Home | Category: Government and Legal System

HOW THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN JUSTICE SYSTEM WORKED

In Mesopotamia there were legal codes but no lawyers. Parties involved in disputes had to plead their cases directly to government authorities, often people close to the king or the king himself. All legal decisions and agreements were ratified by an oath taken before the gods and subject to their wrath or punishment if the agreement was broken.

Morris Jastrow said: Courts appear “to have been ordinarily composed of three judges, as among the Jews (whose method of legal procedure was largely modelled upon Babylonian prototypes). All the documents in the case had to be brought into court, and each party was obliged to bring witnesses to support any claims lying outside the record. The impression that one receives from a study of these decisions is that they were rendered after a careful and impartial consideration of the documents, and of the statements of the parties and of previous decisions. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: “In case of dispute the judges dealt first with the contract. They might not sustain it, but if the parties did not dispute it, they were free to observe it. The judges' decision might, however, be appealed against. Many contracts contain the proviso that in case of future dispute the parties would abide by "the decision of the king." The Hammurabi Code made known, in a vast number of cases, what that decision would be, and many cases of appeal to the king were sent back to the judges with orders to decide in accordance with it. The Code itself was carefully and logically arranged and the order of its sections was conditioned by their subject-matter. Nevertheless the order is not that of modern scientific treatises, and a somewhat different order from both is most convenient for our purpose. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911]

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: It is often difficult also to assess the degree to which usages and procedures observed in the private documents represent true and fast "rules" or at least established custom; they may represent nothing more than the momentary whims of kings and officials without having the status of fixed rules or precedents. This condition contrasts with the formal legal corpora, which at least pretend to represent rules designed for application in all like cases and conditions, and which certainly represent the consensus on ideal moral and legal practice within the societies for which they were propounded. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor” by Martha T. Roth (1997) Amazon.com;

br> “Early Mesopotamian Law” by Russ VerSteeg (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Code of Hammurabi” by Hammurabi Amazon.com;

“King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography” by Marc Van De Mieroop Amazon.com;

“Hammurabi of Babylon” by Dominique Charpin Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Court Procedure” by Shalom E. Holtz (2009) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Trial Records” by Shalom E. Holtz (2015) Amazon.com;

“Judicial Decisions in the Ancient Near East” by Sophie Démare-Lafont and Daniel E. Fleming (2023) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Dispute Documents in the British Museum (Dubsar)” by Malgorzata Sandowicz (2019) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Rental Houses in the Neo-Babylonian Period (VI-V Centuries BC)” by Stefan Zawadzki (2018) Amazon.com;

Pleas, Witnesses, Oaths and Appeals in the Mesopotamia Legal System

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: “Throughout the Code respect is paid to status. Suspicion was not enough. The criminal must be taken in the act, e.g. the adulterer, ravisher, etc. A man could not be convicted of theft unless the goods were found in his possession. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

“In the case of a lawsuit the plaintiff preferred his own plea. There is no trace of professional advocates, but the plea had to be in writing and the notary doubtless assisted in the drafting of it. The judge saw the plea, called the other parties before him and sent for the witnesses. If these were not at hand he might adjourn the case for their production, specifying a time up to six months. Guarantees might be entered into to produce the witnesses on a fixed day. The more important cases, especially those involving life and death, were tried by a bench of judges. With the judges were associated a body of elders, who shared in the decision, but whose exact function is not yet clear. Agreements, declarations and non-contentious cases are usually witnessed by one judge and twelve elders.

“Parties and witnesses were put on oath. The penalty for the false witness was usually that which would have been awarded the convicted criminal. In matters beyond the knowledge of men, as the guilt or innocence of an alleged wizard or a suspected wife, the ordeal by water was used. The accused jumped into the sacred river, and the innocent swam while the guilty drowned. The accused could clear himself by oath where his own knowledge was alone available. The plaintiff could swear to his loss by brigands, as to goods claimed, the price paid for a slave purchased abroad or the sum due to him. But great stress was laid on the production of written evidence. It was a serious thing to lose a document. The judges might be satisfied of its existence and terms by the evidence of the witnesses to it, and then issue an order that whenever found it should be given up. Contracts annulled were ordered to be broken. The court might go a journey to view the property and even take with them the sacred symbols on which oath was made.

