Home | Category: Languages and Writing / Literature / Education, Transportation and Health

READING CUNEIFORM

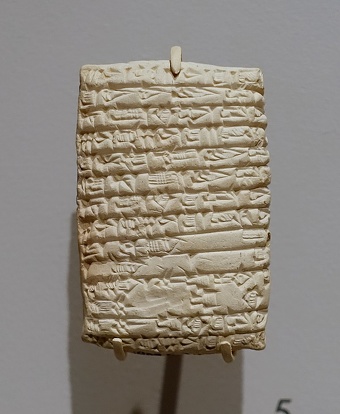

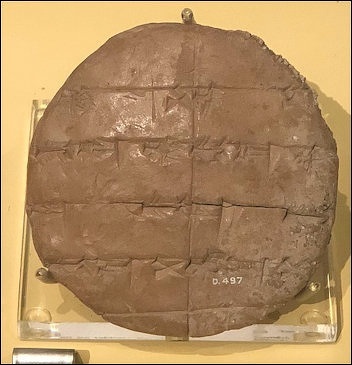

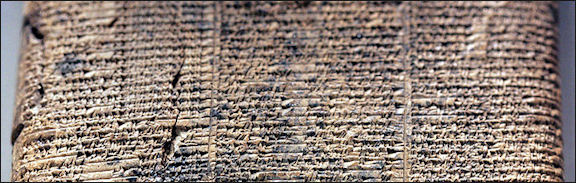

Cuneiform, the script language of ancient Sumer and Mesopotamia, consists of small, repetitive impressed characters that look more like wedge-shape footprints than what we recognize as writing. Cuneiform (Latin for "wedge shaped") appears on baked clay or mud tablets that range in color from bone white to chocolate to charcoal. Inscriptions were also made on pots and bricks. Each cuneiform sign consists of one or more wedge-shaped impressions that are made with three basic marks: a triangle, a line or curbed lines made with dashes.

Cuneiform (pronounced “cune-AY-uh-form”) was devised by the Sumerians more than 5,200 years ago and remained in use until about A.D. 80 A.D. when it was replaced by the Aramaic alphabet Jennifer A. Kingson wrote in the New York Times: "Evolving roughly at the same time as early Egyptian writing, it served as the written form of ancient tongues like Akkadian and Sumerian. Because cuneiform was written in clay (rather than on paper on papyrus) and important texts were baked for posterity, a large number of readable tablets have survived to modern times. Many of them written by professional scribes who used a reed stylus to etch pictograms into clay. [Source: Jennifer A. Kingson, New York Times November 14, 2016]

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Ancient Mesopotamian literature commonly refers to the vast — and as yet far from complete — body of writings in cuneiform script which has come down from Ancient Mesopotamia. It is mostly found on clay tablets on which the writing was impressed when the clay was still moist. The writing reads, as does the writing on a printed English page, from left to right on the line, the lines running from the top of the page downwards. There are indications, however, that cuneiform writing once read from top to bottom and then, column for column, from right to left. The tablets when inscribed were usually allowed to dry naturally, occasionally, if durability was of the essence, they were baked at a high temperature to hard ceramic.[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Enrique Jiménez wrote: Cuneiform writing knows no orthography. There is no single, standard way of writing a word. Scribes, when copying traditional texts, would adapt them to their specific dialects or spelling preferences. Consequently, the task of fragment identification becomes challenging, as the signs present in one fragment may differ from those found in another. As is the case in many ancient and modern writing systems, the same cuneiform character can represent multiple phonetic readings and whole words. When there is sufficient context, then multiple meaning is not a problem: usually there is only one correct reading for each sign. [Source: Enrique Jiménez, Chair of Ancient Near Eastern Literatures, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, The Conservation, May 25, 2023]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mesopotamian Riddle: An Archaeologist, a Soldier, a Clergyman, and the Race to Decipher the World's Oldest Writing” by Joshua Hammer (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture” by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History” by Marc Van De Mieroop (1999) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform” by Irving Finkel (2015) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform” by C. B. F. Walker (1987) Amazon.com;

“A New Workbook of Cuneiform Signs” by Daniel C Snell (2022) Amazon.com;

“Supplement to a New Workbook of Cuneiform Signs: Teaching Old Akkadian and Old Babylonian Sign Forms” by Daniel C Snell (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Archæology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions” by Archibald Henry Sayce (1906) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts from Various Collections” by Albrecht Goetze Amazon.com;

“The Amarna Scholarly Tablets” by Shlomo Izre'el (1997) Cuneiform Tablets in Egypt Amazon.com;

“Digital Cuneiform” by Johannes Bergerhausen (2014) Amazon.com;

Deciphering Cuneiform

The word cuneiform — Latin for ''wedge-shaped'' — was coined by Thomas Hyde in 1700. Italian nobleman Pietro della Valle was the first to publish facsimile copies of cuneiform in 1658. The first copies from cuneiform accurate enough to form a basis for future decipherment would appear more than a century later, in 1778, the work of Carsten Niebuhr of Denmark.

