Home | Category: Life, Families, Women

MESOPOTAMIA FURNITURE

The Sumerians used mats made of dry stalks and tendrils to cover dust and stone floors. They had wooden furniture. The first mirrors were no doubt puddles, ponds and lakes with still water. By 3500 B.C. mirrors were fashioned from polished metal in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians made mirrors with ivory, wood and gold handles.

In upper class Babylonian houses, The floor was covered with rugs, for the manufacture of which Babylonia was famous, and chairs, couches, and tables were placed here and there. The furniture was artistic in form; a seal-cylinder, of the age of Ur-Bau, King of Ur, the older contemporary of Gudea, represents a chair, the feet of which have been carved into the likeness of those of oxen. If we may judge from Egyptian analogies the material of which they were formed would have been ivory. The Assyrian furniture of later days doubtless followed older Babylonian models, and we can gain from it some idea of what they must have been like. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The chairs were of various kinds. Some had backs and arms, some were mere stools. The seats of many were so high that a footstool was required by those who used them. The employment of the footstool must go back to a considerable antiquity, since we find some of the Tel-el-Amarna correspondents in the fourteenth century before our era comparing themselves to the footstool of the King. Chairs and stools alike were furnished with cushions which were covered with embroidered tapestries. So also were the couches and bedsteads used by the wealthier classes. The poor contented themselves with a single mattress laid upon the floor, and since everyone slept in the clothes he had worn during the day, rising in the morning was not a difficult task. The tables had four legs, and the wood of which they were composed was often inlaid with ivory.

Wood inlaid with ivory and other precious materials was also employed for the chairs and sofas. Tripods of bronze, moreover, stood in different parts of the room, and vases of water or wine were placed upon them. Fragments of some of them have been found in the ruins of Nineveh, and they are represented in early Babylonian seals. The feet of the tripod were artistically shaped to resemble the feet of oxen, the clinched human hand, or some similar design. At meals the tripod stood beside the table on which the dishes were laid. Those who eat sat on chairs in the earlier period, but in later times the fashion grew up, for the men at any rate, to recline on a couch. Assur-bani-pal, for example, is thus represented, while the Queen sits beside him on a lofty chair. Perhaps the difference in manners is an illustration of the greater conservatism of women who adhere to customs which have been discarded by the men.

What the chairs, tables, footstools, and couches were like may be seen from the Assyrian bas-reliefs. They were highly artistic in design and character, and were of various shapes. The tables or stands sometimes had the form of camp-stools, sometimes were three-legged, but more usually they were furnished with four legs, which occasionally were placed on a sort of platform or stand. At times they were provided with shelves. Special stands with shelves were also made for holding vases, though large jars were often made to stand on tripods.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Painting Pots – Painting People: Late Neolithic Ceramics in Ancient Mesopotamia”

by Walter Cruell, Inna Mateiciucova, et al. | Feb 28, 2017 Amazon.com;

“II Workshop on Late Neolithic Ceramics in Ancient Mesopotamia: Pottery in Context”

by Anna Gómez Bach, Jörg Becker, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pottery from Tell Khaiber: A Craft Tradition of the First Sealand Dynasty: 1" (Archaeology of Ancient Iraq) by Daniel Calderbank (2021) Amazon.com;

“Lithic Technology of Neolithic Syria” (BAR Archaeopress) by Yoshihiro Nishiaki (2000) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Art, Objects from Ur and Al-'Ubaid” by The British Museum and Terence C. Mitchell (1969) Amazon.com;

“Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur” by Richard L. Zettler and Lee Horne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs” by Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, McGuire Gibson (2016) Amazon.com;

“An Examination of Late Assyrian Metalwork: with Special Reference to Nimrud”

by John Curtis (2013) Amazon.com

“The Published Ivories from Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud” by Georgina Herrmann , H. Coffey, et al. (2004) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Households in Ancient Mesopotamia”: Papers Read at the 40th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, July 5-8, 1993 (Pihans) Paperback – Illustrated, December 31, 1996 by KR Veenhof Amazon.com;

