Home | Category: Art and Architecture

CLAY CRAFTSMANSHIP IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

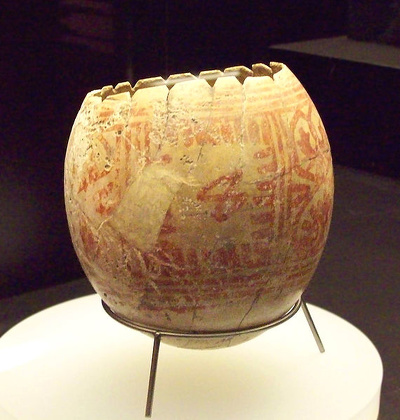

Ishtar vase Morris Jastrow said: “The architecture of both temple and palace is massive and, in consequence of the lack of a hard building-material in the Euphrates Valley, it is perhaps natural that the brick constructions developed in the direction of hugeness rather than of beauty. The drawings on limestone votive tablets and on other material during this early period are generally crude. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“More skill is displayed in incisures on seal cylinders of various kinds of material, bone, shell, quartz, chalcedony, lapis-lazuli, hematite, marble, and agate. Though serving the purely secular purpose of identifying an individual’s personal signature to a business document—written on clay as the usual writing-material—these cylinders incidentally illustrate the bond between culture and religion by their engraved designs, which are invariably of a religious character, —such as the adoration of deities, sacrificial scenes, or representations of myths or mythical personages. Though marred frequently by grotesqueness, the metal work—in copper, bronze, or silver—is on the whole of a relatively high order, particularly in the portrayal of animals. The human face remains, however, without expression, even where, as in the case of statues chiselled out of the hard diorite, imported from Arabia, the features are carefully worked out.

“This close relationship between religion and culture, in its various aspects—political, social, economic, and artistic,—is thus the distinguishing mark of the early history of the Euphrates Valley that leaves its impress upon subsequent ages. Intellectual life centres around religious beliefs, both those of popular origin and those developed in schools attached to the temples, in which, as we shall see, speculations of a more theoretical character were unfolded in amplification of popular beliefs.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Bahrani Zainab (2017) Amazon.com;

“Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur” by Richard L. Zettler and Lee Horne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Art, Objects from Ur and Al-'Ubaid” by The British Museum and Terence C. Mitchell (1969) Amazon.com;

“An Examination of Late Assyrian Metalwork: with Special Reference to Nimrud”

by John Curtis (2013) Amazon.com

“First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East” by Dominique Collon, British Museum Publications, 1987 Amazon.com;

“The Published Ivories from Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud” by Georgina Herrmann , H. Coffey, et al. (2004) Amazon.com;

“Painting Pots – Painting People: Late Neolithic Ceramics in Ancient Mesopotamia”

by Walter Cruell, Inna Mateiciucova, et al. | Feb 28, 2017 Amazon.com;

“II Workshop on Late Neolithic Ceramics in Ancient Mesopotamia: Pottery in Context”

by Anna Gómez Bach, Jörg Becker, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pottery from Tell Khaiber: A Craft Tradition of the First Sealand Dynasty: 1" (Archaeology of Ancient Iraq) by Daniel Calderbank (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art) by Henri Frankfort , Michael Roaf, et al. (1996) Amazon.com;

“Art of the Ancient Near East: A Resource for Educators” by Kim Benzel, Sarah Graff, Yelena Rakic Amazon.com;

“Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus”

by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels (2003) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs” by Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, McGuire Gibson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Meaning of Color in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Shiyanthi Thavapalan (2019) Amazon.com;

“Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C.”

by Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

Ostrich Egg Cups and Ivory in Ancient Mesopotamia

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: For wealthy Bronze or Iron Age southern Europeans, nothing beat an ostrich eggshell cup. It is known that these coveted luxury items were imported from the Levant and Egypt, but until recently, little has been understood about the ancient ostrich egg trade. A team lead by University of Bristol archaeologist Tamar Hodos has compared ancient ostrich eggshell artifacts to modern ostrich eggs to learn how these precious objects were acquired. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2020]

A ninth-century B.C. inscription at the Neo-Assyrian capital of Nimrud in modern Iraq suggests that royals may have held ostriches captive for hunting, but Hodos and her team ruled out the idea that the big birds were kept to harvest their eggs. Instead, they found that ancient eggshells resembled modern wild ostrich eggs more than they did those from farmed ostriches. “That means somebody had to track the ostriches to their nests to steal their eggs,” says Hodos. “It would have been dangerous. They can kill you with one kick.” The team also studied the chemical composition of the eggshells and found they could distinguish between eggs from cool, dry climates and those from warmer, wetter ones. Curiously, ancient ostrich eggshells from one climate zone have been excavated at sites in the other zone, suggesting the ostrich egg business was unexpectedly complex.

