Home | Category: Life, Families, Women

DIVORCE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

There are records of divorce trials in Babylonian and Assyrian cuneiform libraries. Under the Code of Hammurabi a woman could get a divorce and keep her dowry, property and children and get child support if she could prove her husband "degraded" her. Legally, a second marriage invalidated the first, if the first wife was still alive. This was surprising considering polygamy was allowed.

Divorce was optional with the man, but he had to restore the dowry and, if the wife had borne him children, she had the custody of them. He had then to assign her the income of field, or garden, as well as goods, to maintain herself and children until they grew up. She then shared equally with them in the allowance (and apparently in his estate at his death) and was free to marry again. If she had no children, he returned her the dowry and paid her a sum equivalent to the bride-price, or a mina of silver, if there had been none. The latter is the forfeit usually named in the contract for his repudiation of her. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

If she had been a bad wife, the Code allowed him to send her away, while he kept the children and her dowry; or he could degrade her to the position of a slave in his own house, where she would have food and clothing. She might bring an action against him for cruelty and neglect and, if she proved her case, obtain a judicial separation, taking with her her dowry. No other punishment fell on the man. If she did not prove her case, but proved to be a bad wife, she was drowned. If she were left without maintenance during her husband's involuntary absence, she could cohabit with another man, but must return to her husband if he came back, the children of the second union remaining with their own father. If she had maintenance, a breach of the marriage tie was adultery. Wilful desertion by, or exile of, the husband dissolved the marriage, and if he came back he had no claim on her property; possibly not on his own.

As a widow, the wife took her husband's place in the family, living on in his house and bringing up the children. She could only remarry with judicial consent, when the judge was bound to inventory the deceased's estate and hand it over to her and her new husband in trust for the children. They could not alienate a single utensil. If she did not remarry, she lived on in her husband's house and took a child's share on the division of his estate, when the children had grown up. She still retained her dowry and any settlement deeded to her by her husband. This property came to her children. If she had remarried, all her children shared equally in her dowry, but the first husband's gift fell to his children or to her selection among them, if so empowered.

We do not know the reasons which were considered sufficient to justify divorce. The language of the early laws would seem to imply that originally it was quite enough to pronounce the words: “Thou art not my wife,” “Thou art not my husband.” But the loss of the wife's dowry and the penalties attached to divorce must have tended to check it on the part of the husband, except in exceptional circumstances. Perhaps want of children was held to be a sufficient pretext for it; certainly adultery must have been so.Another cause of divorce was a legal one: a second marriage invalidated the first, if the first wife was still alive. This is a very astonishing fact in a country where polygamy was allowed. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Tying the Knot: Marriage Customs in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“Sacred Marriages: The Divine-Human Sexual Metaphor from Sumer to Early Christianity”

by Martti Nissinen and Risto Uro (2008) Amazon.com;

"The Sumerian Sacred Marriage in the Light of Comparative Evidence" (State Archives of Assyria Studies) by Pirjo Lapinkivi (2004) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Households in Ancient Mesopotamia”: Papers Read at the 40th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, July 5-8, 1993 (Pihans) Paperback – Illustrated, December 31, 1996 by KR Veenhof Amazon.com;

“Birth in Babylonia and the Bible” by Marten Stol (2000) Amazon.com;

“Law and Gender in the Ancient Near East and the Hebrew Bible” by Ilan Peled (2019) Amazon.com;

“Women of Babylon” by Zainab Bahrani Amazon.com;

“Women of Assur and Kanesh: Texts from the Archives of Assyrian Merchants” by Cécile Michel (2020) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

Divorced Women

The divorced wife was regarded by the law as a widow, and could therefore marry again. A deed of divorce, dated in the reign of the father of Khammurabi, expressly grants her this right. To the remarriage of the widow there was naturally no bar; but the children by the two marriages belonged to different families, and were kept carefully distinct. This is illustrated by a curious deed drawn up at Babylon, in the ninth year of Nabonidos. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

A certain Bel-Katsir, who had been adopted by his uncle, married a widow who already had a son. She bore him no children, however, and he accordingly asked the permission of his uncle to adopt his step-son, thereby making him the heir of his uncle's property. To this the uncle objected, and it was finally agreed that if BelKatsir had no child he was to adopt his own brother, and so secure the succession of the estate to a member of his own family.

The property of the mother probably went to her son; but she had the power to leave it as she liked. This may be gathered from a will, dated in the seventh year of Cyrus, in which a son leaves property to his father in case of death, which had come to him from his maternal grandfather and grandmother. The property had been specially bequeathed to him, doubtless after his mother's death, the grandmother passing over the rest of her descendants in his favor.