“The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by Jean Dethier (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Rental Houses in the Neo-Babylonian Period (VI-V Centuries BC)” by Stefan Zawadzki (2018) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud: Volume VI - Documents from the Nabu Temple and from Private Houses on the Citadel” by S Herbordt, R Mattila, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

Ancient Mesopotamian Household Items

stuff from Uruk

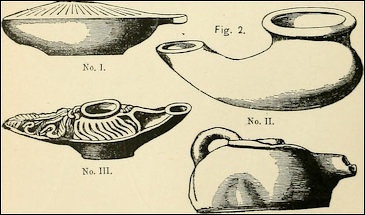

The earliest lamps were made from sea shells. These were observed in Mesopotamia. Lamps made from man-made materials such as earthenware and alabaster appeared between 3500 and 2500 B.C. in Sumer, Egypt and the Indus Valley. Metal lamps were rare. As technology advanced a groove for the wick was added, the bottom of the lamp was titled to concentrate the oil and the place where the flame burned was moved away from the handle. Mostly animal fats and vegetable and fish oils were burned. In Sumer, seepage from petroleum deposits was used. The wicks were made from twisted natural fibers.

A makaltu was a shallow bowl. Found in dowry lists and in instructions for offerings as well as recipes. It is like a like a pie plate, and usually made of wood. Vases of stone and earthenware, of bronze, gold, and silver, were plentifully in use. A vase of silver mounted on a bronze pedestal with four feet, which was dedicated to his god by one of the high-priests of Lagas, has been found at Tello, and stone bowls, inscribed with the name of Gudea, and closely resembling similar bowls from the early Egyptian tombs, have also been disinterred there. A vase of Egyptian alabaster, discovered by the French excavators in Babylonia, but subsequently lost in the Tigris, bore upon it an inscription stating it to have been part of the spoil obtained by Naram-Sin, the son of Sargon of Akkad, from his conquest of the Sinaitic peninsula. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In Assyrian days the vases were frequently of porcelain or glass; when these were first introduced is still unknown. Various articles of furniture are mentioned in the later contracts. Under Nabonidos, 7 shekels, or 21 shillings, were given for a copper kettle and cup, the kettle weighing 16 manehs (or 42 pounds troy) and the cup 2 manehs (5 pounds 7 ounces troy). These were left, it may be noted, in the safe-keeping of a slave, and were bought by a lady. At a later date, in the third year of Cambyses, as much as 4 manehs 9 shekels, or £36 7s., were paid for a large copper jug and qulla, which was probably of the same form as the qullas of modern Egypt. The female slave who seems to have started an inn in the sixth year of Cambyses provided herself with five bedsteads, ten chairs, three dishes, one wardrobe (?), three shears, one iron shovel, one syphon, one winedecanter, one chain (?), one brazier, and other objects which cannot as yet be identified.

The brazier was probably a Babylonian invention. At all events we find it used in Judah after contact with Assyria had introduced the habits of the farther East among the Jews (Jer. xxxvi. 22), like the gnomon or sun-dial of Ahaz (Is. xxxvIII. 8), which was also of Babylonian origin (Herod., II., 109). The gnomon seems to have consisted of a column, the shadow of which was thrown on a flight of twelve steps representing the twelve double hours into which the diurnal revolutions of the earth were divided and which thus indicated the time of day.

Metal Objects

Many of the articles of daily use in the houses of the people, such as knives, tools of all kinds, bowls, dishes, and the like, were made of copper or bronze. They were, however, somewhat expensive, and as late as the reign of Cambyses we find that a copper libation-bowl and cup cost as much as 4 manehs 9 shekels, (£37 7s.), and about the same time 22 shekels (£3 3s.) were paid for two copper bowls 7½ manehs in weight. If the weight in this case were equivalent to that of the silver maneh the cost would have been nearly 4d. per ounce. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

It must be remembered that, as in the modern East, the workman expected the metal to be furnished by his customer; and accordingly we hear of 3 manehs of iron being given to a smith to be made into rods for bows. Three manehs of iron were also considered sufficient for the manufacture of six swords, two oboe-rings, and two bolts. All this, of course, belongs to the age of the second Babylonian empire, when iron had taken the place of bronze.

