Home | Category: Early Mesopotamia, the Fertile Crescent and Archaeology / Assyrians

ARCHAEOLOGY IN ASSYRIA

In in the mid 19th century British explorer-quasi-archaeologists began rummaging around what is now Iraq look for ruins and artifacts related to ancient cities mentioned in The Bible. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the nineteenth century, most of the Middle East belonged to the Turkish Ottoman empire. However, people independent of the central authorities in the capital Constantinople controlled much of the region. This made travel for Europeans in the area not only extremely difficult but often very dangerous. Nonetheless, merchants, diplomats, and adventurers occasionally journeyed into this land and returned with tantalizing tales of ancient ruins. Since most educated people in Europe were schooled in the Hebrew Bible and classical authors, they recognized that many of the sites in the Holy Land, and especially Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq), represented the remains of some of the oldest civilizations in the world. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Although the world of Assyria continues to be revealed through spectacular finds, none can match the dramatic, romantic discoveries of the earlier generation. Opportunities for Europeans to explore some of these ancient sites resulted from expanding political interests in the region by the empires of Britain and France following Napoleon's expedition to Egypt and Palestine and his defeat by British and Turkish forces. Some of the earliest archaeological research was carried out by Claudius Rich (1787–1820), British Resident in Baghdad from 1808 to 1820. The antiquities he gathered formed the basis for the Mesopotamian collections in the British Museum. It was a Frenchman, Paul-Émile Botta (1802–1870), however, who undertook the first major excavations.

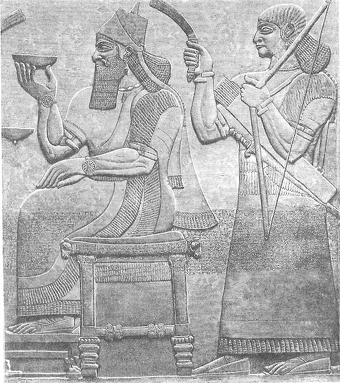

In 1842, Botta started digging at Nineveh in north Mesopotamia, but a lack of major discoveries led him to shift his attention to the site of Khorsabad. Here he discovered the palace of Sargon II, built around 710 B.C. The mud-brick walls of the palace had been lined with slabs of alabaster finely carved in relief depicting the king's triumphs. In addition, some of the palace gateways were guarded by massive stone colossi. In 1846, Botta shipped many of these enormous monuments to France.

A year before the reliefs from Khorsabad entered the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Englishman Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) had begun digging at the site of Nimrud (ancient Kalhu). Largely funded by the British Museum, he discovered the remains of many palaces of the ninth and eighth centuries B.C. built by kings over the 150 years when Nimrud was the capital of Assyria. After Layard had left for London in 1851, Rassam continued to dig at Nineveh. In 1853, he discovered the palace of Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.), which furnished the British Museum with some of the finest sculptured slabs. Meanwhile, the French worked at Khorsabad under Victor Place (1818–1875) until 1855. After that date, however, despite increased archaeological work in the region, no more large palaces with sculptured reliefs were discovered. Although the world of Assyria continues to be revealed through spectacular finds (for example, the discovery of royal tombs at Nimrud by Iraqi archaeologists in 1988–89), none can match the dramatic, romantic discoveries of the earlier generation.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Winged Bull: The Extraordinary Life of Henry Layard, the Adventurer Who Discovered the Lost City of Nineveh” by Jeff Pearce (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nineveh and Babylon” by Austen Henry Layard Amazon.com;

“Nimrud - An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed” by David Oates and Joan Oates (2001) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs” by Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, McGuire Gibson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud: Volume VI - Documents from the Nabu Temple and from Private Houses on the Citadel” by S Herbordt, R Mattila, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Land of Assur and the Yoke of Assur: Studies on Assyria 1971-2005" by J. Nicholas Postgate (2007) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Sir Austen Henry Layard

In 1844, Sir Austen Henry Layard, a British lawyer and pioneering archaeologist, began the first excavations of the Assyrian and Babylonian ruins in Nineveh and Nimrud. As a 28-year-old British diplomat stationed in Baghdad, he became convinced that a series of earth mounds along the Tigris River might be an ancient capita. He secretly hired Arab tribesmen to dig in the mounds and immediately found an ancient palace compound complete with murals, ivories and wall carvings. He assumed wrongly it was the ancient Biblical city of Nineveh

Layard discovered the remains of 9th and 7th century B.C. palaces and an immense statue of a winged bull. He had many of the things he excavated sent via camel, river raft and ship to London, where they are now on display in the British museum. He was knighted for his discoveries Back in Iraq Layard’s tools were stolen and he kidnaped a man to get them back. After Layard left, archaeologists descended on Nimrud and took everything the could find, including more extraordinary reliefs that are scattered around the globe in museums in Mumbai, Baghdad, London and New York.