Divorce and Laws Recognizing Women as Possessions of Their Husbands

There are records of divorce trials in Babylonian and Assyrian cuneiform libraries. Under the Code of Hammurabi a woman could get a divorce and keep her dowry, property and children and get child support if she could prove her husband "degraded" her.

Morris Jastrow said: “The Code still recognises the wife as an actual possession of her husband, but, on the other hand, if he fails to provide for her support, she may leave him. A fine distinction is made between actual desertion or enforced absence on the part of the husband. In the former case, the woman has the right to marry another, and her husband on his return not only cannot force her to return to him, but she is not permitted to do so. On the other hand, if her husband is taken prisoner and no provision has been made for her sustenance, she may marry another, but on her husband’s return he may claim her, though the children bom in the interim belong to the actual father.[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Inasmuch as the wife forms part of her husband’s chattels, divorce lies, of course, at the option of the husband, but he cannot sell his wife, and, if he dismisses her, she is to receive again her marriage portion. Alimony was allowed for her own needs and those of her children, whose rearing was committed to her. When the children reach their majority, a portion of their inheritance must be given to the mother. Even in the case of a wife who has not borne her husband any children, he may not dismiss her without giving her alimony and returning her dowry, but if she has neglected her husband’s household, and as the law expresses it, has committed “indiscretions,” he may send her away without any compensation or may even keep her as a slave, while he is free to marry another woman as his chief wife. The dawning at least of the wife’s liberty is to be seen in the provision that, if a woman desires to be rid of her husband, and provided on examination it is shown that she has good cause—the legal language implies a neglect of marital duties on the husband’s part,—she may return to her father’s house, and be entitled to her marriage portion.

“If, however, of her own accord the widow leaves her husband’s house, then she is naturally entitled to her own dowry only, and not to any share in her husband’s estate; but, on the other hand, she is free in that case to marry whomsoever she pleases. Daughters are given a share in their father’s estate, and this is extended even to those who as priestesses have taken the vow of chastity. Such nuns have a right to their dowry, which they can dispose of as they see fit, but their share of the paternal estate cannot be disposed of by them. On the death of a nun, her share reverts to her brothers or to their heirs.

“Lastly, as an interesting example of an older law, dating from the period when a man could dispose of his wife and children as he disposed of his chattels and possessions, but so modified as to be practically abrogated, we may instance the provision that, if a man pledges, or actually sells his wife and children for his debts, the creditor can claim them for three years only. In the fourth year they must be set free. This stipulation assumes an older law, according to which a man could sell his wife and children without condition. Instead of revoking the law (which, as has been pointed out, is not the usual mode of procedure in ancient legislation), the limitation of three years is inserted, and this changes the sale into a lease. We have a parallel in the Book of the Covenant (Exodus xxi., 2) which provides that a Hebrew slave must be set free after six years. This is practically an abrogation of slavery by converting it into a lease for a limited period.”

Mesopotamian Laws That Protect Women

Morris Jastrow said:“As a protection to the wife, a formal marriage contract must be drawn up, as is not infrequent in our days. A marriage without a contract is void. A woman betrothed to a man is regarded as his wife, and in case she is disgraced by another, the offender is put to death; from which we may perhaps be permitted to conclude that if she be not betrothed, the offender is obliged to marry her. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Legal rights are assured to a woman even after her husband’s death. Her children have no claim on property given to her by her husband. She may dispose of such property to a favourite child but, on the other hand, she is restrained from passing it on to her brother, which would take it out of her husband’s clan. Finally, there is a touch almost modem in the law that a wife cannot contract obligations in her husband’s name, nor can he be held responsible for debts thus contracted. The interesting feature of the provision is that it points to the independent legal status acquired by woman, who, as we learn also from business and legal documents, could own property in her own right, borrow money and contract debts independently, as long as she did not involve her husband’s property, and could appear as a witness in the courts. The dowry of a wife who dies without issue reverts to her father’s estate.

“Perhaps the most significant of these marriage-laws is the stipulation that the woman who is smitten with an incurable disease—the term used may have reference to leprosy—must be taken care of by her husband as long as she lives. In no circumstances, it is added, can he divorce her, and if she prefer to return to her father’s home, he must give her dowry to her.”

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 137-143: Divorce

If a man wish to separate from a woman who has borne him children, or from his wife who has borne him children: then he shall give that wife her dowry, and a part of the usufruct of field, garden, and property, so that she can rear her children. When she has brought up her children, a portion of all that is given to the children, equal as that of one son, shall be given to her. She may then marry the man of her heart. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

If a man wishes to separate from his wife who has borne him no children, he shall give her the amount of her purchase money and the dowry which she brought from her father's house, and let her go.