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: After cuneiform was replaced by alphabetic writing sometime after the first century A.D., the hundreds of thousands of clay tablets and other inscribed objects went unread for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until the early nineteenth century, when archaeologists first began to excavate the tablets, that scholars could begin to attempt to understand these texts. One important early key to deciphering the script proved to be the discovery of a kind of cuneiform Rosetta Stone, a circa 500 B.C. trilingual inscription at the site of Bisitun Pass in Iran. Written in Persian, Akkadian, and an Iranian language known as Elamite, it recorded the feats of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great (r. 521–486 B.C.). By deciphering repetitive words such as “Darius” and “king” in Persian, scholars were able to slowly piece together how cuneiform worked. Called Assyriologists, these specialists were eventually able to translate different languages written in cuneiform across many eras, though some early versions of the script remain undeciphered. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

In the 1830's and 1840's, Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson — the ''father of Assyriology'' —copied the long cuneiform inscriptions of Darius the Great at Bisitun Pass. With three languages — and three different cuneiform scripts — to work with, Sir Rawlinson was able to present the first ''substantial, connected Old Persian text properly deciphered and reasonably translated'' of Akkadian and Elamite, William Hallo wrote in ''The Ancient Near East: A History''. The book is a standard textbook that he co-authored with William Kelly Simpson.

Translating Cuneiform

scholars at Cambridge translating cuneiform tablets

According to Archaeology magazine: Today, the ability to read cuneiform is the key to understanding all manner of cultural activities in the ancient Near East — from determining what was known of the cosmos and its workings, to the august lives of Assyrian kings, to the secrets of making a Babylonian stew. Of the estimated half-million cuneiform objects that have been excavated, many have yet to be catalogued and translated. Here, a few fine and varied examples of some of the most interesting ones that have been. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

The collection, copying, translation and publishing of cuneiform texts at Yale owe much to Albert T. Clay and J. Pierpont Morgan. In 1910 the Hartford-born financier and industrialist, who was a lifelong collector of Near Eastern artifacts, endowed a professorship of Assyriology and the Babylonian Collection at Yale, and Mr. Clay served as its first professor and curator.

Hand-copying cuneiform texts remains a mainstay of scholarship in the field. The main cuneiform language has been difficult to translate. The symbol, for example, that represented a rising sun later represented some forty words and a dozen separate syllables. The word "anshe," was first translated as "donkey" but it was so found that it could also mean a god, an offering, a chariot-pulling animal, a horse.

The Babylonian Collection at Yale houses the largest assemblage of cuneiform inscriptions in the United States and one of the five largest in the world. In fact, during Mr. Hallow's 40-year tenure as professor and curator, Yale acquired 10,000 tablets from the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York.

The University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute opened in 1919. It was heavily financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had been greatly influenced by James Henry Breasted, a passionate archaeologist. Abby Rockefeller had read his best seller “Ancient Times” to her children. Today the institute, which still has seven digs going on, boasts objects from excavations in Egypt, Israel, Syria, Turkey and Iraq. Many artifacts were acquired from joint digs with host countries with which the findings were shared. Among the institute’s prized holdings is a 40-ton winged bull from Khorsabad, the capital of Assyria, from around 715 B.C.

Deciphering Sumerian, Old Persian, Babylonian and Assyrian

Samuel Noah Kramar deciphered the Sumerian cuneiform tablets in the 19th century using Rosetta-Stone-like bilingual texts with the same passages in Sumerian and Akkadian (Akkadian in turn had been translated using Rosetta-Stone-like bilingual texts with some passages in an Akkadian-like language and Old Persian). The most important texts came from Persepolis, the ancient capital of Persia.

After the Akkadian text was deciphered, words and sounds in a hitherto unknown language, which appeared to be older and unrelated to Akkadian, were found. This led to the discovery of the Sumerian language and the Sumerian people.