In the age of the Egyptian empire in Asia, at the beginning of the seventeenth century B.C., iron was passing into general use. Objects of iron are referred to in the inscriptions, and a couple of centuries later we hear of iron chariots among the Canaanites, and of ironsmiths in Palestine, who repair the shattered vehicles of Egyptian travellers in that country. It must have been at this time that the bronzesmith in Babylonia became transformed into an ironsmith.

Oil and Daily Life

Lamps for the ancient Near East

Harry A. Hoffner, Jr wrote in “Oil in Hittite Texts”: “Oil was one of the minimal essentials in ancient Near Eastern life. This has been noted in connection with ancient Israel, but it is also true in Hittite Anatolia. That being the case, oil is included among the elementary needs of the poor which compassionate people are enjoined to meet. Several texts whose composition goes back to the Old Hittite period mention this: to the hungry give bread, to the thirsty water, to the naked clothes, to the dried out/desiccated. The same situation is reflected in a passage from the new Hurro-Hittite bilingual, where the god Teshub is poor and must be helped by his fellow deities. They give food to the hungry god, clothes to the naked god, and oil to the hurtant- god. [Source: Harry A. Hoffner, Jr., “Oil in Hittite Texts,” Internet Archive, from Emory/Biblical Archaeology /=/]

“Oil in Hittite texts can be from an animal or a vegetable source. Oil from plants includes olive oil, sesame oil, cypress (or juniper) oil/resin, and oil extracted from nuts. Oil from animals includes lard (i.e., oil/fat from pigs) and sheep fat. One of the principal uses of oil in ancient times was as a fuel for lamps or torches. The texts, however, offer little evidence for this. Only recently, with the discovery of the syllabic writing of the principal Hittite word for "oil," sagn-, has it become possible to recognize that the meaning of the adjective sakuwant- frequently modifying torches (GISzuppari) is "oil-soaked" (Hoffner 1994). The construction of a Hittite torch is unclear. It might have consisted of a stick with the upper end wrapped in cloth, in which case the cloth would have been soaked in oil as fuel. [Source: Harry A. Hoffner, Jr., “Oil in Hittite Texts,” Internet Archive, from Emory/Biblical Archaeology /=/]

“Lamps were called (DUG)sasanna, It is possible that the wick was called lappina-. Only two passages give any indication of lamp fuel:"two measuring vessels of butter/ghee for lamps" and "They set out in front of the bones a lamp[É] of [x] shekels (filled) with fine oil." There are other references to the burning of oil. A mixture of honey and oil was burned to produce a pleasant odor for the gods which by smelling the same they could be said to eat and drink. Another ritual text also mentions burning cedar, í.NUN, honey, and other materials to produce a sweet odor. In still another passage, honey and olive oil are poured into a clay cup and a tiny chip of wood floating on the surface is ignited and burns, perhaps absorbing the oil in which it floats like a wick.”/=/

See Separate Article: HITTITE LIFE, FOOD, OIL, WATER AND POTTERY africame.factsanddetails.com

First Air Conditioning and Bedrooms

The first known bedrooms were in a Sumer palace, dated to 3500 B.C. In Sumerians homes there was usually only one bedroom irregardless of the size of the size of the family and household. The master of the house usually slept in the bedroom while family members and servants slept on couches and longues and on the floor in other rooms scattered around the house. There were pillows but they were usually made from wood, ivory or alabaster and they designed primarily to keep elaborate hairdos from getting messed up.

A wealthy Babylonian merchant used ice in 2000 B.C. to make the world's first air-conditioned house. The ice was made using a technique discovered by the Egyptian as early as 3000 B.C. that takes advantage of a natural phenomena that occurs in dry climates. Shallow trays of water left out at night in shallow clay trays on a bed of straw would freeze as a result of evaporation into the dry air and sudden temperatures drops even though the temperature was well above freezing. People also sprayed water on exposed walls and floors, with the evaporation producing a cooling effects.

The air was excluded by means of curtains which were drawn across them when the weather was cold or when it was necessary to keep out the sunlight.The apartments of the women were separate from those of the men, and the servants slept either on the ground-floor or in an outbuilding of their own. The furniture, even of the palaces, was scanty from a modern point of view. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024