Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids)

EARLIEST DYNASTIES OF ANCIENT EGYPT

skeleton in the remains of a basketwork coffin, about 3000 BC

According to Live Science: Dynasties one and two date back around 5,000 years and are often called the "Early Dynastic" or "Archaic" period. The first pharaoh of the first dynasty was a ruler named Menes (or Narmer, as he is called in Greek). He lived over 5,000 years ago, and while ancient writers sometimes credited him as being the first pharaoh of a united Egypt, however archaeological research suggests that this is not true. Recently found inscriptions tell of rulers — such as Djer and Iry-Hor — who appear to have ruled earlier and other finds have been made which suggest that there were pharaohs before Menes who ruled a united Egypt. Scholars sometimes refer to these pre-Menes rulers as being part of a "dynasty zero." [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

According to New Catholic Encyclopedia: “Protodynastic and Early Dynastic Period (c. 3200–2575 B.C.). Modern scholars refer to the period of c. 3200 to 3000 B.C. as the Protodynastic Period because during these years, early rulers expanded their power and formed a unified Egyptian state. Some of these rulers are known by name from works of art, such as a ceremonial palette representing king Narmer. Narmer, who came from Upper Egypt, is generally credited with joining the north and south into one nation. On his palette, Narmer is shown defeating enemies associated with the Delta. The king was central to Egyptian religious and political thought because he was responsible for ensuring that ma’at, or cosmic order and justice, was maintained. As the palette of Narmer shows, even at this early stage in Egyptian history, artists had adopted a canon, or style, of representation which would remain typical of all Egyptian art. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

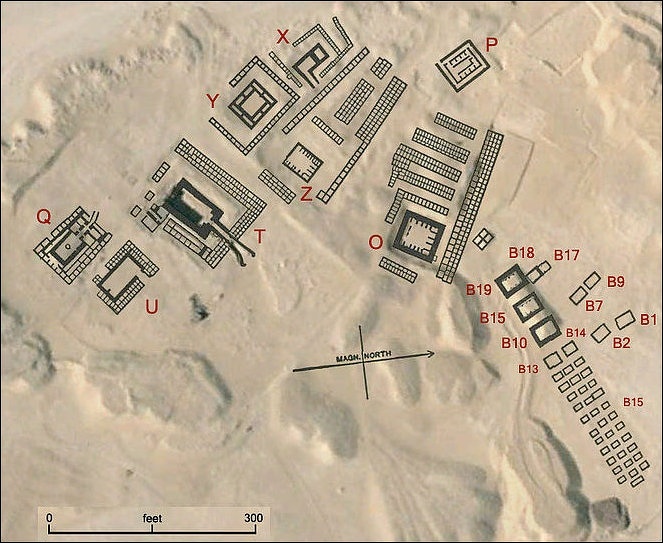

“The sequence of numbered dynasties recorded by Manetho begins after the initial unification of Egypt. The first three dynasties (c. 3000–2575 B.C.) comprise the Early Dynastic Period, during which the kings strengthened the structure of Egyptian government. In the Third Dynasty (c. 2650 B.C.) Egypt reached an important point under the reign of Djoser, who built the first large-scale stone monument for his funerary complex at Saqqara, the cemetery of Memphis (biblical Noph). The center of the complex was a structure of seven graduated layers, the so-called Step Pyramid. Djoser was buried in chambers beneath the pyramid, and buildings around it provided a spiritual 'home' for the dead king where religious rituals ensured his eternal life.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2: From the Great Pyramid to the Fall of the Middle Kingdom” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Early Dynastic Egypt” by Toby A.H. Wilkinson (2001) Amazon.com;

"In the Shadow of the Pyramids: Egypt during the Old Kingdom" by Jaromir Malek, Many illustrations (1986) Amazon.com;

”Ancient Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization” by Douglas J. Brewer (2005) Amazon.com;

“Analyzing Collapse: The Rise and Fall of the Old Kingdom” by Miroslav Bárta , Aidan Dodson, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume I: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

"Towards a New History for the Egyptian Old Kingdom – Perspectives on the Pyramid Age" by Peter Der Manuelian (Author) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Descendants of a Lesser God: Regional Power in Old and Middle Kingdom Egypt”

by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano (2023) Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

"Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms" by Miriam Lichtheim and Antonio Lopriano (2006) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“When the Pyramids Were Built: Egyptian Art of the Old Kingdom” by Dorothea Arnold (1999) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids” by The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1999) Amazon.com;

"Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean During the Old Kingdom: an Archaeological Perspective" by Karin N. Sowada and Peter Grave (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

First Dynasty 3100 – 2686 B.C.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The unification of Egypt began with the First Dynasty. It also marked the beginning of Egyptian history, for it was the time when hieroglyphic writing in Egypt became standardized. Little is known about the First or Second Dynasty due to the ravages of wars and of time. Many of the comments regarding the early Pre-dynastic Periods can be used for both the first dynasty and the second. Architecture of the First Dynasty evolved from simple structures of wood, reeds and mud, to larger, more complicated buildings of brick and later of stone. During the First Dynasty, the traditions of wood structures had a strong influence on the later buildings constructed of brick and stone. Mat and reed textures are imitated on many stone walls giving a distinctly Egyptian character to the architecture. In addition, Egyptian sculpture was quite distinct and elaborate. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

On the 1st Dynasty, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “Egypt was unified around 3000 B.C., when the kings of the south of the country absorbed their northern neighbours into a single state, with a newly-founded capital in the north, at Memphis (about 20km-12 miles-south of modern Cairo). It was after this event, during the first two dynasties, that the ground-rules of Egyptian society were laid and the hieroglyphic script developed. The kings of the 1st Dynasty were buried in the heart of the old southern kingdom, at Abydos, in brick-lined tombs out in the desert, with an offering place flanked by stelae bearing their names. Perhaps the finest is the one shown here, of King Djet. This was found in 1898, and is now in the Louvre in Paris.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Scientists have found the stelae of a 1st dynasty queen and tags made of bone, including some with some of the oldest writing known, dating to about 3200 B.C. Mud brick and plaster graves in a sort of boat graveyard yielded 5,000-year-old planked boats— the oldest ever found. It is believed these boats were meant to transport supplies to the next world, allowing the king to tour his realm in death as he did while he was alive. Fourteen vessels, some over 20 meters in length, were found.

First Dynasty Rulers

According to folk tales, Menes (also thought to be Narmer became the first mortal king after the gods united Upper and Lower Egypt. By the end of the first dynasty there appears to have been rival claimants for the throne. The rulers of the First Dynasty were Narmer, Aha, Djer, Djet, Den, Anedjib, Semerkhet and Qaa. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

King Aha was the first ruler of the first dynasty. His name was found on wine stoppers and part of a jar. Next to his grave an elite woman was buried in a wooden coffin along with five other courtiers. They may have been human sacrifices. John Galvin wrote in National Geographic, “King Aha, "The Fighter," was not killed while unifying the Nile's two warring kingdoms, nor while building the capital of Memphis. No, one legend has it that the first ruler of a united Egypt was killed in a hunting accident after a reign of 62 years, unceremoniously trampled to death by a rampaging hippopotamus. News of his demise brought a separate, special terror to his staff. For many, the honor of serving the king in life would lead to the more dubious distinction of serving the king in death. John Galvin, National Geographic, April 2005 +++]

During the early dynasties, every king planning to be buried at Abydos erected a ceremonial enclosure near the Nile’s flood plain and a tomb to the west — the realm of the dead — after ritually destroying the enclosure of his predecessor. A jackal god watched over the necropolis. Over time he merged with Osiris, god of the dead. People believed that Osiris was interred at Abydos, which became a pilgrimage site where kings built temples and cenotaphs.