Babylonian and Assyrian were deciphered after Old Persian was deciphered. Old Persian was deciphered in 1802, by George Grotefend, a German philologist. He figured out that one of the unknown languages represented by the cuneiform writing from Persepolis was Old Persian based on the words for Persian kings and then translated the phonetic value of each symbol. Early linguists decided that cuneiform was most likely an alphabet because 22 major signs appeared again and again.

Akkadian and Babylonian were deciphered between 1835 and 1847, by Henry Rawlinson, a British military officer, using the Behistun Rock (Bisotoun Rock). Located 20 miles from Kermanshah, Iran, it is one of the most important archeological sites in the world. Located at an elevation of 4000 feet high on an ancient highway between Mesopotamia and Persia, it is a cliff face carved with cuneiform characters that describe the achievements of Darius the Great in three languages: Old Persian, Babylonian and Elamatic.

Rawlinson copied the Old Persian text while suspended by a rope in front of the cliff.. After spending several years working out all Old Persian texts he returned and translated the Babylonian and Elamitic sections. Akkadian was worked out because it was a Semitic similar to Elamitic.

The Behistun Rock also allowed Rawlinson to decipher Babylonian. Assyrian and the entire cuneiform language was worked with the discovery of Assyrian “instruction manuals” and “dictionaries” found at a 7th century Assyrian site.

Restoring Cuneiform Tablets

Babylonian exercise tablet

Just getting cuneiform tablets to the point where they can be translated has also been a considerable chore. Describing what the first restorers and translators were faced with in the 19th century, David Damrosch, a professor of English at Columbia University, wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Unbaked clay tablets could crumble, and even those that had been baked, giving them the heft and durability of terra cotta tiles that have been broken amid the ruins...Tablets were often stored loose in boxes and sometimes damaged each other...A given tablet might have been broken into a dozen or more pieces that were now widely dispersed among the thousands of fragments at the museum.” One then needs the “ability to piece tablets together, a task requiring both exceptional visual memory and manual dexterity in creating “joins” of fragments.”

“Items under active consideration were laid out on planks set on trestles in a dimly lit room. In addition museums held paper “squeezes” — impressions that had been made by pressing damp paper onto inscriptions too big to move.” But there were problems here too. “The squeezes deteriorated on handling and were further damaged when mice got at them.”

Today, because so few specialists can read the ancient Sumerian and Akkadian languages, many cuneiform tablets have not been read. Many lie in packed away in storage, unlabeled. Scholars at Johns Hopkins are currently setting up a cuneiform data base in which photographs of tablets can be cased with a cuneiform keyboard.

Cuneiform Tablets as Historical Sources

Writing on the sun-baked tablets, preserved in the dry climate of Mesopotamia have survive the ravages of time better than the earliest writing of other ancient civilizations in Egypt, China, India and Peru, which used perishable materials such as papyrus, wood, bamboo, palm leaves and cotton and wool twine that have been largely lost to time. Scholars have access to more original documents from Sumer and other Mesopotamian culture than they do from ancient Egypt, Greece or Rome.

The existence of cuneiform was not known until travelers in the Near East in the early 1600s began returning home with strange "chicken scratching" that were regarded as decorations not writing. A large archives of Sumerian cuneiform records was found in sacred Nippur. Some 20,000 cuneiform tablets were discovered in a 260-room place in Mari, a major Mesopotamian trading center that was ruled by Semitic-speaking tribes. Texts from Assyrian tablets established dates of events in Israelite history and confirmed parts of the Bible.

The Journal of Cuneiform Studies is authoritative periodical on Mesopotamian writing. The University of Pennsylvania contains the world's largest collection of Sumerian cuneiform tablets. Of about 10,000 known Sumerian tablets, the University of Pennsylvania contains about 3,500 of them.

Great Ancient Mesopotamia Libraries and Troves of Cuneiform Tablets

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Of the greatest importance, both for the help it proved in the decipherment and for the interest it created in wider circles, was the fortunate fact that English excavations at Nineveh came upon the remnants of a great library collected around 600 B.C. by one of the last Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal. Historical texts from this library, as well as inscriptions found in other Assyrian palaces, threw new light upon personages and events dealt with in the Bible: occasionally Assyrian words would help the understanding of a difficult biblical idiom and, most striking of all, a story about the Deluge, remarkably similar to the biblical account, was among the finds.[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Unfortunately, the importance of the tablet find did not immediately dawn on the excavators, so no efforts were made to keep together fragments that were found together; rather everything was simply dumped in baskets. As a result, scholars to this day are hard at work piecing fragments of Ashurbanipal's library together, and the finding of a new "join" is a source of great joy and satisfaction.

