Home | Category: Death and Mummies

BURIALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

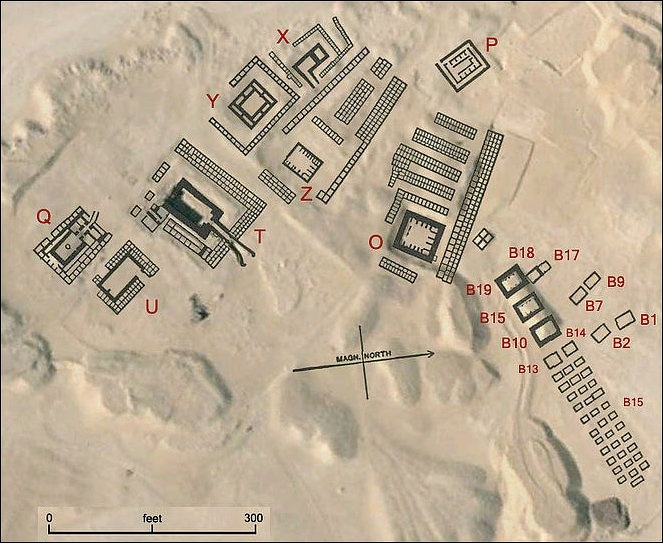

Chephren cemetery viewed from the Second Pyramid

Egyptian dead were always buried, never cremated. Up until Islamic times, the dead in Egypt were buried facing the rising sun in the East with the head pointing to the north. Cemeteries were always on the western side of the Nile because the sun set in the west. Often they were close enough to the river so that funeral processions coming down the Nile could easily reach the graves.

Ancient Egyptians who died around 3500 B.C. were often laid to rest lying on a mat on their left side in the fetal position, facing the west and the setting sun. In some cases the bodies were decapitated after death and placed back on the body in the tomb, which appears to indicate ritual dismemberment and reassemblage.

Most mummies were anonymous. The likenesses on the coffins often looked nothing like the mummy inside but were idealized representations. Royal mummies were placed in a series of coffins, which went inside a sarcophagus which went into a series of shrines. The inner coffins and the tombs were inscribed with hieroglyphic texts of protective spells. Some coffins were made of basalt. Some sarcophagus were made of red granite. the lid of a large sarcophagus could weigh 2.7 tons and be covered with hieroglyphics on one side and the goddess Nut in a transparent gown on the other. There were also reusable coffins. The outer coffin for King Tutankhamun was adorned with garlands of willow and olive leaves, wild celery, lotus pedals and cornflowers which suggests he was buried in the spring. See King Tutankhamun (King Tut).

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: ““Another practice that brought the deceased into the domestic realm was the interment of infants and fetuses within settlements. It has been suggested that the practice, best known from Lahun, reflects a foreign origin. Such burials are, however, recorded from other sites in Egypt, including Abydos and South Abydos, Deir el-Medina, and el-Amarna, and the practice is probably an indigenous one. Sometimes the burials include objects, suggesting that some funerary rites were carried out and that the infants were believed to have an existence in the afterlife. Did the families seek to keep them close, protecting and sustaining them in their journey through the underworld? Or did the liminal status of the infants offer to the living a channel of communication with the divine world? Much more work is needed on the subject to elucidate its meaning and origins within Egypt.” [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Human sacrifices may have been practiced by the earliest pharaohs (See History). Real people were not sacrificed and buried with the dead as was the case sometimes with the Mesopotamians and other cultures. This practice may have been practiced in the early days, which possibly is how the custom of burying substitutes and shabti figures began.

In the case of multiple burials in a single shaft, the deeper a body was buried, the more wealthy or important the individual was likely to have been in life. Hieroglyphics on coffins have yielded clues to status. Once lower levels were occupied, the shaft was filled with rubble. [Source: Jason Treat and Ben Scott, National Geographic, July 10, 2023]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

“Early Burial Customs in Northern Egypt (BAR International)

by Joanna Debowska-Ludwin (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Tomb in Ancient Egypt” by Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Tombs: The Culture of Life and Death” by Steven Snape (2011) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs” by Philip J. Watson (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Tomb and Beyond: Burial Customs of the Egyptian Officials” by Naguib Kanawati (2001) Amazon.com;

“Living with the Dead: Ancestor Worship and Mortuary Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Nicola Harrington (2012) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes” by Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes (2000) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor” by Nigel Strudwick (1999) Amazon.com;