Second Dynasty 2890 – 2686 B.C.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The Second Dynasty, maintained the war records of raids into Nubia. None of the raid efforts were large scale or resulted in permanent conquest, but they are indicative of a desire for the wealth of Nubia. Another large exploit of the Egyptians during the Second Dynasty is the shift of a power center from Abydos to Memphis. This shift, due largely in part to resources, could also possibly have been due to the cult of the Sun god Ra beginning during this period, and also due to a want for greater political control by the king. By the end of the 2nd Dynasty an end to political opposition of north and south established a basic economic, religious and political system, which lasted well into dynasties to come, and paved the way for the more affluent Third Dynasty. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

According to Archaeology magazine: The pharaohs of the 1st Dynasty were buried in tombs in the necropolis of Abydos along with hundreds of sacrificial burials. But the practice of killing great numbers of citizens evidently became a burden on society, and the 2nd Dynasty pharaohs were buried along with fewer and fewer people. By the dynasty’s end, the number of sacrificial victims accompanying their rulers to the underworld had dwindled to zero. It may have been that in the face of popular resistance, the pharaohs curtailed the practice. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

“At the end of the 1st dynasty there appears to have been rival claimants for the throne. The successful claimant’s Horus name, Hetepsekhemwy, translates as “peaceful in respect of the two powers” this may be a reference to the opposing gods Horus and Seth, or an understanding reached between two rival factions. But the political rivalry was never fully resolved and in time the situation worsened into conflict.

The rulers of the Second Dynasty were Hetepsekhemwy, Raneb, Nynetjer, Peribsen, Khasekhem (Khasekhemwy). The fourth pharaoh, Peribsen, took the title of Seth instead of Horus and the last ruler of the dynasty, Khasekhemwy, took both titles. A Horus/Seth name meaning “arising in respect of the two powers,” and “the two lords are at peace in him.” Towards the end of this dynasty, however, there seems to have been more disorder and possibly civil war.

Second and Third Dynasties (2800-2600 B.C.): When Ancient Egypt As We Know It Takes Shape?

heads of foriegners at the base of a royal statue

The Third Dynasty dynasty was one of the landmarks of Egyptian history, the time during which sun-worship, a new form of religion that later became the religion of the upper classes, was introduced. At the same time mummification and the building of stone monuments began. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Toby Wilkinson of Cambridge University wrote:“The 2nd-3rd dynasties span the end of the formative phase of ancient Egyptian civilization and the dawn of the Pyramid Age, and are crucial for our understanding of the early development of Pharaonic government, society, religion, and material culture in their classic forms. Yet the 2nd-3rd dynasties remain among the most obscure periods of ancient Egyptian history. This is largely the result of a dearth of contemporary texts, and—with the exception of royal funerary monuments—a paucity of archaeological evidence that can be securely dated to the period. By contrast, the preceding 1st Dynasty is relatively well attested, and is thus better known. There is a considerable degree of continuity in political, economic, and cultural matters between the 2nd and the 3rd dynasties, which makes it appropriate to consider the two dynasties together, despite the fact that some scholars place the 3rd Dynasty in the Old Kingdom, creating a somewhat artificial division with the preceding Early Dynastic Period (i.e., the 1st- 2nd or 1st-3rd dynasties). [Source: Toby Wilkinson, Cambridge University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“The broad historical outline of the 2nd-3rd dynasties has been established with some certainty. The 2nd Dynasty (c. 2800 – 2670 B.C.) began with a line of three kings buried at Saqqara—Hetepsekhemwy, Raneb, and Ninetjer—who are attested predominantly from sites in the Memphite region. At the end of the dynasty, the focus of royal activity seems to have switched to Upper Egypt, to judge from the surviving funerary monuments of the last two kings, Sekhemib/Peribsen and Khasekhem(wy), both of whom were interred at Abydos. Between these two groups of rulers, internal political developments and the precise sequence of kings remain uncertain. Inscriptions from the Step Pyramid complex of Netjerykhet (better known to posterity as Djoser) name five ephemeral rulers—Ba, Sneferka, Weneg, Sened, and Nubnefer—who, on archaeological and epigraphic grounds, can plausibly be dated to the 2nd Dynasty. The fact that they are, to date, unattested outside Saqqara suggests that their authority may have been confined to the north of Egypt. By contrast, graffiti in the Western Desert record an otherwise unknown king who, it seems, controlled or had access to parts of southern Egypt. Taken together, these six poorly-attested royal names and an obscure reference in the royal annals may suggest political fragmentation and a period of civil unrest during the middle of the 2nd Dynasty; but such a hypothesis remains speculative in the absence of more substantive evidence. A recent re-examination of the surviving inscriptions of Weneg suggests the possibility that he and Raneb may have been one and the same ruler; while not yet fully proven, this tantalizing suggestion merely underlines the extent to which our knowledge of 2nd-Dynasty history is incomplete and lacking in sound foundations. Ongoing excavations in the early royal cemeteries at Saqqara and Abydos may help to clarify our understanding.

