Home | Category: Education, Transportation and Health

INFRASTRUCTURE AND COMMUNICATIONS IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

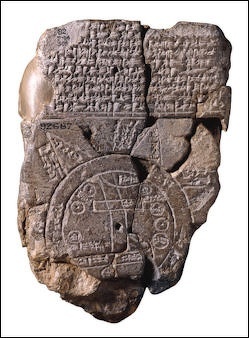

Babylonian map

First settlers organized into self-sufficient communities that cooperated with irrigation. Later organized labor built walls, temples, dwellings.

The Babylonians had a postal system. The Assyrians developed a more sophisticated one so that correspondence could be efficiently delivered throughout their vast empire.

The Assyrians built the first aqueducts and paved roads. Aqueducts provided water for lavish gardens that covered the size of football fields. Their extensive system of roads allowed them to dispatch their armies and supplies quickly to the far corners of their empire. See History

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

“Irrigation of Mesopotamia” by William Willcocks (1917) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia, the Gulf Region, and the Indus: Archaeological and Textual Evidence for Contact in the Third and Early Second Millennia B.C.” by Steffen Laursen and Piotr Steinkeller Amazon.com

“Domestic Animals of Mesopotamia” (2 vols.) -- BSA vols. 7-8

by Nicholas Postgate and Marvin Powell (1993) Amazon.com;

“Domestic Animals of Mesopotamia Part II (Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture, VIII) by unknown author Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

Cuneiform Tablet Postal Letters

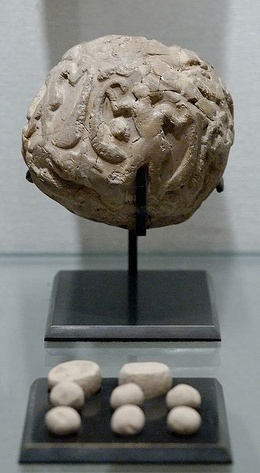

Cuneiform tablets were usually of small size and were sometimes sent as letters. The cuneiform system of writing allows a large number of words to be compressed into a small space, and the writing is generally so minute as to try the eyes of the modern decipherer. Fragments of clay had been found at Tello, bearing the impressions of seals belonging to the officials of Sargon of Akkad and his successor, and addressed to the viceroy of Lagas, to King Naram-Sin and other personages. They were, in fact, the envelopes of letters and despatches which passed between Lagas and Agadê, or Akkad, the capital of the dynasty. Sometimes, however, the clay fragment has the form of a ball, and must then have been attached by a string to the missive like the seals of mediæval deeds. In either case the seal of the functionary from whom the missive came was imprinted upon it as well as the address of the person for whom it was intended.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

That the clay tablet should ever have been used for epistolary purposes seems strange to us who are accustomed to paper and envelopes. But it occupied no more space than many modern official letters, and was lighter to carry than most of the packages that pass through the parcelpost. Now and then it was enveloped in an outer covering of clay, on which the address and the chief contents of it were noted; but the public were usually prevented from knowing what it contained in another way. Before it was handed over to the messenger or postman it was “sealed,” which generally appears to mean that it was deposited in some receptacle, perhaps of leather or linen, which was then tied up and sealed. In fact,

On a letter written around 1800 B.C., Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine: The tablet would have dried in the sun near the parents’ home in the Assyrian city of Assur, on the banks of the Tigris River in modern Iraq, before being wrapped in a thin cloth and placed in a clay envelope. As was done with much Assyrian correspondence, one or both of Zizizi’s parents would have taken a stone cylinder that hung from a cord around their neck and rolled it across the envelope’s surface, creating a ribbonlike impression or seal. Her mother’s seal depicts tall deerlike figures with long horns standing upright, each one leaning on a staff. This seal was unique to Ishtar-bashti and functioned like an ID, signaling to Zizizi that the letter was indeed from her mother.[Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

Ancient Mesopotamian Postal Service

Thousands of letters seem to have passed to and fro in this manner, making it clear that the postal service of Babylonia was already well organized in the time of Sargon and NaramSin. The Tel-el-Amarna letters show that in the fifteenth century before our era a similar postal service was established throughout the Eastern world, from the banks of the Euphrates to those of the Nile. To what an antiquity it reached back it is at present impossible to say. At all events, when Hammurabi was King, letters were frequent and common among the educated classes of the population. Most of those which have been preserved are from private individuals to one another. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

On how a letter was sent around 1800 B.C., Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine: Next, the tablet was packed on a donkey caravan and transported for six weeks across 750 miles of A tablet bearing an irate letter from the Assyrian merchant Imdi-ilum and his wife, Ishtar-bashti, was found in the archive of their daughter Zizizi, who lived in Kanesh. Syrian steppe, southeastern Turkey’s Taurus Mountains, and, finally, the Anatolian plains to Kanesh, where Zizizi had launched a career as a successful moneylender. There, Zizizi, who had settled into her new life but perhaps still missed her parents, filed away the tablet in a private archive in her home. [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

Babylonian and Assyrian letters were treated much as ours are when they are put into a post-bag to which the seals of the postoffice are attached. There were excellent roads all over Western Asia, with post-stations at intervals where relays of horses could be procured. Along these all letters to or from the King and the government were carried by royal messengers. It is probable that the letters of private individuals were also carried by the same hands. The letters of Tel-el-Amarna give us some idea of the wide extension of the postal system and the ease with which letters were constantly being conveyed from one part of the East to another.