Predynastic Burials in Egypt

Pre-Dynastic burial

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “In ancient Egypt, the primary evidence for the Predynastic Period, principally the fourth millennium B.C., derives from burials. In Upper Egypt, there is a clear trend over the period towards greater investment in mortuary facilities and rituals, experimentation in body treatments, and increasing disparity in burial form and content between a small number of elite and a larger non-elite population. In Maadi/Buto contexts in Lower Egypt, pit burials remained simple with minimal differentiation and less of a focus upon display-orientated rituals [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

It was from Upper Egyptian cemetery sites such as Naqada and Ballas and el- Abadiya and Hiw that the Predynastic was first recognized and classified. Over 15,000 burials are documented for Upper Egypt, but less than 600 Maadi/Buto graves from Lower Egypt are known. From the content and form of these burials, the chronological framework of the fourth millennium B.C. has been constructed and the nature and development of social complexity during the rise of the state charted. There has been a particular focus upon aspects of wealth and status differentiation following the work of Hoffman. The clear trend identified in these studies, for Naqadan burials at least, is for a widening disparity between graves in terms of the effort invested in tomb construction (size and architecture) and in the provision of grave goods. Less attention has been paid to other aspects of social identities represented in burials, such as gender, age, and ethnicity, although recent excavations at Adaima, Hierakonpolis, and in the Delta are providing firmer foundations for more nuanced interpretations, together with a reassessment of early twentieth century excavations.

“In comparison to Neolithic fifth millennium B.C. ‘house burials’, interred in what are probably the abandoned parts of settlements at el-Omari and Merimde Beni-Salame, most graves known from the Badarian and fourth millennium B.C. are from cemeteries set apart from habitation. Nevertheless, in both Upper and Lower Egypt some interments, predominately those of children, are still found within settlements, sometimes within large ceramic vessels (‘pot-burials’). This may account, to some extent, for the under-representation of children within most cemeteries.”

Location of Predynastic Burials in Egypt

Pre-Dynastic burial

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “In Upper Egypt, the earliest identified burials date to just before the fourth millennium B.C. and are considered to be Badarian burials. These are known principally from the locales of Badari, Mostagedda, and Matmar, although more limited evidence has been recognized further south to Hierakonpolis. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Naqada I burials are known to stretch further south into Lower Nubia, but none are attested north of the Badari region. These cemeteries were usually placed at the low desert above the floodplain, thus facilitating their preservation. More detrimental to the mortuary record has been grave robbing, an occurrence not restricted to modern times, and many interments were plundered shortly after the funeral by perpetrators who were aware of the goods interred within.

“From Naqada IIC on, burials with Upper Egyptian characteristics began to appear in Lower Egypt at Gerza, Haraga, Abusir el-Melek, and Minshat Abu Omar. These are associated with the spread, and eventual predominance, of Upper Egyptian social practices and ideology across Egypt. In Upper Egypt, the contrast between an emerging elite and non-elite is manifest starkly at three sites, hypothesized to be regional power centers of Upper Egypt, where discrete elite cemetery areas were maintained apart from the others. These comprise: Hierakonpolis, Locality 6; Naqada, Cemetery T; and Abydos, Cemetery U.

“Far fewer burials of the Maadi/Buto tradition are known in Lower Egypt, possibly due to Nile flooding and shifts in the river’s course, as well as the fact that such burials were only archaeologically recognized and published relatively recently. Those that have been found are roughly equivalent to mid- Naqada I to Naqada IIB/C. The eponymous settlement site of Maadi and associated cemetery Wadi Digla hold the largest concentration of material, with other notable remains at Heliopolis. Eleven graves at el-Saff represent the furthest south that burials of this sort are attested.”

Naqadan Burials

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “Predynastic burials were subterranean pits dug into the ground. Initially, during Badarian times, oval pits were the norm, but over the course of the Predynastic Period there was a trend towards larger, more rectangular graves. Nonetheless, many burials remained shallow and only large enough to accommodate a contracted body wrapped in a mat. Quantifying the proportion of such poor burials is problematic as they often went undocumented in early excavation reports or have been destroyed on account of their shallowness. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“In late Naqada II ( 3450–3300 B.C.), some funerary offerings in larger tombs came to be placed in separate niches, presaging the compartmentalization of Pharaonic Period tombs. A small percentage of Naqadan II/III tombs were plastered in or over with mud, or were lined or roofed with wood. Wood and pottery coffins are known by Naqada III. The use of mud-brick for the construction of subterranean tombs is attested at a few sites in late Naqada II, but by early Naqada III, this had been adopted as a standard feature of high-status burials, such as at Minshat Abu Omar. The series of Naqada III brick-lined tombs at Abydos, some with multiple chambers, form direct precursors to the 1st and 2nd Dynasty royal tombs that extend south from this location.