“The 3rd Dynasty (c. 2670 – 2600 B.C.) is scarcely better known. It is dominated by the monuments of Netjerykhet—notably his Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara. The king himself is now firmly established by archaeological evidence as the first ruler of the 3rd Dynasty, despite the (erroneous) testimony of some ancient king-lists. It is interesting that Netjerykhet is nowhere directly named as his predecessor’s son; rather, contemporary inscriptions emphasize the role of a woman, Nimaathap— referred to as “mother of the king’s children” in the reign of Khasekhemwy, and as “king’s mother” in the reign of Netjerykhet—in the royal succession. Together with the prominence given to Netjerykhet’s wife and daughters on his monuments, and the fine, contemporary statue of a royal princess (Metropolitan Museum of Art 1999: Catalogue nos. 4, 7b, 16), the influence of Nimaathap may point to an important political and religious role for women in the 2nd-3rd dynasties.

“By contrast with the spectacular and lasting achievements of Netjerykhet, his three successors—Sekhemkhet, Khaba, and Sanakht—are shadowy figures, sparsely attested in contemporary inscriptions and signally lacking in major monuments. They seem likely, therefore, to have enjoyed only brief reigns, none more than ten years. Sekhemkhet’s own step pyramid enclosure, adjacent to his predecessor’s, never rose much above ground level. The equally unfinished “Layer Pyramid” at Zawiyet el-Aryan is attributed to Khaba on the basis of scanty, circumstantial evidence, while Sanakht appears not even to have embarked on a pyramid or similar monument—unless the unexcavated “Ptahhotep enclosure” to the west of the Step Pyramid dates to his reign. Partly through this lack of major dated monuments, the precise position and sequence of Khaba and Sanakht within the 3rd Dynasty also remain uncertain. Only Netjerykhet’s fourth successor and the last king of the dynasty, Huni, is firmly placed within the order of succession and reigned long enough to undertake a significant building program. Yet even he seems to have eschewed colossal architecture on the scale of the Step Pyramid, settling instead for a series of small monuments throughout Egypt to mark his power and serve as foci for the royal cult.”

Early Dynastic Period Stone Tools

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: The trend towards stone tool “standardization continued in the Early Dynastic Period (3030-2650 B.C.). At Helwan, finds were discovered from a flint workshop that obviously specialized in the production of large bifacial knives, sometimes of enormous dimensions. One such knife, probably used by King Djoser or a high priest during the burial of King Khasekhemwy at Abydos, was 72 centimeters long. Large bifacial knives were manufactured in special workshops either in settlements, e.g., at Buto, or next to cemeteries, as evidenced at Helwan. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

flint knife

“The use of flint knives is depicted in many slaughtering scenes in the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.) tombs of Giza and Saqqara. The mastaba of Ptahhotep serves as a good example, showing butchers cutting off the legs of cattle with large knives. In the lower register of this wall scene, at the left and in the middle of the upper register, a man is shown resharpening (Egyptian pdt) a used knife with a retouching stick.

“One of the most common tool types of the Early Dynastic Period down to the end of the 4th Dynasty is the once so-called “razor blade”, which is, in fact, a bi- truncated tool on a very regular, large blade. The early forms of the 1st Dynasty were oval in shape, becoming rectangular from the 2nd Dynasty onwards. The tool was used throughout the country and was supplied by specialized workshops. On the island of Elephantine, it is so common that it makes up one third of all tools dating to the Early Dynastic Period and the early Old Kingdom, and it was possibly as multi-functional as a Swiss Army Knife.”

Royal Tombs and Pyramids from the Second and Third Dynasties (2800-2600 B.C.)

