Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

NEOLITHIC AND PREDYNASTIC EGYPT

Pre-dynastic burial

Pre-Dynastic Ages and Cultures of Ancient Egypt

Prehistoric Era

Lower Paleolithic Age (250,000-90,000 B.C.)

Middle Paleolithic Age (90,000-30,000 B.C.

Late Paleolithic Age (30,000-7000 B.C.)

Neolithic Age (7000-4800 B.C.)

Predynastic Period (4800-3050 B.C.)

Upper Egypt

Badarian Culture (4800-4200 B.C.)

Amratian Culture (4200-3700 B.C.)

Gerzean A Culture (3700-3250 B.C.)

Gerzean B Culture (3250-3050 B.C.)

Lower Egypt

Fayum A Culture (4800-4250 B.C.)

Merimde Culture (4500-3500 B.C.)

Archaic Period (3100-050-2705 B.C.)

Villages that extensively used agriculture began to appear in Egypt around 5000 B.C. By 4100 B.C., permanent year-round agricultural villages had been established in parts of Egypt, Katary wrote. Some year-round settlements eventually grew into cities. Naqada and Hierakonpolis (also known as Nekhen) became important urban centers between 3500 B.C. and 3000 B.C., Steven Snape, an honorary professor of Egyptian archaeology at the University of Liverpool in the U.K., wrote in his book "The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt" (Thames & Hudson, 2014). [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Before the Pharaohs: Exploring the Archaeology of Stone Age Egypt” by Julian Heath (2021) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Egypt, Socioeconomic Transformations in North-east Africa from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Neolithic, 24.000 to 4.000 BC by G. J. Tassie (2014) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt: From the First Farmers to the Great Pyramid” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of the First Farmer-Herders in Egypt: New insights into the Fayum Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic” by N. Shirai (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Stone Age In Egypt: A Record Of Recently Discovered Implements And Products Of Handicraft Of The Archaic Nilotic Races Inhabiting The Thebaid” (1914) by Robert De Rustafjaell (Author) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, c.10,000 to 2,650 BC” (Cambridge World Archaeology) by David Wengrow (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond by Yoshihiro Nishiaki, Takeru Akazawa, Editors Amazon.com;

” Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East”

by A. Nigel Goring-Morris, Anna Belfer-Cohen (2017) Amazon.com;

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

“Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: 15,000 Years of Crises, Setbacks, and Adaptation” by William R. Thompson and Leila Zakhirova (2021) Amazon.com;

“When the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to Be” by Martin Williams Amazon.com;

“The Green Sahara: Climate Change, Hydrologic History and Human Occupation”

by Ronald G. Blom (2009) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Predynastic and Archaic Periods of Egyptian History

The Predynastic Period (5464-3414 B.C.) is the period when hunter-gatherers broke away from their Neolithic ways and began organizing into a farming society. This along with great technological, religious, funerary and social advances caused village groups to consolidate into fledgling city-state organization, and this in turn helped urban life, writing, trading with other cultures, ornamental pottery and a strong belief in the afterlife to develop. Food was plentiful. Animals such as dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, geese and pigs had been domesticated. As time went on the main component of Egyptian civilization began to take shape. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Prior to 3000 B.C., Egypt seemed to be divided into a large number of small priestly-governed states each with its own names for commonly accepted divinities. About 3000 B.C. Egypt was unified by a conquering family out of the southern city of Thebes. The new dynasty placed its capital in the city of Memphis which lay at the point where the narrow valley of the Nile broadened into the Delta. This was the boundary, the Balance of the Two Lands (Upper and Lower Egypt); also called the Two Ladies. Half the usable soil of Egypt lay upriver (south), the rest lay down-river (north). [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

The Archaic Period (3414-3100 B.C.) is characterized by the consolidation of the Egyptian state. It was ensured by the development of a centralized administration system and a court-centered Great Tradition based upon the united Egypt. After this, even in times of political crisis, Egypt was dominated by the Egyptian elite. The royal court set the cultural standards for the entire country, making the king the fountainhead not only of power and preferment, but also as a member of the elite way of life. +\