“The presence of an above ground feature demarcating burial plots may be assumed from the infrequency of inter-cutting graves and underlines the importance of social memory to ancient communities. There is limited evidence for the form these memorials might have taken, but a simple hillock, as has been observed at Adaima, is one possibility. In the elite cemetery at Hierakonpolis, Locality 6, post holes have been found around some graves, including a Naqada IIA-B tomb (Tomb 23), implying that some form of covering was erected over the burial chamber. Measuring 5.5 meters by 3.1 meters, it is the largest tomb known for this date. Also unique to Hierakonpolis is a large (4.5 x 2 x 1.5 meters deep) mud-brick-lined pit with painted plaster walls, known as Tomb 100; it is dated to Naqada IIC, which attests to an early date for tomb painting in an elite context. On a white mud-plastered background, images of animals, boats, and humans in combat are portrayed in red and black.”

Abydos

Treatment of Corpses at Naqadan Burials

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “From Badarian times onward, great care, attention, and reverence was conferred upon the disposal of the dead. There is the general tendency to interpret these mortuary contexts as simply being for the benefit of the deceased and their afterlife, but the social significance of these practices for the surviving community should also be acknowledged. With regard to the latter, scholars have interpreted Naqadan funerary rituals in terms of competitive status display, identity expression, and social memory formation. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“In Badarian burials, corpses were generally contracted on their left side with heads positioned south, facing west, and with hands clasped in front of the face. Bodies were carefully laid upon a mat and wrapped in animal skins, with occasional addition of a pillow made from straw or rolled-up animal skin.

“Naqadan graves are similar, and although single inhumation was the standard arrangement, multiple burials do occur— usually two to three bodies, much more rarely four or five. It has been suggested that multiple burials are more common in earlier Naqada I Periods, but a statistical survey is wanting.

“In Naqada I, bodies were also predominately placed on the left side with the head to the south and face to the west. This position was still the most common in Naqada II, although more deviations in alignment occurred, particularly for those Naqadan burials in the north. At Gerza, for instance, several combinations of position are evident. In Naqada III, the cemeteries of Tarkhan and Tura display a greater alternation in alignment; on average, about 70 percent were positioned with heads pointed to the south and 30 percent to the north, 72 percent were faced west and 28 percent east.

“In addition to inhumation of the complete corpse, other body treatments are known but are far less frequent. These include post- interment removal of the skull, rearrangement of skeletal remains within the grave, and the first occurrence of mummification in the form of resin-soaked linen pressed upon the hands and around the face of some Naqada IIA-B cadavers.”

Lower Egyptian/Maadi/Buto Burials

Pre-Dynastic burial

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “In comparison to Upper Egyptian tombs, Maadi/Buto burials in Lower Egypt are simpler and are poorly represented in the archaeological record. These graves were oval pits into which the deceased was laid in a contracted position, sometimes wrapped in a mat or other fabric, with the head usually positioned south and facing east. No collective burials are known, but the single inhumations display minimal differentiation in size and provision. Interspersed amongst the human burials were individual burials for goats and a dog, which were accompanied by some ceramics. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Grave goods are scarce, and most burials at Maadi and Wadi Digla were devoid of offerings. Some contained a single vessel, although a minority contained more—the maximum found at Maadi was eight and at Heliopolis ten. Inclusions of other artifact classes within the burials are rare. Aspatharia rubens shells, flint bladelets, gray ore, and malachite pigmentation were documented in a few of the graves at Wadi Digla. One rhomboid palette, an ivory comb, and a single stone vessel were exceptional additions to a few graves in the Wadi Digla cemetery.

“Thus, in contrast to the Naqadan burials, the body at these sites was the primary focus of the grave rather than acting as a foundation around which meanings, relationships, and social statements could be represented by the juxtaposition of several categories of artifacts. This dearth of material is more likely to be a matter of social custom rather than a reflection of the poverty of this society, for the associated settlement deposits displayed evidence for significant amounts of copper, stone vases, as well as examples of locally styled, decorated pottery and anthropoid figures. Therefore, the simpler nature of these burials is not to suggest these communities were any less complex in the social management of death, which may have been conducted away from the cemetery site or in an intangible manner.”