“The decision given was embodied in writing, sealed and witnessed by the judges, the elders, witnesses and a scribe. Women might act in all these capacities. The parties swore an oath, embodied in the document, to observe its stipulations. Each took a copy and one was held by the scribe to be stored in the archives.

“Appeal to the king was allowed and is well attested. The judges at Babylon seem to have formed a superior court to those of provincial towns, but a defendant might elect to answer the charge before the local court and refuse to plead at Babylon. Finally, it may be noted that many immoral acts, such as the use of false weights, lying, etc., which could not be brought into court, are severely denounced in the Omen Tablets as likely to bring the offender into "the hand of God" as opposed to "the hand of the king."

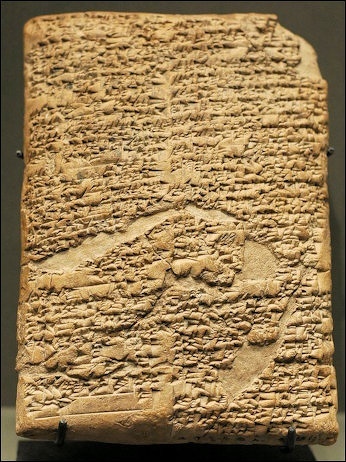

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 1-8: Basic Legal Stuff

The Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) is credited with producing the Code of Hammurabi, the oldest surviving set of laws. Recognized for putting eye for an eye justice into writing and remarkable for its depth and judiciousness, it consists of 282 case laws with legal procedures and penalties. Many of the laws had been around before the code was etched in the eight-foot-highin black diorite stone that bears them. Hammurabi codified them into a fixed and standardized set of laws.

1) If any one ensnare another, putting a ban upon him, but he can not prove it, then he that ensnared him shall be put to death. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

Prologue of Hammurabi's Code

2) If any one bring an accusation against a man, and the accused go to the river and leap into the river, if he sink in the river his accuser shall take possession of his house. But if the river prove that the accused is not guilty, and he escape unhurt, then he who had brought the accusation shall be put to death, while he who leaped into the river shall take possession of the house that had belonged to his accuser.

3) If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death.

4) If he satisfy the elders to impose a fine of grain or money, he shall receive the fine that the action produces.

5) If a judge try a case, reach a decision, and present his judgment in writing; if later error shall appear in his decision, and it be through his own fault, then he shall pay twelve times the fine set by him in the case, and he shall be publicly removed from the judge's bench, and never again shall he sit there to render judgement.

6) If any one steal the property of a temple or of the court, he shall be put to death, and also the one who receives the stolen thing from him shall be put to death.

7) If any one buy from the son or the slave of another man, without witnesses or a contract, silver or gold, a male or female slave, an ox or a sheep, an ass or anything, or if he take it in charge, he is considered a thief and shall be put to death.

8) If any one steal cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belong to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirtyfold therefor; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death.

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 9-12: Witnesses

9) If any one lose an article, and find it in the possession of another: if the person in whose possession the thing is found say "A merchant sold it to me, I paid for it before witnesses," and if the owner of the thing say, "I will bring witnesses who know my property," then shall the purchaser bring the merchant who sold it to him, and the witnesses before whom he bought it, and the owner shall bring witnesses who can identify his property. The judge shall examine their testimony — both of the witnesses before whom the price was paid, and of the witnesses who identify the lost article on oath. The merchant is then proved to be a thief and shall be put to death. The owner of the lost article receives his property, and he who bought it receives the money he paid from the estate of the merchant. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

10) If the purchaser does not bring the merchant and the witnesses before whom he bought the article, but its owner bring witnesses who identify it, then the buyer is the thief and shall be put to death, and the owner receives the lost article.

11) If the owner do not bring witnesses to identify the lost article, he is an evil-doer, he has traduced, and shall be put to death.