Toby Wilkinson of Cambridge University wrote:“The surviving examples of royal mortuary architecture, at Saqqara and Abydos, thus dominate our view of the 2nd-3rd dynasties. While it may be misleading to place too much emphasis on this well-documented aspect of Early Dynastic culture (as against internal political, economic, and cultural change, for which there is precious little evidence), there is no doubt that royal funerary ideology and its architectural manifestation were particular concerns of the state, and were areas of innovation during the two centuries between the accession of Hetepsekhemwy and the death of Huni. [Source: Toby Wilkinson, Cambridge University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

mastaba tomb “Hetepsekhemwy, having presided at the burial of his predecessor, Qaa, and overseen the sealing of the latter’s tomb at Abydos, took the radical decision to re-locate the royal cemetery to the Memphite necropolis, specifically to North Saqqara. The site had been a focus for elite burial since the early 1st Dynasty, but had never before been used for kings’ tombs. The reasons for Hetepesekhemwy’s innovative policy can never be known, but they may have included family ties, political concerns, and theological developments. Certainly the form of the royal tomb in the early 2nd Dynasty suggests an evolution in the concept of the royal afterlife, with an explicit northward orientation of the tomb’s main axis signifying a new emphasis on the celestial realm—and, in particular, the circumpolar stars—as the king’s post-mortem destination. The name of Hetepsekhemwy’s funerary domain, 1r-xa-sbA, “Horus rises as a star,” points in the same direction. The geology of North Saqqara also influenced the design of the royal tomb, which now became rock-cut rather than brick- built. In other respects, however, such as the provision of a suite of rooms for the dead king’s ka, the tomb of Hetepsekhemwy maintained traditions established in the late Predynastic Period at Abydos.

“A tomb similar in design and proportions to Hetepsekhemwy’s and located immediately adjacent has been attributed to his second successor, Ninetjer, leaving the intervening king, Raneb, without a securely identified tomb. That he was buried at Saqqara can, however, be deduced from the discovery nearby of a finely carved funerary stela of red granite bearing Raneb’s serekh. It is clear from ongoing excavations at Saqqara that the early 2nd-Dynasty necropolis extends beyond the tombs of Hetepsekhemwy and Ninetjer, to the west, north, and south, so the tombs of additional kings almost certainly lie underneath the New Kingdom cemetery or among the subterranean galleries beneath the western massif of the Step Pyramid complex.

“When the royal necropolis was moved back to Abydos in the reign of Sekhemib/Peribsen (again, for unknown political and/or religious reasons), the design of the king’s tomb likewise reverted to a 1st-Dynasty model. But this may have been driven as much by geology and the absence of locally available high-quality building stone as by theological influences. Khasekhemwy seems to have aiming at a compromise design in his tomb at Abydos, which was built largely of mud brick (in 1st- Dynasty fashion), but with a longitudinal layout incorporating galleries of storage chambers (like the early 2nd-Dynasty royal tombs at Saqqara). His program to re-unite Lower and Upper Egypt and their distinct cultural traditions, announced also in the dual form of his name (Khasekhemwy, “the two powers have appeared”), was further emphasized in his construction of vast funerary enclosures at Hierakonpolis, Abydos, and Saqqara—the three most prominent ancient centers of royal mortuary and ceremonial architecture. The “Fort” at Hierakonpolis and the Shunet el- Zebib at Abydos stand to this day as the world’s oldest mud brick buildings. Khasekhemwy’s stonebuilt enclosure at Saqqara—assuming, as seems almost certain, that the Gisr el-Mudir is to be dated to his reign—is now much denuded, but its scale far surpasses that of its southern counterparts.

“Indeed, a richer understanding of the Gisr el-Mudir, including its architecture and construction, provides the context for the design and execution of the Step Pyramid complex in the following reign: Netjerykhet’s monument did not require as great a leap of imagination, organization, or technology as was previously thought. Nevertheless, by combining the royal funerary enclosure and the king’s tomb in a single monument, adding spaces for the eternal celebration of royal rituals, and orienting the whole complex towards the circumpolar stars, the Step Pyramid complex effectively brought together all the different strands of Early Dynastic royal funerary ideology and can be regarded as the summation of theological and architectural developments during the first two dynasties.. In its unprecedented use of stone, its innovative design (employing a visible pyramid to cover the burial chamber), its colossal scale, and the administrative effort required to build it, Netjerykhet’s monument marked the beginning of a new age and laid the foundations for the cultural achievements of the Old Kingdom.”

