Home | Category: Economic, Agriculture and Trade

BUSINESS IN MESOPOTAMIA

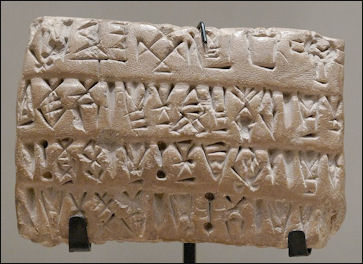

Economic tablet from Susa In spite of its agricultural basis and the vast army of slaves with which it was filled, Babylonia was essentially a land of trades and manufactures. Its manufacturing fame was remembered into classical days. Organized production of handcrafted goods was first developed in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians produced manufactured goods. The weaving of wool by thousands of workers is regarded as the for large-scale industry.

The Sumerians a developed sense of ownership and private property. It seems like many business transactions were recorded and the minutest amounts and smallest quantities were listed. Contracts were sealed with cylinder seals that were rolled over clay to produce a relief image.

There wasn't much in Ur and other cities in Mesopotamia except water from the Euphrates River and mud brick made from the dry earth. Prized materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian all were imported.

See Naptu, Oil

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Kanesh: A Merchant Colony in Bronze Age Anatolia” by Mogens Trolle Larsen (2015) Amazon.com;

“Women of Assur and Kanesh: Texts from the Archives of Assyrian Merchants” by Cécile Michel (2020) Amazon.com

“Trade and Finance in Ancient Mesopotamia” by J. G. Dercksen (1999) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Kings, and Merchants in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia by D Charpin (2015) Amazon.com;

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society in Northern Babylonia (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta)

by A Goddeeris (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Woe; a Study of the Origin of Certain Banking Practices and of Their Effect on the Events of Ancient History Written in the Light of the Present Day” by David Astle | (1975) Amazon.com;

“Ledgers and Prices: Early Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts” by Daniel C. Snell (1982) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East” by Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, Robert K. Englund (Author), Amazon.com;

“Selected Business Documents On the Neo-Babylonian Period” by Ungnad Arthur (2022) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Rental Houses in the Neo-Babylonian Period (VI-V Centuries BC)” by Stefan Zawadzki (2018) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Market Areas of Babylon and Nineveh

In front of the city gate of Babylon was an open space, the rébit, such as may still be seen at the entrance to an Oriental town, and which was used as a market-place. The rébit of Nineveh lay on the north side of the city, in the direction where Sargon built his palace, the ruins of which are now known as Khorsabad. But besides the market-place outside the walls there were also open spaces inside them where markets could be held and sheep and cattle sold. Babylon, it would seem, was full of such public “squares,” and so, too, was Nineveh. The suqi or “streets” led into them, long, narrow lanes through which a chariot or cart could be driven with difficulty. Here and there, however, there were streets of a broader and better character, called suli, which originally denoted the raised and paved ascents which led to a temple. It was along these that the religious processions were conducted, and the King and his generals passed over them in triumph after a victory. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

One of these main streets, called Â-ibursabu, intersected Babylon; it was constructed of brick by Nebuchadnezzar, paved with large slabs of stone, and raised to a considerable height. It started from the principal gate of the city, and after passing Ê-Saggil, the great temple of Bel-Marduk, was carried as far as the sanctuary of Ishtar. When Assur-bani-pal's army captured Babylon, after a long siege, the “mercy-seats” of the gods and the paved roads were “cleansed” by order of the Assyrian King and the advice of “the prophets,” while the ordinary streets and lanes were left to themselves.

It was in these latter streets, however, that the shops and bazaars were situated. Here the trade of the country was carried on in shops which possessed no windows, but were sheltered from the sun by awnings that were stretched across the street. Behind the shops were magazines and store-houses, as well as the rooms in which the larger industries, like that of weaving, were carried on. The scavengers of the streets were probably dogs. As early as the time of Hammurabi, however, there were officers termed rabiani, whose duty it was to look after “the city, the walls, and the streets.” The streets, moreover, had separate names. Here and there “beer-houses” were to be found, answering to the public- houses of to-day, as well as regular inns. The beer-houses are not infrequently alluded to in the texts, and a deed relating to the purchase of a house in Sippara, of the age of Hammurabi, mentions one that was in a sort of underground cellar, like some of the beer-houses of modern Germany.