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote: “Present day scholars consider the late Predynastic Period as a crucial phase in the history of ancient Egypt. Its theoretical characterization remains problematic, given that a rather uncritical acceptance of evolutionist theories has produced a multiplicity of terms whose conceptual status remains vague or scantily discussed (chiefdoms, proto-kingdoms, proto-states, early states, etc.). Another disagreement exists around the very nature of the state. In general, those authors whose definition of the state highlights the existence of a political- administrative apparatus ruling over a large territory, as it is known from Dynasty 1 on, tend to consider the late Predynastic Period as a formative phase; on the other hand, those authors who place more emphasis on social stratification and coercive practices tend to attribute state origins to earlier periods (mainly, Naqada IIc), so that Naqada IIIa-b is seen as a phase of strengthening for state dynamics. Be this as it may, most researchers would agree that this is a decisive period for the constitution of a new mode of social and political organization, an order radically different from that which prevailed in previous eras—based on kinship practices— which would predominate in the Nile Valley during the following three millennia.

See Separate Articles: EARLY PRE-DYNASTIC EGYPT (4500-4000 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com LATE PRE-DYNASTIC EGYPT (3,500-3,300 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Neolithic People that Lived in Egypt 11,000 to 6,000 Years Ago

About 9,300-4,000 B.C., enigmatic, little-studied Neolithic peoples flourished in Egypt. Their lifestyles and cultural innovations provided very foundation for the advanced civilisations to come. Joel D. Irish and Jacek Kabacinski, who are excavating six Neolithic sites in Egypt’s Western Desert, wrote: One reason why we know so little about Neolithic Egypt is that the sites are often inaccessible, lying beneath the Nile’s former flood plain or in outlying deserts. The sites we are currently excavating lie along the former shores of an extinct seasonal lake near a place called Gebel Ramlah. Though not lush, the Neolithic was wetter than today, which allowed these ancient herders to populate what is now the middle of nowhere. We focus on the Final Neolithic (4,600-4,000 B.C.), which was built on the success of the Late Neolithic (5,500-4,650 B.C.) with domesticated cattle and goats, wild plant processing and cattle burials. These people also made apparent megaliths, shrines and even calendar circles – which look a bit like a mini Stonehenge. [Source: Joel D. Irish, Professor and Subject Leader, Anthropology and Archaeology, Liverpool John Moores University, Jacek Kabacinski, Research fellow at the Institute of Archaeology, Polish Academy of Sciences, and Czekaj- Zastawny Agnieszka, Associate professor, Polish Academy of Sciences,The Conversation, August 1, 2019]

“During the final part of the Neolithic, people started burying the dead in formal cemeteries. Skeletons provide critical information because they are from once living people who interacted with the cultural and physical environments. Health, relationships, diet and even psychological experiences can leave telltale signs on teeth and bone. In 2001-2003 we excavated three cemeteries from this era – the first in the western desert – where we uncovered and studied 68 skeletons. The graves were full of artefacts, with ornamental pottery, sea shells, stone and ostrich eggshell jewellery. We also discovered carved mica (a silicate mineral) and animal remains, as well as elaborate cosmetic tools for women and stone weapons for men. We learned that these people enjoyed low childhood mortality, tall stature and long life. Men averaged 170 centimeters, while women were about 160 centimeters. Most men and women lived beyond 40 years, with some into their 50s – a long time in those days.

“Strangely, in 2009-2016, we dug two more cemeteries that were very different. After analysing another 130 skeletons, we discovered that few artefacts accompanied them, and that they suffered from higher childhood mortality as well as shorter lives and stature. We’re talking several centimetres shorter and perhaps ten years younger for adults of both sexes. Astonishingly, the largest of these two cemeteries had a separate burial area for children under three years of age, but mostly infants including late-term foetuses. Three women buried with infants were also found, so perhaps they died in childbirth. In fact, this is the world’s earliest known infant cemetery.

So what can this tell us about these peoples, let alone their descendants? As it turns out, a lot. We can use the findings to make interpretations about gender, life-stage, well-being, status and other things. “For example, why were there such differences between the two grave sites? They could have been separate populations, but it is unlikely based on overall physical similarities. So perhaps they imply variation by status – with one graveyard being for the elite and the other for workers. This is the earliest such evidence in Egypt.

“The sites also shed light on the family structures of the time. The overall sex ratio across all cemeteries is three women to each man, which may indicate polygamy. However, the total number of burials and a lack of reference to individual houses suggests these were extended family cemeteries. We also believe that attainment of “personhood” – the age children are socialised into being “people” – was from three years, given their inclusion in adult cemeteries.