Austen Henry Layard

Amy Davidson wrote in The New Yorker: Layard: “has extensive descriptions of local Yazidis in his book “Nineveh and Babylon,” published in 1849. (Yezidi girls, he says, wore a garment “like a Scotch plaid.”) Layard writes that parts of the winged bull were designed “with a spirit and truthfulness worthy of a Greek artist,” but that others were only roughly outlined, “as if the sculptors had been interrupted by some public calamity.” He brought one of the bulls to the British Museum. (There is another at the Metropolitan Museum, in New York.) [Source: Amy Davidson, The New Yorker , February 27, 2015]

Many of the actual discoveries were made by Hormuzd Rassam, an Iraqi archaeologist, who was friend and protege of Layard and who excavated Nineveh and Nimrud through the 19th century, making many great discoveries only to have the credit taken by Englishmen, whose acceptance and admiration he greatly craved.

Paul-Emile Botta, a French diplomat, worked in the Nineveh around the same time as Layard. Between them, Botta and Layard uncovered the remains of five Assyrian palaces. Many of Botta’s find are now in the Louvre. When monumental sculptures of winged bulls and bas-reliefs of Assyrian conquests were first displayed the British Museum in London and the Louvre in Paris, they drew huge crowds. “Nivenah and Its Remains”, Layard chronicle of his work, became a bestseller.

Discoveries by Sir Austen Henry Layard and Where They Ended Up

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Between 1845 and 1847, Layard, with the help of an assistant, Hormuzd Rassam (1826–1910), and hundreds of workers, revealed the huge mud-brick palace of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), the first such structure decorated with stone wall reliefs. He also excavated other royal buildings and temples at Nimrud, while at Nineveh Layard revealed a large section of perhaps the greatest Assyrian palace built by Sennacherib (r. 704–681 B.C.), where he discovered over two miles of sculptured slabs. After a break in London, Layard resumed excavations in 1849, leaving Mesopotamia for good in 1851. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

The majority of Layard's finds were sent to the British Museum, but several of the reliefs found their way to other institutions. Some were acquired by American missionaries working in Iraq who saw the carved slabs as evidence for biblical history. Other sculptures entered private collections such as that of the industrialist J. P. Morgan (six of which are now in the Metropolitan Museum). Layard himself sent some reliefs to the country home of his cousin at Canford Manor in Dorsetshire, England. There they were installed in the "Nineveh Porch," which had cast-iron doors featuring human-headed bull colossi, stained-glass windows composed of patterns drawn from wall paintings found at Nimrud, and a ceiling painted with cuneiform texts.

The collection of twenty-six Assyrian sculptures displayed on the walls was surpassed at the time only by the Assyrian relief collection in the British Museum. In 1919, eighteen of the sculptures were sold, and they eventually came into the collection of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who donated them to the Metropolitan Museum in 1932.

Agatha Christie at Ur, Nimrud and Nineveh

Agatha Christie and Max Mallowan

The English mystery writer Agatha Christie met archeologist, Max Mallowan, 15 years her junior, at an archaeological dig at Ur. Later they were married after Christie made Mallowan promise that he wouldn't play golf or run off with other women. The couple got on quite well. He liked "digging the dead." She wrote about "copses and stiffs.” He often took her on his expeditions to Egypt and the Near East. It was the second marriage for Christie. Her first was to an English army officer, Achier Christie, who she met when she was 22 and married in the middle of World War I. After Agatha became successful, Archie spent most of his time on the golf course. The marriage fell part when he confessed he loved another woman, Teresa Neele. They were divorced in 1928.

Christie caught the eye of Mallowan when she visited to Ur, They were married in 1930.. Michael Taylor wrote in Archaeological magazine, “ Katherine Woolley quickly came to detest Christie, who was subsequently banished from the dig. Mallowan lamented that "there was only room for one woman at Ur," and spent the first dig season after his marriage separated from his bride.”

Christie and Mallowan participated in the archaeological work at Ur and searched in vain for the lost city of Ukresh. Mallowan served as an assistant to Woolley between 1925 and 1930. Agatha Christie wrote her 1936 mystery “ Murder in Mesopotamia” based on her experiences in at Ur. In the novel an archaeologist's sickly wife, Mrs. Leidner, is brutally murdered. Similarities between the victim and Katherine Woolley are said to have been more than a coincidence.

Mallowan and Christie worked at the Assyrian sites of Nimrud and Nineveh in the 1950s. Amy Davidson wrote in The New Yorker: “Mallowan was the reason that Hercule Poirot, in one novel, visits Aleppo. (He was also the source for a classic Daily Mail headline: “British Museum buys 3,000-year-old ivory carvings Agatha Christie cleaned with her face cream.”) In her autobiography, in which she talks about the face cream, she writes about how “times in Baghdad were gradually worsening politically,” and so, for a few years, there were no new excavations in Iraq; instead, “everyone went to Syria.” [Source: Amy Davidson, The New Yorker , February 27, 2015]

Friezes from Nineveh and King Tiglath-Pileser III’s Palace

Layard excavated the site of a palace belonging to King Tiglath-Pileser III (reigned 744-727 B.C.) in the 19th century. The building had been dismantled by one his successors and the sculptured wall slabs had been neatly stacked in preparation for recarving that never took place. In the 1990s, many of the slabs were stolen and found their way to the international art market. Some sit in the British Museum, Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Iraq Museum.