12) If the witnesses be not at hand, then shall the judge set a limit, at the expiration of six months) If his witnesses have not appeared within the six months, he is an evil-doer, and shall bear the fine of the pending case. [editor's note: there is no 13th law in the code, 13 being considered and unlucky and evil number]

Court Proceedings in Babylonia

Plaintiff and defendant pleaded their own causes, which were drawn up in legal form by the clerks of the court. Witnesses were called and examined and oaths were taken in the names of the gods and of the King. The King, it must be remembered, was in earlier times himself a god. In later days the oaths were usually dropped, and the evidence alone considered sufficient. Perhaps experience had taught the bench that perjury was not a preventable crime. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Each case was tried by a select number of judges, who were especially appointed to inquire into it, as we may gather from a document dated at Babylon the 6th day of Nisan in the seventeenth year of Nebuchadnezzar. “[These are] the judges,” it runs, “before whom Sapik-zeri, the son of Zirutu, [and] Baladhu, the son of Nasikatum, the servant of the secretary of the Marshlands, have appeared in their suit regarding a house. The house and deed had been duly sealed by Zirutu, the father of Sapik-zeri, and given to Baladhu. Baladhu, however, had come to terms with Sapikzeri and handed the house over to him and had taken the deed (from the record-office) and had given it to Sapik-zeri. Nebo-edher-napisti, the prefect of the Marshlands; Nebo-suzzizanni, the sub-prefect of the Marshlands; Marduk-erba, the mayor of Erech; Imbi-ilu, the priest of Ur, Bel-yuballidh, the son of Marduk-sum-ibni, the prefect of the western bank; Abtâ, the son of Suzubu, the son of Babutu; Musezib-Bel, the son of Nadin-akhi, the son of the adopted one; Baniya, the son of Abtâ, the priest of the temple of Sadu-rabu; and Sa-mas-ibni, the priest of Sadu-rabu.”

The list of judges shows that the civil governors could act as judges and that the priests were also eligible for the post. Neither the one class nor the other, however, is usually named, and we must conclude, therefore, that, though the governor of a province or the mayor of a town had a right to sit on the judicial bench, he did not often avail himself of it. The charge was drawn up in the technical form and attested by witnesses before it was presented to the court.

Court Cases in Babylonian

scene from the Life of King Nebuchadnezzar

We have an example of this dated at Sippara, the 28th day of Adar in the eighth year of Cyrus as King of Babylon: “Nebo-akhi-bullidh, the son of Su — , the governor of Sakhrin, on the 28th of Adar, the eighth year of Cyrus, king of Babylon and of the world, has brought the following charge against Bel-yuballidh, the priest of Sippara: I have taken Nanâ-iddin, son of Bau-eres, into my house because I am your father's brother and the governor of the city. Why, then, have you lifted up your hand against me? Rimmon-sar-uzur, the son of Nebo-yusezib; Nargiya and Erba, his brothers; Kutkah-ilu, the son of Bau-eres; Bel-yuballidh, the son of Barachiel; Bel-akhi-uzur, the son of Rimmon-yusallim; and Iqisa-abbu, the son of Samas-sar-uzur, have committed a crime by breaking through my door, entering into my house, and leaving it again after carrying away a maneh of silver.” Then come the names of five witnesses and the clerk. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

A suit might be compromised by the litigants before it came into court. In the reign of Nebuchadnezzar a certain Imliya brought witnesses to the door of the house of an official called Bel-iddin, and accused Arrali, the superintendent of the works, of having stolen an overcoat and a loin- cloth belonging to himself. But it was agreed that there would be no need on the part of the plaintiff to summon witnesses; the stolen goods were returned without recourse to the law. The care taken not to convict without sufficient evidence, and the thoroughness with which each case was investigated, is one of the most striking features in the records of the Babylonian lawsuits which have come down to us.

Two cases which were pleaded before the courts in the reign of Nabonidos illustrate the carefulness with which the evidence was examined. One of them was a case of false witness. Beli-litu, the daughter of Bel-yusezib, the wine merchant (?), “gave the following testimony before the judges of Nabonidos, king of Babylon: In the month Ab, the first year of Nergal-sharezer, king of Babylon, I sold my slave Bazuzu for thirty-five shekels of silver to Nebo-akhi-iddin, the son of Sula of the family of Egibi, but he now asserts that I owed him a debt and so has not paid me the money. The judges heard the charge, and caused Nebo-akhi-iddin to be summoned and to appear before them. Nebo-akhi-iddin produced the contract which he had made with Beli-litu; he proved that she had received the money, and convinced the judges. And Ziriya, Nebo-suma-lisir, and Edillu gave further testimony before the judges that Beli-litu, their mother, had received the silver.” The judges deliberated and condemned Beli-litu to a fine of 55 shekels, the highest fine that could be inflicted on her, and then gave it to Neboakhi-iddin. It is possible that the prejudice which has always existed against the money-lender may have encouraged Beli-litu to commit her act of dishonesty and perjury. That the judges should have handed over the fine to the defendant, instead of paying it to the court or putting it into their own pockets, is somewhat remarkable in the history of law.

