest of the Step-Pyramid contains numerous paintings and inscription, the most famous of which shows the ancient Egyptian philosopher Ptah-Hotep being entertained by a band of musicians. The Mastabas of Kagemni has mural reliefs with bird hunting scenes and the mastaba of Mereruka has inscriptions showing farming, hunting, craft making and veterinarians treating animals.

Excavations here have found the remains of officials in charge or medicine, gold and silver, housekeeping tools, canals and granaries. One inscription shows a teacher scolding a child for drinking beer instead of doing his homework. Another shows a teacher encouraging students to become scribes to avoid an adult life of labor and toil. Officials brag about the number of Nubian serfs at their disposal. Lovers express their feeling. One inscription reads: "He is like a datecake dipped in beer."

Burial Chamber in the Pyramid of Cheops

Cheops interior The 30-foot-high burial chamber in the Pyramid of Cheops is about halfway between the base and the summit. The 150-foot tunnel leading to the chamber is only four feet high, which means that people that enter it have to bend over to reach the chamber. Inside the King's chamber is a huge granite sarcophagus that is an inch wider than the entrance to prevent its removal. The lid which is slightly smaller than the entrance has been removed. To keep the dead Pharaoh cool the pyramid is even outfit with air vents.

The burial chamber in the Pyramid of Cheops is topped by five granite slabs and a pitched roof to prevent it from being crushed by the weight of the pyramid. Nearby is a chamber of unknown purpose originally thought to have been the queen's chamber. Exiting from both chambers are several narrow shafts that may have been built for the pharaoh's spirit to come and go.

The chamber was sealed from within by workers who exited through a tunnel that led to a subterranean shaft. Underneath the base is a chamber carved out of bedrock that may have been the original royal burial site. In spite of hidden entrances, granite plugs and walled-off passages, built in part to foil thieves, the pharaohs treasures were looted, most likely by fellow ancient Egyptians.

Tomb Texts from the Old Kingdom

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “Documents written on papyri were found in some pyramid temples, especially at Abusir. They concern such matters as lists of priests on duty, records of offerings brought to the temple, accounts, inventories of temple equipment and passes authorizing access to the temple. Several settlements of priests, and of craftsmen and artists, involved in the running of pyramid temples, have been located, in particular at Giza. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Representations carved on the walls of tombs include scenes of everyday life on the owner's estates and so show how even ordinary people lived and worked. We must be rather careful when interpreting these scenes and must not take them entirely at face value. They were included in order to play a role in the tomb owner's afterlife, not as an accurate record. |::|

“Sometimes, especially in the later part of the Old Kingdom, the tombs contained biographical texts. Many are just self-praising but others are real records of the tomb owner's achievements. This is how one of them, an official called Weni, described a mission assigned to him by King Merenre of the Sixth Dynasty: 'His Majesty sent me to Hatnub in order to bring a great altar of travertine of Hatnub. I brought this altar down for him in 17 days. After it had been quarried at Hatnub, I had it transported downstream in the barge that I had made for it, a barge of acacia wood of 60 cubits in length and 30 cubits in width. It was built in 17 days and in the third month of summer, when there was no water on sandbanks, it was safely moored at the pyramid of King Merenre.'” |::|

Pyramids as Mortuary Temples for the Pharaohs

According to PBS: “Each pyramid has a mortuary temple and a valley temple linked by long causeways that were roofed and walled. Alongside Khufu and Khafre's pyramids were large boat-shaped pits and buried boats that were presumably meant to aid the pharaoh's journey to the afterlife.... In addition, cemeteries of royal attendants and relatives surround the three pyramids. The entire plateau is dotted with these tombs, called mastabas, which were built in rectangular bench-like shapes above deep burial shafts.”