Textile Industry and Business in Babylonia

One of the rooms in the palace of Nero was hung with Babylonian tapestries, which had cost four millions of sesterces, or more than £32,000, and Cato, it is said, sold a Babylonian mantle because it was too costly and splendid for a Roman to wear. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The wool of which the cloths and rugs of Babylonia were made was derived from the flocks which fed on the banks of the Euphrates, and a large body of artisans was employed in weaving it into tapestries and curtains, robes and carpets. They were woven in bright and vari-colored patterns; the figures of men and animals were depicted upon them and the bas-relief or fresco could be replaced upon the wall by a picture in tapestry. The dyes were mainly vegetable, though the kermes or cochineal-insect, out of which the precious scarlet dye was extracted, was brought from the neighborhood of the Indus. So at least Ktesias states in the age of the Persian empire; and since teak was found by Mr. Taylor among the ruins of Ur, it is probable that intercourse with the western coast of India went back to an early date.

Indeed an old bilingual list of clothing gives sindhu as the name of a material which is explained to be “vegetable wool;” in this we must see the cotton which in the classical epoch was imported from the island of Tylos, in the Persian Gulf, but which, as its name declares, must have originally been “the Indian” plant. The looms and weavers of Babylonia are, as is natural, repeatedly referred to in the contracts, many of which, moreover, relate to the sale and purchase of wool.

One of them even shows us Belshazzar, the son and heir-apparent of the King Nabonidos, as a wool-merchant on a considerable scale. “The sum of 20 manehs for wool,” it says, “the property of Belshazzar, the son of the king, which has been handed over to Iddin-Marduk, the son of Basa, the son of Nur-Sin, through the agency of Nebo-zabit, the servant of the house of Belshazzar, the son of the king, and the secretaries of the son of the king. In the month Adar (February) of the eleventh year (of Nabonidos) the debtor shall pay the money, 20 manehs. The house of — — the Persian and all the property of Iddin-Marduk in town and country shall be the security of Belshazzar, the son of the king, until he shall pay in full the money aforesaid. The money which shall (meanwhile) accrue upon (the wool) he shall pay as interest.” Then follow the names of five witnesses and a priest, as well as the date and the place of registration. This was Babylon, and the priest, Bel-akhi-iddin, who helped to witness the deed was a brother of Nabonidos and consequently the uncle of Belshazzar.

The weight of the wool that was sold is unfortunately not stated. But considering that 20 manehs, or £180, was paid for it, there must have been a considerable amount of it. In the reign of Cambyses the amount of wool needed for the robe of the image of the Sun-goddess  was as much as 5 manehs 5 shekels in weight.

Sheep and Wool Business Contracts in Ancient Mesopotamia

We may gather from a contract dated the 5th of Sivan in the eighteenth year of Darius that it was not customary to pay for any sheep that were sold until they had been driven into the city, the cost of doing so being included in the price. The contract is as follows: “One hundred sheep of the house of Akhabtum, the mother of Sa-Bel-iddin, the servant of Bel-sunu, that have been sold to La-Bel, the son of Khabdiya, on the 10th day of the month Ab in the eighteenth year of Darius the king: The sheep, 200 in number, must be brought into Babylon and delivered to Supêsu, the servant of Sa-Bel-iddin. If 15 manehs of silver are not paid for the sheep on the 10th of Ab, they must be paid on 20th of the month. If the money, amounting to 15 manehs, is not paid, then interest shall be paid according to this agreement at the rate of one shekel for each maneh per month.” Then come the names of eight witnesses and a priest, the date, and the place of registration, which was a town called Tsikhu.

The contract is interesting from several points of view. The sheep, it will be seen, belonged to a woman, and not to her son, who was “the servant” of a Babylonian gentleman and had another “servant” who acted as his agent at Babylon. The father of the purchaser of the sheep bears the Hebrew name of 'Abdî, which is transcribed into Babylonian in the usual fashion, and the name of the purchaser himself, which may be translated “(There is) no Bel,” may imply that he was a Jew.