Carving in ivory was another trade followed in Babylonia and Assyria. The carved ivories found on the site of Nineveh are of great beauty, and from a very early epoch ivory was used for the handles of sceptres, or for the inlaid work of wooden furniture. The “ivory couches” of Babylonia made their way to the West along with the other products of Babylonian culture, and Amos (vi. 4) denounces the wealthy nobles of Israel who “lie upon beds of ivory.” Thothmes III. of Egypt, in the sixteenth century B.C., hunted the elephant on the banks of the Euphrates, not far from Carchemish, and, as late as about 1100 B.C., Tiglath-pileser I. of Assyria speaks of doing the same. In the older period of Babylonian history, therefore, the elephant would have lived on the northern frontier of Babylonian domination, and its tusks would have been carried down the Euphrates along with other articles of northern trade. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Crafts, Coffins and Liver Model from Mesopotamia

A silver vase found at Telloh, and now in the Louvre, is considered to be the finest specimen of early metal work of Babylonia. Morris Jastrow said: “The central design of a votive offering to his god Ningirsu, deposited in the temple E-Ninnu. “consists of four lion-headed eagles, of which two seize a lion with each talon, and a third eagle seizes a couple of deer and the fourth a couple of ibexes. The eagle appears to have been the symbol of Ningirsu, while the lion,—commonly associated with Ishtar—may represent Bau, the consort of Ningirsu—the Ishtar of Lagash. The combination would thus stand for the divine pair. Dr. Ward (Seal Cylinders of Western Asia, p. 34 seq.) plausibly identifies this design with the bird Im-Gig, designated in the inscriptions of Gudea as the emblem of the ruler. The same design of the lion-headed eagle seizing two lions is found on other monuments of Lagash.” [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Early types of Babylonian coffins were bath-tube shaped. Later ones were slipper-shaped coffins. Those from the Persian period frequently have glazed covers with ornamental designs. The coffins may be regarded as typical of the mode of burying the dead in coffins in Babylonia and Assyria, though various other modes existed as well. Excavations in Nippur, Assyria and Babylonia have uncovered graves vaulted in by brick walls. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Images of Mesopotamian Divination include: 1) Drawing of Sheep’s Liver with Latin and Babylonian Terms for Chief Part; 2) Omen School—Tablet from Ashurbanapal’s Library, showing Finger-shaped Appendix to Upper Lobe of Liver. Jastrow said: A Clay Model of Sheep’s Liver now in the British Museum is a model of a sheep’s liver, used as an object of instruction in hepatoscopy in some temple school. The chief parts of the liver are shown. The object is covered with inscriptions which give the prognostications derived from signs on the liver, each prognostication referring to some sign near the part of the liver where the words stand. The characters point to the time of Hammurabi (c. 2000 b.c) as the date of the model.”

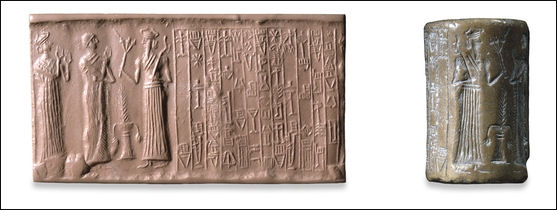

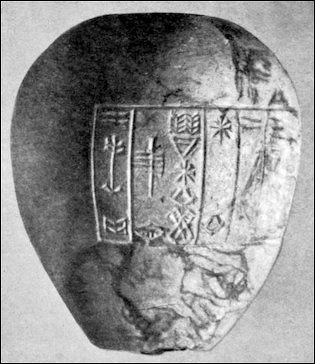

Mesopotamian Seals

Mesopotamian seals are exquisitely carved and engraved cylinders of stone or metal that look like miniature rotating drums. When rolled over soft clay they leave a reverse image or a message, often in extraordinary detail. They were often used as signature much like chops used by Chinese and Japanese today and waxed seals used in medieval Europe. If ink is applied to the seals and they are rolled on a piece of paper they will print the objects or symbols on the seal.

Mesopotamia cylinder seals are made of marble, lapis lazuli, serpentine, alabaster. When a cylinder is rolled across soft clay, it leaves a raised repeating impression, making a clay frieze used to seal containers and storerooms in Mesopotamia 6,000 years ago. In cities such as Ur goods were sealed for purely practical reasons with clay images of heros with curls and Shamash the sun god.