Religion in the Second and Third Dynasties

Toby Wilkinson of Cambridge University wrote: “The scale and growing sophistication of royal funerary monuments during the 2nd-3rd dynasties contrast sharply with the near- invisibility of temples or shrines to deities. Only a handful of sacred buildings are attested outside the royal necropoleis, but even here—at Hierakonpolis, Elkab, Gebelein, and Heliopolis—the surviving fragments of relief decoration emphasize the king and his role as founder of temples and companion of the gods. At Buto in the northwestern Delta, a large, official building of the 2nd Dynasty has been identified as a royal cult complex rather than a temple; a limestone pedestal in one of the innermost chambers may have supported a cult statue of the king, now lost. Hence, at sites rather than of local deities seems to have been the dominant feature of state religion in the 2nd-3rd dynasties. Likewise, contemporary seal-impressions and inscriptions on stone vases, when they mention deities at all, tend to emphasize gods and goddesses intimately connected with kingship—for example, Ash, the god of royal estates, or Hedjet, the divine embodiment of the white crown. [Source: Toby Wilkinson, Cambridge University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Taken together, the evidence—albeit slim and fragmentary—suggests that Pharaonic religion in its classic form was not yet established during the Early Dynastic Period. Rather, it seems to have been a development of later eras, a theological elaboration of a system designed, from the outset, to magnify the monarch and serve his interests. Beyond the royal court, private religious observance was an aspect of daily life from earliest times, but it seems to have had little connection with the realm of official, royal theology. Hence, archaeological excavations on Elephantine have revealed an early shrine underlying the later temple of Satet, but the extensive corpus of votive material does not point to any particular deity having been worshipped at the site; rather, the shrine may have been a general “sacred space,” used from Predynastic times as a focus of community worship.

part of a 2nd Dynasty stele

“The disconnect between state and private spheres of religious activity reflects a broader division in Egyptian society—present at all periods of Pharaonic civilization, but especially marked in the early dynasties—between the small ruling elite (pat) and the mass of the population (rekhyt). The sharp distinction between the pat and the rekhyt was one of the defining features of a society run by and for a restricted circle of royal kinsmen and acolytes. The structure of the Early Dynastic administration can be reconstructed from officials’ titles and the names of institutions preserved on seal-impressions, and it is the treasury—tasked with funding the state and its projects—that emerges as the most important department of government, closely followed by the royal household itself. Yet there are signs in the 2nd-3rd dynasties that the administration, including the highest offices of state, was beginning to be opened up to commoners. In the reign of Netjerykhet, several officials of apparent non-royal origin were appointed to prestigious posts. These included the controller of the royal barque, Ankhwa; the master of royal scribes and chief dentist, Hesira; the controller of the royal workshops, Khabausokar; and, most famous of all, the overseer of sculptors and painters, and presumed architect of the Step Pyramid complex, Imhotep. It seems that, for the first time, the early 3rd-Dynasty state, with its focus on large-scale royal building projects, relied on a close-knit cadre of trusted professionals to carry out the principal tasks of government.”