Akhabtum and her son were doubtless Arameans, and it is noticeable that the latter is termed a “servant” and not a “slave.” Before entering the city an octroi duty had to be paid upon the sheep as upon other produce of the country. The custom-house was at the gate, and the duty is accordingly called “gate-money” in the contracts. In front of the gate was an open space, the rébit, such as may still be seen at the entrance to an Oriental town, and which was used as a market-place.

Partnerships and Companies in Ancient Mesopotamia

Trade partnerships were common, and even commercial companies were not unknown. The great banking and moneylending firm which was known in Babylonia under the name of its founder, Egibi, and from which so many of the contract-tablets have been derived, was an example of the latter. It lasted through several generations and seems to have been but little affected by the political revolutions and changes which took place at Babylon. It saw the rise and fall of the empire of Nebuchadnezzar, and flourished quite as much under the Persian as under the native kings. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The partners usually contributed in equal parts to the business, and the profits were divided equally among them. Where this was not the case, provision was made for a proportionate distribution of profit and loss. All profits were included, whether made, to use the language of Babylonian law, “in town or country.” The partnership was generally entered into for a fixed term of years, but could be terminated sooner by death or by agreement. One of the partners could be represented by an agent, who was often a slave; in some instances we hear of the wife taking the place of her husband or other relation during his absence from home. Thus in a deed dated in the second year of Nergal-sharezer (559 B.C.) we read: “As long as Pani-Nebo-dhemi, the brother of Ili-qanua, does not return from his travels, Burasu, the wife of Ili-qanua, shall share in the business of Ili-qanua, in the place of Pani-Nebo-dhemi. When Pani-Nebo-dhemi returns she shall leave Ili-qanua and hand over the share to Pani-Nebo-dhemi.” As one of the witnesses to the document is a “minister of the king” who bears the Syrian name of Salammanu, or Solomon the son of Baal-tammuh, it is possible that Pani-Nebo-dhemi was a Syrian merchant whose business obliged him to reside in a foreign country.

In the later Babylonian period the report of a trial dated the eighth day of Sebat or January, in the eighteenth year of Nebuchadnezzar II., we have the following reference to one that had been made twenty-one years before: “A partnership was entered into between Nebo-yukin-abla and his son Nebo-bel-sunu on the one side and Musezib-Bel on the other, which lasted from the eighteenth year of Nabopolassar, King of Babylon, to the eighteenth year of Nebuchadnezzar. The contract was produced before the judge of the judges. Fifty shekels of silver were adjudged to Nebo-bel-sunu and his father Nebo-yukin-abla. No further agreement or partnership exists between the two parties.… They have ended their contract with one another. All former obligations in their names are rescinded.”

One of the latest Babylonian deeds of partnership that have come down to us is dated in the fifth year of Xerxes. It begins with the statement that “Bel-edheru, son of Nergal-edheru and Ribâta, son of Kasmani, have entered into partnership with one another, contributing severally toward it 2½ manehs of silver in stamped shekel-pieces and half a maneh of silver, also in stamped shekel-pieces. Whatever profits Ribâta shall make on the capital — namely, the 3 manehs in stamped shekel-pieces — whether in town or country, [he shall divide with] Bel-edheru proportionally to the share of the latter in the business. When the partnership is dissolved he shall repay to Bel-edheru the [2½] manehs contributed by him. Ribâta, son of Kasmani, undertakes all responsibility for the money.” Then come the names of six witnesses.

Money, however, was not the only subject of a deed of partnership. Houses and other property could be bought and sold and traded with in common. Thus we hear of Itti-Marduk-baladh, the grandson of “the Egyptian,” and Marduk-sapik-zeri starting as partners with a capital of 5 manehs of silver and 130 empty barrels, two slaves acting as agents, and on another occasion we find it stipulated that “200 barrels full of good beer, 20 empty barrels, 10 cups and saucers, 90 gur of dates in the storehouse, 15 gur of chickpease (?), and 14 sheep, besides the profits from the shop and whatever else Bel-sunu has accumulated, shall be shared between him” and his partner.

