Home | Category: Economic, Agriculture and Trade

LABOR IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

There were two main classes of free workmen, the skilled artisan and the agricultural laborer. The agricultural character of ancient Mesopotamia, and the fact that so many of the peasantry possessed land of their own, prevented the agriculturist from sinking into that condition of serfdom and degradation which the existence of slavery would otherwise have brought about. Moreover, the flocks and cattle were tended by Bedouin and Arameans, who were proud of their freedom and independence, like the Bedouin of modern Egypt. In spite, therefore, of the fact that so much of the labor of the country was performed by slaves, agriculture was in high esteem and the free agriculturist was held in honor. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

As ancient Mesopotamia developed and evolved, agriculture became more advanced, surpluses were generated, freeing farmers to perform other jobs. Over time former farmers could earn enough to specialize in certain tasks and become what would qualify as craftsmen. Workers were often paid with barley. Under the Cod of Hammurabi, maximum prices and minimum wages were fixed by decree and the terms for apprenticeships were defined.

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: “Despite the multitude of slaves, hired labour was often needed, especially at harvest. This was matter of contract, and the hirer, who usually paid in advance, might demand a guarantee to fulfil the engagement. Cattle were hired for ploughing, working the watering-machines, carting, threshing, etc. The Code fixed a statutory wage for sowers, ox-drivers, field-labourers, and hire for oxen, asses, etc.[Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911]

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence”

by P. R. S. Moorey (1999) Amazon.com;

“Lithic Technology of Neolithic Syria” (BAR Archaeopress) by Yoshihiro Nishiaki (2000) Amazon.com;

“II Workshop on Late Neolithic Ceramics in Ancient Mesopotamia: Pottery in Context”

by Anna Gómez Bach, Jörg Becker, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pottery from Tell Khaiber: A Craft Tradition of the First Sealand Dynasty: 1" (Archaeology of Ancient Iraq) by Daniel Calderbank (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Competition of Fibres: Early Textile Production in Western Asia, Southeast and Central Europe (10,000–500 BC)” by Dr. Wolfram Schier and Prof. Dr Susan Pollock (2020) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Tools, Textiles and Contexts: Investigating Textile Production in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age” by Eva Andersson Strand and Marie-Louise Nosch (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Textiles: Production, Crafts and Society” by Marie-Louise Nosch, C. Gillis (2007) Amazon.com;

“First Textiles: The Beginnings of Textile Production in Europe and the Mediterranean” by Małgorzata Siennicka, Lorenz Rahmstorf, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Jobs in Ancient Mesopotamia

Tablets listed scores of professions. Trades during Mesopotamian times included tradesmen, butchers, stonemasons, water carriers, fishermen, estate workers, farmers, tanners, weavers, boatbuilders, furniture makers, bakers, silversmiths, metal workers, pottery makers, beer brewers, bread makers, leatherworkers, spinners, weavers, clothes makers, tool and weapons makers, jewelers, woodworkers and people in charge of preparing sacrifices and maintaining buildings.

There were also many civil servants. One of the highest positions was the scribe, who worked closely with the king and the bureaucracy, recording events and tallying up commodities. In ancient Mesopotamia, writing — and also reading — was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties.

Pottery making is a very old craft. There was more to it than just making containers, pots, vases and jugs. The walls of the palaces and temples of Babylonia and Assyria were adorned with glazed and enamelled tiles on which figures and other designs were drawn in brilliant colors; they were then covered with a metallic glaze and fired. Babylonia, in fact, seems to have been the original home of the enamelled tile and therewith of the manufacture of porcelain. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

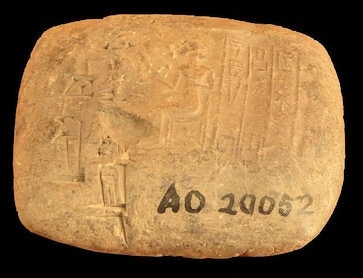

Gem-cutting and seal-making were a highly developed skills. The seal-cylinder of Ibni-sarru, the librarian of Sargon of Akkad, which is now in a private collection in Paris, is one of the most beautiful specimens of the art that has ever been produced. The pebble was cut in a cylindrical shape, and various figures were engraved upon it. The favorite design was that of a god or goddess to whom the owner of the seal is being introduced by a priest; sometimes the King takes the place of the deity, at other times it is the adventures of Gilgamesh, the hero of the great Chaldean Epic, that are represented upon the stone. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 253-260: Farm Labor

Daily salary from Sumer

253) If any one agree with another to tend his field, give him seed, entrust a yoke of oxen to him, and bind him to cultivate the field, if he steal the corn or plants, and take them for himself, his hands shall be hewn off. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

254) If he take the seed-corn for himself, and do not use the yoke of oxen, he shall compensate him for the amount of the seed-corn.