If there was no purchase price he shall give her one mina of gold as a gift of release.

If he be a freed man he shall give her one-third of a mina of gold.

If a man's wife, who lives in his house, wishes to leave it, plunges into debt, tries to ruin her house, neglects her husband, and is judicially convicted: if her husband offer her release, she may go on her way, and he gives her nothing as a gift of release. If her husband does not wish to release her, and if he take another wife, she shall remain as servant in her husband's house.

If a woman quarrel with her husband, and say: "You are not congenial to me," the reasons for her prejudice must be presented. If she is guiltless, and there is no fault on her part, but he leaves and neglects her, then no guilt attaches to this woman, she shall take her dowry and go back to her father's house.

If she is not innocent, but leaves her husband, and ruins her house, neglecting her husband, this woman shall be cast into the water.

Penalties for Breaking Marriage Contract

The dowry had to be paid to the husband, to be deposited, as it were, in his “hand.” It was with him that the marriage contract was made. This must surely go back to an age when the marriage portion was really given to the bridegroom, and he had the same right over it as was enjoyed until recently by the husband in England. Moreover, the right of divorce retained by the husband, like the fact that the bride was given away by a male relation, points in the same direction. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

According to an early Sumerian law, while the repudiation of the wife on the part of the husband was punishable only with a small fine, for the repudiation of the husband by the wife the penalty was death. A deed drawn up in the time of Khammurabi shows that this law was still in force in the age of Abraham. It lays down that if the wife is unfaithful to her husband she may be drowned, while the husband can rid himself of his wife by the payment only of a maneh of silver.

Indeed, as late as the time of Nebuchadnezzar, the old law remained unrepealed, and we find a certain Nebo-akhi-iddin, who married a singing-woman, stipulating in the marriage contract that if he should divorce her and marry another he was to pay her six manehs, but if, on the contrary, she committed adultery, she should be put to death with “an iron sword.” In this instance, however, the husband married beneath him, and in view of the antecedents of the wife the penalty with which she was threatened in case of unfaithfulness was perhaps necessary. She came to him, moreover, without either a dowry or family relations who could give her away. She was thus little better than the concubines whom the Babylonian was allowed to keep by the side of his lawful wife. But even so, the marriage contract had to be made out in full legal form, and the penalty to be paid for her divorce was as much as £54. With this she could have lived comfortably and probably have had no difficulty in finding another husband.

Mesopotamian Divorce Documents

A New Sumerian divorce settlement, dated to about 2038-1990 B.C., reads: Final judgment; Lu-Utu, the son of Nig-Baba, divorced Geme-Enlil. Dugidu, an officer and official, took oath that Geme-Enlil had taken her stand [literally "Had set her face"] (and) said, ' By the kingi Give me IO shekels of silver (and) I will not enter claim against you," (and) that she made him forfeit IO shekels of silver. Ur-.. (was) the deputy; Ur-Lama (was) the governor. The year Harshi and Humurti were sacked.[last year of Shulgi, king of Ur, about 2038-1990 B.C.] [Source: Translator: Theophile J. Meek, published by Fr. Thureau-Dangin, Recueil de tablettes Chaldennes (1903), most recently translated by C.,J. Gadd, A Sumerian Reading- Book (1924), p. 173.]

An Old Assyrian divorce document starts with the seals of six persons, each preceded by "The seal of" and then reads: “Hashusharna, the son of Gudgariya, divorced his wife, Taliya. If Taliya tries to reclaim her (former) husband Hashusharna, she shall pay 2 minas of silver and they shall put her to death in the open. If Gudgariya[1] and Hashusharna try to reclaim Taliya, they shall pay 2 minas of silver and they shall put them to death in the open.” [Source: Translator: Theophile J. Meek, Published by Fr. Thureau-Dangin, Lettres et contrats de l’epoque de la premi?r dynastie babylonienne (1910), No. 242; discussed at length by J. Lewy, ZA,m XXXVI (1925), 139-161]

A Mesopotamian abrogation of marriage agreement from Alalakh, dated to the 15th century B.C., begins with the Seal of Niqmepa (seal impression of Idrimi) and goes “Shatuwa son of Zuwa, citizen of Luba, asked Apra for (the hand of) his daughter to be his daughter-in-law, and, in accordance with the rules of Aleppo, brought him the marriage gift. Apra (subsequently) committed treason, was executed for his crime, and his estate was confiscated by the palace. Shatuwa came, in the light of his (rights to his) possessions—six ingots of copper and two bronze daggers—and took them (back). And as of this day, Niqmepa (is considered to have) satisfied Shatuwa. For (all) future time, Shatuwa [will have no further] legal claim with reference to his pos[sessions]. Seven witnesses, including the scribe. [Source: Translator: J.J. Finkelstein, Text: D. J. Wiseman, The Alalakh Tablets, No. 17, Pl. IX; transliteration and translation, p. 40]