3,900-Year-Old Assyrian Business Family

The Kanesh tablets from Turkey have been dated to 1900 B.C. They contain many letters between members of merchant families. Assyriologist Cécile Michel of the French National Center for Scientific Research has studied tablets found Kanesh in depth, Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine, In her view many of the tablets record the inside workings of some of the world’s first multinational family businesses. “The father is the head, the sons settle in Anatolia to trade, and the women are part of the organization, producing textiles,” she says. “All these international trade networks rely on family relationships — they have to trust people.”

Each branch of the family network was financially independent. Individual assets were managed separately, even between married couples. Husbands sent proceeds from their wives’ textile sales back to Assur, as well as gold and silver to cover household expenses and the cost of producing more bolts of cloth. Many of the Kanesh tablets document small loans of silver between household members, which were paid back with interest.

A wealthy businesswoman in Assur named Taram-Kubi sent a series of letters to her husband in Kanesh, a merchant named Innaya. She regularly updated him on a lawsuit he faced in Assur over an irregularity in the sale of lapis lazuli, a semiprecious deep-blue stone that was imported from mines in what is now northeastern Afghanistan. “The cases have been deferred,” she wrote. “Do not be impatient; reinforce your witnesses, certify your tablets, and send them to me by the next caravan.”

Assyrian and Babylonian Business Women

Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine Through their 3,900-year-old letters, it becomes clear that the women of Assur acted as business partners to their husbands, fathers, and brothers, sometimes debating profit margins and strategizing over which types of textiles would perform best in the marketplace. “The thin textile you sent me, make more like it and send them to me,” a trader named Puzur-Assur wrote to a woman named Waqqurtum, with whom he had an unknown relationship. .[Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

In the letter, a copy of which he kept in his private archive in Kanesh, Puzur-Assur gave Waqqurtum several tips to improve her sales, based on what he was seeing sell well in the markets of Anatolia. “They should strike one side of the textile, and not pluck it. Its warp should be close,” he insisted. If she couldn’t produce thin textiles, he suggested that she buy them from the markets in Assur and send those instead, lowering her profits, but probably boosting her sales. It’s likely that Waqqurtum was related in some way to Puzur-Assur

In their correspondence, Taram-Kubi and her husband quarreled frequently over money. When Innaya complained about his wife’s spending habits and her lavish lifestyle, Taram-Kubi accused him of clearing the household of its grain stores on a recent visit to Assur. After his departure, she wrote, a famine swept the city, leaving her without barley to feed their children. She insisted that her husband send silver to help her buy food — which he appears to have done. In another tablet, she expressed how much she missed him. “When you hear this letter, come, look to Ashur, your god, and your home hearth, and let me see you in person while I am still alive!” she wrote. “The beer bread I made for you has become too old.”

As far back as the reign of Samsu-iluna we find women entering into partnership with men for business purposes on a footing of absolute equality. A certain Amat-Samas, for instance, a devotee of the Sun-god, did so with two men in order to trade with a maneh of silver which had been borrowed from the treasury of the god. It was stipulated in the deed which was indentured when the partnership was made that in case of disagreement the capital and interest accruing from it were to be divided in equal shares among the three partners. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

That the women in the Amorite settlements enjoyed the same freedom and powers as the women of Babylonia is shown by two documents, one dated in the reign of the second King of the dynasty to which Hammurabi belonged, the other in the reign of Hammurabi's great-grandfather. In the first, Kuryatum, the daughter of an Amorite, receives a field of more than four acres of which she had been wrongfully deprived; in the second, the same Kuryatum and her brother Sumu-rah are sued by the three children of an Amorite, one of whom is a woman, for the recovery of a field, house, slaves, and date-palms. The case was brought before “the judges of Bit-Samas,” “the Temple of the (Babylonian) Sun-god,” who rejected the claim. At a very early period of Babylonian history the Syrian god Hadad, or Rimmon, had been, as it were, domesticated in Babylonia, where he was known as Amurru, “the Amorite.” He had come with the Amorite merchants and settlers, and was naturally their patron-deity. His wife, Asratu, or Asherah, was called, by the Sumerians, Nin-Marki, “the mistress of the Amorite land,” and was identified with their own Gubarra. Nin-Marki, or Asherah, presided over the Syrian settlements, the part of the city where the foreigners resided being under her protection like the gate which led to “the district of the Amorites” beyond the walls.