The foreign correspondence of the Pharaoh was carried on with Babylonia and Assyria in the east, Mesopotamia and Cappadocia in the north, and Palestine and Syria in the west. The civilized and Oriental world was thus bound together by a network of postal routes over which literary intercourse was perpetually passing. They extended from the Euphrates to the Nile and from the plateau of Asia Minor to the confines of Arabia. These routes followed the old lines of war and trade along which armies had marched and merchants had travelled for unnumbered generations. The Tel-el-Amarna tablets show us that letter-writing was not confined to Assyria and Babylonia on the one hand, or to Egypt on the other. Wherever the ancient culture of Babylonia had spread, there had gone with it not only the cuneiform characters and the use of clay as a writing material, but the art of letter-writing as well.

Roads in Mesopotamia

Satellite imagery had been used to map ancient roads throughout Mesopotamia, including a network or roads between Nineveh and Tell Brak, an ancient site near Aleppo, Syria. Some of the roads were more than 400 feet wide. The images show where the road were. Shallow depressions were left by heavy animal traffic when they were used. This harden the surface and caused the roadway to sink, leaving behind troughs that retained moisture and helped plants grow. The satellite images picked up the subtle changes in growth.

Mesopotamia was where some of the first great trade routes were established. "Control of the Euphrates," an Italian archaeologist Paolo Matthiae told National Geographic, "meant control over the strategic traffic in metals from Anatolia and in wood from the Syrian forests near the Mediterranean, both natural resources essential to Mesopotamian economic life." The only goods available in abundance in Mesopotamia were mud, clay, reeds, palm, fish, and grain. To obtain other goods Mesopotamians needed to trade. Mesopotamians developed large scale trade. Ships brought in goods from distant lands. Labor and grain were exported. Metals were brought in overland routes and paid for with wool and grains. Goods were moved in jars and clay pots. Seals identified who they belonged to.

The Sumerians established trade links with cultures in Anatolia, Syria, Persia and the Indus Valley. Similarities between pottery in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley indicate that trade probably occurred between the two regions. During the reign of the pharaoh Pepi I (2332 to 2283 B.C.) Egypt traded with Mesopotamian cities as far north as Ebla in Syria near the border of present-day Turkey.

Bridges and Tolls in Ancient Mesopotamia

Sippara lay on both sides of the Euphrates, like Babylon, and its two halves were probably connected by a pontoon-bridge, as we know was the case at Babylon. Tolls were levied for passing over the latter, and probably also for passing under it in boats. At all events a document translated by Mr. Pinches shows that the quay-duties were paid into the same department of the government as the tolls derived from the bridge.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The document, which is dated in the twenty-sixth year of Darius, is so interesting that it may be quoted in full: “The revenue derived from the bridge and the quays, and the guard-house, which is under the control of Guzanu, the captain of Babylon, of which Sirku, the son of Iddinâ, has charge, besides the amount derived from the tolls levied at the bridge of Guzanu, the captain of Babylon, of which Muranu, the son of Nebo-kin-abli, and Nebo-bullidhsu, the son of Guzanu, have charge: Kharitsanu and Iqubu (Jacob) and Nergal-ibni are the watchmen of the bridge. Sirku, the son of Iddinâ, the son of Egibi, and Muranu, the son of Nebo-kin-abli, the son of the watchman of the pontoon, have paid to Bel-asûa, the son of Nergal-yubal-lidh, the son of Mudammiq-Rimmon, and Ubaru, the son of Bel-akhi-erba, the son of the watchman of the pontoon, as dues for a month, 15 shekels of white silver, in one-shekel pieces and coined. Bel-asûa and Ubaru shall guard the ships which are moored under the bridge. Muranu and his trustees, Bel-asûa and Ubaru, shall not pay the money derived from the tolls levied at the bridge, which is due each month from Sirku in the absence of the latter. All the traffic over the bridge shall be reported by Bel-asûa and Ubaru to Sirku and the watchmen of the bridge.”