There were large seals and seal rings. Most seals were about an inch high and came in widths defined by the images on them. They were used to mark documents of property and were worn as bracelets or necklaces and were often buried with their owners when they died.

Cylinder seal of cattle

Seals unearthed at Mesopotamian sites have relief carvings and elaborate inlay portraits of ordinary people, kings, goats, lions, soldiers, farmers, heroes, gods and goddesses doing various things. Describing the seals at a modest exhibition of cylinder at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York in 1998, Verlyn Klinkenborg wrote in the New York Times, “The seals depict an utterly unfamiliar world where a nude bearded hero with six curls coexists with a bull-man, water gods and a lion-griffin. What is striking is not just the strangeness of this distant world but the clarity with which it is represented. In cylinders no taller than an inch or two, Mesopotamian artists carved images that, when fleshed out in clay, have a fullness, a torsional dimension, that allows the musculature of their hips to flex toward the viewer. A lion sinks its teeth into a bull, and doing so it reaches behind the bull's head and shows its face to the viewer, the lion's power expressed in the extremity of that arc.” [Source: Verlyn Klinkenborg, New York Times, March 01, 1998] Some Sumerian seals are more than 5000 years old. One lion hunt seal tells the story of the beginning of the kingship and the beginning of the state. A man is pictured in a turban and long skirt fighting lions with a spear and bow and arrow. The theme of a king fighting lions was passed on to other Mesopotamian kingdoms.

Examples of Seal Cylinders from Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “These two plates of seal cylinders—all found at Telloh—may be taken as typical of the illustrations found on these objects, which served the purpose of personal seals, used by the owners as their signatures to business documents. They were rolled over the clay tablets on which business transactions were inscribed. Presumably the cylinders were also used as amulets. (See Herodotus, Book I, § 195, who says that every Babylonian “carries a seal.”) The design in the centre of Pl. 6 represents Gilgamesh, the hero of the Babylonian Epic, attacking a bull, while another figure—presumably Enkidu (though different from the usual type)— is attacking a lion. This conflict with animals which is an episode in the Epic is very frequently portrayed on seal cylinders in a large number of variations. Another exceedingly common scene portrays a seated deity into whose presence a worshipper is being led by a priest—or before whom a worshipper directly stands—followed by a goddess, who is the consort of the deity and who acts as inter-ceder for the worshipper. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“On Pl. 6 there are three specimens of this scene; on Pl. 7 likewise three. An altar, tree, or sacrificial animal— and sometimes all three—are added to the design. The seated god is commonly Shamash, the sun-god, but Sin, the moon-god, Ea, and Marduk, Adad, Ningirsu (and probably others) are also found, as well as goddesses. The seated god with streams issuing from both sides on Pl. 7 (5th row to the right) is certainly Shamash; so also the one in the opposite comer with rays protruding from his shoulders. Instead of the seated god, we frequently find the god in a standing posture of which Pl. 7 contains three examples.

calcite cylinder seal

“The one on the lowest row to the left is Shamash, the sun-god, with one leg bare and uplifted—symbolising the sun rising over the mountain; the other in the fourth row to the right is probably the god Marduk with the crook (or scimitar) standing on a gazelle, while the third—on the third row in the centre —is interesting as being, according to the accompanying inscription, a physician’s seal. The deity represented is Iru—a form or messenger of Nergal, the god of pestilence and death, which suggests a bit of grim (or unconscious) humour in selecting this deity as the emblem of the one who ministers unto disease. The accompanying emblems have been conjectured to be the physician’s instruments, but this is uncertain. We have also two illustrations of the popular myths which were frequently portrayed on these cylinders—both on Pl. 7.

“The one in the centre on the second row is an episode in a tale of Etana—a shepherd—who is carried aloft by an eagle to the mountain in which there grows the plant of life; the second— on the fourth row in the centre—represents Nergal’s invasion of the domain of Ereshkigal, the mistress of the lower world, and his attack on the goddess—crouching beneath a tree. The other scene on the cylinder seems to be an offering to Nergal, as the conqueror and, henceforth, the controller of the nether world. The remaining designs similarly have a religious or mythical import. The seals of the Neo-Babylonian and Persian periods show a tendency to become smaller in size and to embody merely symbols instead of a full scene.”