3,770-Year-Old Business Complaint from Mesopotamia

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Among the thousands of Mesopotamian tablets containing both official and personal letters, one example stands out as the first recorded customer complaint and evidence of a business relationship gone very sour. Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Nanni expressed his extreme displeasure to the merchant Ea-nasir about a recent copper shipment:“When you came, you said to me as follows: “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots that were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!” What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt....Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.

Erin Blakemore wrote in National Geographic: The notorious tablet was discovered in Ur about a century ago, when an expedition led by famed archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley unearthed why may be the home of Ea-nā ir, including a slew of business documents recorded in cuneiform writing. Nanni’s complaint dates to 1750 B.C. The palm-sized tablet is inscribed in Akkadian, the language spoken in ancient Mesopotamia at the time. Today, the tablet is part of the collections of the British Museum.[Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, October 17, 2023]

The letter, dictated by Nanni, slams Ea-nā ir for promising “fine quality copper ingots,” then failing to follow through on the deal. Instead, Nanni complains, the merchant has sent low-grade copper, treated him and his messenger with contempt, and taken his money — seemingly because Nanni owes him “one (trifling) mina of silver.” (A mina was the equivalent of approximately one-fifth of an ounce.) When Nanni’s messenger attempted to dispute the quality of the copper with Ea-nā ir, Nanni claims, he was dismissed: “If you want to take them, take them,” Ea-nā ir reportedly said. “If you do not want to take them, go away!”

Nanni is livid, both about the low-quality copper and the merchant’s treatment of his assitant. “I will not accept here any copper from you that is not fine quality,” he angrily concludes, according to one translator. “I shall…select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.”In another translation, Nanni warns that “Because you despised me, I shall inflict grief on you!”

As it turns out, Nanni wasn’t the only one with a complaint against the merchant; in fact, the British Museum has even more evidence of Ea-nā ir’s crooked copper dealings. On another tablet, someone named Imgur-Sin exhorts Ea-nā ir to “transfer good copper to Niga-Nanna…Give him good copper, so that I will not become upset! Do you not know that I am weary?” The copper baron’s reputation for inferior product had obviously gotten around Ur: In yet another communique to the copper baron, a trader named Nar-am demands: “Give [Igmil-Sin, Nar-am’s messenger] very good copper! Hopefully the copper in your care has not gone out.”

But given the durability of Ea-nā ir’s customer service problem, perhaps it’s only fair to give him the last word. Remarkably, a note from the beleaguered Babylonian merchant survives — and unsurprisingly, it’s full of copper-caused drama. In the letter, Ea-nā ir tells a man named Šumum-libši and a coppersmith not to overreact when two other men come to them in search of some missing metal. “Do not be critical,” advises Ea-nā ir. “Do not fear!”

Moneylenders and Banks in Ancient Babylonia

Among the professions of ancient Babylonia, moneylending held a foremost place. It was, in fact, one of the most lucrative of professions, and was followed by all classes of the population, the highest as well the lowest. Members of the royal family did not disdain to lend money at high rates of interest, receiving as security for it various kinds of property. It is true that in such cases the business was managed by an agent; but the lender of the money, and not the agent, was legally responsible for all the consequences of his action, and it was to him that all the profits went. The moneylender was the banker of antiquity. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In a trading community like that of Babylonia, where actual coin was comparatively scarce, and the gigantic system of credit which prevails in the modern world had not as yet come into existence, it was impossible to do without him. The taxes had to be paid in cash, which was required by the government for the payment of a standing army, and a large body of officials. The same causes which have thrown the fellahin of modern Egypt into the hands of Greek usurers were at work in ancient Babylonia.

In some instances the moneylender founded a business which lasted for a number of generations and brought a large part of the property of the country into the possession of the firm. This was notably the case with the great firm of Egibi, established at Babylon before the time of Sennacherib, which in the age of the Babylonian empire and Persian conquest became the Rothschilds of the ancient world. It lent money to the state as well as to individuals, it undertook agencies for private persons, and eventually absorbed a good deal of what was properly attorney's business. Deeds and other legal documents belonging to others as well as to members of the firm were lodged for security in its record-chambers, stored in the great earthenware jars which served as safes. The larger part of the contract-tablets from which our knowledge of the social life of later Babylonia is derived has come from the offices of the firm.