The content of the library was rich and varied, ranging from literary works in the strict sense of belles-lettres, to handbook literature codifying the knowledge of the times in various arts, sciences, and pseudo-sciences. Of particular importance for the decipherment were the lexical texts found. They gave precious information about how the multi-value cuneiform signs could be read. They also contained grammatical and lexical works dealing with a new and unheard of language, ancient Sumerian. This language, which preceded Akkadian (that is Assyrian and Babylonian) as vehicle of ancient Mesopotamian culture, has no relative among known languages and would almost certainly have proved impenetrable had not the Library of Ashurbanipal provided ancient grammars, dictionaries, and — most important of all — excellent and precise translations from Sumerian to Akkadian, its many bilingual texts.

Comparable in many ways to the find of the Library of Ashurbanipal was the find to the south, in Nippur, of what was at first believed to be a temple library belonging to Enlil's famous temple there, Ekur. Further exploration has shown, however, that the tablets in question come from private houses, and it seems probable that they represent the "wastepaper baskets" of scribal schools carted over and used simply as fill in the rebuilding of private houses.

The content of these — also mostly broken and fragmentary — tablets is the early Sumerian literature as it survived in the schools, during the period when Sumerian culture was coming to an end in the first centuries of the second millennium B.C. Here too, a great task of reconstructing the works involved from fragments awaited the scholars, a task still far from complete. Besides the two large finds here described, mention should also be made of important discoveries of texts in smaller libraries in Ashur found by the German excavation there, and a later, surprising find of tablets in the mound of Sultan Tepe by an English expedition.

Unraveling Mesopotamia History from the Cuneiform Texts

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Sumer was a collection of city-states surrounded by agricultural land. As the city-states grew, so did the potential for border conflicts, such as one that raged for 200 years between Lagash and Umma, both in present-day Iraq. The Stela of the Vultures, which survives as seven fragments of what was once a six-foot slab of limestone, records Lagash’s eventual victory. One side depicts the god Ningirsu, holding his enemies in a sack, while the other shows a series of scenes from the conflict. A cuneiform account by Lagash’s leader, Eannatum, wraps around the stela: “Eannatum struck at Umma,” it reads. “The bodies were soon 3,600 in number....I, Eannatum, like a fierce storm wind, I unleashed the tempest!”

“The historical side depicts Eannatum leading a phalanx of soldiers trampling enemies underfoot, a victory parade, a funeral ceremony, and another, poorly preserved tableau — along with, at top, the image that gives the stela its name, a kettle of vultures consuming the heads of Umma soldiers. It is, in a way, a document both poetic and legal — it invokes the grace and power of Ningirsu, and stakes a claim to land won by force.

“Lagash’s primacy was short-lived. By the end of the period, Umma had plundered its rival and begun the consolidation of power that would result in the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The tradition of documenting battles in words and pictures continued, perhaps reaching a peak with the Assyrians in the seventh century B.C., when they carved elaborate battle reliefs in the North Palace of Nineveh in present-day Iraq, and documented the siege of Jerusalem on a series of octagonal clay prisms called Sennacherib’s Annals.

Though Akkadian as a spoken language in Mesopotamia died out toward the end of the first millennium B.C., cuneiform continued to be used by temple scribes and astrologers. Greek scholars are known to have flocked to Babylon during this time to learn astronomy, and excavated tablets inscribed in both Greek and Akkadian show that at least a few of these visiting astronomers even tried to master the art of writing cuneiform. But the end was near. The last known tablets that can be dated were written in the late first century A.D. Some scholars believe cuneiform ceased to be used around that time, but Assyriologist Markham Geller of the Free University of Berlin believes it endured for another two centuries. He points to classical sources that mention that Babylonian temples continued to thrive, and believes that they would have maintained scribes still capable of reading and writing cuneiform to ensure that rituals were properly performed. He also thinks cuneiform medical texts may have continued to be used to diagnose illnesses during this era.

Laments on the ruin of Ur

“But in the third century A.D., the neighboring Sassanian Empire, known to be hostile to foreign religions, seized Babylon. “They shut the temples down,” says Geller, “and they sent everyone home.” He believes it was only when the very last of these temple scribes died that the rich, 3,000-year-old cuneiform record finally fell silent.

