Home | Category: Art and Architecture

Shedu from Assyria

ASSYRIAN AND BABYLONIAN SCULPTURE

The Assyrian sculptures show to what perfection the art of the joiner had attained at the time when Nineveh was the mistress of the civilized world. The art of the stone-cutter had attained an even higher perfection at a very remote date. Indeed, the seal-cylinders of the time of Sargon of Akkad display a degree of excellence and finish which was never surpassed at any subsequent time. The same may be said of the basrelief of Naram-Sin discovered at Diarbekr. The combination of realism and artistic finish displayed in it was never equalled even by the bas-reliefs of Assyria, admirable as they are from many points of view. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The early stone-cutters of Chaldea tried their skill upon the hardest materials, and engraved upon them the minutest and most delicate designs. Hæmatite was a favorite material for the seal-cylinder; the statues of Tello are carved out of diorite, which was brought from the Sinaitic Peninsula, and stones of similar hardness were manufactured into vases. That such work should have been attempted in an age when iron and steel were as yet unknown seems to us astonishing. Even bronze was scarce, and the majority of the tools employed by the workmen were made of copper, which was artificially hardened when in use.

Emery powder or sand was also used, and the lathe had long been known. When iron was first introduced into the workshops of Babylonia is doubtful. That the metal had been recognized at a very early period is clear from the fact that in the primitive picture-writing of the country, out of which the cuneiform syllabary developed, it was denoted by two characters, representing respectively “heaven” and “metal.” It would seem, therefore, that the first iron with which the inhabitants of the Babylonian plain were acquainted was of meteoric origin.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Palace Sculptures” by Paul Collins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Sculpture” by Julian E. Reade (1998) Amazon.com;

“Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum” by John E. Curtis, Julian E. Reade Amazon.com;

“The Mythology of Kingship in Neo-Assyrian Art” by Mehmet-Ali Ataç (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Bahrani Zainab (2017) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Art, Objects from Ur and Al-'Ubaid” by The British Museum and Terence C. Mitchell (1969) Amazon.com;

“Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur” by Richard L. Zettler and Lee Horne (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art) by Henri Frankfort , Michael Roaf, et al. (1996) Amazon.com;

“Art of the Ancient Near East: A Resource for Educators” by Kim Benzel, Sarah Graff, Yelena Rakic Amazon.com;

“Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus”

by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels (2003) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs” by Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, McGuire Gibson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Meaning of Color in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Shiyanthi Thavapalan (2019) Amazon.com;

“Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C.”

by Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

Imdugud grapsing a pair of deer from Tell al-Ubaid

Early Mesopotamian Sculpture 2900–2350 B.C.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the so-called Early Dynastic period (ca. 2900–2350 B.C.), life in the cities of Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq) was focused on the gods, who were believed to dwell in specially constructed temples. However, judging from the few excavated examples, these buildings appear not to have been congregational in nature. Access to the small central shrines was probably limited, most likely to the priests who served the god's needs. It was perhaps due to this lack of access that the elite commissioned images of themselves to be carried into the god's presence. These statues embodied the very essence of the worshipper so that the spirit would be present when the physical body was not. Quite how, or indeed if, the statues were presented to the god is unknown, as none have been discovered in situ but rather found buried in groups under the temple floor, or built into cultic installations such as altars, or scattered in pieces in the shrine and surrounding rooms, perhaps having been damaged when the temple was plundered or rebuilt in antiquity. Hundreds of such statues or fragments have been excavated and at no other time in the history of the ancient Near East has nonroyal sculpture survived in such abundance. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The "Early Dynastic Sculpture, 2900–2350 B.C.", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The votive statues are of various sizes and usually carved in gypsum or limestone. They depict men wearing fringed or tufted fleece skirts, and women wearing fringed or tufted dresses draped over one shoulder. Many have inlaid eyes and painted hair. The statues are usually carved with the hands clasped, right over left, at the chest or waist in a gesture of attentiveness. Some figures hold cups or branches of vegetation. Standing figures often step forward with the left foot. Male heads are frequently shown bald but sometimes wear beards, while female figures can have a variety of hairstyles or headdresses. Facial characteristics offer little variation from one statue to the next. \^/

“A large number of statues were discovered in temples at the sites of Tell Asmar, Khafaje, and Tell Agrab close to the Diyala River, a major tributary of the Tigris in eastern Mesopotamia. There is a wide stylistic range in the hundreds of dedicatory statues found here. Both naturalistic and highly abstract styles exist, possibly contemporaneous in date, originating perhaps from different workshops. A long beard and side locks characterize some male figures. \^/