The Egibi firm was not the only great banking or trading establishment of which we know in ancient Babylonia. The American excavators at Niffer have brought to light the records of another firm, that of Murasu, which, although established in a provincial town and not in the capital, rose to a position of great wealth and influence under the Persian kings Artaxerxes I. (464-424 B.C.) and Darius II. (424-405 B.C.).

The tablets found at Tello also indicate the existence of similarly important trading firms in the Babylonia of 2700 B.C., though at this period trade was chiefly confined to home products, cattle and sheep, wool and grain, dates and bitumen. The learned professions were well represented.

Did Modern Banking Began in Ancient Babylonian Temples?

In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia gold, silver and other valuables were deposited in temples for safe-keeping. The history of banks can be traced to ancient Babylonian temples in the early 2nd millennium B.C.. In Babylon at the time of Hammurabi, there are records of loans made by the priests of the temple. Temples took in donations and tax revenue and amassed great wealth. Then, they redistributed these goods to people in need such as widows, orphans, and the poor. [Source: MessageTo Eagle March 7, 2016 Ancient History Facts]

After a thousand years, the priests who ran the temples had so much money that the concept of banking came up as an idea. Around the time of Hammurabi, in the 18th century B.C., the priests allowed people to take loans. Old Babylonian temples made numerous loans to poor and entrepreneurs in need. Among many other things, the Code of Hammurabi recorded interest-bearing loans.”

The text on a cuneiform tablet detailing a loan of silver, c. 1800 B.C., reads: “3 1/3 silver sigloi, at interest of 1/6 sigloi and 6 grains per sigloi, has Amurritum, servant of Ikun-pi-Istar, received on loan from Ilum-nasir. In the third month she shall pay the silver.” 1 sigloi=8.3 grams.

The loans were made at reduced below-market interest rates, lower than those offered on loans given by private individuals, and sometimes arrangements were made for the creditor to make food donations to the temple instead of repaying interest. Cuneiform records of the house of Egibi of Babylonia describe the families financial activities dated as having occurred sometime after 1000 B.C. and ending sometime during the reign of Darius I, show a “lending house” a family engaging in “professional banking.”

Loans in Ancient Mesopotamia

In the early days of Babylonia the interest upon a loan was paid in kind. But the introduction of a circulating medium goes back to an ancient date, and it was not long before payment in grain or other crops was replaced by its equivalent in cash. Already before the days of Amraphel and Abraham, we find contracts stipulating for the payment of so many silver shekels per month upon each maneh lent to the borrower. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Thus we have one written in Semitic-Babylonian which reads: “Kis-nunu, the son of Imur-Sin, has received one maneh and a half of silver from Zikilum, on which he will pay 12 shekels of silver (a month). The capital and interest are to be paid on the day of the harvest as guaranteed. Dated the year when Immerum dug the Asukhi canal.” Then follow the names of three witnesses. The obligation to repay the loan on “the day of the harvest” is a survival from the time when all payments were in kind, and the creditor had a right to the first-fruits of the debtor's property.

A contract dated in the reign of Hammurabi, or Amraphel, similarly stipulates that interest on a loan made to a certain Arad-ilisu by one of the female devotees of the Sun-god, should be paid into the treasury of the temple of Samas “on the day of the harvest.” The interest was reckoned at so much a month, as in the East to-day; originally it had to be paid at the end of each month, according to the literal terms of the agreement, but as time went on it became usual to reserve the payment to the end of six months or a year. It was only where the debtor was not considered trustworthy or the security was insufficient that the literal interpretation of the agreement was insisted on.