Using AI to Read Ancient Cuneiform Tablets

The Electronic Babylonian Library Platform (eBL) is an artificial intelligence (AI) platform used to read cuneiform tablets. In 2023: Enrique Jiménez wrote: The primary objective of the eBL project is to advance the understanding of Babylonian literature by reconstructing it to the fullest extent possible. Additionally, the project aims to provide a user-friendly platform containing extensive transliterations of cuneiform tablet fragments, along with a robust search tool, to address the abiding problem of the fragmented nature of Mesopotamian literature. [Source: Enrique Jiménez, Chair of Ancient Near Eastern Literatures, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, The Conservation, May 25, 2023]

The backbone of the project is the Fragmentarium, which digitally brings together transliterations of fragments of cuneiform tablets. These cuneiform tablets were mostly excavated in the 19th century, and have been stored in the drawers of various museums since. In particular, the British Museum holds hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets, many of which have not been read since antiquity. Our collaboration with the British Museum has digitised tens of thousands of these tablets, and transliterated them in the Fragmentarium.

If the Fragmentarium is the backbone of the project, its showcase is the eBL Corpus. The corpus is conceived to contain editions of all “classics” of Babylonian literature copied during the first millennium BCE, from the Epic of Creation to the Poem of the Righteous Sufferer.The eBL editions use many previously unpublished or unedited fragments, often identified by the members of the project, and thus represent cutting-edge versions of the texts.

The main problem we face is getting these two large textual databases (Fragmentarium and Corpus) to talk to each other. The literature from ancient Mesopotamia is still riddled with textual gaps, and the identification of fragments to fill these gaps has traditionally been slow and laborious due to the ambiguities of cuneiform script.Indeed, cuneiform writing knows no orthography. When there is sufficient context, then multiple meaning is not a problem: usually there is only one correct reading for each sign. In a recent project, we trained an AI model with a relatively small corpus (less than 20,000 lines) and without using a sign list, to make this multiple meaning clear… The computer achieved a success rate of 98 percent..

With isolated fragments, however, there is no correct reading of a character. The reading only becomes possible if one identifies where the fragment comes from. Also, we do not have a single complete cuneiform tablet from which to reconstruct the beginning of a work like Gilgamesh. Instead, we possess a multitude of manuscripts, some of which overlap. Typically, only a few fragments of each manuscript survive. The key to identifying additional pieces, and thus to advancing the reconstruction, lies in discovering overlaps between fragments, which will, in turn, enable the discovery of further overlaps with other fragments, and so on.

Interestingly, the substitutions encountered in cuneiform texts bear resemblance to genetic variations found in DNA. Taking into account such variations is a central concern in bioinformatics, which has lead to the development of numerous sequence alignment algorithms. The eBL project has implemented similar string alignment algorithm specifically tailored for cuneiform, facilitating the identification process and significantly speeding up progress. Using this algorithm, and the various other utilities that the eBL project has made available to researchers, the team dedicated to it at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich has succeeded in identifying thousands of new fragments and significantly advanced the reconstruction of Babylonian literature.

If the 150 years of existence of Assyriology prior to the project found 5,000 cuneiform pieces that could be joined to already known pieces, the five years of the eBL project have added another 1,500 to the tally, and several thousand that cannot be joined directly. The pace is only accelerating, and it is hoped that following the publication of the electronic Babylonian Library portal in February, other researchers and amateurs will use these tools to reconstruct partly lost ancient texts.

Archaeologists Use AI to Instantly Translate 4,500-Year-Old Cuneiform Tablets

A team of archaeologists and computer scientists have created an artificial intelligence (AI) program that can instantly translate ancient cuneiform tablets using neural machine learning translations. In n a paper published in June 2023 in the journal PNAS Nexus, from the Oxford University Press, researchers applied the AI program to translate 4,500-year-old Akkadian texts with a high level of accuracy. [Source: Mark Milligan, Heritage Daily, June 22, 2023]

Heritage Dail reported: Akkadian is an ancient East Semitic language once spoken in various regions of ancient Mesopotamia, including Akkad, Assyria, Isin, Larsa, Babylonia, and possibly Dilmun. The language is preserved on clay tablets dating back to 2500 B.C. written using cuneiform. According to the researchers: “Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets inscribed in the cuneiform script document the political, social, economic, and scientific history of ancient Mesopotamia. Yet, most of these documents remain untranslated and inaccessible due to their sheer number and limited quantity of experts able to read them.”