Burial Chambers of the Pyramids

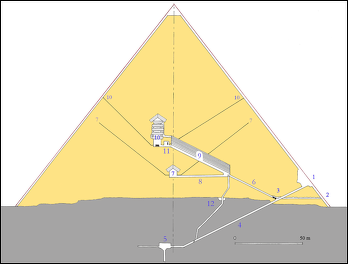

On what is inside the Great Pyramid in Giza, Dr Aidan Dodson wrote for BBC:“At first, the burial chamber was to be placed deep underground, with a descending passage and an initial room being carved out of the living rock. It seems, however, that it was decided that a stone sarcophagus-not previously used for kings-should be installed. Such an item would not pass down the descending corridor, and since the pyramid had already risen some distance above its foundations, the only solution was to place a new burial chamber-uniquely-high up in the superstructure, where the sarcophagus could be installed before the chamber walls were built. The architects of later pyramids ensured that there was adequate access to underground chambers by using cut-and-cover techniques rather than tunnelling. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Burial chamber of the Pyramid of Cheops

“Two successive intended burial chambers were constructed in the body of the pyramid, the final one lying at the end of an impressive corbel-roofed passage, which seems originally to have been intended simply as a storage-place for the plug-blocks of stone that were made to slide down to block access to the upper chambers after the burial. Corbel-roofing, where each course of the wall blocks are set a little further in than the previous one, allowed passages to be rather wider than would have been felt to be safe with flat ceilings, and are a distinctive feature of the earliest pyramids and tombs of the Fourth Dynasty, to which Khufu belonged. |::|

“The burial took place in that final burial chamber, nowadays dubbed the King's Chamber. An impressive piece of architecture, this granite room was surmounted by a series of 'relieving' chambers that were intended to reduce the weight of masonry pressing down on the ceiling of the burial chamber itself. At the west end of the chamber lay the sarcophagus, now lidless and mutilated. |::|

“It is unclear when the pyramid was first robbed, although some Arab accounts suggest that human remains were found in the sarcophagus early in the ninth century AD. As for what else may have been in the chamber when Khufu was laid to rest, there will have been a canopic chest for his embalmed internal organs, together with furniture and similar items. Examples of such simple, but exquisite, gold-encased items were found in the nearby tomb of Khufu's mother in 1925. |::|

“So-called airshafts, only 20cm (8in) square, leave the north and south walls of the chamber and emerge high up on the corresponding faces of the pyramid. These also were found in the original high-level burial chamber, and seem to have been aimed at particular stars, implying a stellar aspect to the king's afterlife-although as we have seen he was later more closely associated with the sun. Interestingly, the pyramid for Khufu's immediate successor, Djedefre, bore a name that described the king as a 'shining star'.” |::|

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Aligned with Winter Solstice Sunrise

In July 2022, in an article published in published in the journal Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, archaeologists announced that they had unearthed an unfinished, 3,800-year-old ancient Egyptian tomb with a chapel perfectly aligned with the sunrise on the winter solstice. Archaeologists say that this might be the oldest known tomb in Egypt that is aligned with the winter solstice. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The tomb, near modern-day Aswan, was built during Egypt's 12th dynasty, part of a time period sometimes called the "Middle Kingdom" in which Egypt thrived. mummies.[Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 29, 2022]

Located in the Qubbet el-Hawa necropolis, the tomb held the burials of two governors. In ancient times, graverobbers plundered many of the artifacts placed in the tomb, including the governors' The name of the governor who originally built the tomb is unknown, while the other governor buried there was named Heqaib III according to an inscription found in the tomb and in historical records. Both governors were in charge of the nearby town of Elephantine, albeit at different times, the team noted in a statement.

The tomb's chapel contains a niche that was originally intended to hold a statue of the governor who built the tomb, the team wrote in the study. The tomb and the statue were never completed, study co-author Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, an Egyptologist and archaeologist at the University of Jaén in Spain, told Live Science. Just outside the tomb, the team "found an unfinished statue" that was supposed to be completed and put in the niche, said Jiménez-Serrano, who directs the team's excavations at the site, noting that it's not clear why the tomb was left unfinished.