Oil in Ancient Mesopotamia

bitumen boat model The Mesopotamians used asphalt to as a building material 5000 years ago and were thus the first people to use petroleum. Archaeologists have found evidence that bituminous deposits were being exploited in the Near East as early as 3000 B.C. Methods for stabilizing crudes and tars so they weren't dangerous was developed at a very early time.

The first references to oil were made on cuneiform tablets in Babylonia in 2000 B.C. It was referred to as “ naptu” , which means "that which flares up." Mesopotamians were fascinated by naphtha especially since fire created with it could not be put out with water. Naptu was used in construction, road building, waterproofing, skin ointments and cements. One cuneiform tablet from that era read: "If a certain place in the land “ naptu” oozes out, that country will walk in widowhood. If the water of a river bears...oil, want will seize on the peoples." Another states: "May donkey urine be your drink, “naptu” your ointment."

Evidence from cuneiform tablets indicates that petroleum products were used for torches, lamps, mortars, pigments, textile finishes, magic fire tricks, medicines, and incendiary weapons. One tablet read: "If a certain place in the land “ naptu” oozes out, that country will walk in widowhood. If the water of a river bears...oil, want will seize on the peoples." Another states: "May donkey urine be your drink, “ naptu” your ointment." Naptu was used as a skin ointment.

Oil in Iraq may have been the “burning fiery furnace” of King Nebuchadnezzar described in The Bible. In the 1st century B.C., the Greek historian Diodorus wrote: "of all the marvels of Babylonia the most amazing is the mass of asphalt produced there...Uncountable numbers of people have drawn from it, as far from some vast spring, yet the supply remains intact."

Petroleum in the Ancient World

In the 5th century B.C. Herodotus described a famous spot in Persia where oil oozed from the ground. He wrote that a man with a wineskin "makes a dip with this, draws the liquid up, and then pours it over the receptacle, from there it passes into another, where it turns into three different shapes; the salt and the asphalt solidify while they collect on clay containers."

In ancient times oil came primarily from seepage. No one thought of drilling for in the ground until the 19th century. In the 1st century B.C., the Greek historian Diodorus wrote: "of all the marvels of Babylonia the most amazing is the mass of asphalt produced there...Uncountable numbers of people have drawn from it, as from some vast spring, yet the supply remains intact."

Romans burned petroleum in the their lamps instead of olive oil. The Byzantines used naptha for their Greek Fire weapons. In the 1st century A.D., the Greek geographer Strabo wrote: "if naphtha is brought near a flame, it catches fire, and if you smear some on the body and come near a flame, the body will catch fire. It cannot be quenched with water — it just burns harder — unless a whole lot is used, but it can be smothered and quenched with mud, vinegar, alum or birdlime."

Hittites and Oil

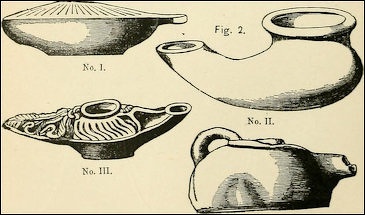

Near Eastern lamps

Harry A. Hoffner, Jr wrote in “Oil in Hittite Texts”: “Oil was one of the minimal essentials in ancient Near Eastern life. This has been noted in connection with ancient Israel, but it is also true in Hittite Anatolia. That being the case, oil is included among the elementary needs of the poor which compassionate people are enjoined to meet. Several texts whose composition goes back to the Old Hittite period mention this: to the hungry give bread, to the thirsty water, to the naked clothes, to the dried out/desiccated. The same situation is reflected in a passage from the new Hurro-Hittite bilingual, where the god Teshub is poor and must be helped by his fellow deities. They give food to the hungry god, clothes to the naked god, and oil to the hurtant- god. [Source: Harry A. Hoffner, Jr., “Oil in Hittite Texts,” Internet Archive, from Emory/Biblical Archaeology /=/]

“Oil in Hittite texts can be from an animal or a vegetable source. Oil from plants includes olive oil, sesame oil, cypress (or juniper) oil/resin, and oil extracted from nuts. Oil from animals includes lard (i.e., oil/fat from pigs) and sheep fat. Güterbock enumerated the various oil-bearing plants known to the Hittites, which included the olive, sesame, and several plants which are probably nuts. /=/

“Sheep fat or tallow, is placed in or on a KUSkursa-, which has been interpreted as either a "hunting bag" or a "fleece," which in turn is suspended from an evergreen eya-tree as a symbol of the prosperity given by the gods. That Ì.UDU was a solid substance is also clear from the fact that it is used alongside wax to make magic figurines. The purpose of making the figurines out of wax and sheep tallow is that they will represent evil and will be destroyed in the course of the subsequent ritual. The exact manner of destroying the symbols is unclear. The verb in the ritual text is arha sallanu-, which probably means "to melt down". /=/

See Separate Article: HITTITE LIFE, FOOD, OIL, WATER AND POTTERY africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024