Full security was taken for a loan, and the contract relating to it was attested by a number of witnesses. Thus the following contract was drawn up in the third year of Nabonidos, a loan of a maneh of silver having been made by one of the members of the Egibi firm to a man and his wife: “One maneh of silver, the property of Nadin-Marduk, the son of Iqisa-bel, the son of Nur-sin, has been received by Nebo-baladan, the son of Nadin-sumi, and Bau-ed-herat, the daughter of Samas-ebus. In the month Tisri (September) they shall repay the money and the interest upon it. Their upper field, which adjoins that of Sum-yukin, the son of Sa-Nebo-sû, as well as the lower field, which forms the boundary of the house of the Seer, and is planted with palm-trees and grass, is the security of Nadin-Marduk, to which (in case of insolvency) he shall have the first claim. No other creditor shall take possession of it until Nadin-Marduk has received in full the capital and interest. In the month Tisri the dates which are then ripe upon the palms shall be valued, and according to the current price of them at the time in the town of Sakhrin, Nadin-Marduk shall accept them instead of interest at the rate of thirty-six qas (fifty quarts) the shekel (3s.). The money is intended to pay the tax for providing the soldiers of the king of Babylon with arms.

Differing Interest Rates in Ancient Mesopotamia

The rate of interest, as was natural, tended to be lower with the lapse of time and the growth of wealth. In the age of the Babylonian empire and the Persian conquest the normal rate was, however, still as high as 1 shekel a month upon each maneh, or twenty per cent. But we have a contract dated in the fifth year of Nebuchadnezzar in which a talent of silver is lent, and the interest charged upon it is not more than half a shekel per month on the maneh, or ten per cent. Three years later, in another contract, the rate of interest is stated to be five-sixths of a shekel, or sixteen and two-thirds per cent, while in the fifteenth year of Samas-sum-yukin the interest upon a loan of 16 shekels is only a quarter of a shekel. At this time Babylonia was suffering from the results of its revolt from Assyria, which may explain the lowness of the rate of interest. At all events, six years earlier, Remut, one of the members of the Egibi firm, lent a sum of money to a man and his wife without charging any interest at all upon it, and stipulating only that the money should be repaid when the land was again prosperous. At times, however, money was lent upon the understanding that interest would be charged upon it only if it were not repaid by a specified date.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Thus in the ninth year of Samas-sum-yukin half a maneh was lent by Suma to Tukubenu on the fourth of Marchesvan, or October, upon which no interest was to be paid up to the end of the following Tisri, or September, which corresponded with “the day of the harvest” of the older contracts; but after that, if the money were still unpaid, interest at the rate of half a shekel a month, or ten per cent., would be charged. At other times the interest was paid by the year, as with us, and not by the month; in this case it was at a lower rate than the normal twenty per cent. In the fourteenth year of Nabopolassar, for example, a maneh of silver was lent at the rate of 7 shekels on each maneh per annum — that is to say, at eleven and two-thirds per cent. — and under Nebuchadnezzar money was borrowed at annual interest of 8 shekels for each maneh, or thirteen and one-third per cent.

Witnessed by Nebo-bel-sunu, the son of Bau-akhi, the son of Dahik; Nebo-dîni-ebus, the son of Kinenunâ; Nebo-zira-usabsi, the son, Samas-ibni Bazuzu, the son of Samas-ibni; Marduk-erba, the son of Nadin; and the scribe Bel-iddin, the son of Bel-yupakhkhir, the son of Dabibu. Dated at Sakhrinni, the 28th day of Iyyar (April), the third year of Nabonidos, King of Babylon.” In Assyria the rate of interest was a good deal higher than it was in Babylonia. It is true that in a contract dated 667 B.C., one of the parties to which was the son of the secretary of the municipality of Dur-Sargon, the modern Khorsabad, it is twenty per cent., as in Babylonia, but this is almost the only case in which it is so.

Elsewhere, in deeds dated 684 B.C., 656, and later, the rate is as much as twenty-five per cent., while in one instance — a deed dated 711 B.C. — it rises to thirty-three and a third per cent. Among the witnesses to the last-mentioned deed are two “smiths,” one of whom is described as a “coppersmith,” and the other bears the Armenian name of Sihduri or Sarduris. The money is usually reckoned according to the standard of Carchemish. That the rate of interest should have been higher in Assyria than in Babylonia is not surprising. Commerce was less developed there, and the attention of the population was devoted rather to war and agriculture than to trade.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024