255) If he sublet the man's yoke of oxen or steal the seed-corn, planting nothing in the field, he shall be convicted, and for each one hundred gan he shall pay sixty gur of corn.

256) If his community will not pay for him, then he shall be placed in that field with the cattle (at work).

257) If any one hire a field laborer, he shall pay him eight gur of corn per year.

258) If any one hire an ox-driver, he shall pay him six gur of corn per year.

259) If any one steal a water-wheel from the field, he shall pay five shekels in money to its owner.

260) If any one steal a shadduf (used to draw water from the river or canal) or a plow, he shall pay three shekels in money.

Labor Contracts from Mesopotamia in 2200 B.C.

Contract for Hire of Laborer, Reign of Shamshu-Iluna, c. 2200 B.C.: This is a contract from the reign of Shamshu-iluna of the Akkadian dynasty, c. 2200 B.C. It is of many of like character. “Mar-Sippar has hired for one year Marduk-nasir, son of Alabbana, from Munapirtu, his mother. He will pay as wages for one year two and a half shekels of silver. She has received one half shekel of silver, one se [1/180th of a shekel], out of a year's wages.” [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]

Contract for Production of a Coat of Mail, Thirty-Fourth year of Darius, 488 B.C.: This tablet is dated in the thirty-fourth year Darius I (488 B. C.), and was regarded as an imporant transaction, since it is signed by four witnesses and a scribe. “One coat of mail, insignum of power which will protect, is to be made by the woman Mupagalgagitum, daughter of Qarikhiya, for Shamash-iddin, son of Rimut. She will deliver in the month Shebat one coat of mail, which is to be made and which will protect.”

Contract of Warranty for Setting of a Gold Ring, Thirty-fifth year of Artaxerxes, 429 B.C.: The transaction needs no comment. The wealthy representative of the house of Murashu obtained from the firm of jewellers which sold him the ring a guarantee that the setting would last for twenty years; if it does not, they are to forfeit ten manas. “Bel-akha-iddin and Bel-shunu, sons of Bel-___ and Khatin, son of Bazuzu, spoke unto Bel-shum-iddin, son of Murashu, saying: "As to the ring in which an emerald has been set in gold, we guarantee that for twenty years the emerald will not fall from the gold ring. If the emerald falls from the gold ring before the expiration of twenty years, Bel-akha-iddin, Bel-shunu (and) Khatin will pay to Bel-shum-iddin ten manas of silver. (The names of seven witnesses and a scribe are appended. The date is) Nippur, Elul eighth, the thirty-fifth year of Artaxerxes.”

Provision of Materials for Workers in Ancient Mesopotamia

Employment contract from Ur The workman was supplied with his materials by the customer, and received only the value of his labor. What this was can be gathered from a receipt dated the 11th day of Chisleu, in the fourteenth year of Nabonidos, recording the payment of 4 shekels to “the ironsmith,” Suqâ, for making certain objects out of 3 manehs of iron which had been handed over to him. The cost of bricks and reeds has already been described. Bitumen was more valuable. In the fourteenth year of Nabonidos a contract was made to supply five hundred loads of it for 50 shekels, while at the same time the wooden handle of an ax was estimated at one shekel. Five years previously only 2 shekels had been given for three hundred wooden handles, but they were doubtless intended for knives.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In the sixth year of Nabonidos the grandson of the priest of Sippara undertook to supply “bricks, reeds, beams, doors, and chopped straw for building the house of Rimut” for 12 manehs of silver, or £108. The wages of the workmen were not included in the contract. With these prices it is instructive to compare those recorded on contract tablets of the age of the third dynasty of Ur, which preceded that under which Abraham was born.

These tablets, though very numerous, have as yet been but little examined, and the system of weights and measures which they contain is still but imperfectly known. We learn from them that bitumen could be purchased at the time at the rate of half a shekel of silver for each talent of 60 manehs, and that logs of wood imported from abroad were sold at the rate of eight, ten, twelve, and sixty logs a shekel, the price varying according to the nature of the wood. Prices, however, as might be expected, are usually calculated in grain, oil, and the like, and the exact relation of these to the shekel and maneh has still to be determined.