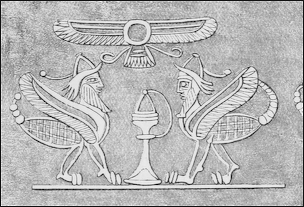

Boundary Stones with Symbols of the Gods

Boundary Stones with symbols of the gods include one from the reign gf the Kassite King Nazi-maruttash (c. 1320 B.C.) found at Susa and now in the Louvre. Morris Jastrow said: “The symbols shown on Face D are: in the uppermost row, Anu and Enlil, symbolised by shrines with tiaras; in the second row—probably Ea [shrine with goat-fish and ram’s head ], and Ninlil (shrine with symbol of the goddess); third row—spear-head of Marduk, Ninib (mace with two lion heads); Zamama (mace with vulture head); Nergal (mace with lion's head); fourth row, Papsukal (bird on pole), Adad (or Ranunan—lightning fork on back of crouching ox); running along side of stone, the serpen t-god, Siru. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

scorpion men

“On Face C are the symbols of Sin, the moon-god (crescent); Shamash the sun-god (solar disc); Ishtar (eight-pointed star); goddess Gula sitting on a shrine with the dog as her animal at her feet; Ishkhara (scorpion); Nusku, thefire-god (lamp). “The other two faces (A and B) are covered with the inscription. Nineteen gods are mentioned at the dose of the inscription, where these gods are called upon to curse any one who defaces or destroys the stone, or interferes with the provisions contained in the inscription.

Another boundary stone of which two faces are shown is dated in the reign of Marduk-baliddin, King of Babylonia (c. 1170 B.C.) and was found at Susa and now in the Louvre. The symbols shown in the illustration are: Zamama (mace with the head of a vulture); Nebo (shrine with four rows of bricks on it, and homed dragon in front of it); Ninib (mace with two lion heads); Nusku, the god of fire Gamp); Marduk (spear-head); Bau (walking bird); Papsukal (bird perched on pole); Anu and Enlil (two shrines with tiaras); Sin, the moon-god (crescent). In addition there are Ishtar (eight-pointed star), Shamash (sun disc), Ea (shrine with ram's head on it and goat-fish before it), Gula (sitting dog), goddess Ishkhara (scorpiqn), Nergal (mace with lion head), Adad (or Ramman—crouching ox with lightning fork on bade), Sim—the serpent god (coiled serpent on top of stone).

“All these gods, with the exception of the last named, are mentioned in the curses at the close of the inscription together with their consorts. In a number of cases, (e. g., Shamash, Nergal, and Ishtar) minor deities of the same character are added which came to be regarded as forms of these deities or as their attendants; and lastly some additional gods notably Tammuz (under the form Damu), his sister Geshtin-Anna (or belit seri), and the two Kassite deities Shukamuna and Shumalia. In all forty-seven gods and goddesses are enumerated which may, however, as indicated, be reduced to a comparatively small number.”

Mesopotamian Pottery and Glass

Pottery vessels were introduced to the Near east around 6000 B.C. They were used primarily for storing liquids, grains and other items. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia around 4000 B.C.

Akkadian macehead of Sargo

Alabaster and lapis lazuli were fashioned into sculptures, bowls and jewelry. Some of the finest pieces of art from Mesopotamia includes finely-rendered alabaster vases from Syria with a short neck, pointed base, sweeping sides and a shimmering white color than gleams in the sun.

An ancient cuneiform time was inscribed with the following recipe: "Take 60 parts sand, 180 parts ash from sea plants, 5 parts chalk, and heat them all together. A professor at Alfred University followed these directions over 1600̊F driftwood fire. After two hours nothing exceptional was produced. The fire was made a little hotter. The result: glass.

The earliest man-made glass objects, mainly non-transparent glass beads, are thought to date back to around 3500 BC, with finds in Egypt and Eastern Mesopotamia. In the third millennium, in central Mesopotamia, the basic raw materials of glass were being used principally to produce glazes on pots and vases. The discovery may have been coincidental, with calciferous sand finding its way into an overheated kiln and combining with soda to form a colored glaze on the ceramics.