The second case is that of some Syrians who had settled in Babylonia and there been naturalized. The official abstract of it is as follows: “Bunanitum, the daughter of the Kharisian, brought the following complaint before the judges of Nabonidos, king of Babylon: Ben-Hadadnathan, the son of Nikbaduh, married me and received three and onehalf manehs of silver as my dowry, and I bore him a daughter. I and Ben- Hadad-nathan, my husband, traded with the money of my dowry, and we bought together a house standing on eight roods of ground, in the district on the west side of the Euphrates in the suburb of Borsippa, for nine and one-third manehs of silver, as well as an additional two and one-half manehs, which we received on loan without interest from Iddin-Marduk, the son of Iqisa-ablu, the son of Nur-Sin, and we invested it all in this house. In the fourth year of Nabonidos, king of Babylon, I claimed my dowry from my husband Ben-Hadad-nathan, and he of his own free will gave me, under deed and seal, the house in Borsippa and the eight roods on which it stood, and assigned it to me for ever, stating in the deed he gave me that the two and one-half manehs which Ben-Hadad-nathan and Bunanitum had received from IddinMarduk and laid out in buying this house had been their joint property.

Suit Involving a Babylonian Widow Trying to Recover Her Property

Morris Jastrow said: “An example taken from the neo-Babylonian period will illustrate the spirit by which the judges were actuated in deciding the complicated cases that were frequently brought before them. It is the case of a widow Bunanit, who brings suit to recover property, devised to her by her husband, which has been claimed by her brother-in-law.[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Her case is stated in detail: “Bunanit, the daughter of Kharisa, declared before the judges of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, as follows: “Apil-addunadin, son of Nikbadu,” took me to wife, receiving three and a half manas of silver as my dowry, and one daughter I bore him. I and Apil-addunadin, my husband, carried on business with the money of my dowry, and bought eight GI of an estate in the Akhula-galla quarter of Borsippa, for nine and two thirds manas of silver, besides two and a half manas of silver which was a loan from Iddin-Marduk, son of Ikischa-aplu, son of Nur-Sin, which we added to the price of said estate and bought it in common.

““In the fourth year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, I put in a claim for my dowry against my husband Apil-addunadin, and of his own accord he sealed over to me the eight GI of said estate in Borsippa and transferred it to me for all time, and declared on my tablet as follows:‘21/2manas of silver which Apil-addunadin and Bunanit borrowed from Iddin-Marduk and turned over to the price of said estate they held in common, That tablet he sealed and wrote the curse of the gods on it.’

““In the fifth year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, I and my husband Apil-addunadin adopted Apil-adduamara as son, and made out the deed of adoption, stipulating two manas and ten shekels of silver and a house-outfit as the dowry of Nubta, my daughter. My husband died, and now A?abi-ilu, son of my father-in-law, has put in a claim for said estate and all that has been sealed and transferred to me, including Nebo-nur-ili whom we obtained from Nebo-akh-iddin. Before you I bring the matter. Render a decision.”

Reaching a Legal Decision in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: ““The case has been stated with great clearness. The legal point involved, because of which the brother-in-law puts in a claim on behalf of the deceased husband’s family, turns on the question whether the wife is entitled to the entire estate, seeing that her original dowry was only three and one half manas, or, in other words, whether the husband had a right to turn over to her the whole property on the ground that it was her dowry which, through business transactions conducted in common, had increased to nine and two thirds manas. Bunanit, in stating her case, lays great stress, it will be observed, on the circumstance that she and her husband did all things in common —bartered in common, bought in common, borrowed in common, adopted a son in common, and acquired a slave in common. The decision rendered by the judges is remarkably just, manifesting a due regard for the ethics of the situation, and based on an examination of the various documents or tablets in the case and which in such an instance had to be produced. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The document continues as follows: “The judges heard their complaints, and read the tablets and contracts which Bunanit had laid before them. To A?abi-ilu they grant nothing of the estate in Borsippa, which in lieu of her dowry had been transferred to Bunanit, nor Nebo-nftr-ili, whom she and her husband had bought, nor any of the property of Apil-addunadin. They confirmed the documents of Bunanit and Apil-adduamara. The sum of two and one half manas of silver is to be returned forthwith to Iddin-Marduk who had advanced it for the sale of the house. Then Bunanit is to receive three and one half manas of silver—her dowry—and a share of the estate. Nebo-nur-ili is given to Nubta in accordance with the agreement of her father. The names of the six judges through whom the said decision was rendered are then given, followed by the names of two scribes and the date Babylon, 26th of Ulul (6th month), 9th year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon.”