The AI program has a high level accuracy when translating formal Akkadian texts such as royal decrees or omens that follow a certain pattern. More literary and poetic texts, such as letters from priests or tracts, were more likely to have “hallucinations” – an AI term meaning that the machine generated a result completely unrelated to the text provided. The goal of the neural machine translation (NMT) into English from Akkadian is to be part of a human–machine collaboration, by creating a pipeline that assists the scholar or student of the ancient language. Currently, the NMT model is available on an online notebook and the source code has been made available on GitHub at Akkademia. The researchers are currently developing an online application called the Babylonian Engine.

According to the Times of Israel: Neural machine translation, also used by Google Translate, Baidu translate, and other translation engines, works by converting words into a string of numbers, and uses a complex mathematical formula, called a neural network, to output a sentence in another language in a more accurate and natural sentence construction than translating word-for-word. [Source: Melanie Lidman, Times of Israel, June 17, 2023]

“What’s so amazing about it is that I don’t need to understand Akkadian at all to translate [a tablet] and get what’s behind the cuneiform,” said Gai Gutherz, a computer scientist who was part of the team that developed the program. “I can just use the algorithm to understand and discover what the past has to say.”The project began as a thesis project for Gutherz’s masters degree at Tel Aviv University. In May, the team published a research paper in the peer-reviewed PNAS Nexus, from the Oxford University Press, describing its neural machine translation from Akkadian to English.

There are tens of thousands of untranslated cuneiform tablets. “Translating all the tablets that remain untranslated could expose us to the first days of history, to the civilization of those people, what they believed in, what they were talking about, what they were documenting,” said Gutherz.

cuneiform cookies made by Esther Brownsmith

Making Cuneiform Tablet Cookies

Gingerbread cookies shaped like cuneiform tablets baked by Katy Blanchard of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology launched somewhat of an archaeo-culinary craze online. In ancient times cuneiform tablets were made pressing a reed stylus into clay. Jennifer A. Kingson wrote in the New York Times: Ms. Blanchard, whose passions are archaeology and baking, used chopsticks, a fish knife and a gingerbread recipe that came packaged with a Coliseum-shaped cookie-cutter she once bought. Not only did her cuneiform cookies beguile her colleagues at the office party, they also gained some measure of internet renown after a Penn Museum publicist posted an article about how she made them. (Sample comment from the public: “Mine will probably taste more like the Dead Sea Scrolls.”) [Source: Jennifer A. Kingson, New York Times November 14, 2016]

From there, cuneiform cookies started to become — as the newspaper The Forward put it — “a thing.” Bloggers were enthralled, including one who said she was taking a class in Hittite and opted to practice on shortbread. (“The writing took a surprisingly long time,” she observed.)The archaeo-culinary trend also exposed an odd subculture of people who are consumed with ancient languages, like the guy who uses the Twitter handle @DumbCuneiform and runs a business that will translate your tweets and texts into cuneiform characters and etch them in a hand-held tablet. (No, you cannot make this stuff up.) “It really struck the world in just the right nerdy place,” said Ms. Blanchard, noting that a number of people, including home schooling parents, classroom teachers and scholars of ancient languages, had taken the idea and run with it. “People have made some amazing tablets, much more complete and creative than mine,” Ms. Blanchard said. “Some people made full sentences. Mine just say, ‘God,’ ‘build,’ ‘bird’ and ‘sun.’”

Ms. Blanchard’s title at the museum is “keeper,” which involves caring for the artifacts in the Near Eastern collections and helping visiting researchers and scholars find the right items to advance their work. “It’s a combination of putting small things in boxes and knowing where jars of dirt came from,” as she put it once in an interview. The cuneiform tablets are in the Babylonian collection, which is not in her purview, but they inspired her nonetheless.

It was a holiday party several years ago that prompted Ms. Blanchard to contemplate the similarities between clay tablets and cookie dough. She has been making cuneiform cookies annually ever since, usually for the same holiday party. “Last year, I tried to make a brownie ziggurat,” modeled on an ancient temple, “but it did not go over as well,” she said. Although Ms. Blanchard surmises that shortbread might also be a good medium for cuneiform, it was the gingerbread that went viral, inspiring copycats online.

Inspired by Ms. Blanchard’s cuneiform cookies, Esther Brownsmith, a Ph.D. student in the Bible and Near East program at Brandeis University who has been studying Akkadian for years, went all out: For a New Year’s party, she baked four tablets of gingerbread, each on a 13-by-18-inch pan, and copied part of the Enuma Elish, a seven-tablet Babylonian creation myth, onto them. A stunning step-by-step description of this feat has drawn thousands of “likes” on her Tumblr blog.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024