Wages for Workers in Ancient Mesopotamia

The average wages of the workmen can be more easily fixed. Contracts dated in the reign of Hammurabi, the Amraphel of Genesis, and found at Sippara, show that it was at the rate of about 4 shekels a year, the laborer's food being usually thrown in as well. Thus in one of these contracts we read: “Rimmon-bani has hired Sumi-izzitim for his brother, as a laborer, for three months, his wages to be one shekel and a half of silver, three measures of flour, and 1 qa and a half of oil. There shall be no withdrawal from the agreement. Ibni-amurru and Sikni-Anunit have endorsed it. Rimmon-bani has hired the laborer in the presence of Abum-ilu (Abimael), the son of Ibni-samas, of Ili-su-ibni, the son of Igas-Rimmon; and Arad-Bel, the son of Akhuwam.” Then follows the 7 date. Another contract of the same age is of much the same tenor. “NurRimmon has taken Idiyatum, the son of Ili-kamma, from Naram-bani, to work for him for a year at a yearly wage of 4½ shekels of silver. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

At the beginning of the month Sebat, Idiyatum shall enter upon his service, and in the month Iyyar it shall come to an end and he shall quit it. Witnessed by Beltani, the daughter of Araz-za; by Beltani, the daughter of Mudadum; by Amat-Samas, the daughter of Asarid-ili; by Arad-izzitim, the son of Samas-mutasi; and by Amat-Bau, the priestess (?); the year when the Temple of the Abundance of Rimmon (was built by Hammurabi).” It will be noticed that with one exception the witnesses to this document are all women. There was but little rise in wages in subsequent centuries. A butcher was paid only 1 shekel for a month's work in the third year of Cambyses, as has been noticed above, and even skilled labor was not much better remunerated.

In the first year of Cambyses, for instance, only half a shekel was paid for painting the stucco of a wall, though in the same year 67 shekels (£10 1s.) were given to a seal-cutter for a month's labor. Slavery prevented wages from rising by flooding the labor market, and the free artisan had to compete with a vast body of slaves. Hence it was that unskilled work was still so commonly paid in kind rather than in coin, and that the workman was content if his employer provided him with food. Thus in the second year of Nabonidos we are told that the “coppersmith,” Libludh, received 7 qas (about 8½ quarts) of flour for overlaying a chariot with copper, and in the seventeenth year of the same reign half a shekel of silver and 1 gur of wheat from the royal storehouse were paid to five men who had brought a flock of sheep to the King's administrator in the city of Ruzabu. The following laconic letter also tells the same tale: “Letter from Tabik-zeri to Gula-ibni, my brother. Give 54 qas of meal to the men who have dug the canal. The 9th of Nisan, fifth year of Cyrus, King of Eridu, King of the World.” The employer had a right to the workman's labor so long as he furnished him with food and clothing.

Guilds and Apprenticeships in Ancient Mesopotamia

The various trades formed guilds or corporations, and those who wished to enter one of these had to be apprenticed for a fixed number of years in order to learn the craft. As we have seen, slaves could be thus apprenticed by their owners and in this way become members of a guild. What the exact relation was between the slave and the free members of a trading guild we do not know, but it is probable that the slave was regarded as the representative of his master or mistress, who accordingly became, instead of himself, the real member of the corporation. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

We perhaps have a parallel in modern England, where a person can be elected a member of one of the “city companies,” or trade guilds, without being in any way connected with the trade himself. Since women in Babylonia were able to carry on a business, there would be no obstacle to a slave being apprenticed to a trade by his mistress. Hence it is that we find a Babylonian lady named Nubtâ, in the second year of Cyrus, apprenticing a slave to a weaver for five years. Nubtâ engaged to provide the apprentice with clothing and 1 qa (nearly 2 quarts) of grain each day. As in ancient Greece a quart of grain was considered a sufficient daily allowance for a man, the slave's allowance would seem to have been ample. The teacher was to be heavily fined if he failed to teach the trade, or overworked the apprentice and so made him unable to learn it, the fine being fixed at 6 qas (about 10 quarts) per diem. Any infringement of the contract on either side was further to be visited with a penalty of 30 shekels of silver. As 30 shekels of silver were equivalent to £4 10s., 6 qas of wheat at the time when the contract was drawn up would have cost about 1s. 3d.