The pyramid were manifestations of the Egyptians' beliefs in the afterlife..Early pre-pyramid royal tombs were essentially made up of an underground burial complex in one location-with a large rectangular enclosure a kilometer or so away, where ceremonies for the dead were carried out. The first pyramid, Djoser’s Step Pyramid, which in many ways combined the old separate elements in one location. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Bristol, where he teaches Egyptology, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

The pyramid were manifestations of the Egyptians' beliefs in the afterlife..Early pre-pyramid royal tombs were essentially made up of an underground burial complex in one location-with a large rectangular enclosure a kilometer or so away, where ceremonies for the dead were carried out. The first pyramid, Djoser’s Step Pyramid, which in many ways combined the old separate elements in one location. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Bristol, where he teaches Egyptology, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Dr Aidan Dodson wrote for BBC: It is important to realise that the actual pyramid was only one part of the overall magical machine that transferred the dead king between the two worlds of the living and the dead. The pyramid complex began on the edge of the desert, where the Valley Building-now lost under a Cairo suburb-formed a monumental portal. |::|

“From here, the burial cortege, priests and visitors would pass through ceremonial halls onto a causeway that ascended the desert escarpment to the mortuary temple, built against the east face of the pyramid. Here, behind a great colonnaded courtyard, lay the sanctuary in which offerings were made to the king's spirit. Either side of the mortuary temple lay a buried boat-perhaps a souvenir of a funeral flotilla, or put there to allow the king to voyage in the heavens-and to the south was a miniature pyramid. Such so-called subsidiary pyramids are of uncertain purpose: they are generally classified as 'ritual'-archaeologists' code for 'obviously important to the ancient people, but we have absolutely no idea why'. |::| “An offering place was one of the two immutable parts of an Egyptian tomb. The other was the burial place. In the Great Pyramid-and in most other pyramids-this was reached from a narrow, low, opening in the north face. The interior of the Great Pyramid is complex, almost certainly resulting from a number of changes of plan. |::|

“The Great Pyramid was the hub of a huge complex of cemeteries intended for members of the royal court. To the east, three of the king's wives had their own small pyramids, with streets of mastaba-bench-shaped tombs-for his sons and daughters. West of Khufu's pyramid was an even larger cemetery for the great officials of state. All these tombs had been laid out to a single design, a unified architectural conception of the king surrounded by his court, in death as in life. It is a concept that has been without direct parallel before or since.” |::|

Private Tombs North Near Senusret III Pyramid Complex in Dahshur

Dieter Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In ancient Egypt, while a royal pyramid was under construction, the area adjoining it could not be used for private tomb building. Royal courtiers had to build their tombs either at a safe distance from the construction area or near the pyramid of the preceding king. The officials of Senusret III erected their tombs in a close group that was separated from the royal pyramid complex by a narrow desert strip. This cemetery was still in use during the reign of King Amenemhat III (r. ca. 1859–1813 B.C.), Senusret III's successor and presumed son. In 1894, The Step Pyramid of Djoser was particularly well regarded long after it was built. "Interestingly, old monuments from the past continued to exert influence on later generations," Staring said. Even when it was 1,000 years old, the Step Pyramid complex "received literate visitors that perpetuated their admiration for the monument in graffiti written on the walls of the complex." Staring said.

Although it is an ancient place, Saqqara is still an active burial site today. "Saqqara continues to be used as a burial ground, albeit to a much lesser extent, into the present," Ikram said. The importance of Saqqara "diminished dramatically" as Christianity became the main religion in Egypt during the fourth and fifth centuries, Ikram noted. But even with the decline of Egypt's polytheistic religion, Saqqara still saw some use — for example, the Coptic Monastery of Jeremiah was built at the site in the fifth century, Weiss noted.

Jacques de Morgan (1857–1924) excavated about thirty tombs, which represents approximately half of the cemetery. Many tombs consisted only of a shaft with a burial chamber. Several were brick mastabas of moderate dimensions, but a few tombs were monumental and cased with fine quality limestone. Almost all above-ground buildings were destroyed in antiquity, leaving only foundations and a few brick or stone courses; with very few exceptions, all underground burial chambers were robbed. [Source: Dieter Arnold. Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“One task of the archaeologist is to reconstruct the original appearance of the architecture from the remains left by the stone robbers. Several of the mastabas were inscribed with the names and titles of the tomb owner and occasionally biographical information about his or her life. Because of the historical value of these texts, the tiniest fragments must be recorded and studied. The expedition of the Metropolitan Museum has been systematically reexcavating the cemetery since 1995. The major mastaba tombs belonging to the officials Nebit, Horkherty, and Khnumhotep have been explored and recorded. \^/