“The balance of the estate evidently passed over to the adopted son. Bunanit won her case against her brother-in-law, but it looks on the surface as though she had not won all that she had claimed. The judges practically ignored the transfer of the entire estate to her, for they granted her merely her dowry and the share of her husband’s property to which as widow she was entitled. Had there not been an adopted son, the claim of A?abi-ilu would probably have been upheld for the balance of the estate, exclusive of the slave. Bunanit is obliged to confess that her husband transferred the property “of his own accord,” which means that it was not upon an order of the court, and therefore not legally-established. It is safe to assume that the court would not have regarded such a transaction as legal, for despite the fact that the pair do not adopt a son until after the transfer, the judges allowed the widow her dowry only and her share of the estate. On the other hand, though it might appear that, as a partner, Bunanit would only have been responsible for one half of the amount borrowed from Iddin-Marduk, the judges, by ignoring the transfer, could order that Iddin-Marduk must be paid in full out of the property left by Apil-addunadin.”

Punishments in Mesopotamia: an Eye for an Eye, Fines and Exile

flogging rebels in Assyria

Hammurabi justice could be quite cruel. One law stated: “If a fire has broken out in a man’s house and a man who has gone to extinguish it has coveted an article of the owner of the house and takes the article of the house, that man shall be cast in that fire.” Hammurabi instituted the death penalty for illegal timber harvesting after wood became in such short supply that people took their doors with them when they moved. The shortages degraded agriculture land and cut production of chariots and naval ships.

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“In the criminal law the ruling principle was the lex talionis. Eye for eye, tooth for tooth, limb for limb was the penalty for assault upon an amelu. A sort of symbolic retaliation was the punishment of the offending member, seen in the cutting off the hand that struck a father or stole a trust; in cutting off the breast of a wet-nurse who substituted a changeling for the child entrusted to her; in the loss of the tongue that denied father or mother (in the Elamite contracts the same penalty was inflicted for perjury); in the loss of the eye that pried into forbidden secrets. The loss of the surgeon's hand that caused loss of life or limb or the brander's hand that obliterated a slave's identification mark, are very similar. The slave, who struck a freeman or denied his master, lost an ear, the organ of hearing and symbol of obedience. To bring another into danger of death by false accusation was punished by death. To cause loss of liberty or property by false witness was punished by the penalty the perjurer sought to bring upon another. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

Not long after shekels appeared as a means of exchange, kings began levying fines in shekels as a punishment. Around 2000 B.C., in the city of Eshnunna, a man who bit another man's nose was fined 60 shekels. A man who slapped another man in the face had to pay up 20 shekels.

Hermann and Johns wrote: “The commonest of all penalties was a fine. This is awarded by the Code for corporal injuries to a muskinu or slave (paid to his master); for damages done to property, for breach of contract. The restoration of goods appropriated, illegally bought or damaged by neglect, was usually accompanied by a fine, giving it the form of multiple restoration. This might be double, treble, fourfold, fivefold, sixfold, tenfold, twelvefold, even thirtyfold, according to the enormity of the offence.

“Exile was inflicted for incest with a daughter; disinheritance for incest with a stepmother or for repeated unfilial conduct. Sixty strokes of an ox-hide scourge were awarded for a brutal assault on a superior, both being amelu. Branding (perhaps the equivalent of degradation to slavery) was the penalty for slander of a married woman or vestal. Deprivation of office in perpetuity fell upon the corrupt judge. Enslavement befell the extravagant wife and unfilial children. Imprisonment was common, but is not recognized by the Code.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024