“One of the largest collections of sculpture was discovered at the site of Nippur in a temple dedicated to Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of abundance. The Metropolitan Museum was a sponsor of the excavations during the 1957–58 and 1960–61 seasons and was accorded a share of the finds. Along with the statues were stone bowls, plaques, and inlays that were found either as hoards or scattered throughout the building. The most spectacular finds were made in Level VII dating to the later Early Dynastic period. Some figures from Nippur have a cuneiform inscription on their back or shoulder giving the name of the god and the profession and name of the donor. \^/

“Dedicatory sculptures have been found at a number of sites throughout Mesopotamia and neighboring regions, including Susa in southwest Iran, Tell Chuera in Syria, and Ashur in northern Mesopotamia. Almost half of the approximately seventy surviving examples of inscribed sculpture come from the site of Mari in Syria, where sculpture in a distinct style was found strewn among the destruction debris of the temples of Ishtar, Ishtarat, and Ninni-zaza. The sculpture from Mari is defined by its vitality and relative naturalism, with careful modeling and accurate proportions. The male figures from Mari often wear beards elaborated by patterns such as drilled holes-a hallmark of Mari sculpture-that separate the wavy strands of the beard. Among the many statues discovered at the site are figures of seated males and females and a masterpiece of carving that represents a musician sitting cross-legged on a woven cushion and named Ur-Nanshe in the inscription on his shoulder.” \^/

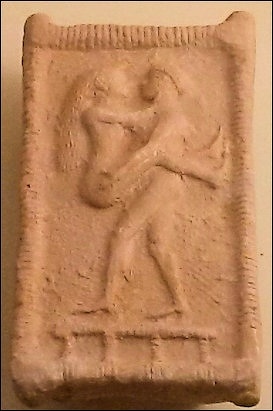

Votive Tablets from Mesopotamia

Two similar votive tablets of the ruler Ur-Nina and his family have been found at Telloh. One of these is also in the Louvre; the other in a museum in Istanbul.Morris Jastrow said: “Ur-Ninâ—naked to the waist—is represented in the upper row with a workman’s basket on his head, symbolising his participation in the erection of a sacred edifice. In the accompanying inscription he records his work at the temples of Ningirsu and of Nina and other constructions within the temple area of Lagash. Behind him stands a high official—presumably a priest—with a libation cup in his hand, and before the king are five of his children. The lower row represents the king after the completion of the work pouring a libation. Behind him again the attendant, and before him four other children. The figure with the basket on the head became a common form of a votive offering (see Pl. 29) and persisted to the end of the Assyrian empire as is shown by the steles of King Ashurbanapal and his brother, Shamash-shumukin with such baskets. (See Lehmann, Shamash-shumukin, Leipzig, 1892.)[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“A votive offering to the god Ningishzida” — made of green steatite, found at Telloh and now in the Louvre — features an “elaborately sculptured design consisting of two serpents entwined around a staff, backed by two fantastic figures, winged monsters with serpents’ heads and tails ending in a scorpion’s sting.” Copper votive Statuettes from Telloh now in the Louvre “represent female figures with hands folded across the breast, and terminating in a point which would indicate that they were to be stuck into the ground, or possibly into the walls.

“Votive Tablet of Ur-Enlil, Patesi of Nippur” (c 3000 B.C.) is a imestone tablet with brief votive inscription found by Haynes at Nippur and now in Istanbul. “The upper scene represents a naked worshipper who is none other than Ur-Enlil himself, offering a libation to Enlil, the chief god of Nippur. In accordance with the principle of symmetry, so frequently illustrated on the seal cylinders, the scene is given in double form. The lower section shows a goat and sheep followed by two men, one with a vessel on his head the other with a stick in his hand. The animals may represent sacrifices to be offered to the god. Another limestone tablet has been found at Nippur, likewise showing a naked worshipper—perhaps the same Ur-Enlil—before Enlil and a gazelle in the lower section. The naked worshipper—a custom of primitive days for which there are parallels in other religions—is also found on a limestone bas-relief from Telloh.