Government in the Second and Third Dynasties

Toby Wilkinson of Cambridge University wrote: “The introduction of job specialization within government circles can be seen in the same context: the 1st-Dynasty pattern of bureaucracy, with its diffuse portfolios of responsibilities, was simply not up to the task of managing an increasingly complex governmental machine. It is no coincidence that the post of “vizier”— a single individual, directly responsible to the king for the workings of the entire national administration—is first attested in inscriptions from the Step Pyramid complex. While the tripartite title of the vizier, tAjtj zAb TAtj, echoes an earlier model of officialdom that combined courtly, civil, and religious duties, the creation of the post itself reflects the new challenges faced by the Egyptian government at the dawn of the pyramid age. The emergence in the 3rd Dynasty of a fully diversified and professionalized national administration with a hierarchical structure is demonstrated in the autobiographical inscription of Metjen, who took full advantage of the opportunities afforded to ambitious and talented men . His career progression exemplifies the changes wrought in Egyptian society as a whole during the 2nd-3rd dynasties. [Source: Toby Wilkinson, Cambridge University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Alongside changes to the composition and structure of the administration, measures to improve the country’s economic productivity can also be linked to the state’s focus on royal building projects with their vast resource requirements. From tentative beginnings in the 1st Dynasty, provincial government via the nome system was fully realized during the 2nd- 3rd dynasties, and district administrators such as Sepa and Ankh enjoyed commensurately high status at court. By the beginning of the 4th Dynasty, state interference in local affairs extended to the forced resettlement of entire communities as royal estates were established and reorganized . To give the state better information for the purposes of taxation and economic control, a regular census of Egypt’s agricultural and mineral wealth was introduced in the early 2nd Dynasty, to judge from the royal annals preserved on the Palermo Stone. Decisive steps were also taken, at home and abroad, to increase government revenue. Mining expeditions to exploit Egypt’s mineral resources became a regular occurrence, yielding copper from Wadi Dara, el-Urf/Mongul South, and Gebel Zeit in the eastern desert, and turquoise from Wadi Maghara in Sinai . At the latter site, three 3rd-Dynasty kings— Netjerykhet, Sekhemkhet, and Sanakht—left commemorative inscriptions, emphasizing the royal/state character of the expeditions.

“Beyond Egypt’s borders, an intensification of long-distance trade swelled the state’s coffers still further. At the end of the 2nd Dynasty, the Egyptian government seems to have formally chosen Byblos, on the Lebanese coast, as the center of its trading activity—attracted, no doubt, by the port’s long history as an entrepôt for high-value commodities, and by the abundant supplies of good-quality timber in the vicinity. Access to these forests of coniferous wood permitted an upsurge in ship-building, which, in turn, facilitated a sharp increase in the volume of trade between Egypt and the Near East. The results of this commerce— notably the import of tin from Anatolia—can be seen in the tomb equipment of Khasekhemwy, which included the earliest bronze vessels yet discovered in Egypt.

“If Egypt’s engagement with the Near East in subsequent eras can be used as a guide to earlier periods, it is probable that the rise in economic interaction between Egypt and the Levant in the 2nd-3rd dynasties was accompanied by an increase in the number of foreigners settling in the Nile Valley. Because of the demands of Egyptian artistic and cultural decorum, such immigrants are difficult to identify in the textual or archaeological records, but a few examples from the early 4th Dynasty may indicate a more widespread phenomenon. From the beginning of the 2nd Dynasty, as far as we can judge, there also seems to have been a diminution in the official xenophobia directed against Setjet (the Near East), and the two trends may be connected. A final manifestation of Egypt’s increased economic activity, and its relentless search for mineral resources and trading opportunities, may have been a greater interest in its southern neighbor, Nubia. Evidence from the earliest levels at Buhen, near the second Nile cataract, suggests a permanent Egyptian presence as early as the 2nd Dynasty.

Abydos

“The availability of a richer array of raw materials combined with the rise of royal workshops led to advances in craftsmanship and technology, as attested by surviving artifacts from the 2nd-3rd dynasties. Sculptors achieved greater levels of refinement and sophistication, as shown in the terracotta lion and the large-scale statues of Khasekhem from Hierakonpolis, the statues of princess Redjief and other 3rd-Dynasty worthies, and the beautiful carved wooden panels of Hesira (Metropolitan Museum of Art 1999: Catalogue nos. 11-17). A greater confidence in the handling and dressing of stone was both a prerequisite for, and the result of, the realization of the Step Pyramid complex. Advances in metallurgy, with the advent of bronze technology, have already been noted. Beyond these few inscribed or royal objects, however, our knowledge of material culture in the 2nd-3rd dynasties is severely limited by the paucity of securely dated material from controlled excavations. There is, thus, immense potential for the study of unpublished data, the re-excavation of known sites, and new fieldwork to add to our understanding of this crucial, formative period.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024