“There is also clear evidence of respect for previously buried people by later mourners reusing the graves to bury their dead. When coming across old skeletons, they often carefully repositioned the bones of these ancestors. In some interesting cases, they even made attempts to “reconstruct” the skeletons by replacing teeth that had fallen out back into the skeleton – and not always correctly. These behavioural indicators, together with the seemingly innovative technological and ceremonial architecture mentioned earlier, such as the calendar circles and shrines, imply a level of sophistication well beyond that of simple herders. Taken together, the findings provide a glimpse of things yet to come in Ancient Egypt.

Green Sahara

Egypt's climate was much wetter in prehistoric times than it is today, and some areas that are now barren desert were green and relatively wet. One famous archaeological site that illustrates this is the "Cave of Swimmers" on the Gilf Kebir plateau in southwestern Egypt. The area is desert now, but thousands of years ago, it was wetter and figures in "Cave of Swimmers" appears to be people swimming, according to the British Museum. This rock art dates back between 6,000 and 9,000 years ago. The wetter period ended around 5,000 years ago, and since then, the deserts of Egypt have remained pretty similar to those that exist now, Marilyn Milton Simpson, a professor of classics at Yale University, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 6, 2022]

Tadrart Acacus, Libya

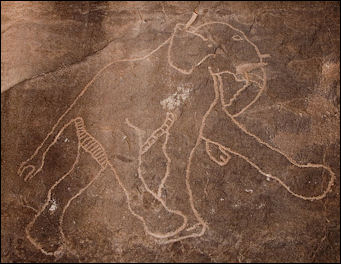

Other Extraordinary images of animals and people from a time when the Sahara was greener and more like a savannah have been left behind. Engravings of hippos and crocodiles are offered as evidence of a wetter climate. Most of the Saharan rock is found in Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Niger and to a lesser extent Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia and some of the Sahel countries. Particularly rich areas include the Air mountains in Niger, the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau in southeastern Algeria, and the Fezzan region of southwest Libya. Some of the art found in the Sahara region is strikingly similar to rock art found in southern Africa. Scholars debate whether it has links to European prehistoric cave art or is independent of that. [Source: David Coulson, National Geographic, June 1999; Henri Lhote, National Geographic, August 1987]

During the last 300,000 years there have been major periods of alternating wet and dry climates in the Sahara which in many cases were linked to the Ice Age eras when huge glaciers covered much of Europe and North America. Wet periods in the Sahara often occurred when the ice ages were waning. The last major rainy period in the Sahara lasted from about 12,000, when the last Ice Age began to wan in Europe, to 5,000 years ago. Temperatures and rainfall peaked around 9,000 years ago during the so-called Holocene Optimum.

See Separate Article: CLIMATE CHANGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: GREEN SAHARA, DROUGHT, EMPIRE COLLAPSE? africame.factsanddetails.com

Epipalaeolthic (7000-6000 B.C.) Stone Tools in Egypt

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: “The microlithic character of stone tool assemblages remained more or less intact during the Epipalaeolithic (7000-6000 B.C.), but showed influences from the Levant. Tools from Helwan are dominated by scalene bladelet tools, backed triangles, and lunates with some so-called Helwan points – an elongated projectile point with bilateral notches and a short tang. Retouch can cover the whole point, the tip, or just the hafting area. The majority of these points do not exactly resemble Egyptian points, and their likely origin is the Sinai and the southern Levant, with the best parallels from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B. In the Fayum, the Epipalaeolithic is known as Qarunian or Fayum B, and dates to approximately 8200-7200 BP. The lithic industry possesses a microlithic character based on backed or scalene bladelets, lunates, and triangles. The toolkit ranges from backed pieces (more than 50 percent of all the tools), notched and denticulated tools, geometrics, and some microburins, to a few endscrapers and even rarer perforators. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Badari culture scraper

“In Upper Egypt, the campsites of Elkab (c. 8000 BP) yielded a lithic industry, the Elkabian, based on wadi pebbles and consisting mainly of bladelets as well as blade tools. Amongst the bladelet tools are backed pieces, lunates, notches, denticulates, and geometrics and microburins. At the Epipalaeolithic site at Tree Shelter in the Eastern Desert, approximately 25 kilometers west of Quseir, hunter-gatherers already visited the place around 7000 B.C.. Overall, their lithic industry is strikingly similar to the Elkabian and is characterized by the production of blades and bladelets.