Before glassblowing was developed in the 1st century B.C. “core glass” vessels were made by forming the glass around a solid metal rod that was taken out as the glass cooled (the hollow glassmethod). The oldest fragments of glass vases (evidence of the origins of the hollow glass industry) date back to the 16th century B.C., and were found in Mesopotamia. Hollow glass production was also evolving around this time in Egypt. [Source: Glass Online]

Bronze Art from the Mesopotamia and Greco-Roman Periods

In 1990 the Merrin Gallery in New York Street hosted an exhibition simply called ''Bronze!''The 44 objects included portrait heads, mythological figures, lamps, ax heads, vessels, amulets and furniture fragments were made between 2300 B.C. and A.D. 300 in lands bordering the Mediterranean. Among the 16 items for sale were a six-inch bronze bust of Serapis, the Mesopotamian god of corn, for $38,000, and a near life-sized bust of a serene-faced female Roman deity that may have served as a ship's figurehead. Both date to the first century A.D for to $1.25 million. ''Bronze is a cold metal, but the best pieces capture a warm, energetic human feeling,'' Edward H. Merrin, the gallery's founder, told the New York Times. ''When it works, bronze is magical.'' [Source: Rita Reif, New York Times, October 14, 1990]

Rita Reif wrote in the New York Times, “Included are Sumerian, Phoenician, Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Hellenistic, Iranian, Etruscan and Roman objects. The broad range of expressiveness includes the raw power of a Sardinian Nuragic priest from the ninth or eighth century B.C., his outsized hand raised in benediction; the quiet elegance of a high-stepping sixth- or fifth-century B.C. Etruscan horse and the seductiveness of a wildly dancing Hellenistic maenad from about the first century B.C.

Several of the most compelling objects are artifacts of the Bronze Age (3500 to 1000 B.C.), which combine a stark simplicity of form, technological sophistication and complex meanings. Two are not bronze at all, but arsenic copper - a material used before bronze which is often mistaken for it. One is a bug-eyed Sumerian deity from about 2300 B.C., with bull's ears and horns, wearing a tall hat, which is actually the finial of a scepter. The other is a Hittite ax-head from about 1800 B.C., engraved on each side with an image of an earth goddess holding her breasts.

Bronzes proliferated when the cultures represented in the show were at their peak, even though some of the images may impress viewers as lacking in refinement. Mr. Merrin compared two quite different objects in the show - an aristocratic warrior from about 1700 B.C. and an Iranian idol from around the 9th century B.C. ''The striding Phoenician warrior has a presence,'' Mr. Merrin said. ''He is obviously a personage of some importance - tall, elegant, with large feet and wearing a beehive-shaped crown, a man to be reckoned with. The figure is only 10 inches tall but has a majesty that, when placed against a 10-foot wall, fills it.''

The mythical Iranian idol, crafted as if by a child, is a ninth- or eighth-century female, haunting and hollow-eyed, with a large nose in an outsized diamond-shaped head, her shrunken arms raised joyously high in the air. ''I smile every time I see her,'' Mr. Merrin said. ''Whoever looks can get what they want from that idol. ''Bronze is so different from other materials,'' he continued. ''The artist who worked in bronze had to be somewhat better than someone who worked in terra cotta or marble. In bronze, he began working in a medium - clay, for example - that was several steps removed from the finished product. So he had to compensate for that. The artist had to understand the limitations of bronze, as well as how fast and far the molten bronze would flow before congealing, and the amount of shrinkage that would occur.''

Many of these objects served as oil lamps, vessels, handles and tools. A Babylonian spool holder made after 1800 B.C. is decorated with a pair of goddesses; a ring used for harnessing a team of chariot horses from the city of Ur in ancient Mesopotamia, in the third millennium, is embellished with a small team of asses, their foreheads inlaid with ivory. The most arresting of these useful objects is a fifth-century Corinthian helmet, a study of sweeping curves in its soaring domed top, deeply ridged forehead and large almond-shaped cutouts for the eyes. Never painted, its hammered surface glows brown, red and green.

To bronze enthusiasts, fine detailing and highly polished surfaces are always overshadowed by an exceptional patina. Brown patinas are common, but a more flamboyant palette can be found on ancient objects, especially those that were deposited in mineral-rich burial sites. An Egyptian baboon-figure of the god Thoth made between 664-525 B.C., crowned with a crescent and a full moon and inlaid with gold and silver, shed its original gold-leaf skin in the past and turned an eerie blue. But an Egyptian amulet in the form of a Horus falcon god, trampling a serpent, is deep red and green.

Crusty turquoise patinas enhance several pieces in the show, including a mirror embellished with wrestlers from the fifth century B.C. A frying-pan-shaped libation dish from the seventh century B.C. is one of the wonders of the show - its handle is in the form of a woman stretched out as if swimming while holding the vessel in her arms like a beach ball. One of the palest patinas is a rich gray - a phenomenon attributed to the object's high tin content - that covers the Iranian female idol beloved by Mr. Merrin.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024