The entranceway to the chapel was built in such a way that the rays of the sun could enter and light the chapel during the winter solstice, which occurs annually on December 21 or December 22. In effect, had it been completed, the governor's statue and chapel would have been bathed in light during the sunrise of every winter solstice, the day with the fewest hours of daylight. It may be the oldest known tomb in Egypt that is aligned with the winter solstice, the researchers noted.

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Ancient Egyptians believed that the sunlight hitting the statue transmitted energy that helped reactivate the vital force of the mummified body, which was buried directly below. To allow the greatest amount of sunlight to reach the chapel, the tomb’s doorway stood around 16 feet tall and was always open. “We found no trace of a door,” says Egyptologist Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano of the University of Jaén, who led the excavation of the tomb. “It’s clear that this entrance was made to receive the sun’s rays.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2023]

According to Lola Joyanes, a professor of architecture at the University of Málaga, the tomb was actually angled 0.74 degrees south of a precise orientation toward the winter solstice sunrise. This appears to have been done intentionally, so that the brightest star in the sky—Sothis, now known as Sirius—would be visible from the tomb’s niche on the summer solstice.The summer solstice generally coincided with the beginning of the annual Nile flood, which was key to Egypt’s agricultural success. As such, both the summer and the winter solstice were associated with resurrection. “The architect or designer of the tomb was a genius,” says Jiménez-Serrano, “and showed great imagination in combining these two celestial events in a single monument.”

Why did ancient Egyptians value the solstice? The winter solstice had an important meaning for the ancient Egyptians, the researchers told Live Science. "The winter solstice marked the beginning of the daily victory of light against darkness, culminating in the summer solstice, the longest day on the earthly plane," study lead author María Dolores Joyanes Díaz, a researcher at the University of Málaga in Spain, told Live Science.

Supplies for the After-Life in Ancient Egypt

palm trees

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: “The tomb-owner would continue after death the occupations of this life and so everything required was packed in the tomb along with the body. Writing materials were often supplied along with clothing, wigs, hairdressing supplies and assorted tools, depending on the occupation of the deceased. [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ==]

“Often model tools rather than full size ones would be placed in the tomb; models were cheaper and took up less space and in the after-life would be magically transformed into the real thing. The images presented here include a headrest, glass vessels which may have contained perfume and a slate palette for grinding make-up. Food was provided for the deceased and should the expected regular offerings of the descendants cease, food depicted on the walls of the tomb would be magically transformed to supply the needs of the dead.” ==

Items excavated from tombs include include “a triangular shaped piece of bread (part of the food offerings from a tomb) along with two tomb scenes. The latter contain representations of food items which the tomb owner would have eaten in his lifetime and hoped to eat in the after-life. The two tomb scenes show the tomb owners sitting in front of offering tables piled high with bread. The representations of food, along with the accompanying prayers were thought to supply the tomb owner once the actual food offerings stopped.” ==

Ken Johnson wrote in New York Times that the ancient Egyptians believed that life “was only a prologue to the main attraction, the afterlife, and they devoted much of their tremendous creative and technological ingenuity to ensuring that their dead — the wealthy ones, anyway — would have everything needed on the next plane of existence. They pickled the bodies of the deceased, stocked their graves and tombs with food, drink, jewelry, furniture, pets, reading material and whatever else that might come in handy upon awakening in the next dimension." [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, March 11, 2010 ***]

See Separate Article: GRAVE GOODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

4,000-Year-Old False Door to the Afterlife

A limestone stela, found at the tomb of a woman named Hemi-Ra, who lived during Egypt’s First Intermediate Period (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.) was a false door that served as a portal between the tomb and the afterlife. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

Hemi-Ra’s false door is unusual for a number of reasons, including that it was made for a woman. Of 680 known false doors and funerary stelas dating from the twentythird to twenty-first century B.C. studied by Pitkin, just 101 were designed for women. According to Fischer, the door features representations of Hemi-Ra at three distinct stages of her life. In the central panel near the top of the stela, she is depicted as a woman in her prime sitting before a table laden with offerings. At the bottom of the door, in the center, she is portrayed as a seated young girl, and as an older woman with drooping breasts on the outer edges. This is highly unusual, says Pitkin, as the deceased was typically represented only at the peak of vitality and health. A number of the figures at the bottom of the door have masculine features, such as legs spaced apart. However, the figures on the far left and far right are portrayed with full-frontal breasts; this is extremely uncommon in two-dimensional ancient Egyptian art.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Magical Mystery Door by Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024