Copper votive offerings from Lagash, found at Telloh and now in the Louvre, include “two kneeling figures represent deities—probably in both cases Ningirsu—and bearing dedicatory inscriptions of Gudea, the Patesi of Lagash (c. 2350 B.C.) The two bulls contain dedicatory inscriptions of Gudea to the goddess Inninna for her temple E-Anna in Girsu (a section of Lagash). The two female figures with baskets on their heads, likewise bear dedicatory inscriptions. Similar figures—male and female—have been found with inscriptions of various rulers. The basket on the head is the symbol of participation in the erection of a sacred edifice, as in the case of Ur Ninâ.

In “Babylonian Type of Gilgamesh,” a terra-cotta inage found at Telloh and in the Louvre, “the hero who is naked holds a vase from which a jet of water streams to either side, symbolising the association of the solar hero with the sun-god, who is frequently represented with streams.

Stele and Bas-Reliefs from Mesopotamia

On a Stele of Naram-Sin, King of Agade (c. 2470 B.C.). Morris Jastrow said: “It represents the king conquering enemies in a mountainous district. The peak of the mountain is pictured as rising to the stars. Some of the king’s foes are fleeing, others are pleading for mercy. Found at Susa, whither it was presumably carried as a trophy by the Elamites in one of their incursions into Babylonia, perhaps by Shutruk-Nakhunte,' king of Elam, c. 1160 B.C. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Bas-Relief of Naram-Sin (basalt) found in 1891 near Diarbekr, Turkey and now in a museum in Istanbul “records the victories of the king which he attributes to the aid of Ea, and pronounces curses on anyone who destroys or removes this monument of himself.” Examples of Semitic types include: “Two portraits of Hammurabi, king of Babylonia (c. 1958-1916 B.C.), a Bas-relief on a clay tablet, recording the homage of a high official Itur-Ashdum to Hammurabi and to the goddess Ashratum—a designation of the consort of the “Amorite” deity Adad. Now in the British Museum.

The Stele of E-annatum, Patesi (and King) of Lagash (c . 2900 B.C.) Is a remarkable limestone monument carved on both sides with designs and inscriptions. It was found at Telloh in badly mutilated condition but careful study of its recovered pieces reveals that it represents the conquest of the people of Umma by Eannatum, and records the solemn agreement made between Eannatum and the people of Umma. The upper piece represents vultures flying off with the heads of the slain opponents—to illustrate their dreadful fate. These dead are shown in the second figure, while in the third others who have fallen in battle are carefully arranged in groups and a burial mound is being built over them by attendants who carry the earth for the burial in baskets placed on their heads. Traces of a ceremonial offering to the dead are to be seen in another fragment. The designs on the obverse are symbolical—the chief figure being the patron deity, Ningirsu with the eagle on two lions as the emblem of the god (see Pl. 5, Fig. 1) in his hand, and the net in which the deity has caught the enemies.

Assyrian Stele

Apkallu from Nimrud

“Esarhaddon, King of Assyria (680-669 B.C.) with two Royal Prisoners” is an example of an Assyrian Type image: “Before the king are two royal prisoners, Tirhaka, the King of Ethiopia, and Ba’alu the King of Tyre. To emphasise his greatness in contrast to the insignificance of his enemies, the king portrays himself as of commanding stature. At the head of the stone, the emblems of the great gods of Assyria, Ashur, Sin, Shamash, Ishtar, Marduk, Nebo, Ea, Ninib, and Sibitti (seven circles), with Ashur, Ishtar of Nineveh, Enlil, and Adad standing on animals. Diorite stele found at Sendschirli in Northwestern Syria. Now in the Royal Museum of Berlin.

:King Ashurbanapal in Lion Hunt and pouring Libations over Four Lions killed in the Hunt” on an alabaster slab “is one of a large series illustrative of the royal sport in Assyria—hunting lions, wild horses, gazelles, and other animals...Ashurbanapal with his attendants behind him is pouring a libation over four lions killed in the hunt. An altar is in the centre, and a pole or tree such as is often seen on the seal cylinders when sacrificial scenes are portrayed. The musicians to the left precede the attendants carrying a dead lion on their backs...These slabs formed the decoration of portions of the walls in the large halls of the palace of Ashurbanapal at Kouyunjik (Nineveh). They were found by Layard and are now one of the great attractions of the British Museum. As specimens of the art of Assyria they are of deep interest, but no less as illustrations of life and manners, supplemented by the equally extensive series of slabs which illustrate the campaigns waged by this king. Similar martial designs in the palace of Sargon at Khorsabad illustrating his campaigns.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024