American missionaries in the Middle East were particularly anxious to get their hands on them because they thought they proved the veracity of the Bible. Among these was Dr. Henri Byron Haskell, who sent five panels to his alma mater, Bowdoin, in the 1850s. These efforts marked the beginning of the historical study of the Bible and “awareness of the wider world of the Bible” and “the idea the Bible was historically accurate,::

Much of the stuff that Layard excavated from Nineveh, including a series of friezes called the Nineveh Marbles, was brought back to England. Some of it eventually found its way into the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Seventeen sculptures and friezes were given to one Lady Charlotte to decorate the Nineveh Porch in her estate, Canford Manor, in Dorset..

In 1923, Cranford Manor was sold and became the Cranford School, The Nivenah Porch became the school’s snack bar. In 1959, seven small reliefs were found and they ended up in museums in Jerusalem, London, Boston and Oxford. In 1992, a six-foot-long relief of an eunuch and a winged divine figure, from an Assyrian palace of the ninth century B.C. was found. It sold at Christie's in London for $11.9 million. The money was used build several new buildings at the school. It was purchased by Japanese dealer Noriyoshi Horiuchi for the Miho Museum in Japan.

Nimrud Treasure

In the 1989 and 1990, four tombs, dated to the 8th and 9th century, believed to belong to queens (or at least consorts) of Ashurnasipal II were excavated in a royal palace in Nimrud. One tomb alone contained over 28 kilograms of gold. The items are the among the most impressive examples of Assyrian art — or for that matter ancient gold — ever found.

Archaeologists found 40 kilograms of treasures and 157 objects, including a golden mesh diadem with tiger eye agate, lapis lazuli; a gold child's crown embellished with rosettes, grapes, vines and winged female deities; 14 armlets and arm band with cloisonne and turquoise; enameled and engraved gold jewelry; four anklets including, one gold anklet weighing a kilogram; 15 vessels, including one with scenes of hunting and warfare; 79 earnings; 30 rings; many chains; a palm crested plaque; gold bowls and flasks; a bracelet inlaid with semiprecious stones and held together with a pin; and rare electrum mirrors.

The jewelry was worn by royal consorts of Assyria's rulers, A finely worked gold necklace features clasp in the shape of entwined animal heads. A finely wrought gold crown is topped by delicate winged females. There also chains of tiny gold pomegranates and earrings with semi-precious stones.

In 1990, archaeologists discovered a royal Assyrian treasure buried in a palace well around the 8th century B.C. in Nimrud. Artifacts of gold and ivory were found on 400 skeletons, once shackled in irons around their wrists and ankles. Archaeologists have speculated that maybe the skeletons belonged to supporters of an executed king.

Discovery of the Nimrud Treasures

In 1988 Iraqi archaeologist Muzahem Hussein uncovered two 8th century B.C. tombs under the royal palace in Nimrud. He discovered the site when he realized he was standing on some great vaults while putting some bricks back in place After two weeks of clearing away dirt and debris he caught his first glimpse of gold.

The first tomb was still sealed and contained a woman who was 50 or so and a collection of beautiful jewelry and semiprecious stones. A second tomb, about 100 meters away, contained the two women, perhaps queens. They were placed in the same sarcophagus one on top of the other, wrapped in embroidered linen and covered with gold jewelry. One of the women had been dried and smoked at temperatures of 300 to 500 degrees, the first evidence of mummification-like practices in Mesopotamia.

The second tomb contained a curse, threatening the person who opened the grave of Queen Yaba (wife of powerful Tiglthpilese II (744-727 B.C.) with eternal thirst and restlessness, with a specific warning about placing another corpse inside. The curse was written before the second corpse was placed inside. The two women inside were 30 to 35 years of age, with the second being buried 20 to 50 year after the first. The first is thought to be Queen Yaba. The other is thought to be the person identified by a gold bowl found inside the sarcophagus that reads: “Atilia, queen of Sargon, king of Assyria: who rule from 721 ro 705 B.C."

A third tomb excavated in 1989 had been looted but looters missed an antechamber that contained three bronze coffins: 1) one with six people, a young adult, three children, a baby and a fetus." 2) another with a young woman, with a gold crown, thought to have been a queen; and 3) a third with a 55- to 60-year-old man, and a golden vessel that appears to have identified him as a powerful general that served under served several kings.

piece from the Nimrud Treasures

The treasure was on display for just a few months before the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when it was packed away for protection and put in a vault beneath Baghdad's central bank . Though the bank was bombed, burned and flooded during the 2003 invasion of Iraq the treasure reportedly was undamaged.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024