“Yet with respect to tools, endscrapers are rare at Elkab, while at Tree Shelter they account for the majority of tools, indicating hide preparation. Surprisingly, there was also a bifacial arrowhead among the stone tools at Tree Shelter, thus introducing bifacial flaking to this area. The lithic assemblages from the Eastern Desert and Elkab show similarities with sites in the Western Desert, where a similar bladelet technology can be found at sites such as E-72- 5 in the Dyke area, and denticulated, notched pieces and microburins are common tool types. This type of assemblage is also quite similar to the inventories associated with the “Early Neolitihic” sites at el-Ghorab and Nabta Playa in the Western Desert.

Neolithic (6000-4500 B.C.) Stone Tools in Egypt

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: “There are several sites in the Western Desert of post-Palaeolithic date that had an important influence on the development of Predynastic stone tool technology. In the Dakhla oasis we find the Beshendi and Sheikh Muftah industries. The former is a flake industry based on small flint nodules and quartzite. The inventories are characterized by many projectile points, up to 40 percent of all the tools, many of them bifacially retouched. There are also large bifacial tools present such as foliates and knives. Notched or denticulated pieces, scrapers, perforators, and side-blow flakes complement the tool kit. At Sheikh Muftah sites, imported tabular flint, which was often heat-treated, was the preferred raw material for perforators, scrapers, and denticulated pieces. There are fewer projectile points; a bifacial, tanged arrowhead is the major projectile form. Side-blow flakes, picks, sickles, and a few knives are present as well. Bifacial tools are also found in assemblages from the Farafra oasis. Calibrated dates for some sites are in the range of around 5900-6500 B.C.. Many bifacial tools also come from Rohlf’s Cave at Djara, where large, leaf-shaped, bifacial knives with fine, parallel ripples dominate the stone tool assemblages. Common elements at the sites listed above are projectile points and side-blow flakes. Many of the sites in the Western Desert share several Neolithic characteristics, such as pottery and grinding stones, as well as domesticated cattle and a lithic industry with bifacial tools, such as arrowheads, foliates, and knives. The Eastern Desert is by far less well explored in comparison to the Western Desert. During the Neolithic, herders came to the already- mentioned site of Tree Shelter, now bringing with them herds of sheep and goat. Irregular visits to the site ended in approximately 3700 B.C.. At the nearby site of Sodmein Cave, people also came to the area, bringing with them large herds of sheep/goat as well. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Most of the Neolithic sites in the Nile Valley and the adjacent Fayum oasis cover the time span of the fifth millennium B.C., with the Fayum A culture probably setting off the sequence in the second half of the sixth millennium B.C. The lithic industry of Fayum A is generally characterized by a flake industry with frequent denticulates, notched pieces, and retouched flakes. Also present are bifacial tools and scrapers on side-blow flakes. Axes often possess a polished working edge. The typical projectile point was the so-called bifacial “Fayum point” with a concave hollow base and long wings.

flint knives

“The site of Merimde Beni-Salame provides a sequence of almost 1000 years during the late 6th and first half of the fifth millennium B.C.. The most ancient level is the so-called “Urschicht,” with a flake-blade industry using mainly light brown terrace pebbles. Dorsal retouching is common, while ventral retouches remained scarce, as did end retouching. Coarse tools are represented by scrapers on core caps and some bifacially retouched tools. Amongst the arrowheads, a small artifact stands out. It was completely retouched on the dorsal, while the ventral shows only retouching at the tip and along the shaft. The projectile point has fins and two opposite notches on either margin, similar to the Epipalaeolithic Helwan points. The lithic industry of level II is of a very different character, dominated by bifacials. Amongst the various types of bifacials are perforators, sickles, and denticulates, with the latter two often bearing sickle sheen. Another group of bifacial tools are axes with polished cutting edges. A new form of projectile point had a triangular shape with straight ending wings, sometimes finely denticulated edges, and a concave base. Blades were still produced and turned into simple blade tools, but their length increased when compared to the Urschicht. The lithic industry of the youngest phase at Merimde (level III-V) can be seen as a continuation of the bifacial industry from level II. Flintknappers again made use of wadi pebbles, albeit on a small scale. The form of the triangular projectile point was becoming more clearly defined in level IV when it reaches the classical Merimde point for arrows and harpoons alike.