An Ugaritic document of manumission and marriage reads: “As of this day, before witnesses, Gilben, chamberlain of the queen's palace, set free Eliyawe his maidservant, from among the women of the harem, and by pouring oil on her head, made her free, (saying:) "Just as I am quit towards her, so is she quit towards me, forever." Further, Buriyanu, the namu,[literally "man of the steppe," possibly a migrant agricultural laborer] has taken her as his wife, and Buriyanu, her husband has rendered 20 (shekels) of silver into the hands of Gilben. Four witnesses. (Inscribed on seal:) Should Buriyanu, tomorrow or the following day, refuse to consummate(his marriage) with Eliyawe — [The penalty is left unstated, and was to be understood] [Source: Translator: J.J. Finkelstein, Text. RS 8.208. F. Thureau-Dangin, Syria, XVIII (l937); 246, transliteration and translation, ibid., 253f.]

Contract for Divorce, Third year of Nabonidus, 552 B.C.: “Na'id-Marduk, son of Shamash-balatsu-iqbi, will give, of his own free-will, to Ramua, his wife, and Arad-Bunini, his son, per day four qa of food, three qa of drink; per year fifteen manas of goods, one pi sesame, one pi salt, which is at the store-house. Na'id-Marduk will not increase it. In case she flees to Nergal [i.e., she dies], the flight shall not annul it. (Done) at the office of Mushezib-Marduk, priest of Sippar.” [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276]

The above document, which bears the date of the third year of Nabonidus, is apparently a legal divorce, in which the wife is granted alimony. The marriage contracts, given above under VIII, make it unnecessary further to illustrate the workings of Babylonian divorce laws. In VIII, I, the bride was a slave, and at her marriage was given, apparently by her husband, a small sum of money and her freedom. He might, therefore, divorce her by giving her a small alimony of ten shekels; but if she divorces him, she was to be put to death. This contract was not peculiar to the early period of its date, but has parallels in the later period in the case of brides who were slaves. In VIII, 2, the case is different. The husband purchased a free bride; hence, if he divorced her, he must give her an alimony six times as great as that given to the emancipated slave of the previous contract. In VIII, 3, the bride received a dowry, so that no provision for divorce was necessary, since, as the court decisions given below prove, the dowry was always the property of the wife. In case of her divorce the husband lost it, hence this was a check on divorce, while it assured the wife a living in case divorce occurred.

World’s Oldest Prenuptial Agreement? — 4,000-Year-Old Assyrian Document That Says Husband Can Take a Slave If Wife Is Infertile

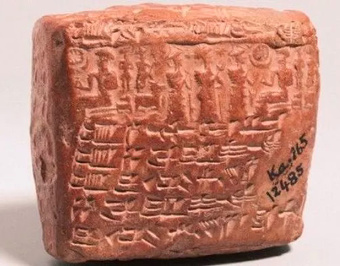

A 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablet outlines an agreement which says it is okay for a husband to take a slave if his wife doesn’t bear any children within a designated period of time. According to researchers that studied the document, tablet is recorded history's very first mention of infertility and arguably the first prenuptial agreement. [Source: Kastalia Medrano, Newsweek, November 10, 2017]

According to the Daily Sabah, a collaboration of Turkish archaeologists from different universities, led by Şanlıurfa's Harran University, discovered the ancient clay tablet in Kültepe, a district within the central Kayseri province. It stated that in the event of failure to conceive within the first two years of marriage, the husband would "hire" a hierodule, or female slave surrogate. The wife, it explained, would "allow" this. A paper detailing the discovery was published in the medical journal Gynecological Endocrinology.

Newsweek reported: Hierodule, depending on the situation, is variously translated as surrogate, slave, prostitute or some combination thereof. Likewise, they may be described as being 'married' to the husband, but the implications—sexual slavery—are nonetheless the same. Their 'function,' in terms of how they were used by other human beings, specific to situations like the one described in the tablet, made for an odd catch-and-release kind of slavery. "The female slave would be freed after giving birth to the first male baby and ensuring that the family is not be left without a child," professor Ahmet Berkız Turp from Harran University's Gynecology and Obstetrics Department told Turkish news channel NTV, according to the Daily Sabah.

Image Sources: Daily Sabah

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024