“The mastabas of Nebit and Horkherty had smooth, gently sloping walls that were articulated in the east with two niches containing false doors and relief scenes of offering rituals. Both mastabas measured 10.5 x 21 meters and were 4.5 meters high. Large inscriptions ran along the tops of the walls and down the corners. Almost the entire north wall of Nebit's mastaba is preserved, along with a section of the north end of the east wall. The inscriptions include the cartouches of Senusret III, indicating that Nebit served under that king. They also reveal that Nebit held the offices of vizier and overseer of the pyramid city. Horkherty's less well preserved inscriptions include a number of religious titles. \^/ “The mastaba of Khnumhotep had a different, dramatic surface articulation consisting of paneled walls structured by an elaborate system of projections and recesses. This type of building design and decoration plays a long and important role in Egyptian architecture and its origins extend back to Early Dynastic palace architecture. A beautiful detail was the representation of bundles of papyrus blossoms in windowlike panels. On Khnumhotep's mastaba, long inscriptions framed the top of the building and the panels of the four false doors on the east side. These fragmentary inscriptions include important information about military campaigns that Khnumhotep appears to have undertaken in the Levant. \^/

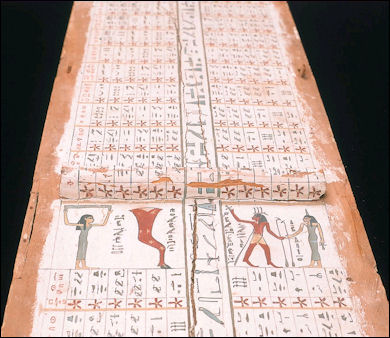

“The underground tombs consisted of monumental, stone-lined chambers, where the bodies of the tomb owners were laid to rest in wood coffins nested inside stone sarcophagi. A wall niche enclosed the canopic chest, which contained some of the deceased's internal organs. The crypts of Nebit, Horkherty, and Khnumhotep were found completely robbed, but the burial of Horkherty's wife Sitwerut was discovered untouched. The meticulous recording of her burial has enabled the excavators to reconstruct the funerary equipment of an upper-class Dynasty 12 lady. Sitwerut was buried in her own stone sarcophagus that contained a rectangular cedar wood coffin with gilded edges. Her mummy was wrapped in linen and her body placed in a gilded, mummy-shaped inner coffin. Her jewelry was composed of faience and carnelian beads, and had elements made of wood covered with gold foil and decorated cartonnage, indicating that the objects were made specifically for her burial. Among her adornments were bracelets, anklets, a girdle, and a broad collar. The four alabaster jars of her canopic burial had human heads, and one even preserved some of the ancient embalming fluid.” \^/

Ancient Egyptian Tombs of Commoners

Chephren Cemetery seen from the Second Pyramid Commoners generally weren't mummified or were only slightly mummified. Mummification was mostly reserved for royalty and nobility. Most were buried with and few or no grave goods in the fetal position in simple shrouds or jars with the top of the skull aligned toward the north and the face pointing east towards the rising sun. Wooden coffins were too expensive for most commoners. Many were buried in the sand on placed in a hole.

Some had tombs. The tombs of the pyramid builders consisted of vaulted chambers with small gabled openings. The tombs came in a variety of forms: stepped domes, beehives, gabled roofs, simplified pyramids (some even had ramps, which may have represented ramps used to build the real pyramids). Hawass found one tomb with an "egg-dome" (a mud brick outer dome with an egg-shaped corbeled vault) built over a rectangular pit.

Some of the tombs of the pyramid builders had false doors, crude hieroglyphics and multiple chambers, one for each family members, and courtyards with granite and diorite walls. This shows that their tombs had some features previously only associated with the tombs of nobility — but in cases they were made from mud brick rather stone. At the upper part of the cemetery for the pyramid builders were the people with the highest status. They had titles like "director of the draftsmen," overseer of the masonry," “director of workers,” and "inspector of the craftsmen."

Often multiple burials were found in a single grave. Often two adults and one or two children were buried together, or several children were buried with a single adult. In 1991, children and infants were found in Abyos buried under a house dated to the to around 2000 B.C. Three were newborns interred in pots. A fourth was found lying under a bowl on top of a toddler.

Tombs of commoners often provide important information for archaeologists because they have usually been undisturbed by grave robbers who know they would be unlikely to find anything of value inside.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024