“The lithic industry from el-Omari, south of modern Cairo, is based on flakes that overwhelmingly use the locally available, roughly fist-sized gravel flint, resulting in relatively small flakes, alongside a core industry for bifacial tools. The latter especially show similarities with Merimde Beni-Salame and the Fayum Neolithic. The main tool types are denticulated and notched pieces, perforators, various retouched pieces, scrapers, and a few sickle blades. A unique tool at el-Omari is the handled knife made on large blades. Made from a grayish flint that was brought to the site in the form of blanks, they feature a steep retouching on the back and a cutting edge on the right and left margin. Microliths are another element at el-Omari reminiscent of an Epipalaeolithic tradition. The polished axes from the later phase at el- Omari, however, point to a southern tradition from the Badari region. This late Neolithic industry in Upper Egypt was a flake-blade industry with various retouched pieces, drills, and endscrapers as the dominant tool types. Concave-base projectile points are also similar to those from Lower Egypt, but are often more finely made. Knives, adzes, or fishtail knives were rare elements. Although the exact chronological position of the Badarian remains somewhat debated, it is clear that it gives the first evidence for agriculture in Upper Egypt, and that in the region it developed into the Naqada I culture, which is characterized, in regard to its lithic material, by the Mostagedda industry. All in all, the Badarian stone industry is not merely a rough core industry, but a flake-blade industry with increasing standardization of lithic implements.

Early Agriculture and Cattle Domestication in Egypt

Sometime during the final Paleolithic period and the Neolithic era, a revolution occurred in food production. Meat ceased to be the chief article of diet and was replaced by plants such as wheat and barley grown extensively as crops and not gathered at random in the wild. In Egypt during the Tasian period (named for Deir Tasi in Middle Egypt) which began between 10,000 and 7,000 B.C., man began to cultivate grains, including wheat, barley and flax. During this period, people began to settle along the banks of the Nile and evolved from hunters and gatherers to settled, subsistence agriculturalists. In a large Neolithic village near the southwest edge of the delta at Meremdeh Beni-Salamah, oval huts of unbaked mud bricks and a large central granary were found, indicating the development of co-operative enterprise. Woven plant fibers and ornaments of shell, bone and ivory reflect manufacturing and artistic skill. Similar settlements have been found in the Faiyum, an ancient oasis west of the Nile.

Cattle are believed to have been domesticated from aurochs from Western Asia between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago. Evidence of domesticated cattle has been found in archeological sites dated to 6400 B.C. Cattle appears to have been domesticated separately in Africa — with the earliest evidence of this happening occurring in northwestern Sudan about 8,000 years ago.Professor Mary Prendergast wrote: Archaeological research shows herding began to appear in and spread from what is now Egypt around 8,000 years ago. By 5,000 years ago, herders were burying their dead in elaborate monumental cemeteries near a lakeshore in Kenya. Two millennia later, pastoralist settlements were present across a wide part of East Africa. [Source: Mary Prendergast, Professor of Anthropology, Saint Louis University — Madrid, The Conversation, May 30, 2019]

The relatively egalitarian tribal structure of the Nile Valley broke down because of the need to manage and control the new agricultural economy and the surplus it generated. Long-distance trade within Egypt, a high degree of craft specialization, and sustained contacts with southwest Asia encouraged the development of towns and a hierarchical structure with power residing in a headman who was believed to be able to control the Nile flood. The headman's power rested on his reputation as a "rainmaker king." The towns became trading centers, political centers, and cult centers. Egyptologists disagree as to when these small, autonomous communities were unified into the separate kingdoms of Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt and as to when the two kingdoms were united under one king. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

See Separate Article FIRST CATTLE AND COW DOMESTICATION factsanddetails.com

Evidence of Cattle Herding and Bone Bloodletting Tools from 7,000-Year-Old Site in Northern Sudan

Aspen Pflughoeft wrote in the Miami Herald: Looking out across the desert landscape of northern Sudan, it’s easy to imagine what the arid land looked like several millennia ago. Herds of cattle would pass through, drawn to the lush banks of the Nile River. Communities of people would settle along this intersection of water and wildlife. A truck driver uncovered evidence of such a scene while doing construction work in the Letti Basin, Science in Poland reported in a March 23 2023 news release. The wheel of the truck fell into a hole, and when the driver tried to drive out, the truck threw human bones and ceramics to the surface. As archaeologists soon realized, the construction crew had stumbled upon a 7,000-year-old burial chamber. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, March 24, 2023]

“Excavating the area, archaeologists found a cemetery rich with grave goods. The burials belonged to some of the region’s first cattle breeders. At one very deep burial pit, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a tall elderly man covered in fragments of animal skin. The animal skin had been colored with a red mineral known as ochre, the release said. Ochre is a type of dye used since the cave paintings of the Paleolithic era, experts said. The dye is commonly associated with religious beliefs, such as in burials. The pit grave also contained a bowl and five bone blades of varying sizes. Photos show these bone tools, including a pointed funnel.