Under Nebuchadnezzar we find 12 qas, or the third part of an ardeb, of sesame sold for half a shekel, which would make the cost of a single quart a little more than a penny. In the twelfth year of Nabonidos 60 shekels, or £9, were paid for 6 gur of sesame, and since the gur contained 5 ardebs, according to Dr. Oppert's calculation, the quart of sesame would have been a little less than 1½d. When we come to the reign of Cambyses we hear of 6½ shekels being paid for 2 ardebs, or about 100 quarts, of wheat; that would give 2½d. as the approximate value of a single qa. It would therefore have cost Nubtâ about 2½d. a day to feed a slave.

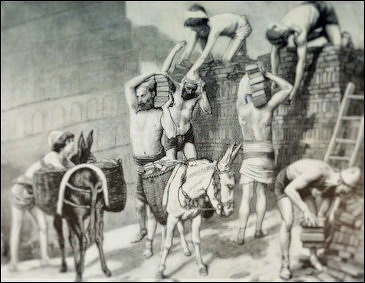

Brick-makers and Tablet-makers in Ancient Mesopotamia

Our enumeration of Babylonian trades would not be complete without mention being made of that of the brick-maker. The manufacture of bricks was indeed one of the chief industries of the country, and the brick-maker took the position which would be taken by the mason elsewhere. He erected all the buildings of Babylonia. The walls of the temples themselves were of brick. Even in Assyria the slavish imitation of Babylonian models caused brick to remain the chief building material of a kingdom where stone was plentiful and clay comparatively scarce. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The brick-yards stood on the outskirts of the cities, where the ground was low and where a thick bed of reeds grew in a pond or marsh. These reeds were an important requisite for the brick-maker's art; when dried they formed a bed on which the bricks rested while they were being baked by the sun; cut into small pieces they were mixed with the clay in order to bind it together; and if the bricks were burnt in a kiln the reeds were used as fuel. They were accordingly artificially cultivated, and fetched high prices.

Thus, in the fourteenth year of Nabonidos, we hear of 2 shekels being given for 200 bundles of reeds for building a bridge across a canal, and a shekel for 100 bundles to be made into torches. At the same time 55 shekels were paid for 8,000 loads of brick. The possession of a bed of reeds added to the value of an estate, and it is, therefore, always specified in deeds relating to the sale of property. One, situated at Sippara, was owned by a scribe, Arad-Bel, who has drawn up several contracts, as we learn incidentally from a document dated in the seventh year of Cyrus, in which Ardi, the grandson of “the brick-maker,” agrees to pay two-thirds of the bricks he makes to Arad-Bel, on condition of being allowed to manufacture them in the reed-bed of the latter. This is described as adjoining “the reed-bed of Bel-baladan and the plantation of the Sun-god.”

The brick-maker was also a potter, and the manifold products of the potter's skill, for which Babylonia was celebrated, were manufactured in the corner of the brick-field. Here also were made the tablets, which were handed to the professional scribe or the ordinary citizen to be written upon, and so take the place of the papyrus of ancient Egypt or the paper of to-day. The brick-maker was thus not only a potter, but the provider of literary materials as well. He might even be compared with the printer of the modern world, since texts were occasionally cut in wood and so impressed upon moulds of clay, which, after being hardened, were used as stamps, by means of which the texts could be multiplied, impressions of them being mechanically reproduced on other tablets or cylinders of clay.

Carpenters in Ancient Mesopotamia

The carpenter's trade is another handicraft to which there is frequent allusion in the texts. Already, before the days of Sargon of Akkad, beams of wood were fetched from distant lands for the temples and palaces of Chaldea. Cedar was brought from the mountains of Amanus and Lebanon, and other trees from Elam. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The palm could be used for purely architectural purposes, for boarding the crude bricks of the walls together, or to serve as the rafters of the roof, but it was unsuitable for doors or for the wooden panels with which the chambers of the temple or palace were often lined. For such purposes the cedar was considered best, and burnt panels of it have been found in the sanctuary of Ingurisa at Tello. Down to the latest days panels of wood were valuable in Babylonia, and we find it stipulated in the leases of houses that the lessee shall be allowed to remove the doors he has put up at his own expense.

But the carpenter's trade was not confined to inartistic work. From the earliest age of Babylonian history he was skilled in making household furniture, which was often of a highly artistic description. On a seal- cylinder, now in the British Museum, the King is represented as seated on a chair which, like those of ancient Egypt, rested on the feet of oxen, and similarly artistic couches and chests, inlaid with ivory or gold, were often to be met with in the houses of the rich.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024