The tools immediately drew the attention of researchers, Piotr Osypiński, one of the excavations’ lead archaeologists, told Science in Poland. The tools were sharpened while preserving the original shape of the bone. Experts believe these tools were used for cattle bloodletting, the release said. The custom of bleeding cows is still practiced today by the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania, Osypiński said. For the Maasai people, cow’s blood is “both ordinary and sacred food,” Atlas Obscura reported, and is “considered beneficial for people with weakened immune systems” with its high amount of protein. The blood may be consumed by itself, mixed with milk or added in other cooked dishes. The process of cattle bleeding involves nicking the animal’s neck, collecting the blood in a bowl and then clotting the wound so it heals properly.

Archaeologists think the tools found at the Letti Basin cemetery may be the oldest evidence of this cultural practice, Osypiński said in the release. Researchers did not explain why the tools were buried at the cemetery. More bone blades were uncovered at another burial in the cemetery. This small oval burial had the remains of a young man curled in a fetal position. The deceased, with a small, precisely cut hole in his skull, was covered with an animal skin dyed in ochre. The hole in the man’s skull may have been related to his death, the release said. It’s unclear if this hole was cut as part of a surgical procedure or a religious practice.

Cattle bones were also unearthed from the cemetery, archaeologists said. The collection of graves has provided insight into the region’s ancient pastoral communities.Previous excavations at the Letti Basin found evidence that the region’s occupants domesticated cattle beginning 10,000 years ago, according to a June news release from Science in Poland. This challenged preexisting theories that domesticated cattle came to East Africa from Turkey and Iraq. The Letti Basin is along a horseshoe-shaped bend of the Nile River in northern Sudan. Nizeiza, a city located on the southernmost part of the basin, is about 215 miles northwest of Khartoum, the nation’s capital.

See Separate Article FIRST CATTLE AND COW DOMESTICATION factsanddetails.com

Predynastic Burials in Egypt

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “In ancient Egypt, the primary evidence for the Predynastic Period, principally the fourth millennium B.C., derives from burials. In Upper Egypt, there is a clear trend over the period towards greater investment in mortuary facilities and rituals, experimentation in body treatments, and increasing disparity in burial form and content between a small number of elite and a larger non-elite population. In Maadi/Buto contexts in Lower Egypt, pit burials remained simple with minimal differentiation and less of a focus upon display-orientated rituals [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

It was from Upper Egyptian cemetery sites such as Naqada and Ballas and el- Abadiya and Hiw that the Predynastic was first recognized and classified. Over 15,000 burials are documented for Upper Egypt, but less than 600 Maadi/Buto graves from Lower Egypt are known. From the content and form of these burials, the chronological framework of the fourth millennium B.C. has been constructed and the nature and development of social complexity during the rise of the state charted. There has been a particular focus upon aspects of wealth and status differentiation following the work of Hoffman. The clear trend identified in these studies, for Naqadan burials at least, is for a widening disparity between graves in terms of the effort invested in tomb construction (size and architecture) and in the provision of grave goods. Less attention has been paid to other aspects of social identities represented in burials, such as gender, age, and ethnicity, although recent excavations at Adaima, Hierakonpolis, and in the Delta are providing firmer foundations for more nuanced interpretations, together with a reassessment of early twentieth century excavations.

“In comparison to Neolithic fifth millennium B.C. ‘house burials’, interred in what are probably the abandoned parts of settlements at el-Omari and Merimde Beni-Salame, most graves known from the Badarian and fourth millennium B.C. are from cemeteries set apart from habitation. Nevertheless, in both Upper and Lower Egypt some interments, predominately those of children, are still found within settlements, sometimes within large ceramic vessels (‘pot-burials’). This may account, to some extent, for the under-representation of children within most cemeteries.”

See Separate Articles: EARLY PRE-DYNASTIC EGYPT (4500-4000 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Middle Paleolithoc tools from pharonic civilization, Nubian tools from Plos and Khormusan tools from Science Digest, el-Hosh rock art, Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation.

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024